Practical Plastic Surgery

.pdf

192 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Pearls and Pitfalls

•Most surface contours of the nose are either flat (such as the dorsum) or convex (such as the alae). Reconstruction of flat surfaces is best done with a skin graft that contracts in a linear fashion, whereas convex surfaces should be reconstructed with a flap that contracts in a spherical manner.

•When designing a flap for nasal reconstruction, for example the forehead flap, it is critical to account for loss of flap length that results from the arc of rotation. A Raytek® sponge can be used to determine the designed length of the flap. By holding one end of the sponge over the base of the flap and rotating the other end into the defect, the amount of extra length needed to overcome the arc of rotation can be determined.

•There are exceptions to the rule of replacing “like with like” tissue. For example, the alar rims normally have a convex shape even though they do not contain cartilage. However, their convexity can best be restored using cartilaginous support.

Suggested Reading

1.Burget GC, Menick FJ. The subunit principle in nasal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1985; 76(2):239.

2.Burget GC, Menick FJ. Nasal reconstruction: Seeking a fourth dimension. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986; 78(2):145.

3.Menick FJ. Artistry in aesthetic surgery. Aesthetic perception and the subunit principle. Clin Plast Surg 1987; 14(4):723.

4.Millard Jr DR. Aesthetic reconstructive rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg 1981; 8(2):169.

5.Singh DJ, Bartlett SP. Aesthetic considerations in nasal reconstruction and the role of modified nasal subunits. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003; 111(2):639.

32

Chapter 33

Lip Reconstruction

Amir H. Taghinia, Edgar S. Macias, Dzifa S. Kpodzo and Bohdan Pomahac

Introduction

The lips are not only a major aesthetic component of the face, but are also important for facial expression, speech and eating. Goals in lip reconstruction are to restore normal anatomy, oral competence and contour. These goals are easily attained following repair of small lip defects. However, restoring these characteristics of the lips in large defects remains a more arduous task. Although many different methods of lip reconstruction have been described in the literature, a few of the important and more commonly utilized methods are outlined in this chapter.

Anatomy

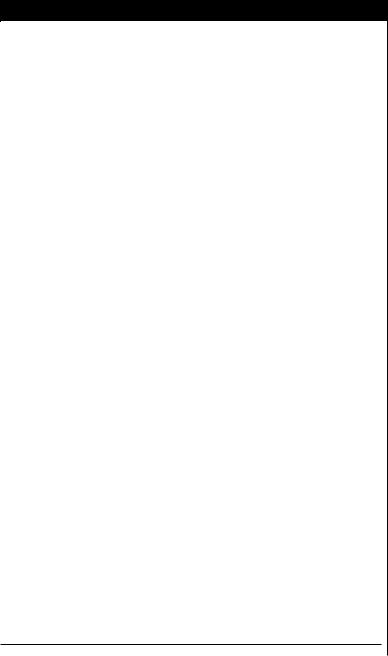

The subunits of the surgical upper and lower lips are shown in Figure 33.1. The surgical upper lip includes the entire area from one nasolabial fold to the other, and all structures down to the oral orifice. It extends intraorally to the upper gingivolabial sulcus. It is divided into the vermilion, one central and two lateral aesthetic subunits. The lower lip includes all structures superior to the labiomental fold including the vermilion and continuing intraorally to the inferior gingivolabial sulcus.

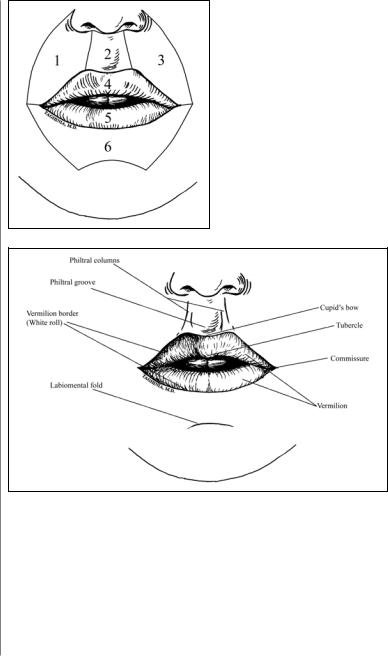

Extending from the nasal base are bilateral philtral columns flanking the centrally located philtrum (Fig. 33.2). The philtral columns extend downward to meet the vermilion-cutaneous junction (also known as the ‘white roll’) of the upper lip. Cupid’s bow is the portion of the vermilion-cutaneous junction located at the base of the philtrum. The tubercle is the fleshy middle part of the upper lip from which the vermilion extends bilaterally to meet the commissures. The vermilion of the lower lip is bisected by the central sulcus which is prominent in some individuals. The lower lip is considered less anatomically complex than the upper lip because it lacks a definitive central structure.

