IV.10.3 Other Reactions Involving

Palladacyclopropanes and

Palladacyclopropenes

ARMIN DE MEIJERE and OLIVER REISER

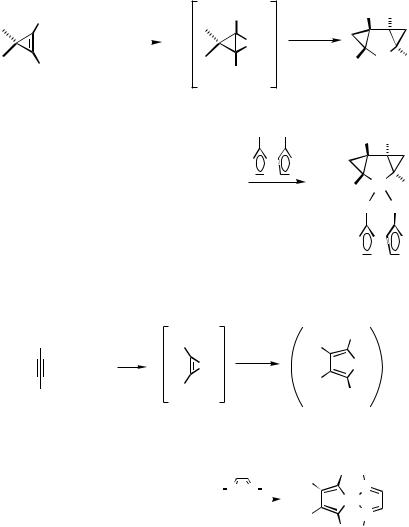

Although palladacyclopropanes and palladacyclopropenes can be postulated as intermediates when palladium in the oxidation state 0 or 2 interacts with an alkene or an alkyne, there is very little evidence that Pd-catalyzed reactions of alkenes and alkynes actually proceed this way.

In principle, a palladacyclopropane might be generated starting from palladium(0) or palladium(II) 1 and an alkene 2 (Scheme 1): after coordination to form a -complex 3, oxidative addition would yield a -complex 4, a pallada(II)- or pallada(IV)cyclopropane. Likewise, the analogous reaction with an alkyne 5 would lead to a palladacyclopropene 7.

0 or +2 |

|

|

|

0 or +2 |

|

+2 or +4 |

||||

Pd |

+ |

|

|

Pd |

|

Pd |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

4 |

||||||

0 or +2 |

|

|

|

0 or +2 |

|

+2 or +4 |

||||

Pd |

+ |

|

|

Pd |

|

Pd |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

5 |

6 |

|

7 |

||||||

|

|

Scheme 1 |

|

|

|

|

||||

Conclusive evidence for palladacyclopentanes[1] and palladacyclopentadienes[2],[3] as potentially stable intermediates has been put forward, and they have a close analogy to such metallacycles with other metals.[4],[5] They frequently are intermediates in metalcatalyzed or -mediated formal [2 2 2] cyclotrimerizations of alkynes and strained alkenes. It is plausible to assume that palladacyclopropanes or -cyclopropenes also play a role in such formal [2 2 2] processes catalyzed by palladium(0), for example, in the type of Pd-catalyzed cyclotrimerization of 3,3-dimethylcyclopropene reported by Binger et al.[6] (see also Sect. IV.2.4), for which a palladacyclopentane as intermediate was already isolated.[7] Moreover, dimethyl 3,3-dimethylcyclopropenedicarboxylate 8 has recently been shown to form the tricyclic palladacyclopentane derivative 10, the structure

Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis, Edited by Ei-ichi Negishi ISBN 0-471-31506-0 © 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

1647

1648 |

IV Pd-CATALYZED REACTIONS INVOLVING CARBOPALLADATIONS |

of which was proved by X-ray analysis of its 1,1 -bis(diphenylphosphinyl)ferrocene adduct 11 (Scheme 2).[1] It is most reasonable that 10 is formed via carbopalladation of 8 by the palladacyclopropane derivative 9.

Pd(dba)2 reacts rapidly with dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate (DMAD) to form the polymeric palladacyclopentadiene TCPC(13),[2] which could be fully characterized as diazadiene complexes 14 (Scheme 3).[3]

The palladacyclopropene 12 would most probably be an intermediate en route to 13, and, indeed, 1:1 complexes of palladium and DMAD have been obtained and characterized by 1H NMR and IR spectroscopy with stabilizing ligands such as triphenylphosphine[2] and N,N -di-tert-butyl-1,4-diaza-1,3-diene[3] present (Scheme 4). Unfortunately, however, it was

E

[Pd |

(dba) |

] |

CHCl |

2 |

3 |

|

3 |

E

8

E

+ Pd(dba)

