Practical Plastic Surgery

.pdf

352 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

in patients with cleft lip and palate. Patients with isolated cleft lip are not believed to have a higher incidence of middle ear disease. If, however, the palate is also clefted then there is a significant risk of inner ear infections due to eustachian tube dysfunction (see chapter on cleft palate repair).

Orthodontic Interventions

The goals of presurgical nasal and alveolar molding are the active molding and repositioning of the nasal cartilages and alveolar processes, and the lengthening of the deficient columella. This method takes advantage of the plasticity of the cartilage in the newborn infant during the first 6 weeks after birth. This high degree of plasticity in neonatal cartilage is due to elevated levels of hyaluronic acid, a component of the proteoglycan intracellular matrix. A description of the protocol for treatment of the patient with bilateral cleft deformity was introduced in 1993 by Grayson, Cutting and Wood. This combined technique has been demonstrated to have a positive influence on the outcome of the primary nasal, labial and alveolar repair.

Repair of Unilateral Cleft Lip

General endotracheal anesthesia with an oral Rae tube is used for all stages of cleft lip repair. A cursory description of a modified Millard operative technique is as follows:

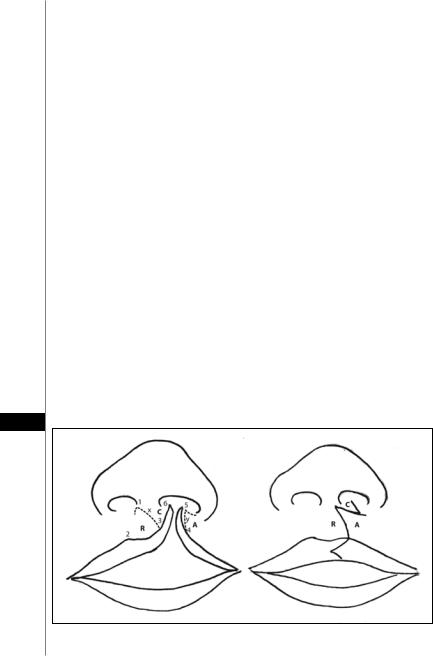

Presurgical Marking (Fig. 58.2)

The key points that are identified and marked are as follows:

•Midline and bases of the columella (1, 6)

•Alar base

•Peak and midpoint of Cupid’s bow on the noncleft side (2, 3)

•Proposed point of Cupid’s bow on the cleft side (4)

Two key elements are involved in the markings: the placement of the final position of the new Cupid’s bow peak and the vertical length of the philtral column to be created on the cleft side. Referring to the diagram, Point 3 is determined as the mirror image of Point 2 based on the distance from the midpoint to the peak of the Cupid’s bow on the noncleft side. The peak on the cleft side, Point 4, is not determined as

58

Figure 58.2. Presurgical marking.

Cleft Lip |

353 |

easily but typically is placed level with Point 2, where the dry vermilion is widest and the white roll above is well developed. The white roll and the dry vermilion taper off medial to this point. It is unreliable to determine the peak on the cleft side, using the distance between the peaks of the Cupid’s bow from the commissure on the noncleft side because of unequal tension of the underlying orbicularis muscle.

Once the anatomic points are marked, draw incision lines that define the five flaps involved in the lip reconstruction. These are the inferior rotation flap (R) of the medial lip element, the medial advancement flap (A) of the lateral lip element, the columellar base flap (C) of the medial lip element, and the two pared mucosal flaps of the medial and lateral lip elements. An additional flap that refines the repair is the vermilion triangular flap to allow for a smoother transition at the vermilion cutaneous junction and at the vermilion contour.

The essential marking is the line that determines the border between the R and C flaps. This line becomes the new philtral column on the cleft side. For the vertical lengths of the philtrum on the cleft side and noncleft side to be symmetric, the length of the rotation advancement flap (y) should equal the vertical length of the philtral column (x) on the noncleft side (distance between alar base and Cupid’s bow peak). For the two lengths, x and y, to be equal, the path of y must be curved as illustrated. In marking the curve, take care to avoid a high arching curve that comes too high at the columellar base to create a generous philtrum, as this significantly diminishes the size of the C flap.

