C7

.pdf

1 ft.

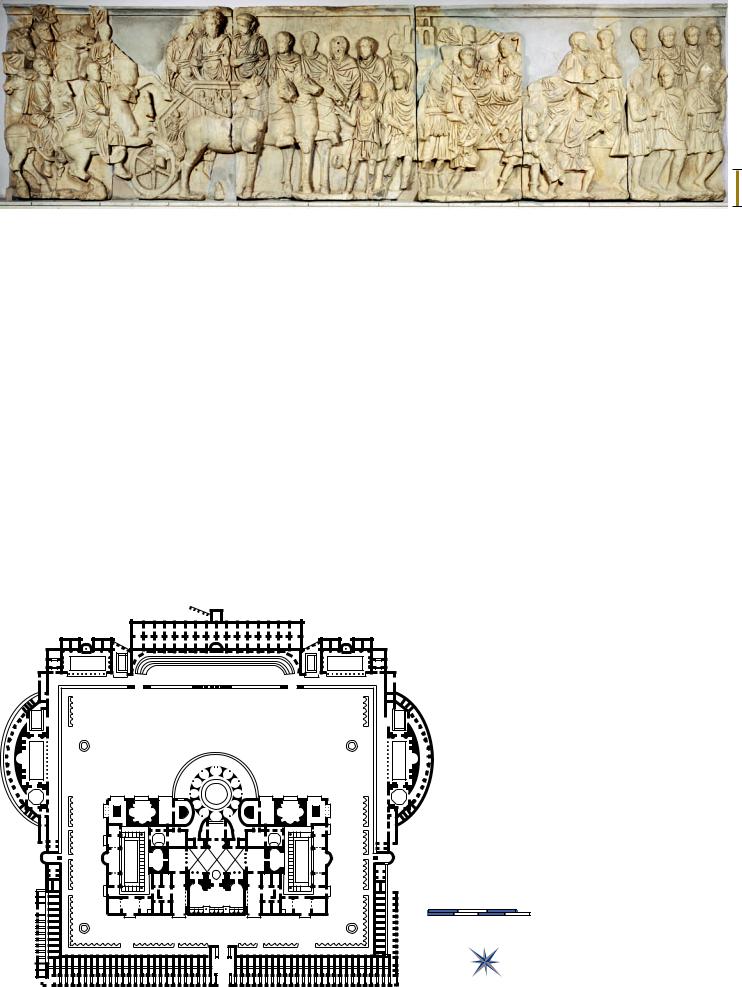

7-65 Chariot procession of Septimius Severus, relief from the attic of the Arch of Septimius Severus, Lepcis Magna, Libya, 203 CE. Marble, 5 6 high. Castle Museum, Tripoli.

A new non-naturalistic aesthetic emerged in later Roman art. In this relief from a triumphal arch, Septimius Severus and his two sons face the viewer even though their chariot is moving to the right.

incisions into the marble surface. More remarkable, however, is the moving characterization of Caracalla’s suspicious nature, a further development from the groundbreaking introspection of the portraits of Marcus Aurelius. Caracalla’s brow is knotted, and he abruptly turns his head over his left shoulder, as if he suspects danger from behind. The emperor had reason to be fearful. An assassin’s dagger felled him in the sixth year of his rule. Assassination would be the fate of many Roman emperors during the turbulent third century CE.

LEPCIS MAGNA The hometown of the Severans was Lepcis Magna, on the coast of what is now Libya. In the late second and early third centuries CE, the Severans constructed a modern harbor there as well as a new forum, basilica, arch, and other monuments. The Arch of Septimius Severus has been rebuilt. It features friezes on the attic on all four sides. One frieze (FIG. 7-65) depicts the chariot procession of the emperor and his two sons on the occasion of their homecoming in 203. Unlike the triumph panel (FIG. 7-41) on the Arch of Titus in Rome, this relief gives no sense of rushing motion. Rather, it has a

stately stillness. The chariot and the horsemen behind it are moving forward, but the emperor and his sons are detached from the procession and face the viewer. Also different is the way the figures in the second row have no connection with the ground and are elevated above the heads of those in the first row so that they can be seen more clearly.