The vermilion is made of a modified mucosa with submucous tissue and orbicularis oris muscle underneath. The large number of sensory fibers per unit of vermilion is reflected in its comprising a disproportionately large part of the cerebral cortex. It has a high degree of sensitivity to temperature, light touch and pain. The natural lines of the vermilion are vertical, thus scars on the vermilion should be placed vertically if possible.

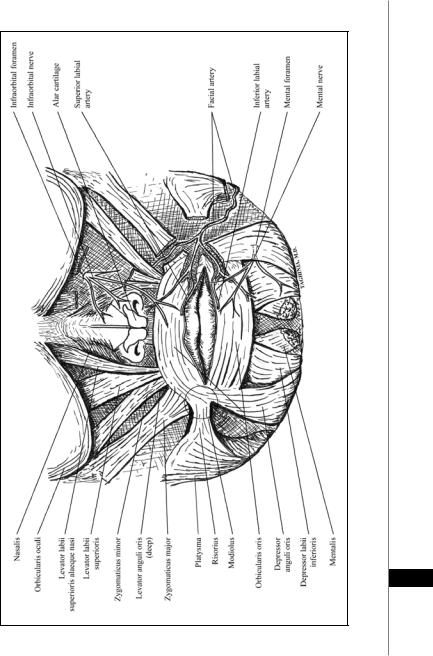

The muscular anatomy of the lips is shown in Figure 33.3. The primary muscle responsible for oral competence is the orbicularis oris muscle. This muscle functions as a sphincter, puckering and compressing the lips. The fibers of the orbicularis oris muscle extend to both commissures and converge with other facial muscles just lateral to the commissures at the modiolus. The major elevators of the upper lip are the levator labii superioris, levator anguli oris and the zygomaticus major.

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.

194 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Figure 33.1. Subunits of the surgical upper and lower lips. The nasolabial folds on either side comprise the lateral borders of the upper and lower lips. The upper lip is made of the upper vermilion (4), two lateral subunits (1,3) and one central subunit (2) and the philtrum. These subunits are separated by the philtral columns and the white roll. The lower lip is made of the lower vermilion (6) and a large central unit that ends inferiorly at the labiomental fold.

|

Figure 33.2. Topographic anatomy of the lips. |

|

|

The mentalis muscle elevates and protrudes the middle portion of the lower lip. |

|

|

The major depressors of the lips are the depressor labii inferioris and depressor |

|

|

anguli oris. The risorius muscle pulls the commissures laterally. |

|

33 |

||

The blood supply to the lips comes from the superior and inferior labial arteries, |

||

|

which in turn are branches of the facial arteries (Fig. 33.3). The paired superior and |

|

|

inferior labial arteries form a rich network of collateral blood vessels, thus providing |

|

|

a dual blood supply to each lip. These vessels lie between the orbicularis oris and the |

|

|

buccal mucosa near the transition from vermilion to buccal mucosa. There are no |

|

|

specific veins; instead there are several draining tributaries that eventually coalesce |

Lip Reconstruction |

195 |

Figure 33.3. Anatomy of the perioral facial muscles. The facial nerve is not shown. See text for details.

33

196 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

into the facial veins. The lymphatic channels of the upper lip and lateral lower lip drain into the submandibular nodes; whereas, the central lower lip lymphatics drain into the submental nodes.

Motor innervation of the perioral muscles is from facial nerve branches. The buccal branches of this nerve supply motor input into the lip elevators; whereas, the marginal mandibular branches supply the lip depressors. The motor nerve enters each individual muscle on its posterior surface. Sensory supply to the upper lip comes from the infraorbital nerve (second trigeminal branch) and the lower lip is supplied by the mental nerve (third trigeminal branch).

Primary Closure

Lip lesions are typically due to trauma, infection, or tumors. Defects less than one-fourth to one-third of the total lip length can be closed primarily. This involves the apposition of the lateral margins of the wound on both sides and direct layered closure. The muscle is approximated with interrupted deep absorbable sutures. The white roll is closely approximated and then the labial mucosa and vermilion are closed. Finally, the skin is closed with fine nonabsorbable sutures.

