Economics_-_New_Ways_of_Thinking

.pdf

Chapter Summary

Be sure you know and remember the following key points from the chapter sections.

Section 1

Transaction costs—the time and effort required in an exchange—are high in a barter economy.

Money is any good that is widely accepted in exchange and in repayment of debts.

The value of money comes from its general acceptability in exchange.

Money has three major functions: a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value.

Early bankers were goldsmiths who gave the customers a warehouse receipt for the gold they stored with the goldsmith.

Section 2

The most basic money supply in the United States is called M1 (M-one).

M1 consists of currency, checking accounts, and traveler’s checks.

Currency is coins and paper money, or Federal Reserve notes.

Checking accounts are also known as demand deposits, money deposited that can be withdrawn by writing a check.

A traveler’s check is issued by a bank in specific denominations and sold to travelers for their use.

A savings account is considered near-money.

Credit cards are not money because they cannot be used as repayment of debt.

Section 3

As a central bank, the Federal Reserve System is the chief monetary authority in the country.

The Federal Reserve’s main activities include the following: control the money supply, supply the economy with paper money, hold bank reserves, provide check-clearing services, supervise member banks, and act as lender of last resort.

Economics Vocabulary

To reinforce your knowledge of the key terms in this chapter, fill in the following blanks on a separate piece of paper with the appropriate word or phrase.

1.A(n) ______ is an economy in which trades are made in terms of goods and services instead of money.

2.Anything that is generally accepted in exchange for goods and services is a(n) ______.

3.A banking arrangement in which banks hold only a fraction of their deposits and lend out the remainder is referred to as ______.

4.The ______ is composed of currency, checking accounts, and traveler’s checks.

5.When the Fed buys or sells government securities, it is conducting a(n) ______.

6.The governing body of the Federal Reserve System is the ______.

7.Total reserves minus required reserves equals

______.

8.______ are the minimum amount of reserves a bank must hold against its checking account deposits, as mandated by the Fed.

9.The interest rate that one bank charges another bank for a loan is called the ______.

10.The interest rate that the Fed charges a bank for a loan is called the ______.

Understanding the Main Ideas

Write answers to the following questions to review the main ideas in this chapter.

1.A person goes into a store and buys a pair of shoes with money. Is money here principally functioning as a medium of exchange, a store of value, or a unit of account?

2.Explain how money emerged out of a barter economy.

3.Why is a checking account sometimes called a demand deposit?

4.What is currency?

5.Explain how a check clears. Illustrate this process using two banks in the Federal Reserve district in which you live.

284 Chapter 10 Money, Banking, and the Federal Reserve System

6.List the locations of the 12 Federal Reserve district banks.

7.State what each of the following equals:

a.total reserves

b.required reserves

c.excess reserves

8.Determine which of the following Fed actions will increase the money supply: (a) lowering the reserve requirement, (b) raising the reserve requirement, (c) conducting an open market purchase, (d) conducting an open market sale,

(e) lowering the discount rate relative to the federal funds rate, (f) raising the discount rate relative to the federal funds rate.

9.What do we mean when we say that the Fed can create money “out of thin air”?

10.Explain how an open market purchase increases the money supply.

11.What is the relationship between changes in the reserve requirement and changes in the money supply?

12.Suppose the Fed sets the discount rate much higher than the existing federal funds rate. With this action, what signal is the Fed sending to banks?

Doing the Math

Do the calculations necessary to solve the following problems.

1.A tiny economy has the following money in circulation: 25 dimes, 10 nickels, 100 one-dollar bills, 200 five-dollar bills, and 40 twenty-dollar bills. In addition, traveler’s checks equal $500, balances in checking accounts equal $1,900, and balances in savings accounts equal $2,200. What is the money supply? Explain your answer.

2.A bank has $100 million in its reserve account at the Fed and $10 million in vault cash. The reserve requirement is 10 percent. What do total reserves equal?

3.The Fed conducts an open market purchase and increases the reserves of bank A by $2 million. The reserve requirement is 20 percent. By how much does the money supply increase?

