- •Introduction to the Theory of Grammar

- •1. Grammar as part of language. Grammar as a linguistic discipline.

- •2. Parts of Grammar. Paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations of grammatical

- •1. Grammatical meaning, grammatical form.

- •2. Grammatical category.

- •1. A word and a morpheme. The notion of allomorphs.

- •2. Synthetic means of form-building.

- •3. Analytical forms.

- •1. Principles of classification. Possible ways of the grammatical classification of the vocabulary.

- •2. Notional and functional (formal) parts of speech.

- •1. General characteristics. Classification.

- •2. Morphological categories (number, case).

- •3. The problem of the category of article determination.

- •1. Time and linguistic means of its expression. Tense in Russian and English compared.

- •2. The problem of the future and future-in-the-past. The category of posteriority (prospect).

- •3. The place of continuous forms-in the system of the verb. The category of aspect.

- •If 4. The place of perfect forms in the system of the verb. The category of order (correlation, retrospect, taxis).

- •This opposition reveals a special category, the category of posteriority (prospect). Will come, denotes absolute posteriority, would come — relative posteriority.

- •Topic VII Verb.The Category of Voice

- •Topic VIII Verb. The Category of Mood

- •1. General characteristics.

- •2. Imperative.

- •3. The problems of subjunctive.

- •Topic IX

- •Topic X Sentence

- •John wrote a letter. Nvn — spo John had a snack. Nvn — sp

- •Literature

Literature

Blokh M.Y. A Course in Theoretical English C7rammar. M., 1983.

Chafe W. Meamng and the Structure of Language. Chicago-London, 1970 (русский перевод: У.Л.Чейф. Значение и структура языка. М., 1975.)

Chomsky N. Syntactic Structures. The Hague: Mouton, 1957 (русский перевод: Н.Хомский. Синтаксические структуры // Новое в лингвистике, вып. II, М., 1962.)

Chomsky N. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press Cambridge (Mass), 1965 (русский перевод: Н.Хомский. Аспекты теории синтаксиса. М., 1972.)

Fillmore Ch. The Case for Case // Universals of Linguistic Theory. NY, 1968 (русский перевод: Ч.Филлмор. Дело о падеже // Новое в зарубежной лингвистике, вып. X, М., 1981.)

Fillmore Ch. The Case for Case Reopened // Syntax and Semantics, vol. 8. NY, 1977 (русский перевод: Ч.Филлмор. Дело о падеже открывается вновь // Новое в зарубежной лингвистике, вып. X, М., 1981.)

Fries Ch. The Structure of English. NY, 1956.

Grice H.P. Logic and Conversation // Syntax and Semantics, vol. 3. NY, 1975 (русский перевод: Г.П.Грайс. Логика и речевое общение // Новое в зарубежной лингвистике, вып. 16, М., 1985.)

llyish В.A. The Structure of Modem English. Leningrad, 1971.

«

Jespersen 0. Essentials of English Grammar. London, 1933. Jespersen 0. The Philosophy of Grammar. London, 1935. Quirk R.. Greenbaum S., Leech G., Svartvik J. A University Grammar of English. M., 1982.

14

Sweet H. New English Grammar. Oxford, 1900.

55

Бархударов Л.С. Структура простого предложения современного английского языка. М., 1966.

Бархударов Л.С. Очерки по морфологии современного английского языка. М., 1975.

Воронцова Г.Н. Очерки по грамматике английского языка. М., 1960.

Смирницкий А.И. Синтаксис английского языка. М., 1957.

Смирницкий А.И. Морфология английского языка. М., 1959.

Шевякова В.Е. Современный английский язык. М., 1980.

