- •Some Further Family Considerations

- •Enabling and Disabling Family Systems

- •Family Structure

- •Gender Roles and Gender Ideology

- •Cultural Diversity and the Family

- •Family Interactive Patterns

- •Family Narratives and Assumptions

- •Family Resiliency

- •The Perspective of Family Therapy

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •Social Factors and the Life Cycle

- •Developing a Life Cycle Perspective

- •The Family Life Cycle Framework

- •A Family Life Cycle Stage Model

- •Changing Families, Changing Relationships

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •Gender Issues in Families and Family Therapy

- •Multicultural and Culture-Specific Considerations

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •Some Characteristics of a Family System

- •Beyond the Family System: Ecosystemic Analysis

- •Families and Larger Systems

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •Historical Roots of Family Therapy

- •Studies of Schizophrenia and the Family

- •Marriage and Pre-Marriage Counseling

- •The Child Guidance Movement

- •Group Dynamics and Group Therapy

- •The Evolution of Family Therapy

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •Professional Issues

- •Maintaining Ethical Standards

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •7 PSYCHODYNAMIC MODELS

- •The Place of Theory

- •Some Historical Considerations

- •The Psychodynamic Outlook

- •Object Relations Theory

- •Object Relations Therapy

- •Kohut and Self Psychology

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •8 TRANSGENERATIONAL MODELS

- •Eight Interlocking Theoretical Concepts

- •Family Systems Therapy

- •Contextual Therapy

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •9 EXPERIENTIAL MODELS

- •A Shared Philosophical Commitment

- •The Experiential Model

- •Symbolic-Experiential Family Therapy (Whitaker)

- •Gestalt Family Therapy (Kempler)

- •The Human Validation Process Model (Satir)

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •10 THE STRUCTURAL MODEL

- •The Structural Outlook

- •Structural Family Theory

- •Structural Family Therapy

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •11 STRATEGIC MODELS

- •The Communications Outlook

- •The Strategic Outlook

- •MRI Interactional Family Therapy

- •MRI Brief Family Therapy

- •Strategic Family Therapy (Haley and Madanes)

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •12 THE MILAN SYSTEMIC MODEL

- •Milan Systemic Family Therapy

- •Questioning Family Belief Systems

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •Behavioral Therapy and Family Systems

- •A Growing Eclecticism: The Cognitive Connection

- •The Key Role of Assessment

- •Behaviorally Influenced Forms of Family Therapy

- •Functional Family Therapy

- •Conjoint Sex Therapy

- •A Constructivist Link

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •The Impact of the Postmodern Revolution

- •A Postmodern Therapeutic Outlook

- •The Post-Milan Link to the Postmodern View

- •Reality Is Invented, Not Discovered

- •Social Constructionist Therapies

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •Poststructuralism and Deconstructionism

- •Self-Narratives and Cultural Narratives

- •A Therapeutic Philosophy

- •Therapeutic Conversations

- •Therapeutic Ceremonies, Letters, and Leagues

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •Families and Mental Disorders