Working with Graphs and Tables

1.In Exhibit 10-8, fill in the blanks (a), (b), and (c).

E X H I B I T 10-8

Fed buys government securities

Fed raises reserve

requirement

Fed raises the discount rate (relative to federal funds rate)

Money supply |

(a) |

|

Money supply |

(b) |

|

Money supply |

(c) |

|

Solving Economic Problems

Use your thinking skills and the information you learned in this chapter to find solutions to the following problems.

1.Cause and Effect. In year 1, reserves equal $100 billion, and the money supply equals $1,000 billion. In year 2, reserves equal $120 billion, and the money supply equals $1,200 billion. Did the greater money supply in year 2 cause the higher dollar amount of reserves, or did the higher dollar amount of reserves cause the greater money supply? Explain.

2.Writing. Write a one-page paper about some-

thing you enjoy that would not exist in a barter economy. Explain why it would not exist.

Go to www.emcp.net/economics and choose Economics: New Ways of Thinking, Chapter 10, if you need more help in preparing for the chapter test.

Chapter 10 Money, Banking, and the Federal Reserve System 285

Why It Matters

If you go to the doctor for a checkup, she will take your vital signs—your temperature, your blood pressure, and your pulse rate. When it comes to the economy, economists do much the same. This chapter discusses many of the measurements that economists make to determine the health

of the economy.

First, economists want to measure the total output of the economy. They want to measure the total market value of all the goods and services produced annually in the United States.

Think of it in this way: each year, people in the United States produce goods and

This relatively small trans- |

services—cars, houses, com- |

|

action is but one of mil- |

puters, attorney services, and |

|

lions that economists |

so on. Economists want to |

|

account for each year to |

know the total dollar value of |

|

measure the economy’s |

all these goods and services. |

|

activity. |

||

Another vital sign that |

||

|

||

|

economists want to monitor |

|

|

is prices. Are prices in the economy rising? If so, how fast are they rising? Are they rising by 1 percent, 3 percent, or 5 percent? Are prices falling? If so, how fast are they falling?

As you read this chapter, think of the economy as a patient in a doctor’s office. Instead of the doctor checking out the economy, an economist will take the economy’s “pulse,” “height and weight,” and other vital signs. In later chapters you will learn more about the remedies economists prescribe for an unhealthy economy.

286

The following events occurred one day in June.

1:13 P.M. Jones, the plumber, is just finishing up the job at Kevin’s apartment. Kevin asks Jones how much he owes him. Jones says, “$210.” “Okay,” says Kevin as he takes out his check-

book. “Oh, and by the way,” Jones adds, “could you pay me in cash?”

• Why does Jones want to be paid in cash?

1:34 P.M. The economics professor is telling her class that China has one of the highest gross domestic products of any country in the world. A student remarks, “But I thought China was a poor country. How can a poor country have a

high gross domestic product?”

• How can a country have a high GDP and be poor too?

2:34 P.M. Beverlee Smith picks up the phone to call her parents, both of whom are retired. When her father answers the phone, Beverlee blurts out, “I got

the job. And I got the salary I asked for—$60,000.” Her father replies, “That’s a great salary—you’re rich. After all, your mother and I lived comfortably on my first salary of $8,000.”

• What mistake is Beverlee’s father making in comparing his first salary (years ago) with her salary today?

8:00 P.M. Jimmy and Ellie are in their seats in the dark movie theater as the trailers play. They’re waiting for the start of the movie. Ads for the movie have been running on television for weeks. Jimmy turns to Ellie and whispers, “I heard that this movie might be the biggest box office hit of all time—even bigger than Titanic.”

• What’s the best way to compare the gross receipts of two movies?

11:03 P.M. Sam is watching a report on the 11 o’clock news about the growth rate in per capita real GDP in the United States over the last year. Sam is bored to tears. He says under his breath, “Who really cares about such things? That stuff doesn’t affect anyone.”

• Is Sam right that the growth rate in per capita real GDP doesn’t affect anyone?

287

National Income

Accounting

Focus Questions

What is GDP?

