- •Contents

- •Foreword

- •How to use this book

- •Advisory boards

- •Contributing writers

- •Contributing illustrators

- •What is an insect?

- •Evolution and systematics

- •Structure and function

- •Life history and reproduction

- •Ecology

- •Distribution and biogeography

- •Behavior

- •Social insects

- •Insects and humans

- •Conservation

- •Protura

- •Species accounts

- •Collembola

- •Species accounts

- •Diplura

- •Species accounts

- •Microcoryphia

- •Species accounts

- •Thysanura

- •Species accounts

- •Ephemeroptera

- •Species accounts

- •Odonata

- •Species accounts

- •Plecoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Blattodea

- •Species accounts

- •Isoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mantodea

- •Species accounts

- •Grylloblattodea

- •Species accounts

- •Dermaptera

- •Species accounts

- •Orthoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mantophasmatodea

- •Phasmida

- •Species accounts

- •Embioptera

- •Species accounts

- •Zoraptera

- •Species accounts

- •Psocoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Phthiraptera

- •Species accounts

- •Hemiptera

- •Species accounts

- •Thysanoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Megaloptera

- •Species accounts

- •Raphidioptera

- •Species accounts

- •Neuroptera

- •Species accounts

- •Coleoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Strepsiptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mecoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Siphonaptera

- •Species accounts

- •Diptera

- •Species accounts

- •Trichoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Lepidoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Hymenoptera

- •Species accounts

- •For further reading

- •Organizations

- •Contributors to the first edition

- •Glossary

- •Insects family list

- •A brief geologic history of animal life

- •Index

Order: Isoptera |

Vol. 3: Insects |

Species accounts

West Indian powderpost drywood termite

Cryptotermes brevis

FAMILY

Kalotermitidae

TAXONOMY

Termes brevis Walker, 1853, Jamaica.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Furniture termite.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Alates medium size, 0.4–0.5 in (10–12 mm) from head to tip of wings; median vein curving forward to meet anterior margin in outer one-third of wing; yellow brown. Soldiers have distinctive phragmotic (pluglike), deeply wrinkled head with high frontal flange; short mandibles.

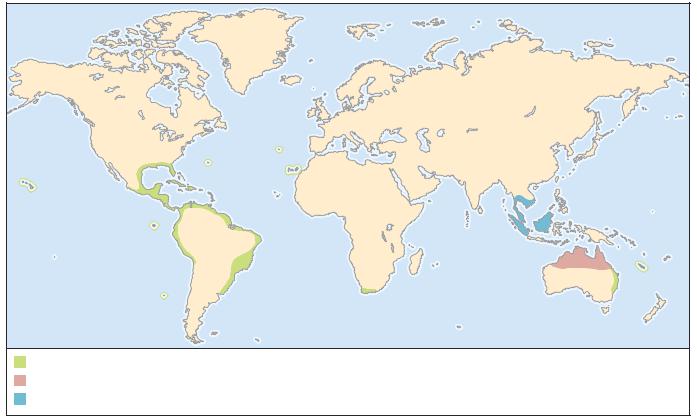

DISTRIBUTION

The most widespread termite species. Regarded as a “tramp” species because easily spread in any item of wood furniture, in the wooden spars, masts, and planking of ships, in wooden pallets, and dunnage (packing material in ships). Native to the West Indies, widely distributed on wood sailing ships after discovery of New World. Now established in most oceanic archipelagos, including the Canary Islands, New Caledonia, the Hawaiian Islands, Bermuda, the Azores, Brazil, Australia, South

Africa, and most of the Gulf Coast cities of the United States, especially peninsular Florida.

HABITAT

Usually found in urban areas in structural timbers of houses, in furniture, and in boats. Rarely occurs in natural settings, prefers drier wood found in human habitation. Also requires humid air and is usually only found in coastal and island localities.