2

E

E = COMe

2

E

8

Pd

E

9

PPh2 PPh2

Fe

Fe

Scheme 2

E E

DMAD

Pd

E

E

E E

E Pd E

10

E E

E |

Pd |

E |

|

|

|

Ph2P |

|

PPh2 |

Fe

Fe

11

E

Pd

E

n

12 |

|

13 |

|

|

|

|

|

E |

R |

|

R N |

|

E |

N |

|

N R |

|||

|

|

|

Pd |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

E |

N |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E |

R |

|

|

14 |

|

|

Scheme 3 |

|

|

|

|

IV.10.3 REACTIONS OF PALLADACYCLOPROPANES AND PALLADACYCLOPROPENES |

1649 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

E |

E |

PPh3 |

|

|

E |

|

PPh3 |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 PPh3 |

|

or |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

+ Pd(dba)2 |

|

Pd |

|

|

|

Pd |

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E |

PPh3 |

|

|

|

|

|

PPh3 |

|

|

E |

|

|

|

E |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

E = CO2Me |

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

16 |

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E |

t-Bu |

|

|

E |

|

t-Bu |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N |

|

|

|

N |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

or |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pd |

|

|

|

|

Pd |

|

|

|

|

|

|

t-Bu |

|

N N |

|

t-Bu |

E |

N |

|

|

|

|

|

N |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

t-Bu |

|

|

E |

|

t-Bu |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 |

|

|

|

|

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scheme 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

not possible to distinguish whether their structures are best described as -complexes 15 and 17 or as palladacyclopropenes 16 and 18, respectively, but the latter seem plausible by analogy to platinacyclopropenes being well established via similar pathways.[8]

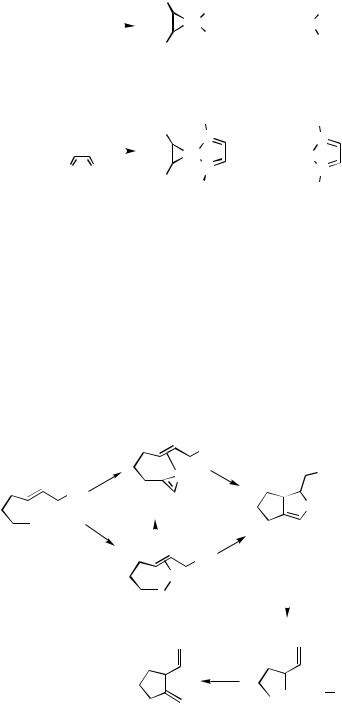

In enyne cycloisomerizations developed by Trost (see Sect. IV.2.5 and IV.3.1), palladacycles are also likely intermediates (Scheme 5).[9] In the palladium(II)-initiated cyclization of an enyne 19, the palladacyclopentene 21 has been postulated, requiring palladium to adopt the formal oxidation state 4. Catalytic cycles involving Pd(II) – Pd(IV) are not well precedented; however, by now several reactions have been reported in which Pd(IV) intermediates are most likely,[10] – [16] and one palladium(IV)

H

|

|

|

|

|

|

4+ |

|

H |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pd |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

H |

20 |

|

|

4+ |

|||

|

|

Pd2+ |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

Pd |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

H |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pd2+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

22 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

4+

Pd H

Pd H

23 |

24 |

Scheme 5

1650 IV Pd-CATALYZED REACTIONS INVOLVING CARBOPALLADATIONS

complex has been fully characterized by an X-ray crystal structure analysis.[17] Most probably, 21 would be formed from the -complex 22 via the palladacyclopropene 20 by intramolecular carbopalladation of the double bond.

REFERENCES

[1]A. S. K. Hashmi, F. Naumann, R. Probst, and J. W. Bats, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1997, 34, 104.

[2]K. Moseley and P. M. Maitlis, J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans., 1974, 169.

[3]H. tom Dieck, C. Munz, and C. Müller, J. Organomet. Chem., 1990, 384, 243.

[4]E. Negishi, Acc. Chem. Res., 1987, 20, 65–78.

[5]N. E. Schore, Chem. Rev., 1988, 88, 1081–1119.

[6]P. Binger, J. McMeeking, and U. Schuchardt, Chem. Ber., 1980, 113, 2372.

[7]P. Binger, H. M. Bück, R. Benn, and R. Mynott, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1982, 21, 62.

[8]G. B. Young, in Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry II: A Review of the Literature 1982–1994, Vol. 9, E. W. Abel, F. G. A. Stone, and G. Wilkinson, Eds., Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1995, 533–588.

[9]B. M. Trost, Acc. Chem. Res., 1990, 23, 34–42.

[10]A. J. Canty, Acc. Chem. Res., 1992, 25, 83–90.

[11]M. Catellani, G. P. Chiusoli, and C. Castagnoli, J. Organomet. Chem., 1991, 407, C30.

[12]O. Reiser, M. Weber, and A. de Meijere, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1989, 28, 1037.

[13]K. Albrecht, O. Reiser, M. Weber, B. Knieriem, and A. de Meijere, Tetrahedron, 1994, 50, 383.

[14]T. Ito, H. Tsuchiya, and A. Yamamoto, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn., 1977, 50, 1319.

[15]A. Moravskiy and J. K. Stille, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 102, 4182.

[16]M. K. Loar and J. K. Stille, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 4174.

[17]M. Catellani and M. C. Fagnola, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1995, 33, 2421.