Why are only final goods and services computed in GDP?

What is omitted from GDP?

What is the difference between GDP and GNP?

Key Terms

gross domestic product (GDP) double counting

gross domestic product (GDP)

The total market value of all final goods and services produced annually in a country.

What Is Gross Domestic

Product?

A family has an income. For example, the annual income of the Smith family might be $90,000. A country has an income too, but we don’t call it an income. Instead, we call it gross domestic product. Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total market value of all final goods and services produced annually in a country. (Note: Sometimes GDP is referred to as nominal GDP. This is sometimes done to distinguish it from real GDP, which we will discuss later. )

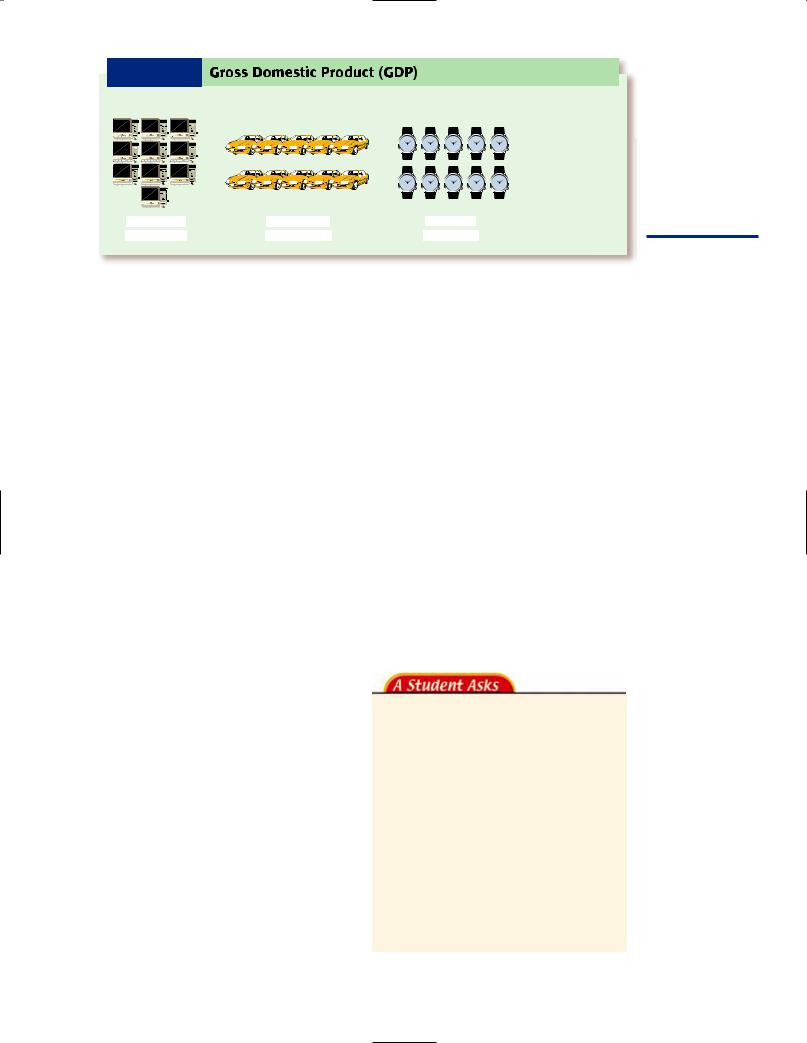

Suppose in a tiny economy only three goods are produced in these quantities: 10 computers, 10 cars, and 10 watches. We’ll say that the price of a computer is $2,000, the price of a car is $20,000, and the price of a watch is $100. If we wanted to find the GDP of this small economy—that is, if we wanted to find the total market value of the goods produced during the year—we would multiply the price of each good times the quantity of the good produced and then add the dollar amounts. (See Exhibit 11-1.)

1.Find the market value for each good produced. Multiply the price of each good times the quantity of the good produced. For example, if 10 computers are produced and the price of each is $2,000, then the market value of computers is $20,000.

2.Sum the market values.

