C7

.pdf

A R C H I T E C T U R A L B A S I C S

The Roman House

The Roman house was more than just a place to live. It played an important role in Roman societal rituals. In the Roman world, individuals were frequently bound to others in a patron-client relationship whereby a wealthier, better-educated, and more powerful patronus would protect the interests of a cliens, sometimes large numbers of them. The standing of a patron in Roman society often was measured by clientele size. Being seen in public accompanied by a crowd of clients was a badge of honor. In this system, a plebeian might be bound to a patrician, a freed slave to a former owner, or even one patrician to another. Regardless of rank, all clients were obligated to support their patron in political campaigns and to perform specific services on request, as well as to call on and salute the

patron at the patron’s home.

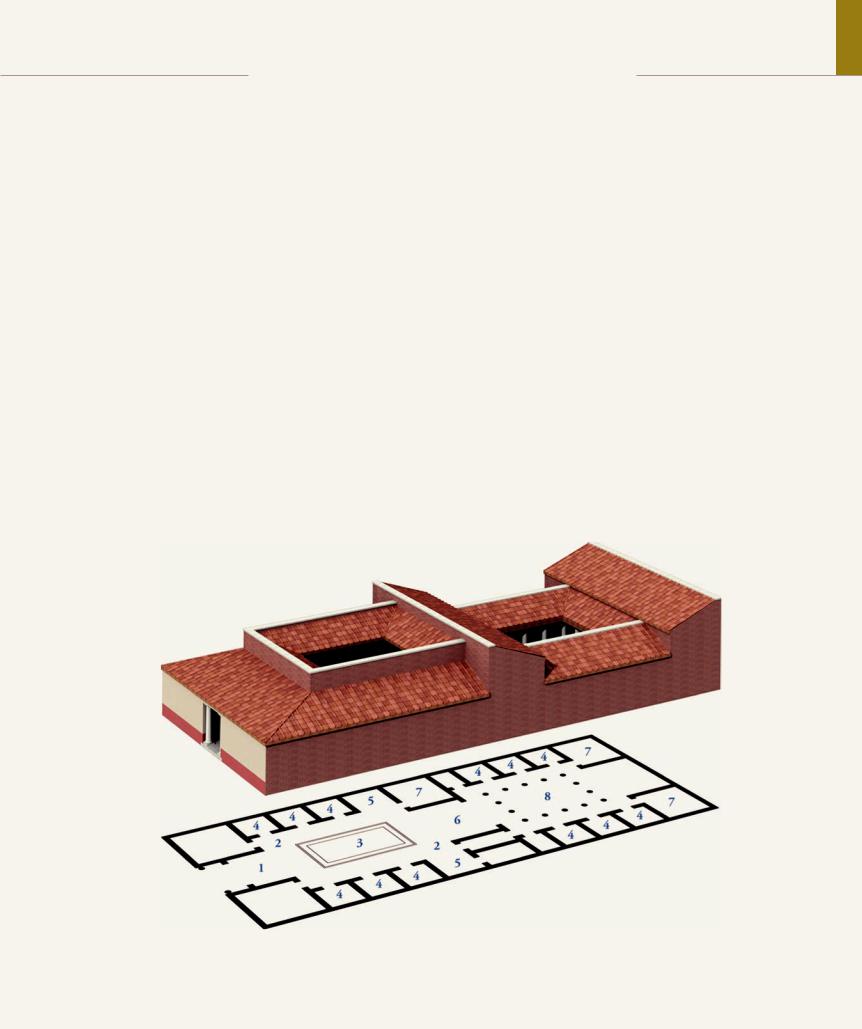

A client calling on a patron would enter the typical Roman domus (private house) through a narrow fauces (the “jaws” of the house), which led to a large central reception area, the atrium. The rooms flanking the fauces could open onto the atrium, as in FIG. 7-16, or onto the street, in which case they were rented out as shops. The roof over the atrium was partially open to the sky, not only to admit light but also to channel rainwater into a basin (impluvium) below. The water could be stored in cisterns for household use. Opening onto the atrium was a series of small bedrooms called cubicula (cubicles). At the back were two recessed areas (alae, wings) and the patron’s tablinum or “home office,” a dining room (triclinium), a kitchen, and sometimes a small garden.

Endless variations of the same basic plan exist, dictated by an owner’s personal tastes and means, the size and shape of the lot purchased, and so forth, but all Roman houses of this type were inwardlooking in nature. The design shut off the street’s noise and dust, and all internal activity focused on the brightly illuminated atrium at the center of the residence. This basic module (only the front half of the typical house in FIG. 7-16) resembles the plan of the typical Etruscan house as reflected in the Tomb of the Shields and Chairs (FIG. 6-7) and other tombs at Cerveteri. Thus, few scholars doubt that the early Roman house, like the early Roman temple, grew out of the Etruscan tradition.

During the second century BCE, when Roman architects were beginning to construct stone temples with Greek columns, the Roman house also took on Greek airs. Builders added a peristyle garden behind the Etruscan-style house, providing a second internal source of illumination as well as a pleasant setting for meals served in a summer triclinium. The axial symmetry of the plan meant that on entering the fauces of the house, a visitor could be greeted by a vista through the atrium directly into the peristyle garden (as in FIG. 7-15), which often boasted a fountain or pool, marble statuary, mural paintings, and mosaic floors.

While such private houses were typical of Pompeii and other Italian towns, they were very rare in large cities such as Rome, where the masses lived instead in multistory apartment houses (FIG. 7-54).

