- •Preface

- •Contents

- •1 Introduction

- •Layered Materials and Their Electronic Structure

- •General Phase Diagram of Cuprates and Main Questions

- •Superconducting State: Symmetry of the Order Parameter

- •Triplet Pairing in Strontium Ruthenate (Sr2RuO4): Main Facts and Main Questions

- •From the Crystal Structure to Electronic Properties

- •Spin Fluctuation Mechanism for Superconductivity

- •References

- •Generalized Eliashberg Equations for Cuprates and Strontium Ruthenate

- •Theory for Underdoped Cuprates

- •Extensions for the Inclusion of a d-Wave Pseudogap

- •Derivation of Important Formulae and Quantities

- •Elementary Excitations

- •Raman Scattering Intensity Including Vertex Corrections

- •Optical Conductivity

- •Comparison with Similar Approaches for Cuprates

- •The Spin Bag Mechanism

- •Other Scenarios for Cuprates: Doping a Mott Insulator

- •Local vs. Nonlocal Correlations

- •The Large-U Limit

- •Projected Trial Wave Functions and the RVB Picture

- •Current Research and Discussion

- •References

- •The Spectral Density Observed by ARPES: Explanation of the Kink Feature

- •Raman Response and its Relation to the Anisotropy and Temperature Dependence of the Scattering Rate

- •A Reinvestigation of Inelastic Neutron Scattering

- •Collective Modes in Electronic Raman Scattering?

- •Elementary Excitations and the Phase Diagram

- •Optical Conductivity and Electronic Raman Response

- •Brief Summary of the Consequences of the Pseudogap

- •References

- •4 Results for Sr2RuO4

- •Elementary Spin Excitations in the Normal State of Sr2RuO4

- •The Role of Hybridization

- •Comparison with Experiment

- •Symmetry Analysis of the Superconducting Order Parameter

- •Triplet Pairing Arising from Spin Excitations

- •Summary, Comparison with Cuprates, and Outlook

- •References

- •5 Summary, Conclusions, and Critical remarks

- •References

- •References

- •Index

192 4 Results for Sr2RuO4

k z

RuO2

RuO2

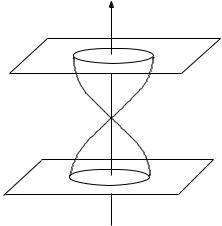

Fig. 4.11. Schematic representation of the kz dependence of the superconducting order parameter. Here, the amplitude of the order parameter along kz has been drawn in cylindrical coordinates between RuO2 planes. Owing to inclusion of spin– orbit coupling, one expects nodes between these planes.

ously, spin–orbit coupling results in mixing of the spin and orbital degrees of freedom. The new quasiparticles are labeled with pseudo–spin and pseudo– orbital quantum numbers. Furthermore, the spin–orbit coupling introduces a magnetic anisotropy along the z direction and, as a result, a superconducting state with a preferred direction of the orbital moment is realized. As has been shown in [30], the “chiral” state is indeed lower in energy in an RuO2 plane for a realistic set of parameters, suggesting that the dxy orbital is the orbital mostly involved in superconductivity.

4.3 Summary, Comparison with Cuprates, and Outlook

In summary, using a two-dimensional Hubbard Hamiltonian for the three electronic bands crossing the Fermi level in Sr2RuO4, we have employed a tight–binding description of the band structure and calculated the spin susceptibility χ(q, ω) and have found the results to be in quantitative agreement with nuclear magnetic resonance and inelastic neutron scattering experiments. The susceptibility has two peaks at Qi = (2π/3, 2π/3) due to the nesting properties of the Fermi surface and a peak at qi = (0.6π, 0) due to the tendency towards ferromagnetism.

First, we have considered hybridization between all three bands and shown that this is important because it transfers the nesting properties of the xz and yz orbitals to the γ band in Sr2RuO4. Taking into account all crosssusceptibilities, we can successfully explain the 17O Knight shift and INS data. Most importantly, by applying spin–fluctuation exchange theory, have

4.3 Summary, Comparison with Cuprates, and Outlook |

193 |

shown, on the basis of only the Fermi surface topology and the calculated spin susceptibility χ(q, ω), that triplet pairing is present in Sr2RuO4. We can exclude s and d wave symmetry for the superconducting order parameter. These calculations we done without spin–orbit coupling and we found that f –wave symmetry pairing is slightly favored over p–wave symmetry. To decide whether p– or f –wave symmetry pairing or nodes between the RuO2 planes are present in Sr2RuO4, one needs to perform more complete calculations, including coupling between RuO2 planes for example. If the interplane coupling also involves nesting, then corresponding nodes reflecting the incommensurability of the excitations are expected. In view of Fig. 4.9, we also remark that while Re∆f exhibits three line nodes that can be seen by phase–sensitive experiments, |∆f |2 shows nodes only along the diagonals, as recently found in measurements of ultrasound attenuation below Tc [34]. However, in view of the low eigenvalues for the p– and f –wave symmetries and the di erent approximations used, we cannot definitely conclude that f –wave symmetry is favored over p–wave.