Description of the Repair

After markings, 0.5% lidocaine with epinephrine (1:200,000) is injected into the lip and the nose. In the region of the vermilion-cutaneous junction, incise the muscle for approximately 2-3 mm on either side of the cleft paralleling the vermilion border to allow development of vermilion-cutaneous muscular flaps for final alignment.

Develop the R and C flaps by incising the line (x) between the flaps to allow inferior rotation of the R flap so that it lies horizontally tension free with Point 3, level with Point 2. For this to occur, release must be at all levels (skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, fibrous attachments to the anterior nasal spine, labial mucosa). Cor-

respondingly free the C flap with the medial crus of the alar cartilage and allow it to 58 be repositioned, creating a large gap to be filled by the A flap.

Develop the A flap from the lateral lip element for advancement into the gap between the R and C flaps. In developing the A flap, keep the incision along the alar base at a minimum; it rarely is required to extend much beyond the medial-most aspect of the alar base. A lateral labial mucosal vestibular release is also required to mobilize the A flap medially and to avoid a tight-appearing postoperative upper lip deformity.

As part of the mobilization of the ala, make an incision along the nasal skin-mucosal vestibular junction (infracartilaginous) where the previously developed L flap may be interposed if needed. Widely undermine the nasal tip between the cartilage and the overlying skin approaching laterally from the alar base and medially from the columellar base. While the A flap can be inserted as a mucocutaneous flap incorporating the orbicularis, the author repairs the muscle separately to allow for differential reorientation of its vectors. Dissect the muscle from the overlying skin and the underlying mucosa to accomplish this and divide it into bundles that can be repositioned and interposed appropriately.

Once all the flaps are developed and the medial and lateral lip elements are well mobilized, begin reconstruction. Typically, this begins with creating the labial

354 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

vestibular lining from superior to inferior and then proceeding to the junction of the wet-dry vermilion with completion of the remainder of the vermilion after the cutaneous portion of the lip is completed. At this point, the labial mucosa can be advanced as needed, with additional lengthening and a back cut to allow for adequate eversion of the lip and to avoid a tight-appearing lip postoperatively. Approximation of the muscle bundles must be complete. Appropriately reorient the nasolabial group of muscles toward the nasal spine. Follow this by approximating the orbicularis, interdigitated with its opposing element along the full length of the vertical lip.

Inset the C flap to create a symmetric columellar length and flare at its base. Millard originally described the C flap to cross the nasal sill to insert into the lateral lip element as a lateral rotation-advancement flap. Millard later refined the C flap as a medial superior rotation flap to insert into the medial lip element, augmenting the columellar height and creating a more natural flare at the base of the medial footplate. The latter method occasionally results in a nexus of scars at the base of the columellar with unfavorable healing if the flaps are not well planned. However, the author continues to use the C flap in either position as needed. Set the ala base in place. As the C and A flaps and the ala are inset, take care to leave an appropriate width to the nasal sill to avoid a constricted-appearing nostril, which is nearly impossible to correct as a secondary deformity.

Approximate the vermilion-cutaneous junction and inset the vermilion mucocutaneous triangular flap. Use dermal sutures to approximate the skin edges. Final approximation is with nylon sutures, ideally removed at 5 days. If the cutaneous edges are well approximated with dermal sutures alone, one may occasionally use a cyanoacrylate-type adhesive. Reposition the cleft alar cartilage with suspension/transfixion sutures and a stent. Further shape the ala with through-and-through absorbable sutures as needed.

Repair of Bilateral Cleft Lip

Originating on either side of the columellar base, vertical lines are marked ending in a triangular base such that Cupid’s bow is 6 to 8 mm wide. Lateral forked flaps are also outlined prior to making the skin incisions. All philtral-based flaps are elevated

58from the surrounding vermilion. The prolabial mucosal vermilion complex is thinned before being sutured together, creating the midline posterior labial sulcus.

