- •Contents

- •Foreword

- •How to use this book

- •Advisory boards

- •Contributing writers

- •Contributing illustrators

- •What is an insect?

- •Evolution and systematics

- •Structure and function

- •Life history and reproduction

- •Ecology

- •Distribution and biogeography

- •Behavior

- •Social insects

- •Insects and humans

- •Conservation

- •Protura

- •Species accounts

- •Collembola

- •Species accounts

- •Diplura

- •Species accounts

- •Microcoryphia

- •Species accounts

- •Thysanura

- •Species accounts

- •Ephemeroptera

- •Species accounts

- •Odonata

- •Species accounts

- •Plecoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Blattodea

- •Species accounts

- •Isoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mantodea

- •Species accounts

- •Grylloblattodea

- •Species accounts

- •Dermaptera

- •Species accounts

- •Orthoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mantophasmatodea

- •Phasmida

- •Species accounts

- •Embioptera

- •Species accounts

- •Zoraptera

- •Species accounts

- •Psocoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Phthiraptera

- •Species accounts

- •Hemiptera

- •Species accounts

- •Thysanoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Megaloptera

- •Species accounts

- •Raphidioptera

- •Species accounts

- •Neuroptera

- •Species accounts

- •Coleoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Strepsiptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mecoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Siphonaptera

- •Species accounts

- •Diptera

- •Species accounts

- •Trichoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Lepidoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Hymenoptera

- •Species accounts

- •For further reading

- •Organizations

- •Contributors to the first edition

- •Glossary

- •Insects family list

- •A brief geologic history of animal life

- •Index

Vol. 3: Insects |

Order: Coleoptera |

Species accounts

Giraffe-necked weevil

Trachelophorus giraffa

FAMILY

Attelabidae

TAXONOMY

Aploderus (Trachelophorus) giraffa Jekel, 1860, “Madagascar.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Red-and-black giraffe beetle; French: Scarabée girafe; Dutch: Giraf nek kever; German: Giraffenrüssler.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Males up to 0.98 in (2.5 cm). Black with red elytra; only males have long “neck.”

DISTRIBUTION

Madagascar.

HABITAT

Forests.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

None known.

Giant metallic ceiba borer

Euchroma gigantea

FAMILY

Buprestidae

TAXONOMY

Buprestis gigantea Linnaeus, 1758, “America.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

Spanish: Eucroma, catzo; Portuguese: Mae do sol, ôlho do sol.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Grows to 2–2.8 in (5–7 cm). Wrinkled elytra, shining green infused with red. Back of prothorax has two large black spots. Freshly emerged specimens covered with yellow bloom.

BEHAVIOR

Sits on leaves in open areas and along roadsides; rolls leaves.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Feeds on the leaves of Dichaetanthera cordifolia, a small tree in the family Melastomataceae.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Females lay their eggs on leaves; the leaves are rolled up into a tube to protect and nourish the larvae.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

Scarabaeus sacer

Lytta vesicatoria

Trachelophorus giraffa

Alaus oculatus

Ulochaetes leoninus

Euchroma gigantea

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

327 |

Order: Coleoptera

Priacma serrata

Zopherus chilensis

Dineutus discolor

DISTRIBUTION

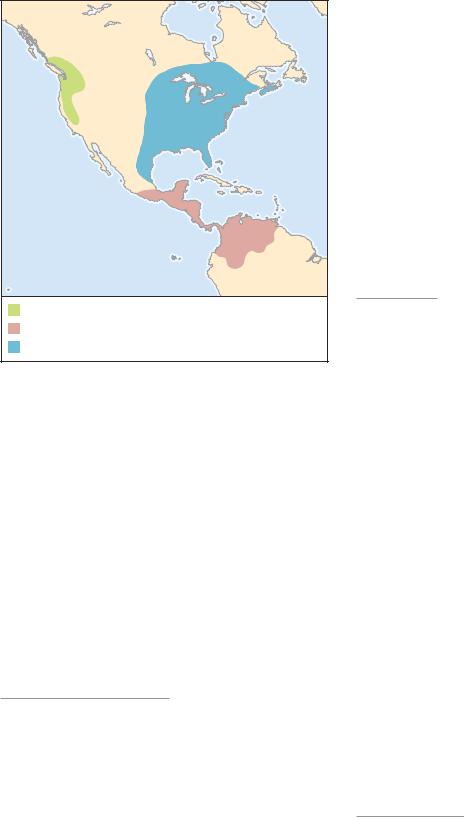

Mexico to Argentina and the Antilles.