7-16 Restored view and plan of a typical Roman house of the Late Republic and Early Empire (John Burge).

(1) fauces, (2) atrium, (3) impluvium, (4) cubiculum, (5) ala, (6) tablinum, (7) triclinium, (8) peristyle.

Older Roman houses closely followed Etruscan models and had atriums and small gardens, but during the Late Republic and Early Empire, Roman builders added peristyles with Greek columns.

Pompeii and the Cities of Vesuvius |

167 |

7-17 First Style wall painting in the fauces of the Samnite House, Herculaneum, Italy, late second century BCE.

In First Style murals, the decorator’s aim was to imitate costly marble panels using painted stucco relief. The style is Greek in origin and another example of the Hellenization of Republican architecture.

FIRST STYLE The First Style is also called the Masonry Style because the decorator’s aim was to imitate costly marble panels using painted stucco relief. The fauces (FIG. 7-17) of the Samnite House at Herculaneum greets the visitor with a stunning illusion of walls constructed, or at least faced, with marbles imported from quarries all over the Mediterranean. This approach to wall decoration is comparable to the modern practice, employed in private libraries and corporate meeting rooms alike, of using cheaper manufactured materials to approximate the look and shape of genuine wood paneling. The practice is not, however, uniquely Pompeian or Roman. First Style walls are well documented in the Greek world from the late fourth century BCE on. The use of the First Style in Republican houses is yet another example of the Hellenization of Roman architecture.

168 Chapter 7 T H E RO M A N E M P I R E

SECOND STYLE The First Style never went completely out of fashion, but after 80 BCE a new approach to mural design became more popular. The Second Style is in most respects the antithesis of the First Style. Some scholars have argued that the Second Style also has precedents in Greece, but most believe it is a Roman invention. Certainly, the Second Style evolved in Italy and was popular until around 15 BCE, when Roman painters introduced the Third Style. Second Style painters did not aim to create the illusion of an elegant marble wall, as First Style painters sought to do. Rather, they wanted to dissolve a room’s confining walls and replace them with the illusion of an imaginary three-dimensional world.

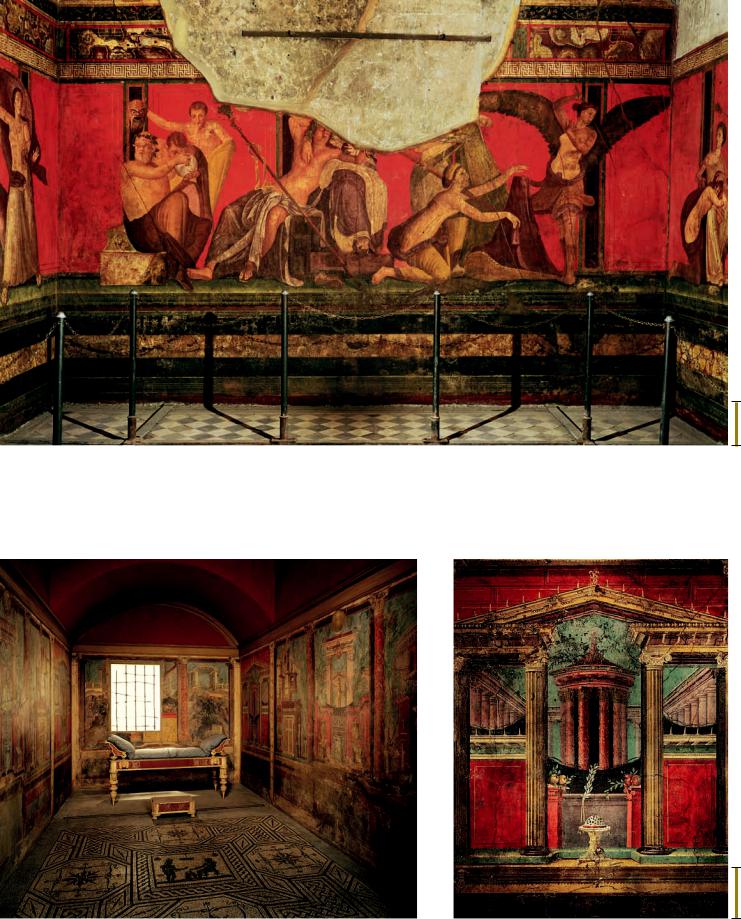

VILLA OF THE MYSTERIES An early example of the new style is the room (FIG. 7-18) that gives its name to the Villa of the Mysteries at Pompeii. Many scholars believe this chamber was used to celebrate, in private, the rites of the Greek god Dionysos (Roman Bacchus). Dionysos was the focus of an unofficial mystery religion popular among women in Italy at this time. The precise nature of the Dionysiac rites is unknown, but the figural cycle in the Villa of the Mysteries, illustrating mortals (all female save for one boy) interacting with mythological figures, probably provides some evidence for the cult’s initiation rites. In these rites young women, emulating Ariadne, daughter of King Minos (see Chapter 4), united in marriage with Dionysos.

The backdrop for the nearly life-size figures is a series of painted panels imitating marble revetment, just as in the First Style but without the modeling in relief. In front of this marble wall (but actually on the same two-dimensional surface), the painter created the illusion of a shallow ledge on which the human and divine actors move around the room. Especially striking is the way some of the figures interact across the corners of the room. For example, a seminude winged woman at the far right of the rear wall lashes out with her whip across the space of the room at a kneeling woman with a bare back (the initiate and bride-to-be of Dionysos) on the left end of the right wall. Nothing comparable to this room existed in Hellenistic Greece. Despite the presence of Dionysos, satyrs, and other figures from Greek mythology, this is a Roman design.