BEHAVIOR

Colonies typically small with only a few thousand individuals, but infested structures may have numerous colonies. Each colony occupies galleries extending a few meters in length. Fecal pellets distinctively shaped, short, six-sided cylinders. Infestation usually detected by piles of fecal pellets which termites dump out of galleries through small round “kick holes” quickly sealed with fecal plaster.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Xylophagous, survives in variety of woods, particularly sound hardwood and softwood timbers, needs very dry and sound wood.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Colonies pro-eusocial, headed by primary reproductives or secondary neotenic replacement reproductives. Neotenic reproductives develop quickly when primaries are removed and engage in lethal fighting until single reproductive pair is

Cryptotermes brevis

Mastotermes darwiniensis

Macrotermes carbonarius

170 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects

reestablished. In Florida, alates fly between dusk and dawn from April to June. After short dispersal flight, wings are broken off and pairs search for holes and crevices in which to form copularium. Mating does not occur until pair seal themselves in.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened; expanding and prospering due to human activity.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Destructive pest of human-made wooden structures, particularly houses and historical buildings. Sometimes referred to as the furniture termite because of its unusual ability to form colonies in relatively small, moveable, wooden items and furnishings. Also known to attack books and archived documents.

Giant Sonoran drywood termite

Pterotermes occidentis

FAMILY

Kalotermitidae

TAXONOMY

Termes occidentis Walker, 1853, Baja California, Mexico.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Large, alates 0.7–0.78 in (18–20 mm) from head to wing tips; antennae with 20 or 21 segments, reddish brown. Soldiers heavy bodied, 0.5–0.6 in (14–15 mm); toothed mandibles, round heads with black compound eyes, broad pronotum, thorax with wing pads, brilliant orange and yellow. Pseudergates large with large compound eyes.

DISTRIBUTION

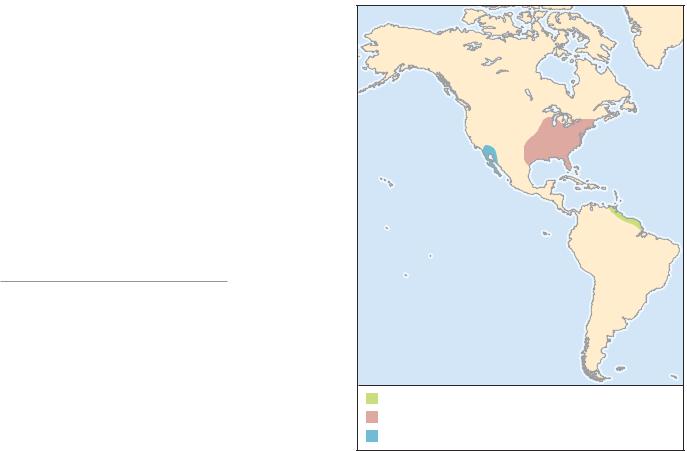

Sonoran Desert, including Baja California and Sonora, Mexico, and southwestern Arizona, United States.

HABITAT

Dead standing branches of paloverde trees of the genus

Cercidium.

BEHAVIOR

Colonies pro-eusocial, rarely exceed 3,000 individuals; most mature colonies have standing population of 1,000 to 1,500. All individuals develop as nymphs. About 5% of nymphs have wing pad scars resulting in development as pseudergates, comprising about 10 to 15% of population. Pseudergates may molt to presoldiers and then to soldiers. Soldiers comprise about 2% of population, guard breaches of the galleries. Nymphs molt to alates in July, small numbers fly from nest at night over flight season from late July through September. Dispersal flights last at least four minutes but not more than one hour. Alates seek beetle emergence holes on dead paloverde trees, which male and female pairs enter and seal off copularium. Primary reproductives always bite off the distal halves of their antenna for reasons that remain unknown.