- •Medical Family Therapy

- •Short-Term Educational Programs

- •Recommended Readings

- •Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methodologies

- •Couple and Family Assessment Research

- •Family Therapy Process and Outcome Research

- •Evidence-Based Family Therapy: Some Closing Comments

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

- •Family Theories: A Comparative Overview

- •Family Therapies: A Comparative Overview

- •Summary

- •Recommended Readings

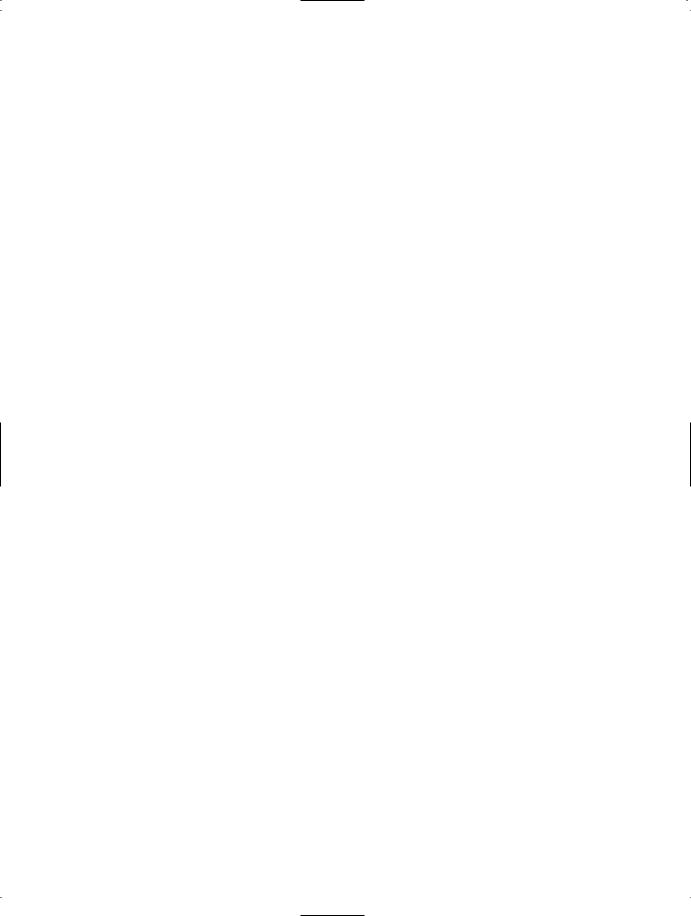

RESEARCH ON FAMILY ASSESSMENT AND THERAPEUTIC OUTCOMES 417

Stylistic Dimension |

Centripetal Mixed Centrifugal |

Severely |

|

|

|

|

|

Healthy |

|

||

|

Borderline |

|

Midrange |

|

Adequate |

|

Optimal |

|

|

disturbed |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Often |

|

Often |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

sociopathic |

|

borderline |

|

Often behavior |

|

|

|

|

|

offspring |

|

offspring |

|

disorders |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mixed |

|

Adequate |

|

Optimal |

|

Often |

|

Often severely |

Often neurotic |

|

|

|

|

||

schizophrenic |

obsessive |

|

offspring |

|

|

|

|

|

|

offspring |

|

offspring |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

9 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

Poor boundaries, |

Shift from |

|

Relatively clear |

Relatively clear |

Capable of |

|

|||

confused |

|

chaotic to |

|

communication; |

boundaries, |

|

negotiation, |

|

|

communication, |

|

tyrannical control |

constant effort |

|

negotiating but |

|

individual |

|

|

lack of shared |

|

efforts, |

|

at control: |

|

with pain, |

|

choice and |

|

attentional focus, |

boundaries |

|

“loving means |

|

ambivalence |

|

ambivalence |

|

|

stereotyped |

|

fluctuate |

|

controlling’’; |

|

reluctantly |

|

respected, |

|

family process, |

|

from poor to |

|

distancing, |

|

recognized, |

|

warmth, |

|

despair, cynicism, |

rigid, distancing, |

anger, anxiety |

|

some periods of |

intimacy, humor |

||||

denial of |

|

depression, |

|

or depression; |

|

warmth and |

|

|

|

ambivalence |

|

outbursts |

|

ambivalence |

|

sharing |

|

|

|

|

|

of rage |

|

handled by |

|

interspersed with |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

repression |

|

control struggles |

|

|

|

FIGURE 17.4 The Beavers Systems Model, in the form of a sideways A, with one leg representing centripetal families and the other leg representing centrifugal families

Source: Beavers & Voeller, 1983, p. 90

FAMILY THERAPY PROCESS AND OUTCOME RESEARCH

What constitutes therapeutic change? What are the conditions or in-therapy processes that facilitate or impede such changes? How are those changes best measured? How effective is family therapy in general, and are some intervention procedures or therapeutic models more efficacious than others for dealing with specific clinical problems or clients from a specific community or culture? Do certain specific therapist characteristics and family characteristics influence outcomes? Is family therapy the most cost-effective way to proceed in a specific case, say in comparison with alternate interventions such as individual therapy or drug therapy, or perhaps a combined set of therapeutic undertakings? How do race, ethnicity, gender, age, and sexual orientation factor into potential results? These are some of the questions that

418 CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

researchers in family therapy continue to grapple with in an effort to understand and improve the complex psychotherapeutic process.