VILLA AT BOSCOREALE In the early Second Style Dionysiac mystery frieze, the spatial illusionism is confined to the painted platform that projects into the room. But in mature Second Style designs, Roman painters created a three-dimensional setting that also extends beyond the wall. An example is a cubiculum (FIG. 7-19) from the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, near Pompeii, decorated between 50 and 40 BCE. The excavators removed the frescoes soon after their discovery, and today they are part of a reconstructed Roman bedroom in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. All around the room the Second Style painter opened up the walls with vistas of Italian towns, marble temples, and colonnaded courtyards. Painted doors and gates invite the viewer to walk through the wall into the magnificent world the painter created.

Although the Boscoreale painter was inconsistent in applying it, this Roman artist, like many others around the Bay of Naples, demonstrated a knowledge of single-point linear perspective, often incorrectly said to be an innovation of Italian Renaissance artists (see “Renaissance Perspectival Systems,” Chapter 16, page 425). In this kind of perspective, all the receding lines in a composition converge on a single point along the painting’s central axis to show depth and distance. Ancient writers noted that Greek painters of the fifth century BCE first used linear perspective for the design of Athenian stage sets (hence its Greek name, skenographia, “scene painting”). In the Boscoreale cubiculum, the painter most successfully employed the device in the far corners, where a low gate leads to a

1 ft.

7-18 Dionysiac mystery frieze, Second Style wall paintings in room 5 of the Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii, Italy, ca. 60–50 BCE. Fresco, frieze 5 4 high.

Second Style painters created the illusion of an imaginary three-dimensional world on the walls of Roman houses. The figures in this room are acting out the initiation rites of the Dionysiac mysteries.

1 ft.

7-19 Second Style wall paintings (general view, left, and detail of tholos, right) from cubiculum M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, Fresco, 8 9 high. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In this Second Style bedroom, the painter opened up the walls with vistas of towns, temples, and colonnaded courtyards. The convincing illusionism is due in part to the use of linear perspective.

1 ft.

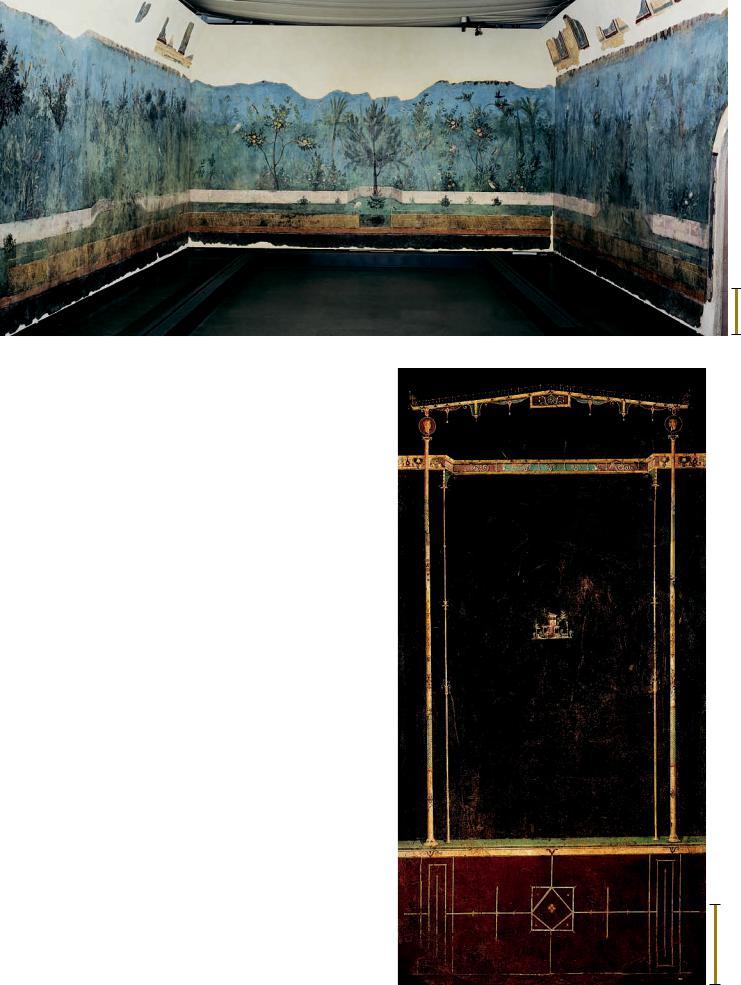

7-20 Gardenscape, Second Style wall paintings, from the Villa of Livia, Primaporta, Italy, ca. 30–20 BCE. Fresco, 6 7 high. Museo

Nazionale Romano–Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome.

The ultimate example of a Second Style “picture-window” wall is Livia’s gardenscape. To suggest recession, the painter used atmospheric perspective, intentionally blurring the most distant forms.

peristyle framing a tholos temple (FIG. 7-19, right). Linear perspective was a favored tool of Second Style painters seeking to transform the usually windowless walls of Roman houses into “picturewindow” vistas that expanded the apparent space of the rooms.