CONTENTS

Topic I. Introduction to the Theory of Grammar................... 3

Topic II. Main Notions of Grammar....................................... 5

Topic III. The Structure of Words. Means of Form-Building....... 8

Topic IV. Parts of Speech..................................................... 11

Topic V. Noun................................................................... 14

Topic VI. Verb. Categories of Tense, Aspect, Order

(Correlation)......................................................... 18

Topic VII. The Category of Voice............................................. 22

Topic VIII. The Category of Mood............................................ 26

Topic IX, Syntax. Phrase....................................................... 31

Topic X. Sentence................................................................ 35

Topic XI. Sentence. Syntactic Structure. Models of Analysis......... 38

Topic XII. Sentence. Semantic Structure. Logico-Communicative

Structure.............................................................. 44

Topic XIII.'Composite Sentence. Sentence in the Text................. 49

LITERATURE . .. 55

20 • DISCOURSE AND TEXT

The traditional concern oflinguistic analysis has been the construction of sentences (§ 16); but in recent years there has been an increasing interest in analysing the way sentences work in sequence to produce coherent stretches of language.

Two main approaches have developed. Discourse analysis focuses on the structure of naturally occurring spoken language, as found in such 'discourses' as conversations, interviews, commentaries, and speeches. Text analysis focuses on the structure of written language, as found in such 'texts' as essays, notices, road signs, and chapters. But this distinction is not clear-cut, and there have been many other uses of these labels. In particular, both 'discourse' and 'text' can be used in a much broader sense to include all language units with a definable communicative function, whether spoken or written. Some scholars talk about 'spoken and written discourse'; others about 'spoken and written text'. In Europe, the term text linguistics is often used for the study of the linguistic principles governing the structure of all forms of text.

The search for larger linguistic units and structures has been pursued by scholars from many disciplines. Linguists investigate the features of language that bind sentences when they are used in sequence. Ethnographers and sociologists study the structure of social interaction, especially as manifested in the way people enter into dialogue. Anthropologists analyse the structure of myths and folk-tales. Psychologists carry out experiments on the mental processes underlying comprehension. And further contributions have come from those concerned with artificial intelligence, rhetoric, philosophy, and style (§12).

These approaches have a common concern: they stress the need to see language as a dynamic, social, interactive phenomenon - whether between speaker and listener, or writer and reader. It is argued that meaning is conveyed not by single sentences but by mote complex excVianges, in whicb tbe participants' beliefs and expectations, tbe knowledge they sbate about eacb otber and about tbe world, and tbe situation in wbicb tbey intetact, play a crucial patt.

CONVERSATION

Of the many types of communicative act, most study has been devoted to conversation, seen as the most fundamental and pervasive means of conducting human affairs (p. 52). These very characteristics, however, complicate any investigation. Because people interact linguistically in such a wide range of social situations,

on such a variety of topics, and with such an unpre-dicrable set of participants, it has proved very difficult to determine the extent to which conversational behaviour is systematic, and to generalize about it.

There is now no doubt that such a system exists. Conversation turns out, upon analysis, to be a highly structured activity, in which people tacitly operate with a set of basic conventions. A comparison has even been drawn with games such as chess: conversations, it seems, can be thought of as having an opening, a middle, and an end game. The participants make their moves and often seem to follow certain rules as the dialogue proceeds. But the analogy ends there. A successful conversation is not a game: it is no more than a mutually satisfying linguistic exchange. Few rules are ever stated explicitly (some exceptions are 'Don't interrupt!', and 'Look at me when I talk to you'). Furthermore, apart from in certain types of argument and debate, there are no winners.

Conversational success

For a conversation to be successful, in most social contexts, the participants need to feel they are contributing something to it and are getting something out of it. For this to happen, certain conditions must apply. Everyone must have an opportunity to speak: no one should be monopolizing or constantly interrupting. The participants need to make their roles clear, especially if there are several possibilities (e.g. 'Speaking as a mother / linguist / Catholic ...'). They need to have a sense of when to speak or stay silent; when to proffer information or hold it back; when to stay aloof or become involved. They need to develop a mutual tolerance, to allow for speaker unclarity and listener inattention: perfect expression and comprehension are rare, and the success of a dialogue largely depends on people recognizing tbeir communicative weaknesses, through the use of rephrasing (e.g. 'Let me put tbat anotber way) and clarification (e.g. 'Are you witb me?").