Both the frontality and the floating figures were new to official Roman art in Antonine and Severan times, but both appeared long before in the private art of freed slaves (FIGS. 7-9 and 7-10). Once sculptors in the emperor’s employ embraced these non-Classical elements, they had a long afterlife, largely (although never totally) displacing the Classical style the Romans adopted from Greece. As is often true in the history of art, the emergence of a new aesthetic was a by-product of a period of social, political, and economic upheaval. Art historians call this new non-naturalistic, more abstract style the Late Antique style.

BATHS OF CARACALLA The Severans were also active builders in the capital. The Baths of Caracalla (FIG. 7-66) in Rome were the greatest in a long line of bathing and recreational complexes

7-66 Plan of the Baths of Caracalla, Rome, Italy, 212–216 CE. (1) natatio, (2) frigidarium, (3) tepidarium,

(4) caldarium, (5) palaestra.

Caracalla’s baths could accommodate 1,600 bathers. They resembled a modern health spa and included libraries, lecture halls, and exercise courts in addition to bathing rooms and a swimming pool.

4

3

2

5 |

5 |

1

0 |

100 |

200 |

300 feet |

0 |

50 |

100 meters |

N

Late Empire |

197 |

7-67 Frigidarium, Baths of Diocletian, Rome, ca. 298–306 CE (remodeled by MICHELANGELO as the nave of Santa Maria degli Angeli, 1563).

The groin-vaulted nave of the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Rome was once the frigidarium of the Baths of Diocletian. It gives an idea of the lavish adornment of imperial Roman baths.

erected with imperial funds to win the public’s favor. Made of brickfaced concrete and covered by enormous vaults springing from thick walls up to 140 feet high, Caracalla’s baths dwarfed the typical baths of cities and towns such as Ostia and Pompeii. The design was symmetrical along a central axis, facilitating the Roman custom of taking sequential plunges in warm-, hot-, and cold-water baths in, respectively, the tepidarium, caldarium, and frigidarium. The caldarium (FIG. 7-66, no. 4) was a huge circular chamber with a concrete drum even taller than the Pantheon’s (FIGS. 7-49 to 7-51) and a dome almost as large. Caracalla’s baths also had landscaped gardens, lecture halls, libraries, colonnaded exercise courts (palaestras), and a giant swimming pool (natatio). The entire complex covered an area of almost 50 acres. Archaeologists estimate that up to 1,600 bathers at a time could enjoy this Roman equivalent of a modern health spa. A branch of one of the city’s major aqueducts supplied water, and furnaces circulated hot air through hollow floors and walls throughout the bathing rooms.

The Baths of Caracalla also featured stuccoed vaults, mosaic floors (both black-and-white and polychrome), marble-faced walls, and marble statuary. One statue on display was the 10-foot-tall copy of Lysippos’s Herakles (FIG. 5-66), whose muscular body must have inspired Romans to exercise vigorously. The concrete vaults of the baths collapsed long ago, but visitors can get an excellent idea of what the central bathing hall, the frigidarium, once looked like from the nave (FIG. 7-67) of the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Rome, which was once the frigidarium of the later Baths of Diocle-

198 Chapter 7 T H E RO M A N E M P I R E

tian. The Renaissance interior (remodeled in the 18th century) of that church has, of course, many new elements foreign to a Roman bath, including a painted altarpiece. The ancient mosaics and marble revetment are long gone, but the present-day interior with its rich wall treatment, colossal columns with Composite capitals, immense groin vaults, and clerestory lighting gives a better sense of the character of a Roman imperial bathing complex than does any other building in the world. It takes a powerful imagination to visualize the original appearance of Roman concrete buildings from the woeful ruins of brick-faced walls and fallen vaults at ancient sites today, but Santa Maria degli Angeli makes the task much easier.