HABITAT

Tropical forests.

BEHAVIOR

Common on trunks of living or dead bombacaceous trees.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Larvae bore through trunks of dead bombacaceous trees.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Nothing is known.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Elytra are made into jewelry and ornaments by peoples in Central and South America; adults are eaten by Tzeltal-Mayan Indians in Chiapas, Mexico.

Titanic longhorn beetle

Titanus gigantea

FAMILY

Cerambycidae

TAXONOMY

Titanus gigantea Linnaeus, 1758, “Cayania.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Grows up to 6.7 in (17 cm). Dark brown to black with faint, powerful mandibles and longitudinal ridges on the elytra.

Vol. 3: Insects

DISTRIBUTION

Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, French Guiana, and northern Brazil.

HABITAT

Tropical forests.

BEHAVIOR

Adults are attracted to lights at night.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Larvae probably feed in rotten wood.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Nothing is known.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

One of the world’s largest beetles, specimens are highly prized and sell for hundreds of dollars.

Lion beetle

Ulochaetes leoninus

FAMILY

Cerambycidae

TAXONOMY

Ulochaetes leoninus LeConte, 1854, “Prairie Pass, Oregon Territory.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Grows to 0.67–0.98 in (17–25 mm); hairy with black and yellow markings and short elytra.

DISTRIBUTION

Pacific coast, from British Columbia to southern California.

HABITAT

Pine forests.

BEHAVIOR

Look, sound, and behave like bumble bees.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Larvae bore into sapwood of conifers.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Eggs are laid at the base of standing dead trees and stumps.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Interesting example of physical and behavioral mimicry.

Cupedid beetle

Priacma serrata

FAMILY

Cupedidae

328 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects

TAXONOMY

Cupes serrata LeConte, 1861, “East of Fort Colville,” Oregon.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: cupesid beetle.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Reaches 0.4–0.9 in (11–22 mm). Irregularly marked with grayishblack scales; elytra with square pits.

DISTRIBUTION

Western North America.

HABITAT

Under tree bark in coniferous forests.

BEHAVIOR

During daylight hours, males sometimes are attracted to sheets freshly laundered with bleach.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Probably feed on fungus in rotten wood.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Nothing is known.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

A primitive family of beetles similar in appearance to the extinct Tshekardoleidae.

Great water beetle

Dytiscus marginalis

FAMILY

Dytiscidae

TAXONOMY

Dytiscus marginalis Linné, 1758, “Europae.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Great water diving beetle.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Grows up to 1.4 in (35 mm). Prothorax and elytra have pale borders; male’s elytra is smooth and female’s usually grooved.

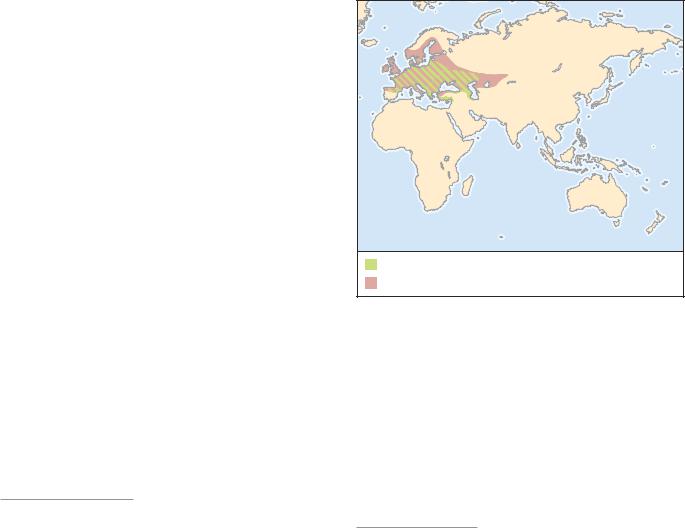

DISTRIBUTION

Europe.