Ideally, primary closure should cause minimal aesthetic and functional deformity; however, it can sometimes result in reduction of the oral aperture as well as asymmetry of the involved lip. Furthermore, primary closure in the upper lip can be problematic because opposing the edges of a large wound may create unfavorable distortion of the philtrum.

Vermilion Reconstruction

The vermilion spans the entire length of the oral aperture, becoming increasingly narrow and tapering laterally as it approaches the commissure on both sides. It forms the transition zone between skin and mucosa of the inner mouth. Defects involving the vermilion can range from superficial, such as leukoplakia in which there is limited compromise of the integument, to significant, in which tissue deficit extends to deeper muscle and mucosal tissue. Although small defects of the vermilion can be primarily closed or left alone to heal by secondary intention, larger defects require reconstruction.

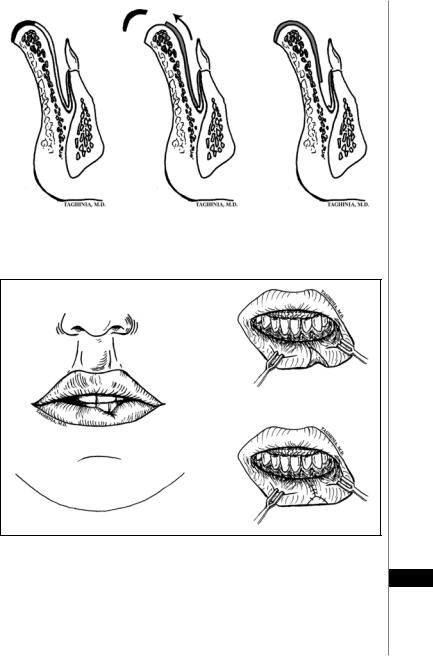

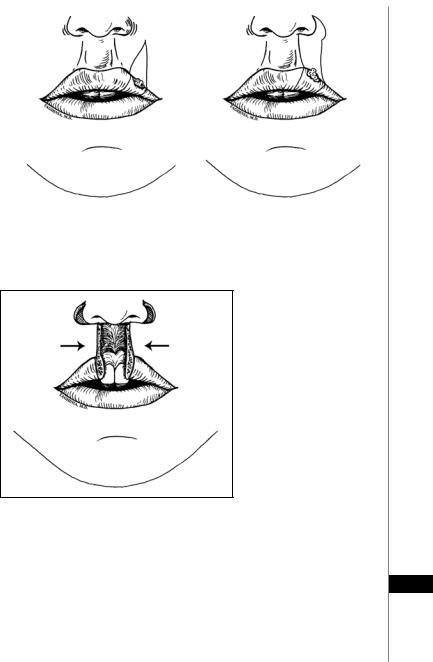

Precise alignment of the vermilion-cutaneous margin on both sides ensures a curvilinear appearance of the border and avoids step-offs or lip notches after healing. The traditional labial mucosal advancement flap can replace vermilion resections that span the entire length of the lower lip. The mucosa on the buccal surface of the lower lip is undermined and advanced to the previous mucocutaneous junction. Maximal use of blunt undermining helps to preserve sensory innervation of this vermilion-to-be. Additional advancement can be achieved using a transverse incision in the gingivobuccal sulcus and in the process creating a bipedicled mucosa flap based laterally (Fig. 33.4). Extensive flap mobilization usually results in an insensate flap.

A notched appearance of the vermilion can result from scar contractures or ver-

33milion volume deficiency (due to previous surgery or trauma). Scar contractures can be released with a Z-plasty. This procedure recruits vermilion tissue on either side of the scar to functionally lengthen the scar in the antero-posterior and supero-inferior direction. A notched appearance due to volume deficiency can be corrected with a local musculomucosal V-Y advancement flap (Fig. 33.5).

Lip Reconstruction |

197 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 33.4. Vermilion reconstruction using labial mucosal advancement flap— cross-sectional view.

Figure 33.5. Repair of lower lip vermilion notch using V-Y advancement flap.

The next option of donor tissue is a flap from the ventral surface of the tongue 33 but it is less than ideal because of color mismatch. Pribaz described the facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap, which is a based on the facial artery and is used to reconstruct defects involving vermilion, lip, palate and a host of other oral structures. Labia minora grafts can also be used to reconstruct the vermilion.