VILLA OF LIVIA, PRIMAPORTA The ultimate example of a Second Style picture-window mural (FIG. 7-20) comes from the Villa of Livia, wife of the emperor Augustus, at Primaporta, just north of Rome. There, imperial painters decorated all the walls of a vaulted room with lush gardenscapes. The only architectural element is the flimsy fence of the garden itself. To suggest recession, the painter mastered another kind of perspective, atmospheric perspective, indicating depth by the increasingly blurred appearance of objects in the distance. At Livia’s villa, the artist precisely painted the fence, trees, and birds in the foreground, whereas the details of the dense foliage in the background are indistinct. Among the wall paintings examined so far, only the landscape fresco (FIG. 4-9) from Thera offers a similar wraparound view of nature. But the Aegean fresco’s white sky and red, yellow, and blue rock formations do not create a successful illusion of a world filled with air and light just a few steps away.

7-21 Detail of a Third Style wall painting, from cubiculum 15 of the Villa of Agrippa Postumus, Boscotrecase, Italy, ca. 10 BCE. Fresco, 7 8 high. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

1 ft.

In the Third Style, Roman painters decorated walls with delicate linear fantasies sketched on predominantly monochromatic backgrounds. Here, a tiny floating landscape on a black ground is the central motif.

170 Chapter 7 T H E RO M A N E M P I R E

THIRD STYLE The Primaporta gardenscape is the polar opposite of First Style designs, which reinforce, rather than deny, the heavy presence of confining walls. But tastes changed rapidly in the Roman world, as in society today. Not long after Livia had her villa painted, Roman patrons began to favor mural designs that reasserted the primacy of the wall surface. In the Third Style of Pompeian painting, artists no longer attempted to replace the walls with three-dimensional worlds of their own creation. Nor did they seek to imitate the appearance of the marble walls of Hellenistic kings. Instead they decorated walls with delicate linear fantasies sketched on predominantly monochromatic (one-color) backgrounds.

VILLA AT BOSCOTRECASE One of the earliest examples of the new style is a cubiculum (FIG. 7-21) in the Villa of Agrippa Postumus at Boscotrecase. The villa was probably painted just before 10 BCE. Nowhere did the artist use illusionistic painting to penetrate the wall. In place of the stately columns of the Second Style are insubstantial and impossibly thin colonnettes supporting featherweight canopies barely reminiscent of pediments. In the center of this delicate and elegant architectural frame is a tiny floating landscape painted directly on the jet black ground. It is hard to imagine a sharper contrast with the panoramic gardenscape at Livia’s villa. On other Third Style walls, landscapes and mythological scenes appear

in frames, like modern canvas paintings hung on walls. Never could these framed panels be mistaken for windows opening onto a world beyond the room.

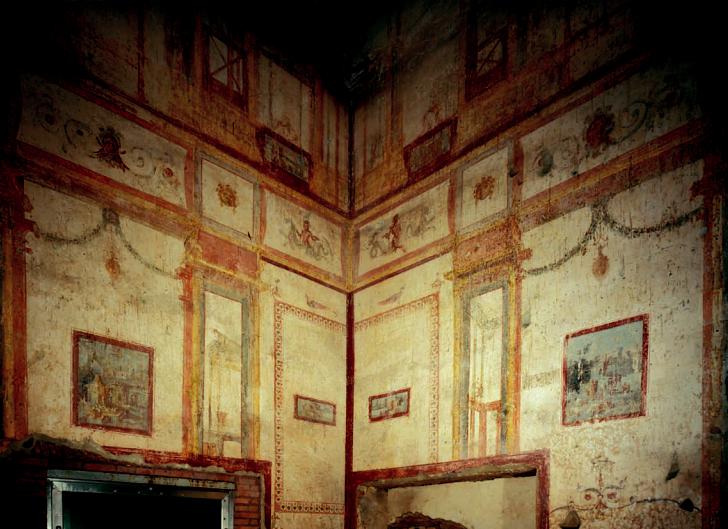

FOURTH STYLE In the Fourth Style, however, a taste for illusionism returned once again. This style became popular in the 50s CE, and it was the preferred manner of mural decoration at Pompeii when the eruption of Vesuvius buried the town in volcanic ash in 79. Some examples of the new style, such as room 78 (FIG. 7-22) in the emperor Nero’s Golden House in Rome (see page 179), display a kinship with the Third Style. All the walls are an austere creamy white. In some areas the artist painted sea creatures, birds, and other motifs directly on the monochromatic background, much like the landscape in the Boscotrecase villa (FIG. 7-21). Landscapes appear here too—as framed paintings in the center of each large white subdivision of the wall. Views through the wall are also part of the design, but the Fourth Style architectural vistas are irrational fantasies. The viewer looks out not on cityscapes or round temples set in peristyles but at fragments of buildings—columns supporting halfpediments, double stories of columns supporting nothing at all— painted on the same white ground as the rest of the wall. In the Fourth Style, architecture became just another motif in the painter’s ornamental repertoire.

7-22 Fourth Style wall paintings in room 78 of the Domus Aurea (Golden House) of Nero, Rome, Italy, 64–68 CE.

The creamy white walls of this room in Nero’s Golden House display a kinship with the Third Style, but views through the wall revealing irrational architectural vistas characterize the new Fourth Style.

Pompeii and the Cities of Vesuvius |

171 |

7-23 Fourth Style wall paintings in the Ixion Room (triclinium P) of the House of the Vettii, Pompeii, Italy, ca. 70–79 CE.

Late Fourth Style murals are often garishly colored, crowded, and confused compositions with a mixture of architectural views, framed mythological panel paintings, and First and Third Style motifs.

