- •Contents

- •Authors

- •Foreword

- •Acknowledgments

- •Introduction

- •Selection of frameworks

- •Description and evaluation of individual frameworks

- •How to use this handbook

- •Overview of what follows

- •Chapter 1 The nature of thinking and thinking skills

- •Chapter 2 Lists, inventories, groups, taxonomies and frameworks

- •Chapter 3 Frameworks dealing with instructional design

- •Chapter 4 Frameworks dealing with productive thinking

- •Chapter 5 Frameworks dealing with cognitive structure and/or development

- •Chapter 6 Seven ‘all-embracing’ frameworks

- •Chapter 7 Moving from understanding to productive thinking: implications for practice

- •Perspectives on thinking

- •What is thinking?

- •Metacognition and self-regulation

- •Psychological perspectives

- •Sociological perspectives

- •Philosophical perspectives

- •Descriptive or normative?

- •Thinking skills and critical thinking

- •Thinking skills in education

- •Teaching thinking: programmes and approaches

- •Developments in instructional design

- •Bringing order to chaos

- •Objects of study

- •Frameworks

- •Lists

- •Groups

- •Taxonomies

- •Utility

- •Taxonomies and models

- •Maps, charts and diagrams

- •Examples

- •Bloom’s taxonomy

- •Guilford’s structure of intellect model

- •Gerlach and Sullivan’s taxonomy

- •Conclusion

- •Introduction

- •Time sequence of the instructional design frameworks

- •Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (cognitive domain) (1956)

- •Feuerstein’s theory of mediated learning through Instrumental Enrichment (1957)

- •Ausubel and Robinson’s six hierarchically-ordered categories (1969)

- •Williams’ model for developing thinking and feeling processes (1970)

- •Hannah and Michaelis’ comprehensive framework for instructional objectives (1977)

- •Stahl and Murphy’s domain of cognition taxonomic system (1981)

- •Biggs and Collis’ SOLO taxonomy (1982)

- •Quellmalz’s framework of thinking skills (1987)

- •Presseisen’s models of essential, complex and metacognitive thinking skills (1991)

- •Merrill’s instructional transaction theory (1992)

- •Anderson and Krathwohl’s revision of Bloom’s taxonomy (2001)

- •Gouge and Yates’ Arts Project taxonomies of arts reasoning and thinking skills (2002)

- •Description and evaluation of the instructional design frameworks

- •Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives: cognitive domain

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Description and intended use

- •Intellectual skills

- •Cognitive strategies

- •Motor skills

- •Attitudes

- •Evaluation

- •Ausubel and Robinson’s six hierarchically-ordered categories

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Williams’ model for developing thinking and feeling processes

- •Description and intended use

- •Cognitive behaviours

- •Affective behaviours

- •Evaluation

- •Hannah and Michaelis’ comprehensive framework for instructional objectives

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Stahl and Murphy’s domain of cognition taxonomic system

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Biggs and Collis’ SOLO taxonomy: Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Quellmalz’s framework of thinking skills

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Presseisen’s models of essential, complex and metacognitive thinking skills

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Merrill’s instructional transaction theory

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Anderson and Krathwohl’s revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives

- •Description and intended use

- •Changes in emphasis

- •Changes in terminology

- •Changes in structure

- •Evaluation

- •Gouge and Yates’ ARTS Project taxonomies of arts reasoning and thinking skills

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Some issues for further investigation

- •Introduction

- •Time sequence of the productive-thinking frameworks

- •Altshuller’s TRIZ Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (1956)

- •Allen, Feezel and Kauffie’s taxonomy of critical abilities related to the evaluation of verbal arguments (1967)

- •De Bono’s lateral and parallel thinking tools (1976 / 85)

- •Halpern’s reviews of critical thinking skills and dispositions (1984)

- •Baron’s model of the good thinker (1985)

- •Ennis’ taxonomy of critical thinking dispositions and abilities (1987)

- •Lipman’s modes of thinking and four main varieties of cognitive skill (1991/95)

- •Paul’s model of critical thinking (1993)

- •Jewell’s reasoning taxonomy for gifted children (1996)

- •Petty’s six-phase model of the creative process (1997)

- •Bailin’s intellectual resources for critical thinking (1999b)

- •Description and evaluation of productive-thinking frameworks

- •Description and intended use

- •Problem Definition: in which the would-be solver comes to an understanding of the problem