The lateral lip segments are incised vertically down from the medial alar base, analogous to the originally made prolabial incisions. Medially-based buccal mucosal flaps are rotated from the alar base horizontally. The alar cartilages are freed via an intercartilaginous incision, originating from the piriform aperture, and secured together at the domes and to the upper lateral cartilages. The buccal mucosal flaps are then sutured into the inferior intercartilaginous incision to increase length for the nasal floor reconstruction. The mucosal orbicularis flaps are sutured together to create the anterior labial sulcus, with the most superior suture secured to the nasal spine to prevent inferior displacement. Finally, the inferior white roll-vermilion-mucosal flaps are apposed to create Cupid’s bow and tubercle complex.

Postoperative Considerations

For the child who is breastfed, the author encourages uninterrupted breastfeeding after surgery. Some centers will allow bottle-fed children to resume feedings immediately following surgery with the same crosscut nipple used before surgery, while others have the child use a soft catheter-tip syringe for 10 days and then resume normal nipple bottle feeding.

Cleft Lip |

355 |

The author uses velcro elbow immobilizers on the patient for 10 days to minimize the risk of the child inadvertently injuring the lip repair. The parents are instructed to remove the immobilizers from alternate arms several times a day in a supervised setting. For the child with sutures, lip care consists of gently cleansing suture lines using cotton swabs with diluted hydrogen peroxide and liberal application of topical antibiotic ointment several times a day. This is continued for 10 days. If cyanoacrylate adhesive is used, no additional care is required in the immediate postoperative period until the adhesive film comes off. The parents are told to expect scar contracture, erythema and firmness for the first 4-6 weeks postoperatively, and that this gradually begins to improve 3 months after the procedure. Typically, parents are also instructed to massage the upper lip during this phase and to avoid placing the child in direct sunlight until the scar matures.

Pearls and Pitfalls

There is no agreement on the ideal timing and the technique of the repair. It is important for the surgeon to view the various repairs as principles of repair—a guideline to be followed, not a rigid design to which the surgeon must strictly adhere. Cleft lip repair is one of the few procedures that has a lot of room for modifications and innovations on the part of the surgeon.

Occasionally, an additional 1- to 2-mm back cut just medial to the noncleft philtral column is required along with a mucosal back cut to allow for adequate inferior rotation of the rotation (R) flap.

The current trend in cleft surgery is toward a more aggressive mobilization and repositioning of the lower lateral cartilages of the nose as an integral part of the cleft lip repair.

It is important to recall that the maxillary alveolar arches typically are at different heights in the coronal plane, and the ala must be released completely and mobilized superomedially to achieve symmetry, although ultimately its maxillary support is inadequate until arch alignment and bone grafting can be accomplished.

After approximation of the vermilion-cutaneous junction and inset of the vermilion mucocutaneous triangular flap, the lip may appear to be vertically short.

One solution is to inset a small, 2- to 3-mm triangular flap into the medial lip just 58 above the vermilion.

Suggested Reading

1.Afifi GY, Hardesty RA. Bilateral cleft lip. Plastic Surgery, Indications, Operations and Outcomes. St. Louis: Mosby, 2000:769-797.

2.Byrd HS. Unilateral cleft lip. Grabb and Smith Plastic Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1997:245-253.

3.Cutting CB. Primary bilateral cleft lip and nose repair. Grabb and Smith Plastic Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1997:255-262.

4.Grayson BH, Santiago PE. Presurgical orthopedics for cleft lip and palate. Grabb and Smith Plastic Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1997:237-244.

5.Kernahan DA. On cleft lip and palate classification. Plast Reconstr Surg 1973; 51:578.

6.LaRossa D. Unilateral cleft lip repair. Plastic Surgery, Indications, Operations and Outcomes. St. Louis: Mosby, 2000:755-767.

7.LaRossa D, Donath G. Primary nasoplasty in unilateral and bilateral cleft lip nasal deformity. Clin Plast Surg 1993; 29(4):781.