Order: Isoptera

Termes fatalis

Reticulitermes flavipes

Pterotermes occidentis

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Xylophagous; colonies excavate wide, meandering galleries inside dead paloverde branches. Occasionally found in saguaro cactus skeletons.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Most colonies headed by pair of primary reproductives. However, if one or both are removed, pseudergates start to molt within weeks to become replacement reproductives. When excess numbers molt following death of primaries, lethal fighting follows among neotenic replacements until one male and one female reproductive again become established and suppress, presumably by inhibitory pheromones, further neotenic molting.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened. Critical habitat (dead standing branches of paloverde trees) not utilized by humans except sometimes as firewood. However, as the species is monophagous on one tree species and standing branches on tree are limited, could be subject to local extirpation if intensively collected near urban areas.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Excellent study organism because of large size and ease of maintenance; one of the most well-studied North American drywood termites. Not a pest; no known economic value.

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

171 |

Order: Isoptera

Giant Australian termite

Mastotermes darwiniensis

FAMILY

Mastotermitidae

TAXONOMY

Mastotermes darwiniensis Froggatt, 1896, Port Darwin, West Australia.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Large: alates up to 1.4 in (35 mm) with wings, 2 in (50 mm) wingspan; soldiers 0.45–0.5 in (11.5–13 mm); workers 0.4 in–0.45 in (10–11.5 mm). Only termite whose winged alates possess anal lobe in hind wing; tarsi have five segments, females have short blattoidlike ovipositor with ventral valves, long enough to overlap the dorsal valves; eggs laid in ootheca. Soldiers have round reddish heads with relatively stout short mandibles, long apical teeth; right mandible has two welldefined marginal teeth, but in left mandible only first marginal tooth is well defined, second and third are indistinct. Soldiers and workers have unique coxal armature, or flange, on front legs, and rows of small opposable teeth on femora and tibia, unique leg characters in this family.

DISTRIBUTION

Once cosmopolitan (as indicated by fossils), now confined to tropical northern Australia and nearby islands.

HABITAT

Xylophagous and subterranean, feeds on logs, dead standing trees, and surface wood. Also known to girdle live trees, including commercial tree plantings, then feed on killed trees.

BEHAVIOR

Meso-eusocial. Little is known aside from feeding ecology and reproductive biology.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Independently evolved subterranean foraging habits and ability to build mud shelter tubes to access wood above ground level. Simple nest chambers of several tiers of thin-walled carton cells usually in bole of tree or stump, near or below ground level. Colonies may exceed 1 million individuals and forage over 328 ft (100 m).

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Workers frequently transform into ergatoid reproductives that replace primary reproductives when colonies are orphaned, but more typically develop as supplementary reproductives and form new colonies by budding off from parent colonies. Most reproduction probably by neotenic ergatoid reproductives.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Of phylogenetic interest because of status as a monotypic family, exhibits unique morphological characters that place it as most basal termite and possibly most basal extant species of Dictyopterid. Serious structural, forest, and agricultural pest; most destructive termite in tropical northern Australia; damaging timber in buildings, bridges, poles, fence posts, railway sleepers, living trees, and crops. Also feeds on many host tree species, including live trees, and attacks plantations and crops

Vol. 3: Insects

such as sugar cane. However, its large body, large colony size, and wide diet make it an excellent candidate for beneficial termiticulture on cellulosic wastes.

Eastern subterranean termite

Reticulitermes flavipes

FAMILY

Rhinotermitidae

TAXONOMY

Termes flavipes Kollar, 1837, Vienna, Austria (where it was introduced).

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Alates small, 0.4 in (10 mm) from head to wing tips; black except for yellow tibiae. Soldiers with elongate, parallel-sided, subrectangular, yellow heads, and stout, black, toothless mandibles, strongly curved inward at tips. Top of soldier head with minute opening of frontal gland, or fontanelle. Workers about 0.2 in (6 mm) long; creamy white.

DISTRIBUTION

Native to eastern forests of United States from Florida to Maine, and in the west from Texas to Minnesota; introduced into Canada in southern Ontario, including the Toronto area.

HABITAT

Deciduous hardwood forests.