- •Selecting a Problem-Solving Tool

- •Generating solutions: using the tools

- •Solution evaluation

- •Evaluation

- •Allen, Feezel and Kauffie’s taxonomy of concepts and critical abilities related to the evaluation of verbal arguments

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •De Bono’s lateral and parallel thinking tools

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Halpern’s reviews of critical thinking skills and dispositions

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Baron’s model of the good thinker

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Ennis’ taxonomy of critical thinking dispositions and abilities

- •Description and intended use

- •Dispositions

- •Abilities

- •Clarify

- •Judge the basis for a decision

- •Infer

- •Make suppositions and integrate abilities

- •Use auxiliary critical thinking abilities

- •Evaluation

- •Lipman’s three modes of thinking and four main varieties of cognitive skill

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Paul’s model of critical thinking

- •Description and intended use

- •Elements of reasoning

- •Standards of critical thinking

- •Intellectual abilities

- •Intellectual traits

- •Evaluation

- •Jewell’s reasoning taxonomy for gifted children

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Petty’s six-phase model of the creative process

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Bailin’s intellectual resources for critical thinking

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Some issues for further investigation

- •Introduction

- •Time sequence of theoretical frameworks of cognitive structure and/or development

- •Piaget’s stage model of cognitive development (1950)

- •Guilford’s Structure of Intellect model (1956)

- •Perry’s developmental scheme (1968)

- •Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (1983)

- •Koplowitz’s theory of adult cognitive development (1984)

- •Belenky’s ‘Women’s Ways of Knowing’ developmental model (1986)

- •Carroll’s three-stratum theory of cognitive abilities (1993)

- •Demetriou’s integrated developmental model of the mind (1993)

- •King and Kitchener’s model of reflective judgment (1994)

- •Pintrich’s general framework for self-regulated learning (2000)

- •Theories of executive function

- •Description and evaluation of theoretical frameworks of cognitive structure and/or development

- •Piaget’s stage model of cognitive development

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Guilford’s Structure of Intellect model

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Perry’s developmental scheme

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Koplowitz’s theory of adult cognitive development

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Belenky’s ‘Women’s Ways of Knowing’ developmental model

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Carroll’s three-stratum theory of cognitive abilities

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Demetriou’s integrated developmental model of the mind

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •King and Kitchener’s model of reflective judgment

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Pintrich’s general framework for self-regulated learning

- •Description and intended use

- •Regulation of cognition

- •Cognitive planning and activation

- •Cognitive monitoring

- •Cognitive control and regulation

- •Cognitive reaction and reflection

- •Regulation of motivation and affect

- •Motivational planning and activation

- •Motivational monitoring

- •Motivational control and regulation

- •Motivational reaction and reflection

- •Regulation of behaviour

- •Behavioural forethought, planning and action

- •Behavioural monitoring and awareness

- •Behavioural control and regulation

- •Behavioural reaction and reflection

- •Regulation of context

- •Contextual forethought, planning and activation

- •Contextual monitoring

- •Contextual control and regulation

- •Contextual reaction and reflection

- •Evaluation

- •Theories of executive function

- •Description and potential relevance for education

- •Evaluation

- •Some issues for further investigation

- •6 Seven ‘all-embracing’ frameworks

- •Introduction

- •Time sequence of the all-embracing frameworks

- •Romiszowski’s analysis of knowledge and skills (1981)

- •Wallace and Adams’‘ Thinking Actively in a Social Context’ model (1990)

- •Jonassen and Tessmer’s taxonomy of learning outcomes (1996/7)

- •Hauenstein’s conceptual framework for educational objectives (1998)

- •Vermunt and Verloop’s categorisation of learning activities (1999)

- •Marzano’s new taxonomy of educational objectives (2001a; 2001b)

- •Sternberg’s model of abilities as developing expertise (2001)

- •Description and evaluation of seven all-embracing frameworks

- •Romiszowski’s analysis of knowledge and skills

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Jonassen and Tessmer’s taxonomy of learning outcomes

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Hauenstein’s conceptual framework for educational objectives

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Vermunt and Verloop’s categorisation of learning activities

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Marzano’s new taxonomy of educational objectives

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Sternberg’s model of abilities as developing expertise

- •Description and intended use

- •Evaluation

- •Some issues for further investigation

- •Overview

- •How are thinking skills classified?

- •Domain

- •Content

- •Process

- •Psychological aspects

- •Using thinking skills frameworks

- •Which frameworks are best suited to specific applications?