HABITAT

Lakes and ponds with muddy bottoms.

BEHAVIOR

Obtains oxygen by breaking the water surface with the tip of the abdomen and trapping a bubble under the elytra.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Preys on aquatic insects, mollusks, crustaceans, and even tadpoles and small fish.

Order: Coleoptera

Lucanus cer vus

Dytiscus marginalis

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Eggs are deposited singly on stems of aquatic plants. Larvae molt three times in 35–40 days; pupation takes place in damp ground next to water. One generation per year

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

One of the largest and most intensely studied European water beetles.

Eyed click beetle

Alaus oculatus

FAMILY

Elateridae

TAXONOMY

Elater oculatus Linné, 1758, “America septentrionalis.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Grows to 0.98–1.96 in (25–50 mm). Pronotum with two black spots encircled with white scales.

DISTRIBUTION

Eastern North America.

HABITAT

Woodlands.

BEHAVIOR

Adults found on hardwoods or under bark.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Larvae live in rotten hardwood. Adults and larvae feed on the larvae of wood-boring beetles.

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

329 |

Order: Coleoptera

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Nothing is known.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

None known.

Whirligig beetle

Dineutus discolor

FAMILY

Gyrinidae

TAXONOMY

Dineutus discolor Aube, 1838, “États-Unis d’Amerique.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Gyrinids, apple bugs.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Reaches 0.4–0.5 in (11–13 mm). Black and shining, with pale underside.

DISTRIBUTION

Eastern North America and Mexico.

HABITAT

Surface of slow-moving ponds and streams.

BEHAVIOR

Lives singly or in groups.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Preys on insects trapped on the water surface.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Eggs are laid on submerged plants. Aquatic larvae prey on small invertebrates. Pupate in moist soil near water. Adults overwinter in debris at the edge of water.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

None known.

Pink glowworm

Microphotus angustus

FAMILY

Lampyridae

TAXONOMY

Microphotus angustus LeConte, 1874, “Mariposa, California.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Males reach 0.2 in (6 mm) and females 0.4–0.5 in (11–13 mm). Pink females are larviform; males look like fireflies with large eyes.

Vol. 3: Insects

Dynastes hercules

Microphotus angustus

DISTRIBUTION

California and Oregon.

HABITAT

Forests and moist canyons in chaparral.

BEHAVIOR

Females hang with their heads pointed upward on rocks and stumps and “call” with continuous light. Males seldom are seen and flash weakly only when disturbed.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Unknown; larvae probably prey on small invertebrates.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Nothing is known.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

None known.

European stag beetle

Lucanus cervus

FAMILY

Lucanidae

TAXONOMY

Scarabaeus cervus Linnaeus, 1758, “Europae.”

330 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects

OTHER COMMON NAMES

German: Donnerkafer, Hausbrenner, Feueranzunder, Köhler,

Feuerschröter.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Males reach 1.4–2.95 in (35–75 mm) and females 1.2–1.8 in (30–45 mm). Dark brownish–black beetle. The male has a broad head and antler-like mandibles; female is smaller and more stout, with relatively small mandibles.