8.Mulliken JB. Primary repair of the bilateral cleft lip and nasal deformity. In: Georgiade GS, ed. Plastic, Maxillofacial and Reconstructive Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins, 1997.

9.Salyer KF. Primary correction of the unilateral cleft lip nose: A 15-years experience. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986; 77:558.

Chapter 59

Cleft Palate

Alex Margulis

Introduction

A cleft palate has tremendous aesthetic and functional implications for patients in their social interactions, particularly on their ability to communicate effectively and on their facial appearance. The treatment plan focuses on two areas: speech development and facial growth. Speech development is paramount in the appropriate management of cleft palate. Many surgical techniques and modifications have been advocated to improve functional outcome and aesthetic results. The most controversial issues in the management of cleft palate are the timing of surgical intervention, speech development after various surgical procedures and the effects of surgery on facial growth.

Classification

Numerous classifications have been suggested over the years. The most common classification scheme is that of Kernahan (Fig. 59.1). This “striped Y” classification has been almost universally adopted for its simplicity and usefulness. A modification of the Kernahan classification was introduced several years ago by Smith et al and it uses an alphanumeric system to describe all cleft varieties.

Embryology

The embryogenesis of the palate has two separate phases: the formation of the primary palate followed by the formation of the secondary palate. Palatal development begins at approximately day 35 of gestation with the emergence of facial processes. In formation of the primary palate, the fusion of the medial nasal process (MNP) with the maxillary process (MxP) is followed by the lateral nasal process (LNP) fusing with the MNP. Failure of fusion or breakdown of fusion of the processes results in a cleft of the primary palate. The genesis of the secondary palate begins at the completion of primary palate formation. The secondary palate arises from the bilateral shelves that develop from the medial aspect of the MxP. The two shelves meet in the midline, and the fusion process begins as the shelves move superiorly. Interference in the fusion leads to clefting of the secondary palate.

Incidence

The incidence of cleft lip/palate (CL/P) by race is 2.1/1000 in Asians, 1/1000 in whites and 0.41/1000 in blacks. Isolated cleft palate shows a relatively constant ratio of 0.45-0.5/1000 births. The foremost type of clefting is a bifid uvula, occurring in 2% of the population. The second most frequent type is a left unilateral complete cleft of the palate and prepalatal structures. Midline clefts of the soft palate and parts of the hard palate are also common. Complete clefts of the secondary palate are twice as common in females as in males while the reverse is true of velar clefts. About

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.

Cleft Palate |

357 |

|

|

|

|

7-13% of patients with isolated cleft lip and 11–14% of patients with CL/P have other anomalies at birth.

Inheritance Patterns

In 25% of patients, there is a family history of facial clefting, which does not follow either a normal recessive or dominant pattern. The occurrence of clefting deformities do not correspond to any Mendelian pattern of inheritance, and it would appear that clefting is inherited heterogeneously. This observation is supported by evidence from studies of twins that indicate the relative roles of genetic and nongenetic influences of cleft development. For isolated cleft palate and combined CL/P, if the proband has no other affected firstor second-degree relatives, the empiric risk of a sibling being born with a similar malformation is 3-5%. However, if a proband with a combined CL/P has other affected first-degree relatives, the risk for siblings or subsequent offspring is 10-20%.

Etiology

The causes of cleft palate appear to be multifactorial. Some instances of clefting may be due to an overall reduction in the volume of the facial mesenchyme, which leads to clefting by virtue of failure of mesodermal penetration. In some patients, clefting appears to be associated with increased facial width, either alone or in association with encephalocele, idiopathic hypertelorism, or the presence of a teratoma. The characteristic U-shaped cleft of the Pierre Robin anomaly is thought to be dependent upon a persistent high position of the tongue, perhaps associated with a failure or delay of neck extension. This prevents descent of the tongue, which in turn prevents elevation and a medial growth of the palatal shelves.