- •Developing appropriate pedagogies

- •Other applications of the frameworks and models

- •In which areas is there extensive or widely accepted knowledge?

- •In which areas is knowledge very limited or highly contested?

- •Constructing an integrated framework

- •Summary

- •References

- •Index

|

|

|

Cognitive structure and/or development |

195 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Practical illustrations |

|

Classification by: |

Values: |

for teachers: |

|

||

• |

developmental level |

• |

a mission as a |

• many have been |

|

• |

structural complexity |

|

major theorist |

produced by Piagetian |

|

• |

quality of |

• |

formal logical |

scholars, but a significant |

|

|

thought/action |

|

thinking |

proportion of these are now |

|

|

|

|

|

considered to be misleading |

|

|

|

|

|

or inappropriate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

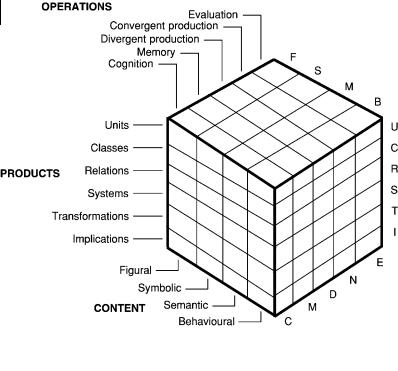

Guilford’s Structure of Intellect model

Description and intended use

Guilford’s Structure of Intellect (SI) model is a theory which aims to explain the nature of intelligence (Guilford, 1956; 1967; 1977; 1982; 1983; Guilford and Hoepfner, 1971). The purpose of the theory is to provide ‘a firm, comprehensive and systematic foundation’ and ‘empirically based’ concept of intelligence (Guilford, 1967, p. vii). It is based on experimental application of multivariate factor analysis of extensive studies of performance on psychometric tests. The resulting model (figure 5.1) is represented as a three-dimensional cuboid (5 4 6) with three main dimensions: operations, content and product complexity. The SI model is therefore a way of explaining thinking processes with these dimensions as key interrelated concepts. Subsequently, Guilford increased the possible number of subcategories to 150 (Guilford, 1982) and to 180 (Guilford, 1983).

The first dimension of ‘operations’ represents main intellectual functions, namely:

1.Cognition: recognising, understanding or comprehending information

2.Memory: stored information

3.Divergent production: generating a variety or quantity of alternative information

4.Convergent production: generating information through analysis and reason

5.Evaluation: comparing the information generated with established criteria.

196 Frameworks for Thinking

Fig. 5.1. Guilford’s Structure of Intellect model.

The second concept is ‘content’ or broad classes of information. These are identified as:

1.Figural: concrete information in images, using the senses of sight, touch, and hearing

2.Symbolic: with information represented by signs, letters, numbers or words which have no intrinsic value in and of themselves

3.Semantic: where meaning is contained in words such as verbal communication and thinking, or in pictures

4.Behavioural: nonverbal information about people’s attitudes, needs, moods, wishes and perceptions.

Products, or the form or characteristics of processed information make up the third concept:

1.Units: the separated items of information

2.Classes: items grouped by common characteristics

3.Relations: the connections between items based on the characteristics that can change

Cognitive structure and/or development |

197 |

|

|

4.Systems: interrelated parts and/or structured items of information

5.Transformations: changes in the existing information or its function

6.Implications: predictions, expected outcomes, or the particular consequences of the information.

Guilford is well-known for his work on creativity, where divergent production is the key concept (Guilford, 1950; 1986). In his view, creative people are sensitive to problems, fluent in their thinking and expression, and flexible (i.e. spontaneous and adaptable) in coming up with novel solutions.

The distinction between convergent and divergent production is just one of the features of the Structure of Intellect model which led Guilford (1980) to propose that it also provides a unifying theoretical basis for explaining individual differences in cognitive style as well as intelligence. He suggested that field independence may correspond with a broad set of ‘transformation’ abilities and that many cognitive style models are based on preferences for different types of content, process or product (e.g. visual content, the process of evaluation, products which are abstract).

Evaluation

SI theory is intended to be a general theory of human intelligence, capable of describing different kinds of skilled thinking as well as more basic cognitive processes. It is, for example, a high-level skill to evaluate (E) non-verbal information (B) about people’s attitudes to war and make reasonable predictions (I). Guilford’s cuboid model successfully conveys the idea that any or all of the operations, contents and products can work together in the course of thinking. His three dimensions are hard to challenge, since they refer to mental processes, forms of representation and structural properties of the elements and outcomes of thought. However, as Guilford himself notes, SI theory takes little account of the social nature of cognition (1967, p. 434).