Here are the calculations:

Market value of computers $2,000 10 computers $20,000

Market value of cars $20,000 10 cars $200,000

Market value of watches $100 10 watches $1,000

Gross domestic product $20,000 $200,000 $1,000 $221,000

This total, $221,000, is the gross domestic product, or GDP, of the tiny economy.

A tiny economy has two goods, A and B. It produces 100 units of A and 200 units of B this year. The price of A is

A tiny economy has two goods, A and B. It produces 100 units of A and 200 units of B this year. The price of A is

288 Chapter 11 Measuring Economic Performance

E X H I B I T 11-1 Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

10 computers |

10 cars |

10 watches |

GDP

$221,000

|

at $2,000 each |

|

|

at $20,000 each |

|

|

|

at $100 each |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

equals $20,000 |

equals $200,000 |

equals $1,000 |

||||||||

In our tiny example economy, the only goods produced are computers, cars, and watches. To calculate the GDP, we multiply the quantity of each good by its price, then sum the dollar amounts.

$4 and the price of B is $6. It follows that its GDP is $1,600. We got this dollar figure by finding the market value of A ($4 100 units $400), the market value of B ($6 200 units $1,200), and then adding the two values.

Why Count Only Final

Goods?

The definition of GDP specifies “final goods and services”; GDP is the total market value of all final goods and services produced annually in a country. Economists often distinguish between a final good and an intermediate good.

A final good is a good sold to its final user. When you buy a hamburger at a fastfood restaurant, for example, the hamburger is a final good. You are the final user; no one uses (eats) the hamburger other than you.

An intermediate good, in contrast, has not reached its final user. For example, consider the bun that the restaurant buys and on which the hamburger is placed. The bun is an intermediate good at this stage, because it is not yet in the hands of the final user (the person who buys the hamburger). It is in the hands of the people who run the restaurant, who use the bun, along with other goods (lettuce, mustard, hamburger meat), to produce a hamburger for sale.

When computing GDP, economists count only final goods and services. If they counted both final and intermediate goods and services, they would be double counting, or counting a good more than once.

Suppose that a book is a final good and that paper and ink are intermediate goods used to produce the book. In a way, we can say that the book is paper and ink (book paper ink). If we were to calculate the GDP by adding together the value of the book, the paper, and the ink (book paper ink), we would, in effect, be counting the paper and ink twice. Because the book is paper and ink, once we count the book, we have automatically counted the paper and the ink. It is not necessary to count them again.

A car is made up of many intermediate goods: tires, engine, steering wheel, radio, and so on. When computing GDP, we count only the market value of the car, not the market value of the car plus the market value of the tires, engine, and other intermediate goods.

A car is made up of many intermediate goods: tires, engine, steering wheel, radio, and so on. When computing GDP, we count only the market value of the car, not the market value of the car plus the market value of the tires, engine, and other intermediate goods.