The production of clefts of the secondary palate in experimental animals has frequently been accomplished with several teratogenic drugs. Agents commonly used are steroids, anticonvulsants, diazepam and aminopterin. Phenytoin and diazepam may also be causative factors in clefting in humans. Infections during the first trimester of pregnancy, such as rubella or toxoplasmosis, have been associated with clefting.

Clinical Findings

The pathologic sequelae of cleft palate can include airway issues, feeding and nutritional difficulties, abnormal speech development, recurrent ear infections, hear- 59 ing loss and facial growth distortion.

Airway Problems

The infant with Pierre Robin sequence or other conditions in which the cleft palate is observed in association with a micrognathia or retrognathic mandible may be particularly prone to upper airway obstruction. Prone positioning is the initial step in management.

Feeding Difficulty

The communication between the oral and nasal chamber impairs the normal sucking and swallowing mechanism of the cleft infants. Food particles can reflux into the nasal chamber. Although a child with cleft palate may make sucking movements with the mouth, the cleft prevents the child from developing adequate suction. However, in general swallowing mechanisms are normal. Therefore, if the milk or formula can be delivered to the back of the child’s throat, the infant feeds effectively. Breastfeeding is usually not successful unless milk production is abundant.

358 Practical Plastic Surgery

Speech Abnormalities

Speech abnormalities are intrinsic to the anatomic derangement of cleft palate. The facial growth distortion appears to be, to a great extent, secondary to surgical interventions. An intact velopharyngeal mechanism is essential in production of nonnasal sounds and is a modulator of the airflow in the production of other phonemes that require nasal coupling. The complex and delicate anatomic manipulation of the velopharyngeal mechanism, if not successfully learned during early speech development, can permanently impair normal speech acquisition.

Middle Ear Disease

The disturbance in anatomy associated with cleft palate affects the function of the eustachian tube orifices. Parents and physicians should be aware of the increased possibility of middle ear infection so that the child receives treatment promptly if symptoms arise. The abnormal insertion of the tensor veli palati prevents satisfactory emptying of the middle ear. Recurrent ear infections have been implicated in the hearing loss of patients with cleft palate. The hearing loss may worsen the speech pathology in these patients. Evidence that repair of the cleft palate decreases the incidence of middle ear effusions is inconsistent. However, these problems are overshadowed by the magnitude of the speech and facial growth problems.

|

Facial Growth Abnormalities |

|

|

Multiple studies have demonstrated that the cleft palate maxilla has some intrin- |

|

|

sic deficiency of growth potential. This intrinsic growth potential deficiency varies |

|

|

from isolated cleft of the palate to complete CL/P. This growth potential is further |

|

|

impaired by surgical repair. Any surgical intervention performed prior to comple- |

|

|

tion of full facial growth can have deleterious effects on maxillary growth. Disagree- |

|

|

ment exists as to the appropriate timing of surgery to minimize the harmful effects |

|

|

on facial growth and on what type of surgical intervention is most responsible for |

|

|

growth impairment. The formation of scar and scar contracture in the areas of de- |

|

|

nuded palatal bones are most frequently blamed for restriction of maxillary expan- |

|

|

sion. The growth disturbance is exhibited most prominently in the prognathic |

|

|

appearance during the second decade of life despite the normal appearance in early |

|

|

childhood. The discrepant occlusion relationship between the maxilla and the man- |

|

59 |

||

dible is usually not amenable to nonsurgical correction. |

||

|

Associated Deformities

The surgeon must always keep in mind that in as many as 29% of patients, the child with cleft palate may have other anomalies. These may be more commonly associated with isolated cleft palate than with CL/P. High among the associated anomalies are those affecting the circulatory and skeletal systems.

Surgical Goals and the Benefits of Repair

The broad goal of cleft palate treatment is to separate the oral and nasal cavities. Although this is not absolutely necessary for feeding, it is advantageous to normalize feeding and decrease regurgitation and nasal irritation. More important than repairing the oral and nasal mucosa is the repositioning of the soft palate musculature to anatomically recreate the palate and to establish normal speech. Another goal of palate repair is to minimize restriction of growth of the maxilla in both sagittal and transverse dimensions.