For the last 40 years, psychotherapy research has concerned itself with investigating the therapeutic process (the mechanisms of client change) to develop more effective methods of psychotherapy. While the earlier years were devoted largely to outcome research studies in order to confirm the overall legitimacy of the therapeutic endeavor,“by about 1980 a consensus of sorts was reached that psychotherapy, as a generic treatment process, was demonstrably more effective than no treatment” (VandenBos, 1986, p. 111). A recent review of the research literature has found that 75 percent of those clients who enter psychotherapy show some benefit, with little difference between treatments (Lambert & Ogles, 2004). As for couple and family therapy, there now exists considerable research-informed evidence that this modality is effective for virtually every type of disorder and for a variety of relational problems in children, adolescents, and adults (Pinsof & Wynne, 2000; Friedlander & Tuason, 2000).

Now able to move beyond answering the simple outcome question “Does it work?”, researchers have turned their attention to comparative outcome studies in which the relative advantages and disadvantages of alternate treatment strategies for clients with different sets of problems are being probed. The research lens has now broadened to examine the application of couple and family therapy to specific clinical problems in specific settings (Sexton, Robbins, Hollimon, Mease, & Mayorga, 2003).

At the same time, explorations of process variables are taking place (Alexander, Newell, Robbins, & Turner, 1995), examining the nature of change mechanisms, so that differential outcomes from various therapeutic techniques can be tentatively linked to

Courtesy of Herbert and Irene Goldenberg

This researcher is in the process of viewing a series of videotapes of therapy sessions with the same family, rating certain interactive patterns along previously determined empirical categories in an effort to measure changes as a result of family therapy.

RESEARCH ON FAMILY ASSESSMENT AND THERAPEUTIC OUTCOMES 419

the presence or absence of specific therapeutic processes. Such investigations of what really goes on inside the therapy room have the potential for identifying specific strategies or interventions that can lead to more effective treatment (Hogue, Liddle, Singer, & Leckrone, 2005).

Process Research

How do couples or families change as a result of going through a successful therapeutic experience? What actually occurs, within and outside the family therapy sessions, that leads to a desired therapeutic outcome? Is there evidence for a set of constructs common to all effective therapies? Do specific therapies make use of these concepts in different ways that are effective? Despite a growing interest in ferreting out precisely what change processes lead to what results (Heatherington, Friedlander, & Greenberg, 2005; Diamond & Diamond, 2002; Alexander, Holtzworth-Munroe, & Jameson, 1994) and a search for why certain therapies are more effective than others for specific problems, it remains true that relatively little is yet known about how personal change, as well as interpersonal change within a family, occurs in this context (Friedlander, Wildman, Heatherington, & Skowron, 1994). That is, in contrast to the growing empirically based data on the efficacy or effectiveness of family therapy, there is still a comparative paucity of major research undertakings on change process mechanisms in couple and family therapy. However, this situation is beginning to improve as new measuring instruments are developed and qualitative, discovery-oriented methodologies employed, producing in many cases some clinically meaningful if less methodologically rigorous research. Successful process research could have the effect of identifying those therapist interventions or therapist-client interactions or changes in client behaviors that lead to increasingly effective treatment. Such information is particularly relevant to practitioners and as such may help bridge the gap between researcher and practitioner (Sprenkle, 2003).

Process research attempts to discover and operationally describe what actually takes place during the course of therapy. What are the day-to-day features of the therapist-client relationship, the actual events or interactions that transpire during sessions that together make up the successful therapeutic experience? Can these be catalogued and measured? What specific clinical interventions lead to therapeutic breakthroughs? How can these best be broken down into smaller units that can be replicated by others, perhaps manualized when possible, and thus taught to trainees learning to become family therapists? Are there specific ways of intervening with families with specific types of problems that are more effective than other ways? What role does therapist gender play in how therapy proceeds? What about therapeutic style (proactive or reactive, interpretive or collaborative, and so on)? What factors determine who remains in treatment and who drops out early on? How do cultural variables influence the therapeutic process?