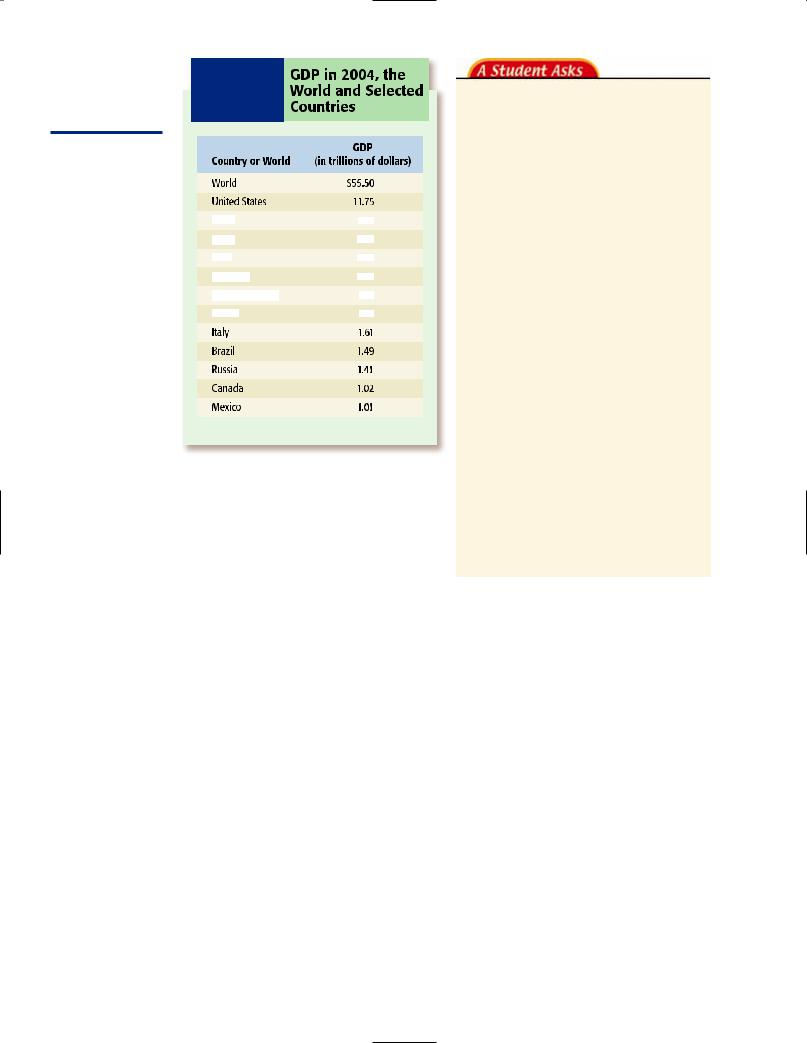

QUESTION: I assume that each country in the world computes its GDP. Why is GDP so important?

ANSWER: Countries are interested in computing their GDP for much the same reason that individuals are interested in knowing their income. Just as knowledge of your income from one year to the next lets you know “how you’re doing,” GDP does much the same for countries. Exhibit 11-2 on the next page shows the GDP for certain countries and for the world in 2004.

double counting

Counting a good more than once in computing GDP.

Section 1 National Income Accounting 289

Why do countries think it is important to keep track of their GDP?

E X H I B I T 11-2 GDP in 2004, the

|

World and Selected |

|

Countries |

|

GDP |

Country or World |

(in trillions of dollars) |

World |

$55.50 |

United States |

11.75 |

|

China |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7.26 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Japan |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

3.75 |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

India |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.32 |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Germany |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

2.36 |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

United Kingdom |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

1.78 |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

France |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.74 |

|||||

Italy |

1.61 |

Brazil |

1.49 |

Russia |

1.41 |

Canada |

1.02 |

Mexico |

1.01 |

Source: CIA World Factbook, 2005.