Cleft Palate |

359 |

|

|

|

|

Palate repair with repositioning of the palatal musculature may be advantageous to eustachian tube function and ultimately to hearing. Because the levator and the tensor veli palatini have their origins along the eustachian tube, repositioning improves function of these muscles, improves ventilation of the middle ear and decreases serous otitis, which further decreases the incidence of hearing abnormality. Palate repair alone does not usually completely correct this dysfunction and additional therapy frequently includes placement of ear tubes as necessary.

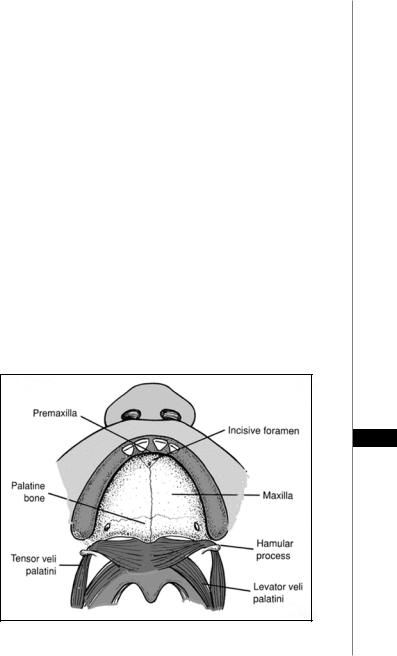

Relevant Anatomy

The bony portion of the palate is a symmetric structure divided into the primary and secondary palate based on its embryonic origin (Fig. 59.1). The premaxilla, alveolus and lip, which are anterior to the incisive foramen, are parts of the primary palate. Structures posterior to it, which include the paired maxilla, palatine bones and pterygoid plates, are part of the secondary palate. The severity of the clefting of the bony palate varies from simple notching of the hard palate to complete clefting of the alveolus. The palatine bone is located posterior to the maxilla and pterygoid lamina. It is composed of horizontal and pyramidal processes. The horizontal process contributes to the posterior aspect of the hard palate and becomes the floor of the choana. The pyramidal process extends vertically to contribute to the floor of the orbit.

Even though the bony defect is important in the surgical treatment of cleft palate, the pathology in the muscles and soft tissues has the greatest impact on the functional result. Six muscles have attachment to the palate: levator veli palatini, superior pharyngeal constrictor, musculus uvulae, palatopharyngeus, palatoglossus and tensor veli palatini. The three muscles that appear to have the greatest contribution to the velopharyngeal function are the musculus uvulae, levator veli palatini and superior pharyngeal constrictor.

59

Figure 59.1. Anatomy of the palate. (Reprinted from emedicine.com with permission.)

360 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

The musculus uvulae muscle acts by increasing the bulk of the velum during muscular contraction. The levator veli palatini pulls the velum superiorly and posteriorly to appose the velum against the posterior pharyngeal wall. The medial movement of the pharyngeal wall, attributed to the superior pharyngeal constrictor, aids in the opposition of the velum against the posterior pharyngeal wall to form the competent sphincter. The palatopharyngeus displaces the palate downwards and medially. The palatoglossus is mainly a palatal depressor that plays a role in the production of phonemes with nasal coupling by allowing controlled airflow into the nasal chamber. The tensor veli palatini does not contribute to the movement of the velum. The tensor veli palatini’s tendons hook around the hamulus of the pterygoid plates and the aponeurosis of the muscle inserts along the posterior border of the hard palate. The muscle originates partially on the cartilaginous border of the auditory tubes. The function of the tensor veli palatini, similar to the tensor tympani with which it shares its innervation, is to improve the ventilation and drainage of the auditory tubes.