Secondly, we have considered the inclusion of spin–orbit coupling and have found that this is important because it couples the orbital and spin degrees of freedom. Thus the orbital anisotropy (the nested α and β bands are quasi–one–dimensional and the γ band is almost a circle) is then reflected in the spin response of the system, which can be measured by the NMR spin–lattice relaxation rate 1/T1T vs. T , for example. In the normal state we find the important result that χzz > χ+− for small temperatures T , in good agreement with experiment. Simply speaking, the in–plane response is mainly ferromagnetic-like and the out–of–plane response is mainly antiferromagnetic–like and dominated by the wave vectors Qi. We also have investigated the symmetry of the order parameter when spin–orbit coupling is included. We find that triplet p–wave pairing within the RuO2 planes is favored owing to the importance of the small wave vectors qi and the fact that the γ band is not nested. The nesting properties are now present mainly in the quasi–one–dimensional β band and the corresponding antiferromagnetic spin excitations point along the z direction. Thus, in an electronic theory, if coupling between the RuO2 planes is taken into account, we expect nodes between the RuO2 planes and nodeless p–wave pairing within the RuO2 planes.

In comparison with high–Tc cuprate superconductors, we can say the following. In both hole–doped and electron-doped cuprates, a one–band tight– binding description is appropriate for explaining the electronic properties, whereas in Sr2RuO4 a three–band picture with hybridization between the bands and the inclusion of spin–orbit coupling is necessary. For Sr2RuO4 as well as for the cuprates, one finds that spin fluctuations are present and are mainly of antiferromagnetic character. However, owing to the tendency towards ferromagnetism and the presence of incommensurate spin fluctuations in Sr2RuO4, this material is close to a spin-triplet superconducting phase transition. Physically speaking, if the spins of the quasiparticles are already

194 4 Results for Sr2RuO4

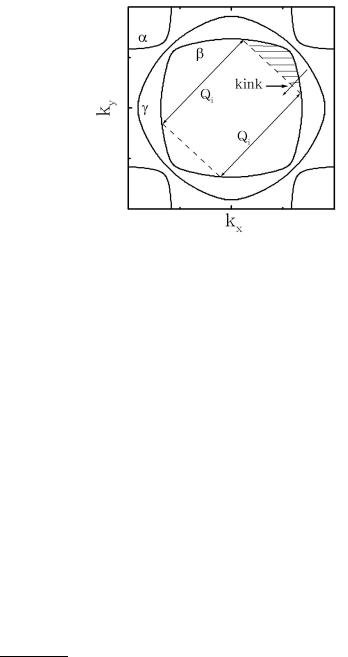

Fig. 4.12. Illustration of a possible kink structure in Sr2RuO4. The nesting properties of the β band lead to the formation of two–dimensional incommensurate spin fluctuations at Qi = (2π/3, 2π/3) and ωsf ≈ 6 meV. Therefore, the quasiparticles in the β band should be strongly renormalized owing to coupling to spin fluctuations.

(almost) aligned in the normal state (at least within the RuO2 planes), the superconducting state will be of triplet type because the energy gain in a simple Ginzburg–Landau description, ∆F = FS − FN (as discussed in Chap. 3), is large. In addition the antiferromagnetic spin excitations in the cuprates act within a CuO2 plane, yielding singlet d–wave pairing, whereas in Sr2RuO4 the antiferromagnetic spin excitations point along the z direction. The remaining ferromagnetic spin excitations within the RuO2 planes yield (also because of a high density of states) triplet p–wave pairing.

In order to compare the pairing mechanisms in more detail, we would like to point out that the main di erence between Fig. 3.10b for the electron– doped cuprate superconductor Nd2−xCexCuO4 (NCCO) and Fig. 4.9 is the sign change of the order parameter along the diagonal directions in the first Brillouin zone. This is consistent with the fact that the pairing potentials for singlet and triplet pairing (see (2.47) and (2.48)) also yield di erent signs owing to Pauli’s principle. Simply speaking, singlet pairing in cuprates consists of a repulsive interaction in k–space3, whereas the exchange of spin fluctuations yielding triplet pairing is attractive in momentum space and thus similar to phonons. Therefore, singlet Cooper pairing in cuprates naturally leads to d-wave symmetry of the superconducting order parameter ∆, because nodes and sign changes in ∆ are required to solve the corresponding

3 Of course, in real space on a lattice, after Fourier transformation, quasiparticles on nearest-neighbor sites interact with an attractive pairing potential. The terms “repulsive” and “attractive” that we use here refer to momentum space in the spirit of the BCS theory.