BEHAVIOR

Colonies are meso-eusocial and forage through shallow, narrow tunnels in soil that connect dead wood items, including stumps, logs, and roots. Also forages up trees on dead limbs and into rotten boles of trees with heart rot or butt rot. In urban environment, feeds on wood landscaping items such as fence posts, edging boards, firewood piles, wood-chip mulch, scrap lumber, and flower planter boxes. Once established in these items, explores foundation cracks and crevices and often finds access to structural wood framing, recruiting more workers and establishing numerous access points into the structure. Since feeding is from inside and most wood framing is concealed, may cause extensive damage over many years before being discovered.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Xylophagous, consumes hardwoods and softwoods, prefers sapwood to heartwood. Preferentially feeds on more porous spring wood of annual rings, leaving harder summer wood, thus damaged wood may have laminated appearance. Consumes both sound wood and partially decayed wood. Galleries often have small parchmentlike partitions of fecal paste and light tan specks of fecal plastering. When working above ground, in structures, or when foraging up trees, builds protective shelter tubes of fine soil particles and saliva, lined with fecal plaster. Shelter tubes are the most conspicuous sign of presence and activity, as no fecal pellets are produced.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

No definitive nest, establishes reproductive chambers in logs, stumps, or other large moist wood items. Since structural wood is usually dry, reproduction rarely occurs in structural timbers. Moves deeper into ground in winter, staying beneath frost line,

172 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects

probably occupying roots of old stumps. Generates large number of nymphoid neotenics from nymphs, which serve as supplementary reproductives and allow seeding of all potential reproductive resources within foraging territory with reproductives; thus, colonies expand continuously as resources are colonized. Most reproduction is by supplementary reproductives. Older colonies have no central nest or foraging territory headed by single primary or replacement pair, but instead extensive, loosely connected gallery systems with an extended family structure. Foraging territories are discovered, exploited to exhaustion, then abandoned as new foraging areas are expanded. This foraging-reproductive strategy is appropriate and well adapted, matched to the pattern of wood production and dispersion in the temperate zone.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened despite intensive control efforts.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Major subterranean termite pest in eastern North America. Responsible for hundreds of millions of dollars of damage and control annually; this damage and collateral expenses of inspection, control, and renovation make it one of the most destructive urban insect pests.

Black macrotermes

Macrotermes carbonarius

FAMILY

Termitidae

TAXONOMY

Termes carbonarius Hagen, 1858, Malay Peninsula.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Very large (largest in Southeast Asia); alates about 1.2 in (30 mm) from head to wing tips, wing span at least 2 in (50 mm). As suggested by species name carbonarius, workers and soldiers very dark, nearly black, a feature often found in free-foraging termites exposed to sunlight. Workers dimorphic, males larger than females. Soldiers also dimorphic but all females; with fleshy lobe at end of labrum; subrectangular heads; razor sharp, saberlike mandibles.

DISTRIBUTION

Southeast Asia, including Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Borneo.

HABITAT

Occurs in flat lowlands, uncommon in hilly terrain. Found in plantations such as rubber, coconut, durian, and teak, especially common in coastal dipterocarp forests.

BEHAVIOR

Colonies are ultra-eusocial. Builds large mounds up to 13 ft (4 m) high and 16 ft (5 m) wide at base. Fungus combs usually in large chambers around periphery of mound. Minor workers specialized for nest work, including tending king and queen, feeding larvae and nymphs, and nest repair. Major workers mainly forage.

Order: Isoptera

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Gramivorous, eating mainly dead grass, twigs, and surface debris cut into short pieces. Only species of subfamily Macrotermitinae to forage above ground; usually at night. Foraging parties involve major and minor soldiers and major workers, but not minor workers. Foraging area changes daily. After opening foraging hole, major workers build pavement trackways to foraging area. More workers then join, fanning out to collect dead grass and twigs; continuous cordon of major and minor soldiers guards outskirts of foraging area. Collected forage is carried below ground and passed to minor workers, who chew it and pass it rapidly through their digestive tract as “primary” feces, then deposit it on fungus comb upon which species of basidiomycete fungus (genus Termitomyces) grow.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Colonies usually headed by royal pair in thick-walled royal cell. Queen’s abdomen unfolds and expands to gross dimensions (physogastry). Subfamily cannot produce neotenic reproductives; when primary reproductives die, colony may also die unless alates are there as replacements.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Plantation pest. Alates sometimes harvested and eaten or used as chicken feed.