Tbete is a gteat deal of ritual in conversation, especially at tbe beginning and end, and wben topics change. For example, people cannot simply leave a conversation at any random point, unless they wish to be considered socially inept or ill-mannered. They have to choose their point of departure (such as the moment when a topic changes) or construct a special reason for leaving. Routines for concluding a conversation are particularly complex, and cooperation is crucial if it is not to end abruptly, or in an embarrassed silence. The parties may prepare for their departure a

CONVERSATION ANALYSIS

In recent years, the phrase 'conversation analysis' has come to be used as the name of a particular method of studying conversational structure, based on the techniques of the American sociological movement of the 1970s known as ethnomethodology.

The emphasis in previous sociological research had been deductive and quantitative, focusing on general questions of. social structure. The new name Was chosen to reflect a fresh direction of study, which would focus on the techniques (or 'methods') used by people themselves (oddly referred to as 'ethnic'), when they are actually engaged in social - and thus linguistic — interaction. The central concern was to determine how individuals experience, make sense of, and report their interactions.

In conversation analysis, the data thus consist of tape recordings of natural conversation, and their associated transcriptions. These are then systematically analysed to determine what properties govern the way in which a conversation proceeds. The approach emphasizes the need for empirical, inductive work, and in this it is sometimes contrasted with 'discourse analysis', which has often been more concerned with formal methods of analysis (such as the nature of the rules governing the

structure of texts).

20 • DISCOURSE AND TEXT

119

TEXTUAL STRUCTURE

To call a sequence of sentences a 'text' is to imply that ithe sentences display some kind of mutual dependence; they are not occurring at random. Sometimes the internal structure of a text is immediately apparent, as in the headings of a restaurant menu; sometimes it has to be carefully demonstrated, as in the network of '. relationships that enter into a literary work. In all cases, the task of textual analysis is to identify the linguistic features that cause the sentence sequence to 'cohere' -something that happens whenever the interpretation ofone feature is dependent upon another elsewhere in the sequence. The ties that bind a text together are often referred to under the heading of cohesion (after M.A. K. Halliday & R. Hasan, 1976). Several types of cohesive factor have been recognized:

^Conjunctive relations What is about to be said is explicitly related to what has been said before, through such notions as contrast, result, and time:

I left early. However, Jean stayed till the end. Lastly, there's the question of cost.

1 Conference Features that cannot be semantically interpreted without referring to some other feature in the text. Two types of relationship are recognized: jnuphoric relations look backwards for their interpretation, and cataphoric relations look forwards:

Stvemlpeople approached. They seemed angry. Listen to this: John's getting married.

' Substitution One feature replaces a previous expression:

I've got a pencil. Do you have one? Will we get there on time? I think so.

' Ellipsis A piece of structure is omitted, and can be recovered only from the preceding discourse:

Where did you see the car* л In the street.

• Repeated forms An expression is repeated in whole or

in part:

Canon Brown arrived. Canon Brown was cross.

j • lexical relationships One lexical item enters into a structural relationship with another (p. 105):

The/owmwere lovely. She liked the tulipsbest.

• Comparison A compared expression is presupposed in the previous discourse:

That house was bad. This one's far worse.

Cohesive links go a long way towards explaining how the sentences of a text hang together, but they do not tell the whole story. It is possible to invent a sentence

sequence that is highly cohesive but nonetheless incoherent (after N. E. Enkvist, 1978, p. 110):

A week has seven days. Every day\ feed my cat. Gztthave four legs. The cat is on the mat. Mathas three letters.

A text plainly has to be coherent as well as cohesive, in that the concepts and relationships expressed should be relevant to each other, thus enabling us to make plausible inferences about the underlying meaning.

TWO WAYS OF DEMONSTRATING COHESION

Paragraphs are often highly cohesive entities. The cohesive ties can stand out very clearly if the sentences are shuffled into a random order. It may even be possible to reconstitute the original sequence solely by considering the nature of these ties, as in the following case:

1. However, nobody had seen one for months.

2. He thought he saw a shape in the bushes.

3. Mary had told him about the foxes.

4. John looked out of the window.

5. Could it be a fox?

(The original sequence was 4,2,5,3,1.)

We can use graphological devices to indicate the patterns of cohesion within a text. Here is the closing paragraph of James Joyce's short story 'A Painful Case'. The sequence of pronouns, the anaphoric definite articles, and the repeated phrases are the main cohesive features between the clauses and sentences. Several of course refer back to previous parts of the story, thus making this paragraph, out of context, impossible to understand.