4.3 Summary, Comparison with Cuprates, and Outlook |

195 |

gap equation. On the other hand, an attractive pairing in k–space, which is present in Sr2RuO4, does not favor the existence of nodes in general. Thus, to a first approximation, one would expect a p–wave symmetry of ∆. However, if spin fluctuations are mainly antiferromagnetic and the nesting of the corresponding bands is strong, it is also possible to find f –wave pairing and thus nodes in Sr2RuO4. Finally, we have included spin–orbit coupling and find that these nodes should occur between the RuO2 planes. Phase-sensitive measurements (as in cuprates) should be performed in order to clarify this issue.

Finally, we want to emphasize that the important formation of the kink feature due to spin fluctuations is not expected to be restricted to cuprates. As discussed above, Sr2RuO4 reveals pronounced incommensurate antiferromagnetic spin fluctuations at a wave vector Qi = (2π/3, 2π/3) and frequency ωsf ≈ 6 meV that originate from the nesting properties of the quasi–one– dimensional α and β bands. Thus, on general grounds, one would expect a kink structure in the renormalized energy dispersion of the quasiparticles (see Fig. 4.12 for an illustration). Although the correlation e ects are weaker in Sr2RuO4 (U is smaller and it is a Fermi liquid), and Qi is an incommensurate wave vector, similar conditions to those in cuprates are present. Note that the kink feature should occur at smaller energies than in cuprates owing to the lower value of ωsf in the ruthenates. Recent ARPES data support this picture [35].

What are the next steps for a theory of strontium ruthenate? Interestingly, in Ca2−xSrxRuO4 various phase transitions occur, and a transition from triplet superconductivity in Sr2RuO4 to an antiferromagnetic Mott– Hubbard insulator in Ca2RuO4 has been found [36]. For example, for x < 0.2, Ca2−xSrxRuO4 is an insulator, and for the doping range 0.2 < x < 0.5 this material is a metal with short-range antiferromagnetic order. At x 0.5 there is a crossover which is accompanied by a sharp enhancement of the ferromagnetic fluctuations in the uniform spin susceptibility. Only for x → 2 the system does become superconducting with triplet Cooper pairing.

Recently, an attempt to explain the magnetic phase diagram of the material Sr2−xCaxRuO4 has been made on the basis of ab initio band structure calculations [37]. It has been shown that the rotations of the RuO6 octahedra around the c axis stabilize the ferromagnetic state, since they are su cient to reduce the pd–π hybridization between the xy orbitals and the oxygen 2p states. Consequently the xy band becomes narrower and the van Hove singularity shifts towards the Fermi level. At the same time, the xz and yz bands are only slightly a ected. On the other hand, the rotation around axes within the ab plane changes all three bands completely and increases the nesting of the xz and yz bands, and may stabilize the antiferromagnetic phase [37].

In such a picture, it is easy to understand why the ferromagnetic fluctuation are strongly enhanced around the so–called critical doping x 0.5. Using the LDA parameters for the tight–binding energy dispersion, we have calcu-

196 4 Results for Sr2RuO4

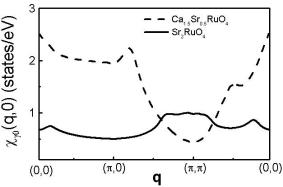

Fig. 4.13. The calculated real part of the Lindhard response function χγ0(q, 0) along the symmetry points in the BZ, for the γ band in Ca0.5Sr1.5RuO4 and Sr2RuO4. Owing to the closeness of the van Hove singularity, the response of the γ band is strongly enhanced and ferromagnetic (around q = 0). This is in fair agreement with experiment [38].

lated the Lindhard response function of the xy band for Ca0.5Sr1.5RuO4 and Sr2RuO4, as shown in Fig. 4.13. One can clearly see that the ferromagnetic response of the xy(γ) band is strongly enhanced at q = 0 owing the closeness of the van Hove singularity. Furthermore, since the α and β bands are almost unchanged, the ferromagnetic response becomes much stronger than the antiferromagnetic response, indicating the dominance of the ferromagnetic fluctuations around this critical point x 0.5. This is in good agreement with experiment [38]. However, this model cannot explain the Mott–Hubbard transition in Ca2RuO4 at finite temperatures, of course, since Ca2RuO4 remains an insulator even above TN . Therefore, strong electronic correlations have to be taken into account, as proposed recently by Ovchinnikov [39]. He suggested that while the xz and yz bands are split into lower and upper Hubbard bands, the xy band does not split although it is close to the Mott–Hubbard transition.

Finally, although our calculations we performed in the clean limit, one might ask what happens if impurities are added to Sr2RuO4. It is well known that unconventional superconductors show peculiar behavior if one adds magnetic or nonmagnetic impurities. In contrast to conventional (s–wave) superconductors, both nonmagnetic and magnetic impurities act as strong pair breakers and suppress the transition temperature Tc. This reflects the sensitivity to translational symmetry breaking and is characteristic of anisotropic Cooper pairing. The e ects induced by magnetic and nonmagnetic impurities in cuprates are not well understood. For example, when these materials are doped with nonmagnetic Zn, local magnetic moments within the CuO2 planes are induced around these impurities, which show a Kondo–like behavior [40].