Black-headed nasute termite

Nasutitermes nigriceps

FAMILY

Termitidae

TAXONOMY

Termes nigriceps Haldeman, 1858, western Mexico.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Haldeman’s black nasute

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Queen physogastric; rusty yellow except for costal margins of wing scales which are dark brown, 0.7 in (18.5 mm) without wings. Soldiers with very dark heads; nasus wide and dark reddish; dense erect setae over head capsule. Workers dimorphic, rectangular heads; darkly pigmented.

DISTRIBUTION

Widely distributed from western Mexico as far north as Mazatlan, south to Panama and northern South America.

HABITAT

Coastal plains from sea level to about 3,280 ft (1,000 m).

BEHAVIOR

Colonies are meta-eusocial. Builds large conspicuous arboreal carton nests in trees, on fence posts and poles. May have more than one nest per colony.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Xylophagous; feeds mainly above ground via an extensive network of wide shelter tubes attached usually to the lower sides of tree branches.

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

173 |

Order: Isoptera

Zootermopsis laticeps

Nasutitermes nigriceps

Vol. 3: Insects

HABITAT

Rainforest.

BEHAVIOR

Colonies are meta-eusocial. Soldiers capable of violently snapping their mandibles, forcing them to cross downward, pushing the pointed head upward into ceiling of tunnel or nest chamber opening. Presumed function of snapping behavior is to lock soldiers’ head into tunnel to block the advance of predators such as ants or other termites. Species of the subfamily Termitinae often build short, turretlike nests of hard dark fecal material. Nests composed of numerous interconnected cells. Little known about nesting behavior, but some species in

the subfamily build nests inside mounds and nests of other termites.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Humivorous. Large apical teeth and molar without grinding ridges suggest diet of very soft decayed wood or humus.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Nothing known.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Nothing known.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

First species of termite formally named by Linnaeus in 1758, thus has taxonomic significance as ordinal type.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Colonies headed by primary reproductives.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Occasional structural pest.

Linnaeus’s snapping termite

Termes fatalis

FAMILY

Termitidae

TAXONOMY

Termes fatalis Linnaeus, 1758, Para-Maribo, Suriname.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Small, alate about 0.3 in (8.5 mm) with wings; brown, with large apical teeth. Soldiers monomorphic, with pale yellow, elongate, parallel-sided heads with hornlike tubercle projecting forward. Mandibles slender, elongate and rodlike; apices cupped together. Soldier labrum is narrow and rectangular with short points on anterior corners.

DISTRIBUTION

Northeastern South America, in Guyana, Suriname, Trinidad,

and Amazonia, Brazil.

Wide-headed rottenwood termite

Zootermopsis laticeps

FAMILY

Termopsidae

TAXONOMY

Termopsis laticeps Banks, 1906, Florence and Douglas, Arizona, United States.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Largest and most primitive North American termite. Winged alates 1–1.2 in (26–30 mm) from head to wing tips with wing span 1.8–1.9 in (46–48 mm); antennae with 26 segments; cerci with 5 segments; tarsi with 5 segments; reniform compound eyes, simple eyes or ocelli absent; body dark yellowish. Soldiers up to 0.6–0.9 in (16–23 mm) long with spectacularly long and jaggedly toothed mandibles; flattened heads; widest posteriorly; pronotum with anterior corners pointed; large spines on tibiae. Pseudergates develop from nymphs after wing-pad abscission or wingpad biting. Pseudergates develop different pattern of hair over body and may molt several times, enlarging in size each time and developing large, wide head. Functionally reproductive replacement soldiers sometimes develop in orphaned colonies.