Answers to such therapeutic process-related questions need to be found in order to demonstrate the efficacy of a particular treatment approach—especially critical at this time to the survival of family therapy in the healthcare marketplace (Alexander, Newell, Robbins, & Turner, 1995). From a practical economic viewpoint, family therapy research must demonstrate to insurance companies, managed care organizations, government agencies, and mental health policymakers that its product is an effective treatment that should be included in any package of mental health services (Pinsof & Hambright, 2002).

420 CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

B O X 1 7 . 3 T H E R A P E U T I C E N C O U N T E R

WHAT WITHIN-SESSION MECHANISMS STIMULATE CHANGE?

Alliance between the family and a caring, competent therapist attuned to the family’s presenting problem, especially if established early in therapy; this alliance builds confidence, hope, and a feeling of safety

Cognitive changes in clients: greater awareness and understanding and a shared sense of purpose

Behavioral changes in clients: sustaining engagement with one another

An emotional experience leading to having one’s feelings validated by other family members Maintenance of the therapeutic focus on strength-

ening family relations rather than blaming the identified patient

Promotion of constructive dialogue and the therapist’s effort to block the exchange of negative affect and interactional impasses

Greater self-disclosure, which makes participants feel vulnerable but listened to and protected

Sustained engagement, which leads to the feeling all members are working together for the overall family good

Sources: Sexton, Robbins, Hollimon, Mease, & Mayorga, 2003: Heatherington, Friedlander, & Greenberg, 2005; Christensen, Russell, Miller & Peterson, 1998; Helmeke & Sprenkle, 2000

Greenberg and Pinsof (1986) offer the following definition of process research:

Process research is the study of the interaction between the patient and therapist systems. The goal of process research is to identify the change processes in the interaction between these systems. Process research covers all the behaviors and experiences of these systems, within and outside the treatment sessions, which pertain to the process of change. (p. 18)

Note that in this definition the terms are used broadly. The patient (or client) system, for example, consists of more than the identified patient; other nuclear and extended family members are included, as well as members of other social systems that interact with the client and the family. Similarly, the therapist system might include other therapeutic team members in addition to the therapist who meets with the family.

Data from measuring the therapist-family interaction are also relevant here. Note too that process research does not simply concern itself with what transpires within the session, but also with out-of-session events occurring during the course of family therapy. Finally, the experiences, thoughts, and feelings of the participants are given as much credence as their observable actions. Thus, certain of the self-report methods we described earlier in this chapter may provide valuable input in the process analysis.

Process research attempts to reveal how therapy works, and what factors (in therapist behaviors, patient behaviors, and their interactive behaviors) are associated with improvement or deterioration. For example, a researcher might investigate a specific process variable concerning family interaction—who speaks first, who talks to whom, who interrupts whom, and so forth. Or perhaps, attending to therapist-family interaction, the researcher might ask if joining an anorectic family in an active and directive way results in a stronger therapeutic alliance than joining the family in a different way, such as being more passive or more reflective. Or perhaps the process researcher wants to find out what special ways of treating families with alcoholic members elicit willing

RESEARCH ON FAMILY ASSESSMENT AND THERAPEUTIC OUTCOMES 421

family participation as opposed to those that lead to resistance or dropouts from treatment. Are there certain intervention techniques that work best at an early treatment stage and others that are more effective during either the middle stage or terminating stage of family therapy?

