Background Guide HSC autumn 2014

.pdf

IV ПЕРМСКАЯ МОДЕЛЬ ООН

HISTORICAL

SECURITY COUNCIL

Background Guide

«Kosovo War (1999)»

Оглавление |

|

Background and the causes of the war |

................................................................... 3 |

The beginning of the war ....................................................................................... |

8 |

The turning point and the later events................................................................. |

11 |

References ........................................................................................................... |

16 |

Glossary ............................................................................................................... |

17 |

2

Background and the causes of the war

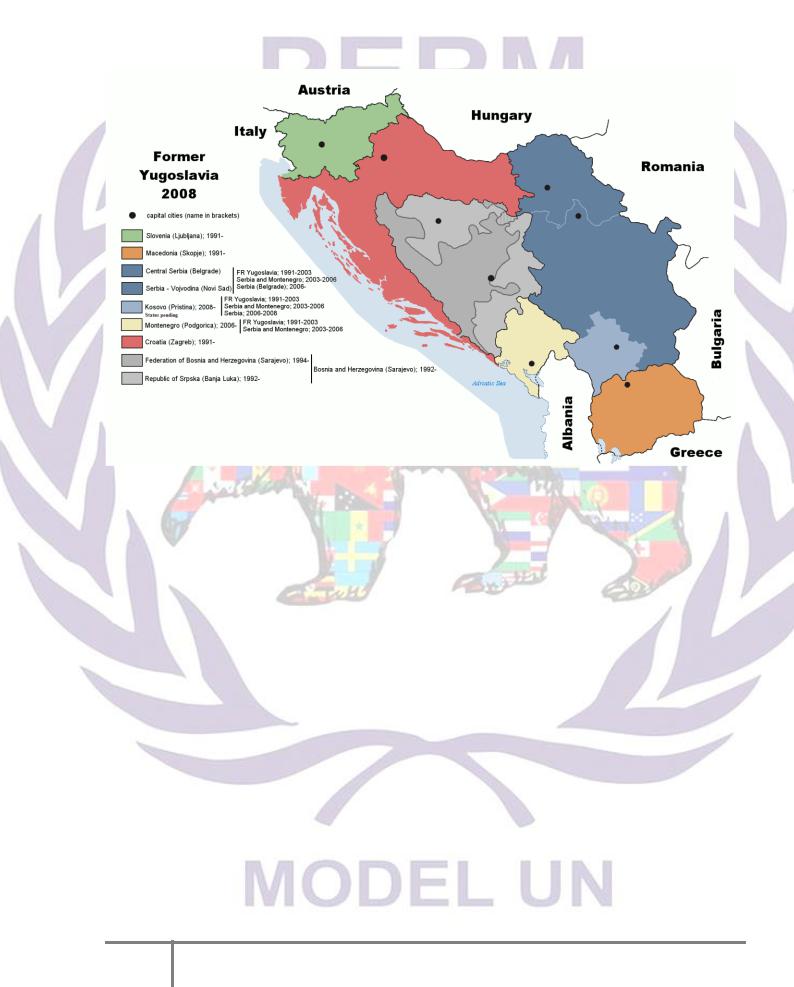

Today Kosovo is an area of less than 11,000 square kilometres in the south of the Republic of Serbia bordering, within the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the Republic of Montenegro to the north-west, and having international borders with the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia to the south and Albania to the west and south-west. Kosovo is inhabited by about two million people, ninety percent of which are ethnic Albanians. While ethnic tensions, calls for secession, and occasional riots were common features throughout Kosovo’s more recent history, it is only since the beginning of March, 1998, that organised and violent ethnic conflict has replaced an almost two decades-long peaceful struggle of ethnic Albanians to secure an independent state for themselves.

3

Kosovo has always been the backward region of Yugoslavia. Previous to the WWII there was not any industry on its territory, and even after industrialization it developed slower than the other regions. Workforce productivity, salaries and the living standards of the population were the lowest in Yugoslavia. In 1972 unemployment in Kosovo measured up to 20%. Kosovo was the poorest entity of Yugoslavia: the average per capita income was $795, compared with the national average of $2,635. Moreover, it was the least urbanized area with a lot of its people being peasants. Mass illiteracy contributed to the situation: in 1971 it reached 15.1% in Yugoslavia and 34.9% among Albanians only. As a result, superstitions and prejudice were dominating most rural areas. All of this paved the way for the dissatisfaction and nationalism among two major ethnicities of Kosovo.

Tensions between the Serbian and Albanian communities in Kosovo increased throughout the 20th century and occasionally erupted into major violence. The socialist government of

Josip Broz Tito (1945–1980) systematically repressed all manifestations of nationalism throughout Yugoslavia, seeking to ensure that no republic or nationality gained dominance over the others. In particular, the power of Serbia— the largest and most populous republic— was weakened by the establishment of autonomous governments in the province of Vojvodina in the north and Kosovo in

4

the south. In 1974 Kosovo's political status was improved further when a new Yugoslav constitution granted an expanded set of political rights. Along with Vojvodina, Kosovo was declared a province and gained many of the powers of a republic: a seat on the federal presidency and its own assembly, police force, and national bank.