198 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Commissure Reconstruction

Commissure deformities often result from electrical burns, trauma, or reconstructive lip surgery. For post-burn commissure contractures, splinting techniques have reduced the need for surgical correction. Nevertheless, repairing deformities that do not respond to conservative measures remains complex. The intricate network of adjoining perioral muscle fibers at the modiolus (which is crucial for oral competence and facial animation) is nearly impossible to reconstruct. Furthermore, the contralateral commissure is the gold standard of comparison when evaluating the results of a unilateral reconstruction, thus leaving little room for discrepancy. Various approaches attempt to repair mucosal defects involving the commissure including the simple rhomboid flap, in which intraoral mucosa is advanced to reconstruct the commissure angles after an incision is made to widen the commissure laterally. The tongue flap also may be used when the mucosal defect is thick in the region of the commissure. Despite many proposed techniques, commissure reconstruction remains a difficult task and attempts at reconstruction often yield poor results.

Upper Lip Reconstruction

Upper lip cancers are usually basal cell carcinomas that spare the vermilion. The central aesthetic subunit of the upper lip, the philtrum, makes upper lip reconstruction more challenging than lower lip reconstruction. Upper lip defects can be divided into partial-thickness and full-thickness defects.

Partial-thickness Defects

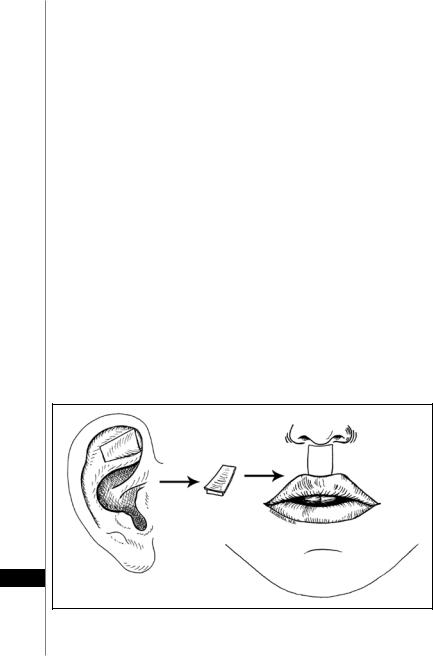

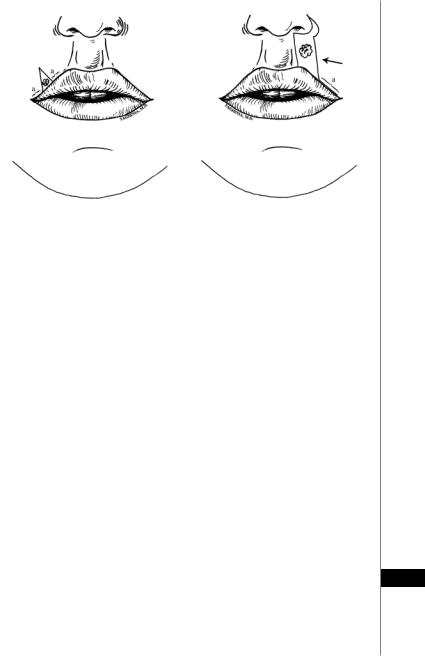

Partial-thickness philtral defects can be allowed to heal by secondary intention or skin grafting. The triangular fossa skin-cartilage composite graft is well-described for reconstructing the philtrum in burn patients (Fig. 33.6). Partial-thickness defects of the lateral subunits can be repaired by a variety of means (Fig. 33.7). For larger lateral subunit defects, an inferiorly-based nasolabial flap may be employed (sometimes to replace the entire lateral subunit). Upper lip defects that are next to

33

Figure 33.6. Conchal skin-cartilage composite graft to repair the philtrum in burn patients.

Lip Reconstruction |

199 |

|

|

|

|

A |

B |

|

|

|

|

Figure 33.7. Repair of partial-thickness upper lip defects. In (A) the lesion is excised as a partial-thickness wedge. Lateral incisions along the white roll (a) allow the edges of the wound to be closed primarily. In (B) the lesion is excised as a partial-thickness section that incorporates a perialar crescent. A similar incision along the white roll (a) and undermining of the lateral flap allows the edges of the wound to come together.

the nasal ala may also be reconstructed with the nasolabial flap (Fig. 33.8A,B). This reconstructive method may not be ideal in men, however, because the nasolabial flap is not hair-bearing. Primary closure may be achieved for men by advancing adjacent lip and cheek tissue (Fig. 33.8C).