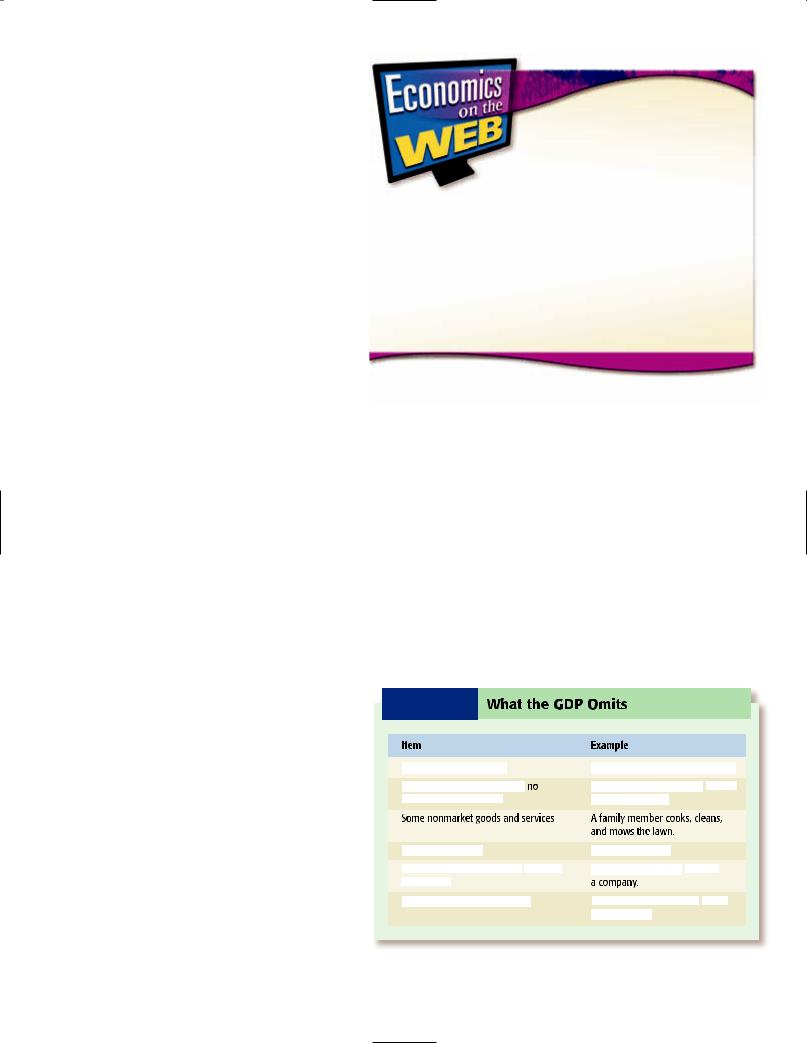

Does GDP Omit Anything?

Some exchanges that take place in an economy are omitted from the GDP measurement. The following are not included when calculating GDP.

QUESTION: Obviously, illegal transactions occur in the United States every day (such as dollars exchanged for illegal drugs), and other transactions that occur are “under the table” (such as a person being paid for his services in cash instead of with a check). Do economists know what percentage of all transactions these types of transactions account for?

ANSWER: Both illegal transactions and legal transactions that government authorities do not know about (such as cash transactions that do not include a receipt) make up what is called the underground economy. Some economists estimate that the underground economy in the United States is about 13 percent of the regular economy. In other words, for every $100 transaction in the regular economy, there is a $13 transaction in the underground economy. Keep in mind, though, that it is somewhat difficult to get a really good estimate of the underground economy because, by definition, it is largely invisible to economists. It is difficult to count what people are trying to prevent you from counting.

Illegal Goods and Services

For something to be included in the calculation of GDP, that something has to be capable of being counted. Illegal trades are not capable of being counted, for obvious reasons. For example, when someone makes an illegal purchase, no record is made of the transaction. The criminals involved in the transaction do everything in their power to prevent anyone from knowing about the transaction.

As you know, it is illegal in the United States to buy and sell drugs such as cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine. Suppose a person pays $400 to buy some of an illegal drug. This $400 is not counted in GDP. If, however, the person spends $40 to buy a book, this $40 is counted in GDP. It is not illegal to buy a book.

As you know, it is illegal in the United States to buy and sell drugs such as cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine. Suppose a person pays $400 to buy some of an illegal drug. This $400 is not counted in GDP. If, however, the person spends $40 to buy a book, this $40 is counted in GDP. It is not illegal to buy a book.

Transactions of Legal Goods and Services with No Record

Suppose a gardener goes to someone’s house and offers to mow the lawn and prune the shrubbery for $35 a week. The person agrees. The gardener then asks that he be paid in cash instead of by check and that no written record of the transaction be made. In other words, no sales receipt is provided. Again the person agrees. The payment for these gardening services does not find its way into GDP. A cash payment and no sales receipt mean that no evidence shows that a transaction was ever made.

Some Nonmarket Goods and Services

Some goods and services are traded, but not in an official market setting. Let’s say that Eileen Montoya cooks, cleans, and takes

290 Chapter 11 Measuring Economic Performance

care of all financial matters in the Montoya household. She is not paid for doing these activities; she does not receive a weekly salary from the family. Because she is not paid, the value of the work she performs is not counted in GDP.