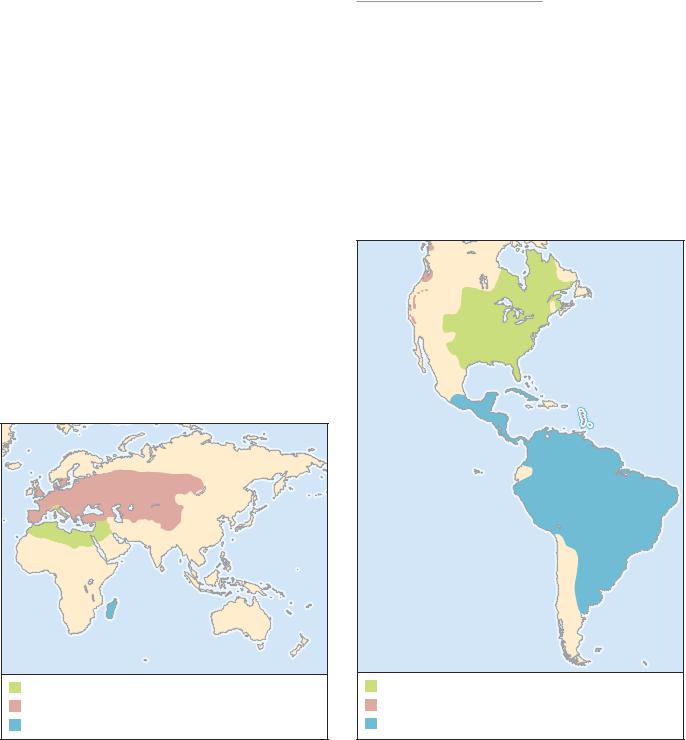

DISTRIBUTION

Central, southern, and western Europe; Asia Minor; Syria.

HABITAT

Old oak forests.

BEHAVIOR

Males use mandibles against rival males over females.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Adults feed on sap; larvae eat rotting wood.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Eggs are laid in old wood, larva take three to five years to mature. Adult matures in autumn but overwinters in pupal case.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Collection of this species is forbidden in several European countries.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Historically a symbol of evil and bad luck.

Spanish fly

Lytta vesicatoria

FAMILY

Meloidae

TAXONOMY

Meloe vesicatoria Linné, 1758. Type locality not specified.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Reaches 0.5–0.9 in (12–22 mm); slender, soft-bodied metallic golden-green beetle.

DISTRIBUTION

Throughout southern Europe and eastward to Central Asia and Siberia.

HABITAT

Scrublands and woods.

BEHAVIOR

When disturbed, meloids release the blistering agent cantharidin from their leg joints.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Adults feed on leaves of ash, lilac, amur privet, and white willow trees; larvae are parasitic on the brood of ground nesting bees.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Develop by hypermetamorphosis, a type of complete metamorphosis in which first larval instar (the triungulin) is very active,

Order: Coleoptera

while remaining instars are more sedentary and grublike. Eggs are laid near the entrance of host bee’s nest; triungulins crawl into nest on their own.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Bodies are filled with the toxin cantharidin; elytra were once pulverized and marketed as an aphrodisiac as well as a cure for various ailments.

Hercules beetle

Dynastes hercules

FAMILY

Scarabaeidae

TAXONOMY

Scarabaeus hercules Linné, 1758, “America.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

French: Scieurs de long; Spanish: Tijeras.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Males reach 5.9–6.7 in (15–17 cm), up to half of which corresponds to the thoracic horn.

DISTRIBUTION

Mexico, Central and northern South America, Guadeloupe, and the Dominican Republic.

HABITAT

Humid tropical forests.

BEHAVIOR

Adults are attracted to oozing sap and sweet fruits; larvae develop in rotten logs.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Nocturnal and frequently attracted to lights.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Males defend feeding sights that will attract females; horns of males are used to grapple with other males over females.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Ingesting the horn is thought by some people to increase their sexual potency.

Sacred scarab

Scarabaeus sacer

FAMILY

Scarabaeidae

TAXONOMY

Scarabaeus sacer Linné, 1758, “Aegypto.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

331 |

Order: Coleoptera

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Grows to 0.98–1.2 in (25–30 mm). Black, with rakelike head and forelegs.

DISTRIBUTION

Mediterranean region and central Europe.

HABITAT

Steppe, forest-steppe, and semi-desert.

BEHAVIOR

Adults track dung by smell as food for themselves and their offspring. The female stands head down and rolls a dung ball with the second and third pairs of legs; ball is buried as food for larva.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Adults use membranous mandibles to strain fluids, molds, and other suspended particles as food from dung; larvae eat solid dung.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Single humpbacked larva feeds and pupates inside buried dung ball.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Symbol of the ancient Egyptian sun god Ra. Scarab jewelry is worn today as a good luck charm. Significant recyclers of animal waste.