IXION ROOM In the latest Fourth Style designs, Pompeian painters rejected the quiet elegance of the Third Style and early Fourth Style in favor of crowded and confused compositions and sometimes garish color combinations. The Ixion Room (FIG. 7-23) of the House of the Vettii at Pompeii was decorated in this manner just before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The room served as a triclinium in the house the Vettius brothers remodeled after the earthquake. It opened onto the peristyle seen in the background of

FIG. 7-15.

The decor of the Ixion Room serves as a synopsis of all the previous styles, another instance of the eclecticism noted earlier as characteristic of Roman art in general. The lowest zone, for example, is one of the most successful imitations anywhere of costly multicolored imported marbles, despite the fact that the painter created the illusion without recourse to relief, as in the First Style. The large white panels in the corners of the room, with their delicate floral frames and floating central motifs, would fit naturally into the most elegant Third Style design. Unmistakably Fourth Style, however, are the fragmentary architectural vistas of the

central and upper zones of the walls. They are unrelated to one another, do not constitute a unified cityscape beyond the wall, and incorporate figures that would tumble into the room if they took a single step forward.

The Ixion Room takes its name from the mythological panel painting at the center of the rear wall (FIG. 7-23). Ixion had attempted to seduce Hera, and Zeus punished him by binding him to a perpetually spinning wheel. The panels on the two side walls also have Greek myths as subjects. The Ixion Room may be likened to a small private art gallery with paintings decorating the walls, as in many modern homes. Scholars long have believed that these and the many other mythological paintings on Third and Fourth Style walls were based on lost Greek panels. They attest to the Romans’ continuing admiration for Greek artworks three centuries after Marcellus brought the treasures of Syracuse to Rome. But few, if any, of these mythological paintings can be described as true copies of “Old Masters,” as are the many Roman replicas of famous Greek statues that have been found throughout the Roman world, including Pompeii (FIG. 5-40).

172 Chapter 7 T H E RO M A N E M P I R E

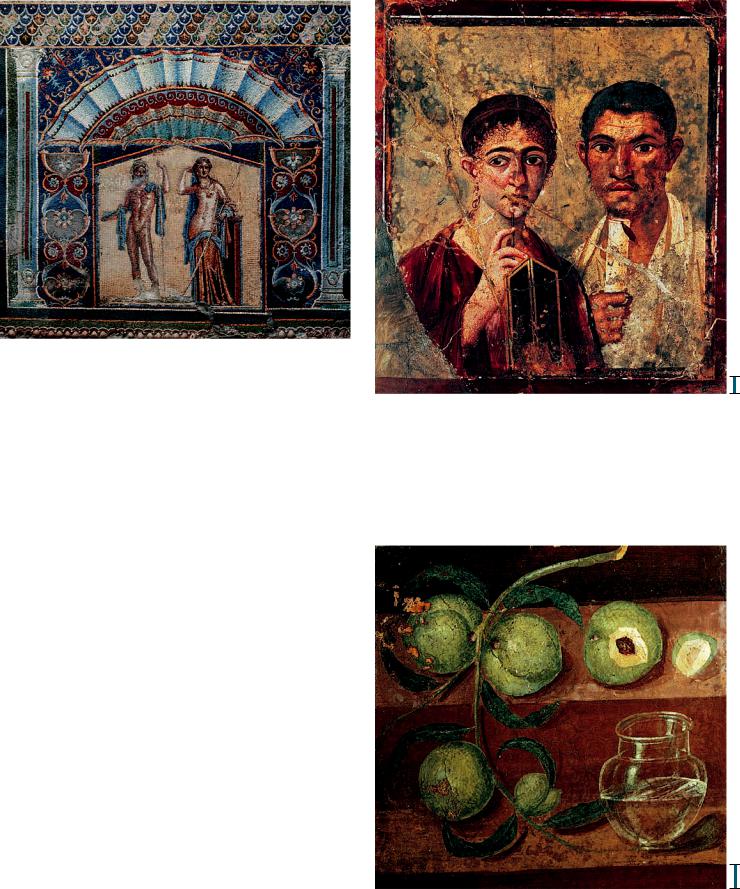

WALL MOSAICS Mythological figures were on occasion also the subject of Roman mosaics. In the ancient world, mosaics were usually confined to floors (as was the Pompeian Alexander Mosaic, FIG. 5-70), where the tesserae formed a durable as well as decorative surface. In Roman times, however, mosaics also decorated walls and even ceilings, foreshadowing the extensive use of wall and vault mosaics in the Middle Ages (see “Mosaics,” Chapter 8, page 223). The mosaic shown in FIG. 7-24 adorns a wall in the House of Neptune and Amphitrite at Herculaneum. The statuesque figures of the sea god and his wife preside over the running water of the fountain in the courtyard in front of them where the home’s owners and guests enjoyed outdoor dining in warm weather.

PRIVATE PORTRAITS The subjects chosen for Roman wall paintings and mosaics were diverse. Although mythological themes were immensely popular, Romans commissioned a vast range of other subjects. As noted, landscape paintings frequently appear on Second, Third, and Fourth Style walls. Paintings and mosaics depicting scenes from history include the Alexander Mosaic (FIG. 5-70) and

7-24 Neptune and Amphitrite, wall mosaic in the summer triclinium of the House of Neptune and Amphitrite, Herculaneum, Italy,

ca. 62–79 CE.

In the ancient world, mosaics were usually confined to floors, but this example depicting Neptune and Amphitrite decorates the wall of a private house. The sea deities fittingly overlook an elaborate fountain.