Tito's death on 4 May 1980 set in motion a long period of political instability. Growing economic crisis and nationalist unrest made the situation even worse. The country was the first among the countries of Eastern bloc to implement the IMF doctrine that meant abandoning the policy of levelling the regions. This stopped the inflow of government

grants for Kosovo and triggered the national aggression. In March-May 1981 there were major student protests in Pristina (the capital of Kosovo), followed by urban riots and demands for Kosovo to be given republic status and rights of secession. At least ten people were killed, many more were injured and thousands were imprisoned and/or expelled from Kosovo's League of Communists. In 1981 it was reported that 4,000 Serbs moved from Kosovo to Central Serbia. Serbia reacted by a desire to reduce the power of the Albanians in the province, and a propaganda campaign that claimed that Serbs were being pushed out of the province primarily by the growing Albanian population, rather than the bad state of the economy. 33 nationalist formations were dismantled by the Yugoslav Police who sentenced 280 people (800 fined, 100 under investigation) and seized arms caches and propaganda material.

On April 24th, 1987 the Serbian Communist leader Slobodan Milosevic visited Kosovo apparently just to calm the Kosovo Serbs' anger against their perceived mistreatment. In the event he delivered an

5

inflammatory speech culminating in the words: «No one should dare to beat you!» Repeatedly broadcast on Serbian

television, this speech catapulted Milosevic to the forefront of the Serbian nationalist revival. He became president of Serbia in December 1987. In early 1989 the Serbian parliament passed constitutional amendments reasserting Serbian control over Kosovo.

In mid-1990, Serbs took control of

Kosovo's radio and television stations and major industrial enterprises, and closed or left the main Kosovar newspapers, theatres, libraries, museums and film units without any staff. School curricula were 'Serbianised' and Kosovar teachers were sacked. The University of Pristina was 'Serbianised' from September 1991. However, Kosovars soon organised an Albanian- language 'parallel' university and school system staffed by dismissed Kosovar teachers and a 'parallel health service' run by sacked Kosovar doctors and nurses. Despite that, everything was run on a shoestring and the incidence of poverty and disease increased.

After April 1990 most Kosovars embraced non-violent resistance under the leadership of the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), launched in December 1989 by Dr Ibrahim Rugova. The LDK held unofficial referenda and parallel elections to bolster its authority. However, in international negotiations on

6

former Yugoslavia non-violent Kosovo was simply ignored. Many Kosovars became bitterly disillusioned with Rugova's passivity after the Dayton Accords of November 1995, in which international sanctions against Serbia and Montenegro were lifted without a resolution of the Kosovo problem.

7

The beginning of the war

The first significant breaches of Kosovar non-violence occurred in 1995 and 1996, and the region finally erupted into armed conflict in 1998, partly as a consequence of the spring 1997 armed uprisings in Albania. The latter put into circulation over 700,000 weapons, many of which found their way to Kosovo. An organization calling itself the “Kosovo Liberation Army” (KLA) was formed. It attacked Serbian targets as a guerilla squad. A new Yugoslav government was also formed at this time, led by the Socialist Party of Serbia and the Serbian Radical Party. Ultra-nationalist

Radical Party chairman Vojislav Šešelj became a deputy prime minister.

8

This increased the dissatisfaction with the country's position among Western diplomats.

In early April Serbia arranged for a referendum on the issue of foreign interference in Kosovo. Serbian voters decisively rejected foreign interference in this crisis. Meanwhile, the KLA was pushing its way into the country. Therefore, on May 31 1998 the Yugoslav army and the Serb Ministry of the Interior police began an operation of crushing the KLA.

NATO’s response was ‘sending a signal’ to Milosevic (now the president of

Yugoslavia) – the Operation Determined Falcon, an air show over the Yugoslav borders.

During this time Milosevic reached an arrangement with Boris Yeltsin of Russia to stop offensive operations and prepare for talks with the Albanians, who previously refused to talk to the Serbian side. The agreement included Milosevic allowing international representatives to set up a mission in Kosovo to monitor the situation there. This was the Kosovo Diplomatic Observer Mission that began operations in early July.

In the meantime the KLA maintained its advance. In early midSeptember for the first time KLA activity was reported in northern Kosovo. The security forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) made a determined effort to clear the KLA out of the northern and central parts of the region.

On 23 September 1998 the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1199. This expressed 'grave concern' at reports reaching the Secretary General that over 230,000 people had been displaced from their homes by 'the excessive and indiscriminate use of force by Serbian security forces and the Yugoslav Army', demanding that all parties in Kosovo and the Federal

9

Republic of Yugoslavia cease hostilities and maintain a ceasefire. On 24 September the North Atlantic Council of NATO issued an "activation warning" taking NATO to an increased level of military preparedness for both a limited air option and a phased air campaign in Kosovo.

10