DISTRIBUTION

Central and southeastern Arizona to southern New Mexico, West Texas, United States, and Chihuahua and Sonora, Mexico; within altitudinal range 1,500–5,500 ft (457–1,676 m) above sea level.

HABITAT

Occurs in canyons and river valleys in rotten cores of boles and large branches of living riparian trees such as willow, cotton-

174 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects

wood, sycamore, oak, alder, ash, walnut, hackberry, and other hardwoods. Not recorded from conifers or dead, rotten logs. In the relatively arid region it inhabits, only live trees can provide the moist conditions it requires.

BEHAVIOR

Colonies are pro-eusocial. Gallery excavations extend several feet (meters) with concentric, wandering, open chambers in rotten wood. Excavated central area becomes filled with caked mass of fecal pellets. Galleries typically originate from knot hole plugged with a mass of hard fecal pellets; galleries often damp or wet inside. Soldiers agile, defend openings against ants or other predatory intruders.

Order: Isoptera

or small rot pockets where tree previously damaged by wind or beetles. Most field colonies headed by primary reproductive pairs, but replacement reproductives may develop from pseudergates or nymphs. Functional reproductive soldiers with heads smaller than typical soldiers have also been found as replacement reproductives in field colonies. Colonies rarely exceed 1,000 individuals.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened, but could be affected by agricultural or urban development in riparian habitats.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Mycetoxylophagous, feeding only on rotten hardwoods. Feeding probably helps advance development of heart rot in infested trees.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Alates fly in middle of night from late June through early August. Colonies initiated by alate pairs in tree scars, knot holes,

Attacks live trees and extends rot from dead to live portions of trees, hastening collapse or breakage of trees. However, most attacked tree species are not of economic importance, so not considered a pest. Could be pest in mature orchard crops such as pecan and pistachio, but this has not been reported. Could be used for physiological studies of termites because of large size, but collecting colonies difficult, requiring bucksaws or chainsaws, wedges, and sledgehammers.

Resources

Books

Abe, T., D. E. Bignell and M. Higashi, eds. Termites: Evolution, Sociality, Symbiosis, Ecology. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic, 2000.

Choe, J. C., and B. J. Crespi, eds. The Evolution of Social Behavior in Insects and Arachnids. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Grassé, P.-P. Termitologia, 3 vols. Paris: Masson, 1982–1986.

Kofoid, C. A., et al., eds. Termites and Termite Control.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1934.

Krishna, K., and F. M. Weesner, eds. Biology of Termites, 2 vols. New York: Academic Press, 1969–1970.

Myles, T. G. “Resource Inheritance in Social Evolution from Termites to Man.” In The Ecology of Social Behavior, edited by C. N. Slobodchikoff. New York: Academic Press, 1988.

Sands, W. A. The Identification of Worker Castes of Termite Genera from Soils of Africa and the Middle East. London: CAB International, 1988.

Uys, V. A Guide to the Termite Genera of Southern Africa. Plant Protection Research Handbook No. 15. Pretoria, South Africa: Agricultural Research Council, 2002.

Wilson, E. O. The Insect Societies. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971.

—. Sociobiology: The Abridged Edition. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1980.

Periodicals

Myles, T. G. “Evidence of Parental and/or Sibling Manipulation in Three Species of Termites in Hawaii.”

Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society 27 (1986): 129–136.

—.“Reproductive Soldiers in the Termopsidae (Isoptera).”

Pan-Pacific Entomologist 62, no. 4 (1986): 293–299.

—.“Review of Secondary Reproduction in Termites (Insecta: Isoptera) with Comments on Its Role in Termite Ecology and Social Evolution.” Sociobiology 33 (1999): 1–91.

—.“Termite Eusocial Evolution: A Re-Examination of Bartz’s Hypothesis and Assumptions.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 63 (1988): 1–23.

Timothy George Myles, PhD

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

175 |

This page intentionally left blank