He turned back the way he had come, the rhythm of the engine pounding in his ears. He began to doubt the reality of what memory told him. He halted under a tree and allowed the rhythm to die away. He' could not feel her near him in the DARKNESS nor her voice touch his ear. He waited for some minutes listening. He could hear NOTHING: the NIGHT was perfectly silent. He listened again: perfectly silent.

He felt that he was ALONE.

MACROSTRUCTURES

Not all textual analysis starts with small units and works from the 'bottom up' (p. 71); some approaches aim to make very general statements about the macro-structure of a text. In psy-cholinguistics, for example, attempts have been made to analyse narratives into schematic outlines that represent the elements in a story that readers remember. These schemata have been called 'story-grammars' (though this is an unusually broad sense of the term 'grammar', cf §16).

In one such approach (after P. W. Thorndyke, 1977), simple narratives are analysed into four components: setting, theme, plot, and resolution. The setting has three components: the characters, a location, and a time. The theme consists of an event and a goal. The plot consists of various episodes, each with its own goal and outcome. Using distinctions of this kind, simple stories are analysed into these components, to see whether the same kinds of structure can be found in each (p. 79). Certain similarities do quickly emerge; but when complex narratives are studied, it proves difficult to devise more detailed categories that are capable of generalization, and analysis becomes increasingly arbitrary.

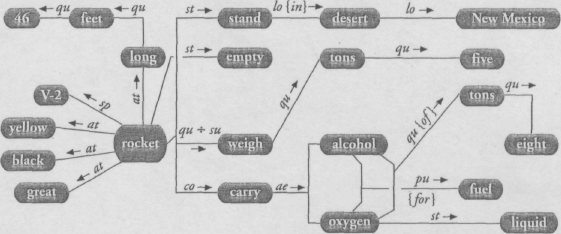

Conceptual structure One

way of representing the conceptual structure of a text (after R. de Beaugrande &W. Dressier, 1981, p. 100).. This 'transition network' summarizes the following paragraph:

A great black and yellow V-2 rocket 46 feet long

stood in a New Mexico desert. Empty, it weighed five tons. For fuel it carried eight tons of alcohol and liquid oxygen.

The abbreviations identify the types of semantic links which relate the concepts (following the direction of the arrows):

ae affected entity

at attribute of

со containment of

/o location of

pu purpose of

qu quantity of

sp specification of

st state of

su substance of

Topic 8 Units larger t h a n __a_cj a u s e

3. Text structure and its components (units).

Discourse is often defined in two ways: a particular unit of language (above the sentence), and a particular focus (on language use). These two definitions of discourse reflect the difference between formalist ъъ& functionalist paradigms. The two paradigms make different assumptions about the goals of a linguistic theory and methods for studying language. There is a third definition of discourse which attempts to bridge the formalist-functionalist dichotomy.

Opposite to a random sequence of sentences discourse has structure: it is comprised of units which occur relative to each other by a certain pattern. Recent approaches have identified the clause, the proposition, the sentence, the supra-phrasal unity, the paragraph, question-answer pair, the turn, the speech action as the unit of which discourse is comprised.

Several problems arise from the reliance of analysis on the 'sentence'. The first problem is that the units in which people speak do not always seem like sentences. The second problem is that the meaning of most of sentences depends on the context, i.e., they are not grammatically or semantically independent.

One way to get around some of these problems is to adopt the distinction between system-sentence and text-sentence. System sentences are abstract theoretical constructs, generated by the linguist's model; text-sentences are context-dependent utterance-signals. Another way to overcome the problems mentioned is to consider units larger than a sentence (supraphrasal unity or paragraph) to be text units. But the problem with the supraphrasal unity is that there are no distinct criteria for its identification: it can comprise one or more sentences, can be part of a paragraph, coincide with it or be longer than a paragraph.

Functionalism is based on two general assumptions: (a) language has functions that are external to the linguistic system itself; (b) external functions (e.g.. communicative concerns) influence the internal organization of the linguistic system. The functional analysis of discourse is the analysis of language in use. As such, it cannot be restricted to the description of linguistic forms independent of the purposes or functions of language in human life. These functions are not limited to tasks that can be accomplished to language alone; they can include tasks such as maintaining interaction or building social relationships.