In a cleft palate, the aponeurosis of the tensor veli palatini, instead of attaching along the posterior border of the hard palate, is attached along the bony cleft edges. All the muscles that attach to the palate insert onto the aponeurosis of this muscle. Thus, the overall length of the palate is shortened. The abnormality in the tensor veli palatini increases the incidence of middle ear effusion and middle ear infection. The muscle sling of the levator veli palatini is also interrupted by the cleft palate. The levator does not form the complete sling. The medial portion of each side attaches to the medial edge of the hard palate. Thus, in patients with cleft palate, the effectiveness of the velar pull against the posterior pharyngeal wall is impaired. Of the six muscles, the prevailing theory attributes most of the contribution to the velopharyngeal competence to the levator veli palatini.

Relative Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications for the repair of cleft palate. Relative contraindications include concurrent illness or other medical condition that can interfere with general anesthesia, possible compromise of the airway in a child with a preexisting airway problem (such as severe micrognathia), severe developmental

59 delay, or a short life expectancy because of other severe illnesses.

Preoperative Considerations

Lab Studies

•Routine lab studies are noncontributory in otherwise healthy infants with cleft palate. Some centers obtain a blood count as a routine study before performing surgery on a child with cleft palate. The author does not find this necessary unless some other associated medical condition coexists.

Imaging Studies

•Routine imaging studies are noncontributory in otherwise healthy infants who undergo primary cleft palate repair.

Diagnostic Procedures

•Early collaboration with an audiologist and an otolaryngologist, including examination and early audiologic assessment, can prevent long-term hearing deficits.

Cleft Palate |

361 |

|

|

|

|

Orthodontic Intervention

The available data suggest that to optimize speech development some degree of facial growth distortion may need to be accepted. One role of orthodontic intervention is to minimize the severity of the growth disturbance. Interventions vary according to the type of cleft. Many types of orthodontic appliances have been used in the treatment of cleft palate patients. In CL/P, orthodontic appliances can be used to realign the premaxilla into a normal position prior to lip closure. Orthodontic interventions in patients with cleft palate are frequently aimed at maxillary arch expansion, correction of malocclusion and correction of a developing class III skeletal growth pattern. The maxillary dental arch contracture may become significant, requiring the surgical repair of the hard palate.

Orthodontic interventions may be started early or delayed for several years. When orthodontic manipulation is initiated early, difficulties may occur. Maintaining orthodontic appliances in the infant population may present a challenge unless these appliances are fixed in position. The benefit of these orthodontic interventions has also been questioned, especially in patients with isolated cleft palate. The most beneficial period for orthodontic interventions in isolated cleft palate may be during the mixed dentition period.

At the age of 6-8 years, the permanent incisors begin erupting. At this age, the presence of grossly misaligned teeth and severe malocclusion can lead to social isolation. The incisor relation can be corrected and maintained with relatively simple interventions. Patients who undergo palatal arch expansion during this period can benefit from the rapid growth phase. The orthodontic intervention can also proceed with more cooperation from the patient in this age group. Orthodontic management of arch deformities after the permanent dentition has erupted is more limited. The established malocclusion and asymmetry between the maxillary arch and mandibular arch usually require orthognathic surgery.

Surgical Therapy

Timing of Palatal Closure

The timing of cleft palate closure remains controversial. The goals of palatal repair include normal speech, normal palatal and facial growth and normal dental occlusion. Early palate repair is associated with better speech results, but early repair 59 also tends to produce severe dentofacial deformities. Several studies have consistently shown that children whose palates were repaired at an earlier age appeared to

have better speech and needed fewer secondary pharyngoplasties compared to those whose surgery had been delayed beyond the first 12 months of life.

Noordhoff and associates found that children undergoing delayed palatoplasty for cleft palate had significantly poorer articulation skills before the hard palate closure compared to children of the same age who did not have clefts. These benefits of early cleft palate repair, from the standpoint of speech and hearing, must be weighed against the increased technical difficulty of performing the procedure at a younger age and possible adverse effects on maxillary growth. Numerous studies failed to demonstrate an observable difference in underdevelopment of the palatal arch among children undergoing operations at various ages. The surgical intervention appears to interfere with midfacial growth without regard to the age of the patient at the time of repair.

Bifid uvula occurs in 2% of the population. Although this can occur in association with a submucous cleft palate, most infants with bifid uvula do not have this