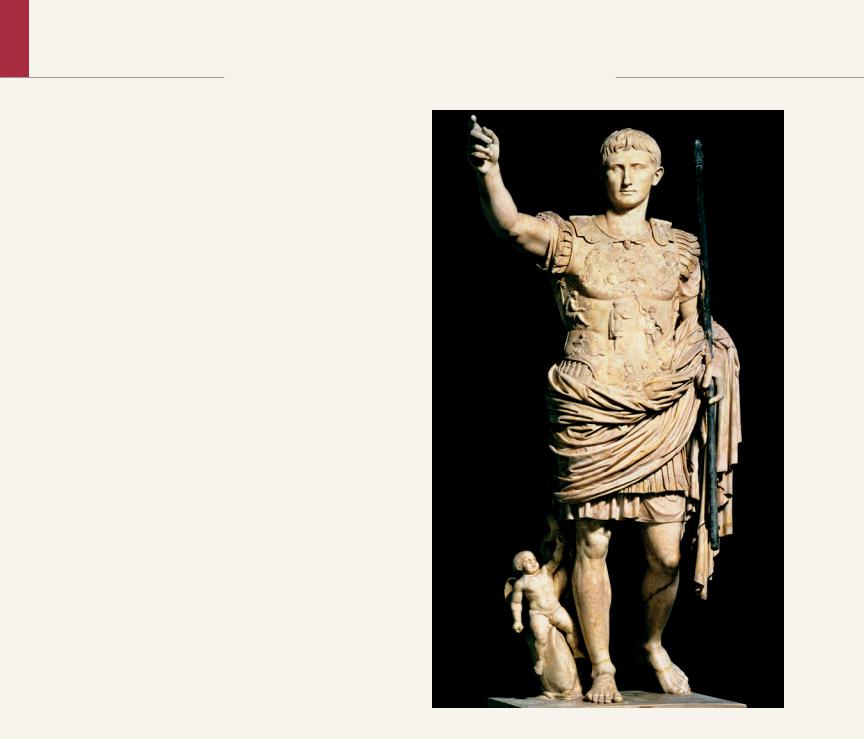

the mural painting (FIG. 7-14) of the brawl in the amphitheater of Pompeii. Given the Roman custom of keeping imagines of illustrious ancestors in atriums, it is not surprising that painted portraits also appear in Pompeian houses. The portrait of a husband and wife illustrated here (FIG. 7-25) originally formed part of a Fourth Style wall of an exedra, or recessed area, opening onto the atrium of a Pompeian house. The man holds a scroll and the woman a stylus (writing instrument) and a wax writing tablet, standard attributes in Roman marriage portraits. They suggest the fine education of those depicted—even if, as was sometimes true, the individuals were uneducated or even illiterate. Such portraits were thus the Roman equivalent of modern wedding photographs of the bride and groom posing in rented formal garments that they never wore before or afterward (see “Role Playing in Roman Portraiture,” page 174). In contrast, the heads are not standard types but sensitive studies of the couple’s individual faces. This is another instance of a realistic portrait placed on a conventional figure type (compare FIG. 7-8), a recurring phenomenon in Roman portraiture.

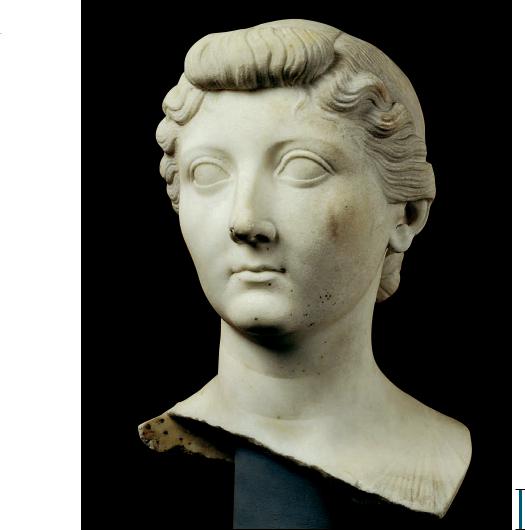

STILL-LIFE PAINTING The Roman interest in recording the unique appearance of individual people extended to everyday objects. This explains the frequent inclusion of still-life paintings (representations of inanimate objects, artfully arranged) in the mural schemes of the Second, Third, and Fourth Styles. A still life with peaches and a carafe (FIG. 7-26), a detail of a painted wall from Herculaneum, demonstrates that Roman painters sought to create illusionistic effects when depicting small objects as well as buildings and landscapes. The artist paid as much attention to shadows and highlights on the fruit, the stem and leaves, and the glass jar as to the objects themselves. Art historians have not found evidence of paintings comparable to these Roman studies of food and other inanimate objects until the Dutch still lifes of the 17th and 18th centuries (FIGS. 20-22 and 20-23).

1 in.

7-25 Portrait of a husband and wife, wall painting from House

VII,2,6, Pompeii, Italy, ca. 70–79 CE. Fresco, 1 11 1 8 – . Museo

1

2

Archeologico Nazionale, Naples.

This husband and wife wished to present themselves to their guests as thoughtful and well-read. The portraits are individualized likenesses, but the poses and attributes they hold are standard types.

1 in.

7-26 Still life with peaches, detail of a Fourth Style wall painting,

from Herculaneum, Italy, ca. 62–79 CE. Fresco, 1 2 1 1 |

1 |

– . Museo |

|

Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. |

2 |

|

The Roman interest in illusionism explains the popularity of still-life paintings. This painter paid scrupulous attention to the play of light and shadow on different shapes and textures.