The third approach which is taken in the book by D.Schiffrin is that discourse consists of utterances which are units of language production that are inherently contextualized. Discourse analysis based on that approach implies syntactic goals (investigating the principles of the order or arrangement of utterances) and semantic and pragmatic goals (studying the influence of the meaning and arrangement of discourse units on their communicative content).

- jf-

Трансформационная грамматика

1рансформационная грамматика - это одна из теорий описания естественного языка, основанная на предположении, что весь диапазон предложений любого языка может быть описан путем осуществления определенных изменений, или трансформаций, над неким набором базовых предложений. Разработанная Наумом Хомским (Noam Chomsky) в начале 50-х гг. и получившая свое развитие в ранних работах Зелига Харриса (Zellig Harris), теория трансформационной грамматики в настоящее время является чуть ли не единственной широко изучаемой и применяемой лингвистической моделью в США. В то же время необходимо отметить, что, в связи с возможностью по-разному трактовать большинство центральных идей данной теории, внутри нее в настоящий момент существует несколько соперничающих версий, претендующих на "правильную" интерпретацию трансформационной грамматики. Иногда трансформационную грамматику также называют генеративной грамматикой.

i Синтаксические и семантические правила

Центральная идея трансформационной теории состоит в том, что поверхностные формы любого

![]()

подсистемами. Большинство версий трансформационной грамматики предполагают, что две базовые подсистемы из их общего числа - это набор синтаксических правил (ограничений) и набор семантических правил. Синтаксические правила определяют правильное расположение слов в предложениях (например, предложение ' 36W vviii eat-uie *ct cream ирамишии, ии^-лилш^ vuvivmi *u именной группы "John" и следующей за ним глагольной группы, или предиката, "will eat the ice cream"). Семантические правила отвечают за то, чтобы правильно интерпретировать конкретное расположение слов в предложении (например, "Will John eat the ice cream" является вопросом).

Синтаксические правила можно далее разделить на jSajjpj^pjpAMjM^THKy, которая генерирует набор базовых предложений, и T^aHc^pj^aimjojHHHejnpaBHtJia, которые позволяют на основе базовых предложений создать производные предложения, или поверхностные структуры. Также существует дополни тельшгш НА^ с б дравил, которые на основе поверхностных структур создают произносимые выходные предложения.

Трансформационные правила

Трансформационные правила предназначены для описания систематических отношений в предложении, как то:

•отличия между активным и пассивным предложением

2

•глобальные отношения в предложении (например, связь между what и eat в предложении "What

will John eat")

•неоднозначности, причиной которых является одна и та же форма предложения, выведенная из двух различных базовых предложений (например, в предложении "They are flying planes" flying можно рассматривать и как прилагательное и как основной глагол)

Базовое предложение "John will eat the ice-cream" может быть сгенерировано простым набором синтаксических правил, а затем, применив к нему трансформационные правила, можно построить производный вопрос "Will John eat the ice-cream". С помощью другой последовательности трансформационных правил можно построить пассивное предложение: "Will the ice-cream be eaten by

---------- rt --- ~~.~._~ *.»*>.iut, ^iwiuwmui i/w it uv, a

ь'е z/ <6у , 'а тл^.^^ изменились местоположение и форма старых элементов предложения.

Правила базовой грамматики

I На выходе: базовые(глубинные) структуры -» Семантическая

интерпретация (значение) I

Трансформационные правила 4

На выходе: поверхностные структуры

I Фонологические правила

4 На выходе: звуковое представление

Наиболее общая схема трансформационной грамматики представлена на рисунке вверху. В данном обзоре мы рассмотрим подробно (кроме фонологического компонента) одну из версий трансформационной грамматики, так называемую стандартную теорию середины 60-х гг.

Базовая грамматика

Базовые синтаксические признаки описываются грамматикой непосредственных составляющих, в простейшем случае контекстно-независимой грамматикой. Данная грамматика имеет следующий набор правил:

1) S -> NP Aux VP 2) VP -> Verb NP

3) NP -> Name 4) NP -> Determiner Noun

5 } Auxiliary -> will 6) Verb -> eat

следует именная группал)Третье и|четвертое правило рассматривают именную группу, как имя собственное либо как существительное с детерминантом (определяемым словом). Последние пять правил являются лексическими; они вводят реальные слова, например, "".