The Soldier Emperors

The Severan dynasty ended when Severus Alexander (r. 222–235 CE) was murdered. The next half century was one of almost continuous civil war. One general after another was declared emperor by his troops, only to be murdered by another general a few years or even a few months later. (In 238 CE, two co-emperors the Senate chose were dragged from the imperial palace and murdered in public after only three months in office.) In these unstable times, no emperor could begin ambitious architectural projects. The only significant building activity in Rome during the era of the “soldier emperors” occurred under Aurelian (r. 270–275 CE). He constructed a new defensive wall circuit for the capital—a military necessity and a poignant commentary on the decay of Roman power.

TRAJAN DECIUS If architects went hungry in third-century Rome, sculptors and engravers had much to do. The mint produced great quantities of coins (in debased metal) so that the troops could be paid with money stamped with the current emperor’s portrait and not with that of his predecessor or rival. Each new ruler set up portrait statues and busts everywhere to assert his authority. The sculpted portraits of the third century CE are among the most moving ever made, as notable for their emotional content as they are for their technical virtuosity. Portraits of Trajan Decius (r. 249–251), such as the marble bust illustrated here (FIG. 7-68), show the emperor, who is best known for persecuting Christians, as an old man with bags under his eyes and a sad expression. In his eyes, which glance away nervously rather than engage the viewer directly, is the anxiety of a man who knows he can do little to restore order to an out-of-control world. The sculptor modeled the marble as if it were pliant clay, compressing the sides of the head at the level of the eyes, etching the hair and beard into the stone, and chiseling deep lines in the forehead and around the mouth. The portrait reveals the anguished soul of the man—and of the times.

TREBONIANUS GALLUS Decius’s successor was Trebonianus Gallus (r. 251–253 CE), another short-lived emperor. In a larger- than-life-size bronze portrait (FIG. 7-69), Trebonianus appears in heroic nudity, as had so many emperors and generals before him. His physique is not, however, that of the strong but graceful Greek athletes Augustus and his successors admired so much. Instead, his is a wrestler’s body with massive legs and a swollen trunk. The heavyset body dwarfs his head, with its nervous expression. In this portrait, the Greek ideal of the keen mind in the harmoniously proportioned body gave way to an image of brute force, an image well suited to the age of the soldier emperors.

THIRD-CENTURY SARCOPHAGI By the third century, burial of the dead had become so widespread that even the imperial family was practicing it in place of cremation. Sarcophagi were more popular than ever. An unusually large sarcophagus (FIG. 7-70), discovered in Rome in 1621 and purchased by Cardinal Ludovisi, is

1 in.

7-68 Portrait bust of Trajan Decius, 249–251 CE. Marble, full bust 2 7 high. Musei Capitolini, Rome.

This portrait of a short-lived “soldier emperor” depicts an older man with bags under his eyes and a sad expression. The eyes glance away nervously, reflecting the anxiety of an insecure ruler.

1 ft.

7-69 Heroic portrait of Trebonianus Gallus, from Rome, Italy,

Bronze, 7 11 high. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In this over-life-size heroically nude statue, Trebonianus Gallus projects an image of brute force. He has the massive physique of a powerful wrestler, but his face has a nervous expression.

7-70 Battle of Romans and barbarians (Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus), from Rome, Italy, ca. 250–260 CE. Marble, 5 high.

Museo Nazionale Romano–Palazzo Altemps, Rome.

A chaotic scene of battle between Romans and barbarians decorates the front of this sarcophagus. The sculptor piled up the writhing, emotive figures in an emphatic rejection of Classical perspective.

1 ft.

7-71 Sarcophagus of a philosopher,

ca. 270–280 CE. Marble, 4 11 high. Musei

Vaticani, Rome.