Jayne has three young boys, ages 2 to 6. She cuts their hair every few weeks. The “market value” of these haircuts is not counted in GDP. However, if Jayne took her boys to a barber, and he cut their hair, what the barber charged for haircuts would be counted in GDP.

Jayne has three young boys, ages 2 to 6. She cuts their hair every few weeks. The “market value” of these haircuts is not counted in GDP. However, if Jayne took her boys to a barber, and he cut their hair, what the barber charged for haircuts would be counted in GDP.

Sales of Used Goods

Suppose you buy a used car tomorrow. Will this purchase be recorded in this year’s GDP statistics? No, a used car does not enter into the current year’s statistics because the car was counted when it was originally produced.

Mario just sold his 2002 Toyota to Jackson for $7,000. This $7,000 is not counted in GDP.

Mario just sold his 2002 Toyota to Jackson for $7,000. This $7,000 is not counted in GDP.

Stock Transactions and Other

Financial Transactions

Suppose Elizabeth buys 500 shares of stock from Keesha for a price of $100 a share. The total price is $50,000. The transaction is not included in GDP, because GDP is a record of goods and services produced annually in an economy. A person who buys stock is not buying a product but rather an ownership right in the firm that originally issued the stock. For example, when a person buys Coca-Cola stock, he is becoming an owner of the Coca-Cola Corporation.

Government Transfer Payments

In everyday life, one person makes a payment to another usually in exchange for a good or service. For example, Enrique may pay Harriet $40 to buy her old CD player.

When the government makes a payment to someone, it often does not get a good or service in exchange. When this happens, the payment is said to be a government transfer

Quite a bit of economic data can be found on the Web. Go to the Economic Statistics

Briefing Room at www.emcp.net/ employment and click on “Employment” if you want to find the current civilian labor force, number of persons unemployed, and unemployment rate. Click on “Prices” if you want to find the one-month change in the CPI. If you want to find the most current GDP figures, go to the Bureau of Economic Analysis at www.emcp.net/GDPfigures and click on “Frequently Requested NIPA Tables” and then “Gross Domestic Product.”

payment. For example, the Social Security check that 67-year-old Frank Simmons receives is a government transfer payment. Simmons, who is retired, is not currently supplying a good or service to the government in exchange for the Social Security check. Because GDP accounts for only current goods and services produced, and a transfer payment has nothing to do with current goods and services produced, transfer payments are properly omitted from GDP statistics. See Exhibit 11-3 for a review of items omitted from GDP.

E X H I B I T 11-3 What the GDP Omits

Item |

Example |

Illegal goods and services |

|

|

|

|

A person buys an illegal substance. |

||||

|

|

|

no |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legal goods and services with |

A gardener works for cash, |

and no |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

record of the transaction |

|

|

|

|

sales receipt exists. |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some nonmarket goods and services |

A family member cooks, cleans, |

and mows the lawn.

|

Sales of used goods |

|

|

|

|

|

You buy a used car. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Stock transactions and other |

financial |

You buy 100 shares of |

stock in |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

a company. |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

transactions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Government transfer payments |

|

|

Frank Simmons receives a |

Social |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Security check. |

||||||||

Section 1 National Income Accounting 291

E X H I B I T 11- 4 Gross National Product Does Not Equal Gross Domestic Product

|

|

|

GNP |

|

|

|

|

|

GDP |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total market value of final goods |

Total market value of final goods |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

and services produced by U.S. |

and services produced within |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

citizens (wherever they reside |

the borders of the United |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

the United States, France, |

States (by both citizens |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

Mexico, etc.) |

|

|

|

|

|

and noncitizens) |

|||||||||||

The producer’s citizenship matters in computing GNP. The producer’s place of residence matters in computing GDP.

The Difference Between

GDP and GNP

Economists, government officials, and members of the public talk about GDP when they want to discuss the overall performance of the economy. They might say, “GDP has been on the rise” or “GDP has been declining a bit.” It was not always GDP that these individuals talked about, though. They used to talk about GNP, the gross

national income, or GNI, instead of gross national product, GNP.)