Vol. 3: Insects

American burying beetle

Nicrophorus americanus

FAMILY

Silphidae

TAXONOMY

Nicrophorus americanus Olivier, 1790, “Amérique septentrionale.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Reaches 0.8–1.4 in (20–35 mm). Black, with orange antennal club. Head and pronotum have central orange spot; and elytra have four wide spots.

DISTRIBUTION

Formerly throughout eastern North America; restricted now to isolated populations in the Midwest, with populations reintroduced to Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

HABITAT

Woodlands, grassland prairies, forest edge, and scrubland.

BEHAVIOR

Provides parental care for its young.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Scavenges and buries carrion.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Mating pair prepares carrion as food for themselves and their larvae.

Ocypus olens

Nicrophorus americanus Titanus gigantea

332 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects

CONSERVATION STATUS

Listed as Endangered by IUCN and by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Symbolic of habitat destruction and modification throughout eastern North America.

Devil’s coach-horse

Ocypus olens

FAMILY

Staphylinidae

TAXONOMY

Staphylinus olens Müller, 1764. Type locality not specified.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Rove beetle.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Grows to 0.9–1.3 in (22–33 mm). Black, with short elytra exposing abdominal segments.

DISTRIBUTION

Lower elevations of Europe, Russia, Turkey, North Africa, and the Canary Islands; established in parts of North America.

HABITAT

Under stones, damp leaves, and moss.

BEHAVIOR

When alarmed, the beetle spreads its powerful jaws and curls its abdomen over its back to emit a foul-smelling brown fluid.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Adults and larvae prey on soil-dwelling invertebrates.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Nothing is known.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

Order: Coleoptera

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Once a symbol of evil associated with death.

Ma’kech

Zopherus chilensis

FAMILY

Zopheridae

TAXONOMY

Zophorus [sic] chilensis Gray, 1832. Type locality not specified.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Jeweled beetle.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Grows to 1.3–1.6 in (34–40 mm). Extremely hard exoskeleton; rough back is white with irregular black blotches.

DISTRIBUTION

Southern Mexico to Venezuela and Colombia.

HABITAT

Found on bark of dead trees.

BEHAVIOR

When disturbed, adults tuck in their legs and play dead.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Larvae presumably feed on fungal hyphae in rotten wood; adults eat cereals in captivity.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Nothing is known.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Living beetles are adorned with beads, tethered with a gold chain, and worn as living costume jewelry as traditional reminder of an ancient Yucatecan legend.

Resources

Books

Arnett, Ross H., Jr., and Michael C. Thomas, eds. American Beetles. Vol. 1, Archostemata, Myxophaga, Adephaga, Polyphaga: Staphyliniformia. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2001.

Arnett, Ross H., Jr., Michael C. Thomas, Paul E. Skelley, and J. Howard Frank, eds. American Beetles. Vol. 2, Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionidae. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 2002.

Crawford, C. S. Biology of Desert Invertebrates. Berlin: SpringerVerlag, 1981.

Crowson, R. A. The Biology of the Coleoptera. London: Academic Press, 1981.

Elias, Scott A. Quaternary Insects and Their Environments.

Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.

Evans, Arthur V., and Charles L. Bellamy. An Inordinate Fondness for Beetles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Evans, Arthur V., and J. N. Hogue. Introduction to California Beetles. Berkeley: University of California Press, in press.

Evans, D. L., and J. O. Schmidt, eds. Insect Defenses: Adaptive Mechanisms and Strategies of Prey and Predators. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990.

Klausnitzer, B. Beetles. New York: Exeter Books, 1983.

Lawrence, J. F., and E. B. Britton. Australian Beetles. Carlton, Australia: Melbourne University Press, 1994.