On many third-century sarcophagi, the deceased appears as a learned intellectual. Here, the seated Roman philosopher is the central frontal figure. His two female muses also have portrait features.

1 ft.

decorated on the front with a chaotic scene of battle between Romans and one of their northern foes, probably the Goths. The sculptor spread the writhing and highly emotive figures evenly across the entire relief, with no illusion of space behind them. This piling of figures is an even more extreme rejection of Classical perspective than was the use of floating ground lines on the pedestal of the Column of Antoninus Pius (FIG. 7-58). It underscores the increasing dissatisfaction Late Antique artists felt with the Classical style.

Within this dense mass of intertwined bodies, the central horseman stands out vividly. He wears no helmet and thrusts out his open right hand to demonstrate that he holds no weapon. Several scholars have identified him as one of the sons of Trajan Decius. In an age when the Roman army was far from invincible and Roman emperors were constantly felled by other Romans, the young general on the Ludovisi battle sarcophagus is boasting that he is a fearless commander assured of victory. His self-assurance may stem from his having embraced one of the increasingly popular Oriental mystery religions. On the youth’s forehead is carved the emblem of Mithras, the Persian god of light, truth, and victory over death.

The insecurity of the times led many Romans to seek solace in philosophy. On many third-century sarcophagi, the deceased assumes the role of the learned intellectual. One especially large example (FIG. 7-71) depicts a seated Roman philosopher holding a scroll. Two standing women (also with portrait features) gaze at him from left and right, confirming his importance. In the background are other philosophers, students or colleagues of the central deceased teacher. The two women may be the deceased’s wife and daughter, two sisters, or some other combination of family members. The composition, with a frontal central figure and two subordinate flanking figures, is typical of the Late Antique style. This type of sarcophagus became very popular for Christian burials. Sculptors used the wise-man motif not only to portray the deceased (FIG. 8-6) but also Christ flanked by his apostles (FIG. 8-7).

TEMPLE OF VENUS, BAALBEK The decline in respect for Classical art also can be seen in architecture. At Baalbek (ancient Heliopolis) in present-day Lebanon, the architect of the Temple of Venus (FIG. 7-72), following in the “baroque” tradition of the Treasury at Petra (FIG. 7-53), ignored almost every rule of Classical design. Although made of stone, the third-century building, with its circular domed cella set behind a gabled columnar facade, was in many ways a critique of the concrete Pantheon (FIG. 7-49), which by then had achieved the status of a classic. Many features of the Baalbek temple intentionally depart from the norm. The platform, for example, is scalloped all around the cella. The columns—the only known instance of five-sided Corinthian capitals with corresponding pentagonal bases—support a matching scalloped entablature (which serves to buttress the shallow stone dome). These concave forms and those of the niches in the cella walls play off against the cella’s convex shape. Even the “traditional” facade of the Baalbek temple is eccentric. The unknown architect inserted an arch within the triangular pediment.

Diocletian and the Tetrarchy

In an attempt to restore order to the Roman Empire, Diocletian (r. 284–305 CE), whose troops proclaimed him emperor, decided to share power with his potential rivals. In 293 he established the tetrarchy (rule by four) and adopted the title of Augustus of the East. The other three tetrarchs were a corresponding Augustus of the West, and Eastern and Western Caesars (whose allegiance to the two Augusti was cemented by marriage to their daughters). Together, the four emperors ruled without strife until Diocletian retired in 305. Without his leadership, the tetrarchic form of government collapsed and renewed civil war followed. The division of the Roman Empire into eastern and western spheres survived, however. It persisted throughout the Middle Ages, setting the Latin West apart from the Byzantine East.

200 Chapter 7 T H E RO M A N E M P I R E

0 |

10 |

20 |

30 feet |

N |

|||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

5 |

|

|

10 meters |

|

||

7-72 Restored view (top) and plan (bottom) of the Temple of Venus, Baalbek, Lebanon, third century CE.