What is the difference between GDP and GNP? GNP measures the total market value of final goods and services produced by U.S. citizens, no matter where in the world they reside. GDP, in contrast, is the total market value of final goods and services produced within the borders of the United States, no matter who produces them.

Suppose a U.S. citizen owns a business in Japan. The value of the output she is producing in Japan is counted in GNP because she is a U.S. citizen, but it is not counted in GDP because it was not produced within the borders of the United States. Now suppose a Canadian citizen is producing goods in the United States. The value of his output is not counted in GNP because he is not a U.S. citizen, but it is counted in GDP because it was produced within the borders of the United States. (See Exhibit 11-4.)

José is a Mexican citizen working in the United States. The dollar value of what he produces is counted in the U.S. GDP. Sabrina is a U.S. citizen living and work-

José is a Mexican citizen working in the United States. The dollar value of what he produces is counted in the U.S. GDP. Sabrina is a U.S. citizen living and work-

Defining Terms

1.Define:

a.gross domestic product (GDP)

b.double counting

Reviewing Facts and

Concepts

2.In a simple economy, three goods are produced during the year, in these quantities: 10 pens, 20 shirts, and 30 radios. The price of pens is $4 each, the price of shirts is $30 each, and the price of radios is $35 each. What is GDP for the economy?

3.Why are only final goods and services computed in GDP?

4.Which of the following are included in the calculation of this year’s GDP?

a.Twelve-year-old Bobby mowing his family’s lawn

b.Terry Yanemoto buying a used car

c.Barbara Wilson buying 100 shares of Chrysler Corporation stock

d.Stephen Sidwhali’s receipt of a Social Security check

e.An illegal sale at the corner of Elm and Jefferson

Critical Thinking

5.What is the difference (for purposes of measuring GDP) between buying a new computer and buying 100 shares of stock?

Applying Economic

Concepts

6.The government does not now include the housework that a person does for his or her family as part of GDP. Suppose the government were to include housework. How might it go about placing a dollar value on housework?

292 Chapter 11 Measuring Economic Performance

Measuring GDP

Focus Questions

What are the four sectors of the economy?

What are consumption, investment, government purchases, export spending, and import spending?

How is GDP measured?

What is per capita GDP?

Key Terms

consumption investment government purchases export spending import spending

How Is GDP Measured?

The GDP of the United States today is more than $12 trillion. How did economists come up with this figure? What exactly did they do to get this dollar amount?

First, economists break the economy into four sectors: the household sector, the business sector, the government sector, and the foreign sector. Next, they state a simple fact: the people in each of these sectors buy goods and services—that is, they make expenditures.

Economists give names to the expenditures made by each of the four sectors. The expenditures made by the household sector (or by consumers) are called consumption. The expenditures made by the business sector are called investment, and expenditures made by the government sector are called government purchases. (Government purchases include purchases made by all three levels of government—local, state, and federal.) Finally, the expenditures made by the residents of other countries on goods produced in the United States are called export spending. Exhibit 11-5 on page 294 gives

examples of goods purchased by households, businesses, government, and foreigners.

Consider all the goods and services produced in the U.S. economy in a year: houses, tractors, watches, restaurant meals, cars, computers, plasma television sets, DVDs, iPods, cell phones, and much, much more. Suppose someone from the household sector buys a DVD. This purchase falls into the category of consumption. When someone from the business sector buys a large machine to install in a factory, the purchase is considered an investment. If the U.S. government purchases a tank from a company that produces tanks, the purchase is considered a government purchase. If a person living in Sweden buys a U.S.-produced sweater, this purchase is considered spending on U.S. exports and therefore is registered as export spending.

All goods produced in the economy must be bought by someone in one of the four sectors of the economy. If economists simply sum the expenditures made by each sector— that is, if they sum consumption, investment, government purchases, and export spend- ing—they will be close to computing the GDP.

consumption

Expenditures made by the household sector.

investment

Expenditures made by the business sector.

government purchases

Expenditures made by the government sector. Government purchases do not include government transfer payments.

export spending

The amount spent by the residents of other countries for goods produced in the United States.

Section 2 Measuring GDP 293