By attempting to link process issues with outcome results, the family therapist would be proceeding using an empirically validated map, which unfortunately is not yet available for most models of family therapy (Pinsof & Hambright, 2002). There do exist some exceptions—what Heatherington, Friedlander, and Greenberg (2005) refer to as well-articulated theories about systemic change processes. Emotionally focused couple therapy (see Chapter 9) is based on considerable research on the role of emotion in therapy, integrates such research with attachment theory, and offers a step-by- step manualized therapeutic plan to help clients access and process their emotional experiences. Functional family therapy (Chapter 11) represents another successful effort to apply behavioral and systems theories to treat at-risk adolescents. Techniques for building therapeutic alliances and reframing the meaning of problematic behavior have been integrated into successful process studies (Robbins, Alexander, Newell, & Turner, 1996).

Empirically supported process studies thus far have been carried out primarily by the behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches. These brief, manualized treatment methods, with specific goals, are not necessarily the most effective, but are easier to test using traditional research methodology than other treatment methods. Least well defined, for research purposes, are the social constructionist therapies. By and large they have not yet developed testable propositions (e.g., how does the miracle question in solution-focused therapy affect client outcomes beyond a shift in “language games”?) (Heatherington, Friedlander, & Greenberg, 2005). Similarly, while narrative therapists purport to“re-author”people’s lives, how precisely can that be measured, and how do we know when re-authoring has been successful? For most models discussed in this text, greater evidence for the specifications of change mechanisms is still called for to meet the criteria of empirical researchers into how best to tap into the therapeutic change process.

Outcome Research

Ultimately, all forms of psychotherapy must provide some answer to this key question: Is this procedure more efficient, more cost-effective, less dangerous, with more long-lasting results than other therapeutic procedures (or no treatment at all)? Outcome research in family therapy must address the same problems that hinder such research in individual psychotherapy, in addition to the further complications of gauging and measuring the various interactions and changes taking place within a family group and between various family members.

To be meaningful, such research must do more than investigate general therapeutic efficacy; it must also determine the conditions under which family therapy is effective—the types of families, their ethnic or social class backgrounds, the category of problems or situations, the level of family functioning, the therapeutic techniques, the treatment objectives or goals, and so on. Effective research needs to provide evidence for what models work best for what specific problems, and what specific problems are especially responsive to family-level interventions.

Overall, according to the meta-analysis of the findings of 163 published and unpublished outcome studies on the efficacy and effectiveness of marital and family

422 CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

B O X 1 7 . 4 R E S E A R C H R E P O R T

EFFICACY STUDIES VERSUS EFFECTIVENESS STUDIES

Published outcome research studies today appear in one of two forms: efficacy studies, conducted under controlled (“laboratory”) conditions, and effectiveness studies, as in the everyday practice (“in the field”) of providing family therapy services (Pinsof & Wynne, 1995). Efficacy studies seek to discover whether a particular treatment works under ideal “research therapy” situations, while effectiveness studies seek to determine whether the treatment works under normal real-life (“clinic therapy”) circumstances. Historically, most outcome studies have focused on efficacy, in effect asking whether a specific treatment approach works under ideal, controlled research conditions. Unfortunately, as Pinsof and Wynne (2000) have more recently pointed out, such laboratory studies, while more readily funded and publishable than are effectiveness studies, nevertheless often bear so slight a likeness to what practitioners do in their everyday practice that they are likely to have little, if any, impact on the practices of most marriage and family therapists.

Outcome research projects carrying out efficacy studies are able to approximate ideal experimental requirements: patients are randomly assigned to treatment or no treatment groups, treatment manuals define the main procedures to be followed, therapists receive training and supervision to ensure standardization of interventions, multiple outcome criteria are designed, and independent evaluators (rather than the therapist or clients) measure outcomes. Such a “dream” setup, under such controlled conditions, often lends itself to a clarification of what components of the therapy specifically affect certain outcomes, and as such may be illuminating. However, the conclusions from such studies, usually carried out in university clinics or hospital settings, are often difficult to translate into specific recommendations for therapy under more real-world, consultation room conditions. Recent efforts to develop empirically supported family therapy represent a concerted effort to bring the mounting research to bear on problems that practicing clinicians deal with in their work.

therapy, Shadish, Ragsdale, Glaser, and Montgomery (1995) conclude that, based mainly on efficacy studies, these modalities work; marital/family therapy (MFT) clients did significantly better than untreated control group clients. As they put it in more concrete terms:

It means that if you randomly chose a client who received MFT, the odds are roughly two out of three that the treatment client will be doing better than a randomly chosen control client at posttest. . . . An effect this big is also considerably larger than one typically finds in medical, surgical, and pharmaceutical outcome trials. (p. 347)

While different marital and family therapy approaches all were found to be superior to no treatment, these reviewers found no single model’s efforts stood out over others. (It should be noted, however, that one approach or another may “fit” certain families better than do others, or work best for certain kinds of presenting problems. In addition, certain therapists may be especially skilled or especially experienced in helping families with certain specific sets of problems.) In some cases, a combination of therapeutic efforts (psychoeducational, medication, individual therapy, group therapy) may be the treatment of choice (Pinsof, Wynne, & Hambright, 1996).

A variety of outcome studies, some more carefully designed than others, have lent general support to the effectiveness of specific therapies. Minuchin, Rosman, and

RESEARCH ON FAMILY ASSESSMENT AND THERAPEUTIC OUTCOMES 423

Baker’s (1978) structural family therapy resulted in a 90 percent improvement rate for 43 anorectic children; that improvement still held in a follow-up several years later. Murdock and Gore (2004) confirmed Bowenian theory that self-differentiation influences how family members perceive stress in their lives. In an early, non-rigorous evaluation of strategic therapy, Watzlawick, Weakland, and Fisch (1974) checked on families three months after concluding treatment and found that 40 percent reported full symptom relief, 32 percent reported a considerable amount of relief, and 28 percent reported no change. Carr’s (1991) review of 10 studies of Milan therapy found a reported rate of 66 percent to 75 percent in symptom reduction in clients. While these results hint at effectiveness of the models espoused, they lack sufficient rigor in methodological design to offer any definitive conclusions regarding general empirically supported effectiveness for any one model.

In recent years, however, research methodology has improved, new statistical methods have become available, and funding has allowed for major research undertakings, particularly studies regarding which models work for specific populations. Evidence supporting family-level interventions have been especially strong for adolescent conduct or behavioral problems, and these approaches are gaining acceptance by practitioners as well as county and state healthcare administrators. Especially noteworthy here are functional family therapy, engaging high-risk, acting-out youth and their families by helping change those intra-family cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes that support the problem (Alexander & Sexton, 2002); multisystemic therapy, a manualized, integrated family approach treating chronic juvenile behavioral and emotional problems by addressing the multiple determinants of antisocial behavior and intervening at the family, peer, school, and community levels (Henggeler, Mihalic, Rone, Thomas, & Timmons-Mitchell (1998); and parent management training, a brief skills training program based on social learning principles, designed to assist parents at home in changing the behavior of severely oppositional or antisocial children and adolescents (Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1997).

Family-based treatments for substance-abusing adults and adolescents have received empirical support (Stanton & Shadish, 1997). One long-term approach carried out by Jose Szapocznik and associates (Szapocznik et al., 2002), called brief strategic family therapy, utilizes strategic and structural principles to treat behavior problems and substance abuse in Hispanic youth, within a family setting at home. In a similar vein, Malgady and Costantino (2003) report the empirically supported use of narrative therapy in which a group therapy format, sometimes including parents, was used to relate cultural narratives relevant to Puerto Rican and Mexican children and adolescents with conduct disorders, phobias, and anxiety.

Family-level interventions with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, augmented by pharmaceutical treatment, have largely been of a psychoeducational nature (see Chapter 16), teaching families about the disorder and how best to help avoid relapse. Families are taught that they have a significant influence on their relative’s recovery. A significant number of well-designed, empirically supported studies have demonstrated a markedly decreased relapse and rehospitalization rate for schizophrenic patients whose families received psychoeducation compared with those who received standard individual service (McFarlane, Dixon, Lukens, & Luckstead, 2003). Miklowitz et al. (2000) have reported similar findings for bipolar disorders in the clinical trials he and his group conducted.