This “baroque” temple violates almost every rule of Classical design. It has a scalloped platform and entablature, five-sided Corinthian capitals, and a facade with an arch inside the triangular pediment.

TETRARCHIC PORTRAITURE The four tetrarchs often were portrayed together, both on coins and in the round. Artists did not try to capture their individual appearances and personalities but sought instead to represent the nature of the tetrarchy itself—that is, to portray four equal partners in power. In the two pairs of porphyry (purple marble) portraits of the tetrarchs (FIG. 7-73) that are now embedded in the southwestern corner of Saint Mark’s in Venice, it is impossible to name the rulers. Each of the four emperors has lost his identity as an individual and been subsumed into the larger entity of the tetrarchy. All the tetrarchs are identically clad in cuirass and cloak. Each grasps a sheathed sword in the left hand. With their right arms they embrace one another in an overt display of concord. The figures, like those on the decursio relief (FIG. 7-58) of the Column of Antoninus Pius, have large cubical heads on squat bodies. The drapery is schematic and the bodies are shapeless. The faces are emotionless masks, distinguished only by the beard on two of the figures

1 ft.

7-73 Portraits of the four tetrarchs, from Constantinople, ca. 305 CE. Porphyry, 4 3 high. Saint Mark’s, Venice.

Diocletian established the tetrarchy to bring order to the Roman world. In group portraits, artists always depicted the four co-rulers as nearly identical partners in power, not as distinct individuals.

(probably the older Augusti, distinguishing them from the younger Caesars). Nonetheless, each pair is as alike as freehand carving can achieve. In this group portrait, carved eight centuries after Greek sculptors first freed the human form from the formal rigidity of the Egyptian-inspired kouros stance, an artist once again conceived the human figure in iconic terms. Idealism, naturalism, individuality, and personality now belonged to the past.

PALACE OF DIOCLETIAN When Diocletian abdicated in 305, he returned to Dalmatia (roughly the area of the former Yugoslavia), where he was born. There he built a palace (FIG. 7-74) for himself at Split, near ancient Salona on the Adriatic coast of Croatia. Just as Aurelian had felt it necessary to girdle Rome with fortress walls, Diocletian instructed his architects to provide him with a wellfortified suburban palace. The complex, which covers about 10 acres, has the layout of a Roman castrum, complete with watchtowers flanking the gates. It gave the emperor a sense of security in the most insecure of times.

Within the high walls, two avenues (comparable to the cardo and decumanus of a Roman city; FIG. 7-42) intersected at the palace’s center. Where a city’s forum would have been situated, Diocletian’s palace had a colonnaded court leading to the entrance to the

Late Empire |

201 |

7-74 Restored view of the palace of Diocletian, Split, Croatia, ca. 298–306.

Diocletian’s palace resembled a fortified Roman city (compare FIG. 7-42). Within its high walls, two avenues intersected at the forumlike colonnaded courtyard leading to the emperor’s residential quarters.

imperial residence, which had a templelike facade with an arch within its pediment, as in the Temple of Venus (FIG. 7-72) at Baalbek. Diocletian wanted to appear like a god emerging from a temple when he addressed those who gathered in the court to pay homage to him. On one side of the court was a Temple of Jupiter. On the other side was Diocletian’s mausoleum (FIG. 7-74, center right), which towered above all the other structures in the complex. The emperor’s huge domed tomb was a type that would become very popular in Early Christian times not only for mausoleums but eventually also for churches, especially in the Byzantine East. In fact, the tomb is a church today.

Constantine

An all-too-familiar period of conflict followed the short-lived concord among the tetrarchs that ended with Diocletian’s abdication. This latest war among rival Roman armies lasted two decades. The eventual victor was Constantine I (“the Great”), son of Constantius Chlorus, Diocletian’s Caesar of the West. After the death of his father, Constantine invaded Italy. In 312, at the battle of the Milvian Bridge to Rome, he defeated and killed Maxentius and took control of the capital. Constantine attributed his victory to the aid of the Christian god. The next year, he and Licinius, Constantine’s coemperor in the East, issued the Edict of Milan, ending the persecution of Christians.