Pompeii and the Cities of Vesuvius |

173 |

A R T A N D S O C I E T Y

Role Playing in Roman Portraiture

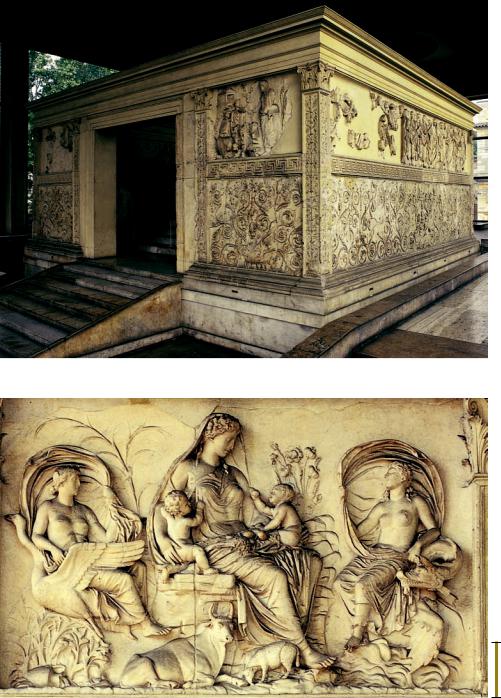

In every town throughout the vast Roman Empire, portraits of the emperors and empresses and their families were on display—in forums, basilicas, baths, and markets; in front of temples; atop triumphal arches—anywhere a statue could be placed. The rulers’ heads varied little from Britain to Syria. All were replicas of official images, either imported or scrupulously copied by local artists. But the Roman sculptors placed the portrait heads on many types of bodies. The type chosen depended on the position the person held in Roman society or the various fictitious guises members of the imperial family assumed. Portraits of Augustus, for example, show him not only as armed general (FIG. 7-27) but also as recipient of the civic crown for saving the lives of fellow citizens (FIG. I-9). Other statues show him as veiled priest, toga-clad magistrate, traveling commander on horseback, heroically nude warrior, and various Roman gods, in-

cluding Jupiter, Apollo, and Mercury.

Such role playing was not confined to emperors and princes but extended to their wives, daughters, sisters, and mothers. Portraits of Livia (FIG. 7-28) depict her as many goddesses, including Ceres, Juno, Venus, and Vesta. She also appears as the personification of Health, Justice, and Piety. In fact, it was common for imperial women to appear on Roman coins as goddesses or as embodiments of feminine virtue. Faustina the Younger, for example, the wife of Marcus Aurelius and mother of 13 children, appears as Venus and Fecundity, among many other roles. Julia Domna (FIG. 7-63), Septimius Severus’s wife, is Juno, Venus, Peace, or Victory in some portraits.

Ordinary citizens also engaged in role playing. Some assumed literary pretensions, as did a husband and wife (FIG. 7-25) in their Pompeian home. Others equated themselves with Greek heroes (FIG. 7-60) or Roman deities (FIG. 7-61) on their coffins. The common people followed the lead of the emperors and empresses.

7-27 Portrait of Augustus as general, from Primaporta, Italy, early-first-century CE copy of a bronze original of ca. 20 BCE. Marble, 6 8 high. Musei Vaticani, Rome.

Augustus’s idealized portraits were modeled on Classical Greek statues (FIG. 5-40) and depict him as a never-aging son of a god. This portrait presents the emperor in armor in his role as general.

EARLY EMPIRE

The murder of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March, 44 BCE, plunged the Roman world into a bloody civil war. The fighting lasted until 31 BCE when Octavian (better known as Augustus), Caesar’s grandnephew and adopted son, crushed the naval forces of Mark Antony and Queen Cleopatra of Egypt at Actium in northwestern Greece. Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide, and in 30 BCE, Egypt, once the wealthiest and most powerful kingdom of the ancient world, became another province in the ever-expanding Roman Empire.

Historians mark the passage from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire from the day in 27 BCE when the Senate conferred the majestic title of Augustus (r. 27 BCE–14 CE) on Octavian. The Empire was ostensibly a continuation of the Republic, with the same constitutional offices, but in fact Augustus, whom the Senate recog-

nized as princeps (first citizen), occupied all the key positions. He was consul and imperator (commander in chief; root of the word emperor) and even, after 12 BCE, pontifex maximus (chief priest of the state religion). These offices gave Augustus control of all aspects of Roman public life.

PAX ROMANA With powerful armies keeping order on the Empire’s frontiers and no opposition at home, Augustus brought peace and prosperity to a war-weary Mediterranean world. Known in his own day as the Pax Augusta (Augustan Peace), the peace Augustus established prevailed for two centuries. It came to be called simply the Pax Romana. During this time the emperors commissioned a huge number of public works throughout the Empire: roads, bridges, theaters, amphitheaters, and bathing complexes, all on an unprecedented scale. The erection of imperial portrait statues and monuments covered with reliefs recounting the rulers’ great

174 Chapter 7 T H E RO M A N E M P I R E

7-28 Portrait bust of Livia, from Arsinoe, Egypt,

early first century CE. Marble, 1 1 – high. Ny Carlsberg

1

2

Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

Although Livia sports the latest Roman coiffure, her youthful appearance and sharply defined features derive from images of Greek goddesses. She lived until 87, but, like Augustus, never aged in her portraits.