Full-Thickness Defects

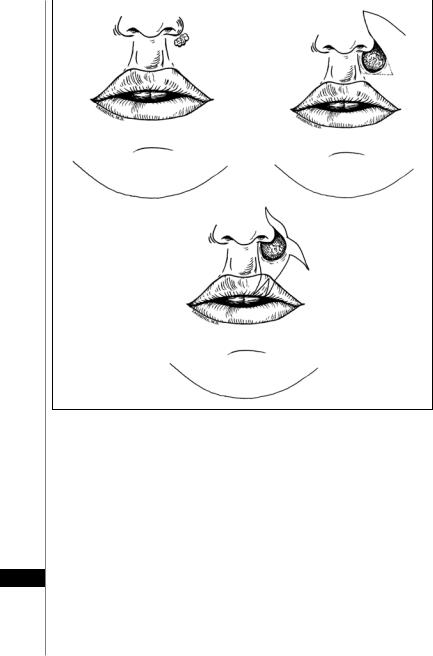

For full-thickness defects, the choice of reconstructive option depends on the size of the defect. Defects of one-quarter to one-third of the upper lip can be closed primarily (Fig. 33.9). Larger defects of the upper lip require flaps from the lower lip or recruitment of adjacent cheek tissue. If these larger defects involve the central portion of the upper lip, perialar crescentic excisions may provide additional mobility if needed (Fig. 33.10).

Defects measuring one-third to two-thirds of the upper lip may be closed with the Abbe flap, the Karapandzic flap, or the Estlander flap (see below for description of each method; also see Figs. 33.12-33.15). The Abbe and Karapandzic flaps are used for central defects whereas, the Estlander flap is used for lateral defects that involve the commissure. The Abbe flap may also be used for lateral defects that do not involve the commissure.

Defects greater than two-thirds of the upper lip can be closed with the Bernard-Burow’s technique if sufficient cheek tissue is available (Fig. 33.17). How- 33 ever, if sufficient cheek tissue is not available, most surgeons choose a free flap for reconstruction. The aforementioned reconstructive methods are described later in

this chapter. Often, these methods can also be applied to closure of lower lip defects as well. Accordingly, for simplicity and ease of explanation, reference is often made to lower lip reconstruction.

200 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

A |

B |

C

Figure 33.8. Repair of partial-thickness upper lip defects. The lesion (A) is excised leaving a circular partial-thickness defect. The defect can be closed with an inferiorly-based nasolabial flap (B) or using advanced tissue from the cheek and lip (C). The nasolabial flap is less ideal in men because the flap is not hair-bearing.

Lower Lip Reconstruction

In contrast to the upper lip, lower lip reconstruction tends to be simpler. This advantage is due to the greater laxity of the soft tissues and lack of a separate central aesthetic unit. Since oral competence is mainly mediated by the lower lip, function and sensation tends to be more important than aesthetics.

33 Partial-Thickness Defects

Partial-thickness defects of the lower lip are treated differently based on whether the defect involves skin and subcutaneous tissue or vermilion. Skin and subcutaneous defects of the lower lip subunit can be left to heal by secondary intention or skin grafted. More commonly, however, a local advancement flap, rotation flap or transposition flap is employed for reconstruction. Careful planning and

Lip Reconstruction |

201 |

|

|

|

|

A |

B |

|

|

|

|

Figure 33.9. Full-thickness excisions of the upper lip. Defects up to one-third of the upper lip can be excised and closed primarily. Lateral defects often require wedge excision (A); whereas, defects that are closer to the philtrum can be excised with the help of perialar crescentic excisions for additional mobility (B).

Figure 33.10. Perialar crescentic partial-thickness excisions for primary closure of full-thickness upper lip defects.

execution should allow the final scars to lie parallel to the natural skin tension lines. As previously mentioned, the white roll should be realigned as closely as possible.

Full-Thickness Defects

Many of the reconstructive methods used for upper lip reconstruction can also 33 be used for lower lip reconstruction. As in the upper lip, reconstructive options for full-thickness defects depend on the size of the defect. Defects up to one-third of the lower lip can be closed primarily as described earlier (Fig. 33.11). Larger defects measuring one-third to two-thirds of the lower lip width may be closed with the Karapandzic, Abbe or Estlander flaps (see below).