In time, Constantine and Licinius became foes, and in 324 Constantine defeated and executed Licinius near Byzantium (modern Istanbul, Turkey). Constantine, now unchallenged ruler of the whole Roman Empire, founded a “New Rome” at Byzantium and named it Constantinople (“City of Constantine”). In 325, at the Council of Nicaea, Christianity became the de facto official religion of the Roman Empire. From this point on, paganism declined rapidly. Constantinople was dedicated on May 11, 330, “by the commandment of

God,” and in 337 Constantine was baptized on his deathbed. For many scholars, the transfer of the seat of power from Rome to Constantinople and the recognition of Christianity mark the end of antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

Constantinian art is a mirror of this transition from the classical to the medieval world. In Rome, for example, Constantine was a builder in the grand tradition of the emperors of the first, second, and early third centuries, erecting public baths, a basilica on the road leading into the Roman Forum, and a triumphal arch. But he was also the patron of the city’s first churches (see Chapter 8).

ARCH OF CONSTANTINE Between 312 and 315, Constantine erected a great triple-passageway arch (FIGS. 7-2, no. 15, and 7-75) next to the Colosseum to commemorate his defeat of Maxentius. The arch was the largest erected in Rome since the end of the Severan dynasty. Much of the sculptural decoration, however, was taken from earlier monuments of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius, and all of the columns and other architectural elements date to an earlier era. Sculptors refashioned the second-century reliefs to honor Constantine by recutting the heads of the earlier emperors with the features of the new ruler. They also added labels to the old reliefs, such as Liberator Urbis (liberator of the city) and Fundator Quietus (bringer of peace), references to the downfall of Maxentius and the end of civil war. The reuse of statues and reliefs on the Arch of Constantine has often been cited as evidence of a decline in creativity and technical skill in the waning years of the pagan Roman Empire. Although such a judgment is in large part deserved, it ignores the fact that the reused sculptures were carefully selected to associate Constantine with the “good emperors” of the second century. That message is underscored in one of the arch’s few Constantinian reliefs. It shows Constantine on the speaker’s platform in the Roman Forum between statues of Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius.

202 Chapter 7 T H E RO M A N E M P I R E

7-75 Arch of Constantine (south side), Rome, Italy, 312–315 CE.

Much of the sculptural decoration of Constantine’s arch came from monuments of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius. Sculptors recut the heads of the earlier emperors with Constantine’s features.

In another Constantinian relief (FIG. 7-76), the emperor distributes largesse to grateful citizens who approach him from right and left. Constantine is a frontal and majestic presence, elevated on a throne above the recipients of his munificence. The figures are squat in proportion, like the tetrarchs (FIG. 7-73). They do not move according to any Classical principle of naturalistic movement but

1 ft.

7-76 Distribution of largesse, detail of the north frieze of the Arch of Constantine, Rome, Italy, 312–315 CE. Marble, 3 4 high.

This Constantinian frieze is less a narrative of action than a picture of actors frozen in time. The composition’s rigid formality reflects the new values that would come to dominate medieval art.

rather have the mechanical and repeated stances and gestures of puppets. The relief is very shallow, the forms are not fully modeled, and the details are incised. The frieze is less a narrative of action than a picture of actors frozen in time so that the viewer can distinguish instantly the all-important imperial donor (at the center on a throne) from his attendants (to the left and right above) and the recipients of the largesse (below and of smaller stature).

This approach to pictorial narrative was once characterized as a “decline of form,” and when judged by the standards of Classical art, it was. But the composition’s rigid formality, determined by the rank of those portrayed, was consistent with a new set of values. It soon became the preferred mode, supplanting the Classical notion that a picture is a window onto a world of anecdotal action. Comparing this Constantinian relief with a Byzantine icon (FIG. 9-18) reveals that the compositional principles of the Late Antique style are those of the Middle Ages. They were very different from—but not necessarily “better” or “worse” than—those of the Greco-Roman world. The Arch of Constantine is the quintessential monument of its era, exhibiting a respect for the past in its reuse of second-century sculptures while rejecting the norms of Classical design in its frieze, paving the way for the iconic art of the Middle Ages.

COLOSSUS OF CONSTANTINE After Constantine’s victory over Maxentius, his official portraits broke with tetrarchic tradition as well as with the style of the soldier emperors, and resuscitated the Augustan image of an eternally youthful head of state. The most impressive of Constantine’s preserved portraits is an eight- and-one-half-foot-tall head (FIG. 7-77), one of several marble

Late Empire |

203 |

fragments of a colossal enthroned statue |

7-77 Portrait of |

|

of the emperor composed of a brick core, |

Constantine, from the |

|

a wooden torso covered with bronze, and |

Basilica Nova, Rome, |

|

a head and limbs of marble. Constantine’s |

Italy, ca. 315–330 CE. |

|

artist modeled the seminude seated por- |

Marble, 8 6 high. |

|

Musei Capitolini, Rome. |

||

trait on Roman images of Jupiter. The em- |

||

|

||

peror held an orb (possibly surmounted |

Constantine’s portraits |

|

by the cross of Christ), the symbol of |

revive the Augustan |

|

global power, in his extended left hand. |

image of an eternally |

|

youthful ruler. This |

||

The nervous glance of third-century por- |

||

colossal head is one of |

||

traits is absent, replaced by a frontal mask |

||

several fragments of an |

||

with enormous eyes set into the broad |

||

enthroned Jupiter-like |

||

and simple planes of the head. The em- |

||

statue of the emperor |

||

peror’s personality is lost in this immense |

||

holding the orb of |

||

image of eternal authority. The colossal |

world power. |

|

size, the likening of the emperor to |

|

Jupiter, the eyes directed at no person or thing of this world—all combine to produce a formula of overwhelming power appropriate to Constantine’s exalted position as absolute ruler.

BASILICA NOVA, ROME Constantine’s gigantic portrait sat |

|

in the western apse of the Basilica Nova (“New Basilica,” FIGS. 7-2, |

|

no. 12, and 7-78), a project Maxentius had begun and Constantine |

|

completed. From its position in the apse, the emperor’s image dom- |

|

inated the interior of the basilica in much the same way that en- |

|

throned statues of Greco-Roman divinities loomed over awestruck |

|

mortals who entered the cellas of pagan temples. |

|

7-78 Restored cutaway view of the Basilica Nova, Rome, Italy, |

|

ca. 306–312 CE (John Burge). |

|

The lessons learned in the construction of baths and market halls were |

1 ft. |

applied to the Basilica Nova, where fenestrated concrete groin vaults |

|

replaced the clerestory of a traditional stone-and-timber basilica. |

|

204 Chapter 7 T H E RO M A N E M P I R E

7-79 Aula Palatina (exterior), Trier, Germany, early fourth century CE.

The austere brick exterior of Constantine’s Aula Palatina at Trier is typical of later Roman architecture. Two stories of windows with lead-framed panes of glass take up most of the surface area.

The Basilica Nova ruins never fail to impress tourists with their size and mass. The original structure was 300 feet long and 215 feet wide. Brickfaced concrete walls 20 feet thick supported coffered barrel vaults in the aisles. These vaults also buttressed the groin vaults of the nave, which was 115 feet high. The walls and floors were richly marbled and stuccoed. The reconstruction in FIG. 7-78 effectively suggests the immensity of the interior, where the great vaults dwarf even the emperor’s colossal portrait. The drawing also clearly reveals the fenestration of the groin vaults, a lighting system akin to the clerestory of a traditional stone-and-timber basilica. Here, Roman builders applied to the Roman basilica the lessons learned in the design and construction of buildings such as Trajan’s great market hall (FIG. 7-46) and the Baths of Diocletian (FIG. 7-67).

AULA PALATINA, TRIER At Trier (ancient Augusta Treverorum) on the Moselle River in Germany, the imperial seat of Constantius Chlorus as Caesar of the West, Constantine built a new palace complex. It included a basilica-like audience hall, the Aula Palatina (FIG. 7-79), of traditional form and materials. The Aula Palatina measures about 190 feet long and 95 feet wide and has an austere brick exterior, which was enlivened somewhat by highlighting in grayish white stucco. The use of lead-framed panes of glass for the windows enabled the builders to give life and movement to the blank exterior surfaces.

Inside (FIG. 7-80), the audience hall was also very simple. Its flat, wooden, coffered ceiling is some 95 feet above the floor. The interior has no aisles, only a wide space with two stories of large windows that provide ample light. At the narrow north end, the main hall is divided from the semicircular apse (which also has a flat ceiling) by a so-called chancel arch. The Aula Palatina’s interior is quite severe, although marble veneer and mosaics originally covered the arch and apse to provide a magnificent environment for the enthroned emperor. The design of both the interior and exterior has close parallels in many Early Christian churches.

7-80 Aula Palatina (interior), Trier, Germany, early fourth century CE.

The interior of the audience hall of Constantine’s palace complex in Germany resembles a timberroofed basilica with an apse at one end, but it has no aisles. The large windows provided ample illumination.

Late Empire |

205 |

CONSTANTINIAN COINS The two portraits of Constantine on the coins in FIG. 7-81 reveal both the essential character of Roman imperial portraiture and the special nature of Constantinian art. The first (FIG. 7-81, left) was issued shortly after the death of Constantine’s father, when Constantine was in his early 20s and his position was still insecure. Here, in his official portrait, he appears considerably older, because he adopted the imagery of the tetrarchs. Indeed, were it not for the accompanying label identifying this Caesar as Constantine, it would be impossible to know who was portrayed. Eight years later (FIG. 7-81, right)—after the defeat of Maxentius and the Edict of Milan—Constantine, now the unchallenged Augustus of the West, is clean-shaven and looks his actual 30 years of age, having rejected the mature tetrarchic look in favor of youth. These two coins should dispel any uncertainty about the often fictive nature of imperial portraiture and the ability of Roman emperors to choose any official image that suited

their needs. In Roman art, “portrait” is often not synonymous with “likeness.”

The later coin is also an eloquent testimony to the dual nature of Constantinian rule. The emperor appears in his important role as imperator, dressed in armor, wearing an ornate helmet, and carrying a shield bearing the enduring emblem of the Roman state—the shewolf nursing Romulus and Remus (compare FIG. 6-11 and Roma’s shield in FIG. 7-57). Yet he does not carry the scepter of the pagan Roman emperor. Rather, he holds a cross crowned by an orb. In addition, at the crest of his helmet, at the front, just below the grand plume, is a disk containing the Christogram, the monogram made up of chi (X), rho (P), and iota (I), the initial letters of Christ’s name in Greek (compare the shield one of the soldiers holds in FIG. 9-10). Constantine was at once portrayed as Roman emperor and as a soldier in the army of the Lord. The coin, like Constantinian art in general, belongs both to the classical and to the medieval world.

7-81 Coins with portraits of Constantine. Nummus (left), 307 CE.

Society, New York. Medallion (right), ca. 315 CE. Silver, diameter 1 . Staatliche Münzsammlung, Munich.

These two coins underscore that portraits of Roman emperors are rarely true likenesses. On the earlier coin, Constantine appears as a bearded tetrarch. On the later coin, he appears eternally youthful.

206 Chapter 7 T H E RO M A N E M P I R E