1 in.

deeds reminded people everywhere of the source of this beneficence. These portraits and reliefs often presented a picture of the emperors and their achievements that bore little resemblance to historical fact. Their purpose, however, was not to provide an objective record but to mold public opinion. The Roman emperors and the artists they employed have had few equals in the effective use of art and architecture for propagandistic ends.

Augustus and the Julio-Claudians

When Augustus vanquished Antony and Cleopatra at Actium and became undisputed master of the Mediterranean world, he was not yet 32 years old. The rule by elders that had characterized the Roman Republic for nearly a half millennium came to an abrupt end. Suddenly, Roman portraitists were called on to produce images of a youthful head of state. But Augustus was not merely young. Caesar had been made a god after his death, and Augustus, though never claiming to be a god himself, widely advertised himself as the son of a god. His portraits were designed to present the image of a godlike leader who miraculously never aged. Although Augustus lived until 14 CE, even official portraits made near the end of his life show him as a handsome youth (FIG. I-9). Such fictional portraits might seem ridiculous today, when the media circulate pictures of world leaders as they truly appear, but in antiquity few people had actually seen the emperor. His official image was all most knew. It therefore could be manipulated at will.

AUGUSTUS AS IMPERATOR The portraits of Augustus depict him in his many different roles in the Roman state (see “Role Playing in Roman Portraiture,” page 174), but the models for many of them were Classical Greek statues. The portrait (FIG. 7-27) of the emperor found at his wife Livia’s villa (FIG. 7-20) at Primaporta portrays Augustus as general, standing in the pose of Polykleitos’s Doryphoros (FIG. 5-40) but with his right arm raised to address his troops in the manner of the orator Aule Metele (FIG. 6-16). Augustus’s head, although portraying a recognizable individual, also emulates the idealized head of the Polykleitan spear bearer in its overall shape, the sharp ridges of the brows, and the tight cap of layered hair. Augustus is not a nude athlete, however, and the details of the statue carry political messages. The reliefs on the cuirass advertise an important diplomatic victory—the return of the Roman military standards the Parthians had captured from a Republican general—and the Cupid at Augustus’s feet alludes to his divine descent. (Caesar’s family, the Julians, traced their ancestry back to Venus. Cupid was the goddess’s son.)

LIVIA A marble portrait (FIG. 7-28) of Livia shows that the imperial women of the Augustan age shared the emperor’s eternal youthfulness. Although she sports the latest Roman coiffure, with the hair rolled over the forehead and knotted at the nape of the neck, Livia’s blemish-free skin and sharply defined features derive from images of Classical Greek goddesses. Livia outlived Augustus by 15 years, dying at age 87. In her portraits, the coiffure changed with the introduction of each new fashion, but her face remained ever young, befitting her exalted position in the Roman state.

Early Empire |

175 |

7-29 Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace; looking northeast), Rome, Italy, 13–9 BCE.

Augustus sought to present his new order as a Golden Age equaling that of Athens under Pericles. The Ara Pacis celebrates the emperor’s most important achievement, the establishment of peace.

7-30 Female personification (Tellus?), panel from the east facade of the Ara Pacis Augustae, Rome, Italy, 13–9 BCE. Marble, 5 3 high.

This female personification with two babies on her lap epitomizes the fruits of the Pax Augusta. All around her the bountiful earth is in bloom, and animals of different species live together peacefully.

ARA PACIS AUGUSTAE On Livia’s birthday in 9 BCE, Augustus dedicated the Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace; FIG. 7-29), the monument celebrating his most significant achievement, the establishment of peace. Figural reliefs and acanthus tendrils adorn the altar’s

marble precinct walls. Four panels on the east and west ends depict carefully selected mythological subjects, including (at the right in FIG. 7-29) a relief of Aeneas making a sacrifice. Aeneas was the son of Venus and one of Augustus’s forefathers. The connection between the emperor and Aeneas was a key element of Augustus’s political ideology for his new Golden Age. It is no coincidence that Vergil wrote the Aeneid during the rule of Augustus. The epic poem glorified the young emperor by celebrating the founder of the Julian line.

A second panel (FIG. 7-30), on the other end of the altar enclosure, depicts a seated matron with two lively babies on her lap. Her identity is uncertain. She is usually called Tellus (Mother Earth), although some scholars have named her Pax (Peace), Ceres (goddess of grain), or even Venus. Whoever she is, she epitomizes the fruits of the Pax Augusta. All around her the bountiful earth is in bloom, and animals of different species live peacefully side by side. Personifications of refreshing breezes (note their windblown drapery) flank her. One

176 Chapter 10 T H E RO M A N E M P I R E

1 ft.

rides a bird, the other a sea creature. Earth, sky, and water are all elements of this picture of peace and fertility in the Augustan cosmos.

Processions of the imperial family (FIG. 7-31) and other important dignitaries appear on the long north and south sides of the Ara Pacis. These parallel friezes were clearly inspired to some degree by the Panathenaic procession frieze (FIG. 5-50, bottom) of the Parthenon. Augustus sought to present his new order as a Golden Age equaling that of Athens under Pericles in the mid-fifth century BCE. The emulation of Classical models thus made a political statement as well as an artistic one.

Even so, the Roman procession is very different in character from that on the Greek frieze. On the Parthenon, anonymous figures act out an event that recurred every four years. The frieze stands for all Panathenaic Festival processions. The Ara Pacis depicts a specific event—possibly the inaugural ceremony of 13 BCE when work on the altar began—and recognizable contemporary figures. Among those