Символы типа "ice cream" называются терминальными элементами, так как они никогда не присутствуют в левой части правил. К ним нельзя далее применять никакие правила; на них как бы заканчиваются все действия правил. Все остальные символы, такие как S, NP, VP, Name и другие, считаются нетерминальными.

Все правила этой грамматики называются jCffljrreKcrao-HjgaBHCHMbiMH, поскольку они позволяют свободно замещать любой символ слева от стрелки любой последовательностью символов справа от стрелки. С формальной точки зрения, контекстно-независимые правила имеют только один неразложимый символ, как то S. NP или VP, слева от стрелки.

правила грамматики, начиная с символа S и до тех пор, пока никакие правила уже нельзя применить. Этот процесс называется деривацией, поскольку из символа(8 выводится новая цепочка символов. Результатом деривационного процесса может служить следующая запись:

Как правило, системы правил, подобные вышеописанной, подвергаются расширению с целью исключить возможность генерации бессмыслицы, типа "The ice cream ate" или "John took". Для этого вводятся так называемые (Контекстно-зависимые правила, которые определяют контекст, дающий право заменять нетерминальные символы на терминальные. Например, символ V может быть заменен глаголом "took" только в том случае, если справа от него находится объект NP. Еще один пример: глагол "eat" может употребляться только после одушевленного существительного, что и должны подчеркивать контекстно-зависимые правила. Необходимо отметить, что в стандартной трансформационной теории 1965 года контекстно-зависимые лексические правила являлись частью словаря, а не базовой грамматики. В дополнение к лексическим контекстно-зависимым правилам, словарь содержит набор импликаций типа: "Если слово является именем человека, то оно также является одушевленным существительным."

Словарь, состоящий из лексических ограничений и правил импликации, в сочетании с правилами базовой грамматики позволяет генерировать определенный набор базовых предложений.

4 Ранее они назывались глубинными структурами, однако потом такая терминология была признана

неудачной: данные формы не являются глубинными ни в том смысле, что они являются наиболее простыми и неразложимыми, ни в том смысле, что их значение является более глубоким; вследствие этого было решено отказаться от данной терминологии.

Трансформационный компонент

В соответствии с блок-схемой, базовые структуры далее поступают в трансформационный компонент, где для генерации дополнительных предложений могут применяться от нуля до нескольких трансформаций; на выходе этой процедуры получается поверхностная структура, которую уже можно произносить, как обычное предложение. Если не применяется ни одно из трансформационных правил, то поверхностная структура получается такой же, как и базовое предложение. Такое обычно происходит с простыми повествовательными предложениями, например:. Если же трансформационные правила все же применяются, то они производят новые синтаксические признаки, например: "Will John eat the icecream".

Примером трансформационного правила может служить преобразование, создающее вопросительное предложение из синтаксического признака, который можно записать как X wh Y, где X и Y - любые цепочки символов в синтаксических признаках, a wh - - любая фраза, начинающаяся с wh, например, "who", "what" или "what ice cream". Цель этого трансформационного правила - переместить элемент wh в начало предложения. Если взять синтаксический признак, соответствующий предложению "John will eat what", то его часть, соответствующая "John will eat" будет равна X, "what" - wh, а пустая последовательность - Y. Можно сделать вывод, что данная трансформация может иметь место. Переместив фразу с wh в начало, мы получим "What John will eat". Применив к получившемуся синтаксическому признаку ^дополнительную трансформацию, а именно инверсию подлежащее -вспомогательный глагол, можно получить вопрос "What will John eat". Необходимо отметить, что трансформационные правила применимы только к целым предложениям.

Традиционно, структурные описания и структурные изменения записываются путем присвоения элементам правила порядковых номеров и соответствующей записи. В нашем случае правило wh будет записано следующим образом:

Структурное описание: (X,wh.Y)

(1:2,3)

Структурное изменение: (2,3,1)