Guilford researched and developed a wide variety of psychometric tests to measure the specific abilities predicted by the model. These tests provide operational definitions of these abilities. Factor

198 Frameworks for Thinking

analysis has been used to determine which tests appear to measure the same or different abilities and the literature contains both confirmatory evidence and criticism of the methods used by Guilford (see, for example, Horn and Knapp, 1973; Kail and Pellegrino, 1985; Bachelor, Michael and Kim, 1992; Sternberg and Grigorenko, 2000/2001).

There are clear theoretical links with Piaget (Guilford, 1967, p. 23) and with Bloom’s taxonomy (Guilford, 1967, p. 67). Guilford’s operations dimension lacks only Bloom’s ‘apply’ category. Sternberg and Grigorenko (2000/2001) state that Guilford was an early exponent of a broad definition of intelligence and, thus, he is owed a debt by later theorists such as Sternberg and Gardner who have argued for other conceptions than ‘g’.

A key facet of Guilford’s approach is his interest in creativity (Guilford, 1950). The ‘divergent production’ operation encompasses different combinations of process, product and content, and later theorists have built on these ideas (e.g. Torrance, 1966, McCrae, Arenberg and Costa, 1987 and Runco, 1992). However, Sternberg and Grigorenko (2000/2001) point out that more recent theories of creativity (including Sternberg’s own) differ from Guilford’s largely cognitive focus by also incorporating affective and motivational elements. They suggest that tests that include only cognitive variables will not strongly predict creative performance.

In relation to education, an important aspect of Guilford’s theory is that it considers intelligence as modifiable and that through accurate diagnosis and remediation, an individual’s performance in any of the areas of thinking can be improved. In addition, it can help educators to determine which skills are emphasised in any educational programme or system and which are neglected (Groth-Marnat, 1997). However, the very large number of different components of intelligence that can be derived renders practical examination and utilisation very complex.

Guilford’s SI model has been widely applied in employment recruitment through personnel selection and placement, as well as in education (e.g. the SOI programmes developed by Meeker, 1969). Sternberg and Bhana (1986) acknowledge that most children completing SOI programmes perform better on the post-test than on the pre-test, but

Cognitive structure and/or development |

199 |

|

|

suggest that this may be because of the similarity between SOI items and test items.

Concluding their review of his work, Sternberg and Grigorenko (2000/2001) acknowledge that ‘the interpersonal and intrapersonal factors of Gardner’s theory and the creative and practical facets of Sternberg’s theory both were adumbrated by Guilford’s behavioral dimension’ (Sternberg and Grigorenko, 2000/2001, p. 314). They also praise his scientific approach to theorising which permits rigorous testing and the possibility of disconfirmation.

Summary: Guilford

|

|

|

|

Relevance for teachers |

|

Purpose and structure |

Some key features |

and learning |

|||

|

|

|

|||

Main purpose(s): |

Terminology: |

Intended audience: |

|||

• |

to explain the |

• |

terminology is |

• |

academics |

|

nature of intelligence |

|

clear, but |

• |

educationists |

|

|

|

combinations of |

• |

personnel officers |

|

|

|

terms in the |

|

|

|

|

|

model are harder |

|

|

|

|

|

to understand |

|

|

Domains addressed: |

Presentation: |

Contexts: |

|||

• |

cognitive |

• |

through academic |

• |

education |

• |

affective (some |

|

publications in |

• |

vocational selection |

|

aspects through |

|

books and journals |

|

|

|

‘behavioural’ content) |

• |

the cuboid model |

|

|

|

|

|

brings logical |

|

|

|

|

|

structure to a |

|

|

|

|

|

highly complex field |

|

|

Broad categories covered: |

Theory base: |

Pedagogical stance: |

|||

• |

productive thinking |

• |

psychometrics |

• |

practice and feedback |

• |

building understanding |

|

and psychology |

|

are important, to |

• |

information-gathering |

• |

links are made |

|

overcome confusion |

• |

perception |

|

to the work of |

|

and help develop |

|

|

|

Piaget and Bloom |

|

transposable skills |

|

|

|

|

• |

diagnosing difficulties |

|

|

|

|

|

can lead to successful |

|

|

|

|

|

remediation |