Lawrence, J. F., and A. F. Newton, Jr. “Families and Subfamilies of Coleoptera (with Selected Genera, Notes, References and Data on Family-Group Names).” In Biology, Phylogeny, and Classification of Coleoptera. Papers Celebrating

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

333 |

Order: Coleoptera

Resources

the 80th Birthday of Roy A. Crowson, edited by J. Pakaluk and S. A. Slipinski. Warsaw, Poland: Muzeum i Instytut Zoologii PAN, 1995.

Meads, M. Forgotten Fauna: The Rare, Endangered, and Protected Invertebrates of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, 1990.

Pakaluk, J., and S. A. Slipinski, eds. Biology, Phylogeny, and Classification of Coleoptera. Papers Celebrating the 80th Birthday of Roy A. Crowson. Warsaw, Poland: Muzeum i Instytut Zoologii PAN, 1995.

Stehr, Frederick W., ed. Immature Insects. Vol. 2. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1991.

White, R. E. A Field Guide to the Beetles of North America.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983.

Periodicals

Alcock, J. “Postinsemination Associations between Males and Females in Insects: The Mate-Guarding Hypothesis.”

Annual Review of Entomology 39 (1994): 1–21.

Beutel, R. “Über Phylogenese und Evolution der Coleoptera (Insecta), insbesondere der Adephaga.” Abhandlungen des Naturwissenshaftlichen Vereins in Hamburg 31 (1997): 1–164.

Beutel, R., and F. Haas. “Phylogenetic Relationships of the Suborders of Coleoptera (Insecta).” Cladistics 16 (2000): 103–141.

Caterino, M. S., V. L. Shull, P. M. Hammond, and A. P. Vogler. “Basal Relationships of Coleoptera Inferred from 18S rDNA Sequences.” Zoologica Scripta 31 (2002): 41–49.

Eberhard, William G. “Horned Beetles.” Scientific American 242, no. 3 (1980): 166–182.

Emlen, D. J. “Integrating Development with Evolution: A Case Study with Beetle Horns.” Bioscience 50, no. 5 (2000): 403–418.

Farrell, Brian D. “‘Inordinate Fondness’ Explained: Why Are There So Many Beetles?” Science 281 (1998): 555–559.

Vol. 3: Insects

Hadley, N. F. “Beetles Make Their Own Waxy Sunblock.” Natural History 102, no. 8 (1993): 44–45.

Lomolino, Mark V., J. C. Creighton, G. D. Schnell, and D. L. Certain. “Ecology and Conservation of the Endangered American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus).” Conservation Biology 9, no. 3 (1995): 605–614.

McIver, J. D., and G. Stonedahl. “Myrmecomorphy: Morphological and Behavioral Mimicry of Ants.” Annual Review of Entomology 38 (1993): 351–379.

Milne, L. J., and M. J. Milne. “The Social Behavior of Burying Beetles.” Scientific American 235, no. 2 (1976): 84–89.

Murlis, J. “Odor Plumes and How Insects Use Them.” Annual Review of Entomology 37 (1992): 505–532.

Rettenmeyer, C. W. “Insect Mimicry.” Annual Review of Entomology 15 (1970): 43–74.

Other

“The Balfour-Browne Club.” October 1996 [April 14, 2003].

<http://www.lifesci.utexas.edu/faculty/sjasper/beetles/

BBClub.htm>.

“Beetles (Coleoptera) and Coleopterists.” [April 14, 2003].

<http://www.zin.ru/Animalia/Coleoptera/eng>.

“Coleoptera Home Page.” March 28, 2003 [April 14, 2003].

<http://www.coleoptera.org>.

“The Coleopterist.” [April 14, 2003]. <http://www.coleopterist

.org.uk>.

“Coleopterists Society.” [April 14, 2003]. <http://www

.coleopsoc.org>.

“The Japan Coleopterological Society.” [April 14, 2003]. <http://www.mus-nh.city.osaka.jp/shiyake/j-coleopt-soc

.html>.

“Wiener Coleopterologen Verein (Vienna Coleopterists Society).” September 7, 2001 [April 14, 2003]. <http://www

.nhm-wien.ac.at/NHM/2Zoo/coleoptera/wcv_e.html>.

Arthur V. Evans, DSc

334 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |