Types of Nomination and Motivation of Lexical Units

As it follows from what has been said above the word is characterized by complexity. It involves various aspects and relations. The word denotes an object and gives a name to it, it has some sense, i.e. it signifies something, the sense, or content represents certain properties, or qualities of the object in people’s minds.

The outer facet (external structure, plane of expression), the phonetic and graphical shape of the word, is the sign of its sense – inner facet (internal structure, plane of content). The word as the unity of its outer and inner facets represents the object, or referent.

The word’s relation to object, its being a sign makes it possible to use words for giving names to things, phenomena, qualities, actions, etc. Words come into being when there is a need to give names to things. Hence the main function of the word is nominating. “... Nоmination is the process of converting the facts of extra-linguistic reality to the facts of language-as-a-system, its structure and meanings reflecting the human experience in the people’s minds” [Языковая номинация I 1977: 13]. Onomasiology is the science of names, the nature and types of nomination.

The peculiarity of the nominative aspect of the language is first of all that the linguistic signs, unlike all other ones, have twofold reference to the objects: 1) as nominative signs – words and word combinations – in language-as-a-system, its paradigmatic relations; 2) as predicative signs – phrases or utterances – in actual speech – language-in-action, its syntagmatic relations [Языковая номинация I, 1977:8].

There are distinguished the following types of nomination according to the language units employed in each case: a) lexical nomination – nomination by word, phraseological unit or word combinations; b) propositional nomination – nomination by sentence; c) discourse nomination – nomination by text.

The objects of lexical nomination, or nominants are such elements of reality as object (thing), quality (property), process, relations, any real or imaginary object. Nominants make up a system, nomenclature, which along with some semantic and functional peculiarities, serves as the basis of subdividing all the words primarily into the classes of notional and formal words.

Further on the notional words are subdivided according to the qualitative characterization of the objects into those naming the objects (substantival) – the nouns; and those naming the features, or manifestations of the objects – the verbs, naming processes, actions and states; the adjectives, naming qualities and properties; the adverbs, naming certain circumstances and conditions. The quantitative characterization of the objects is realized by numerals. Pronouns, prepositions, connectives, conjunctions, particles, articles refer to formal words. Thus the elements of nomination form the basis for the main classes of words – the categories of parts of speech, known since the times of Aristotle.

The object of propositional nomination by sentence is a microsituation (an event, a fact), involving certain substances and elements.

The object of discourse nomination – nomination by text – is a more complicated string of situations.

The complexity of nominating means increases with the increase of the complexity of the nominated object. More complex nominations (word combinations, sentences and texts) are constructed by combinations of words – the initial and simple nominating units.

The nominant of the sentence, or utterance, is a complex referent, a certain interrelation of real phenomena (objects, qualities, processes) in various combinations. Even the simplest sentence, e.g. The child is playing presents a combination of two elements: the agent of the action and the action itself.

Text is a complex multi-structural integrity arranged in accordance with the communicative intention, genre specifics. The nominants of the text are information blocks.

A new name comes into being when a certain sound complex is associated with meaning. This meaning refers to some fragment of extra-linguistic reality, a new object, phenomenon, quality, action, etc. When such act of nomination happens for the first time it is known as direct or primary nomination. By primary lexical nomination is understood the interrelation of a fragment of extra-linguistic reality reflected in one’s mind and the sound complex, which has got the function of a name for the first time [Языковая номинация I 1977: 73]. Such primary meanings of the words were called by Academician V.V.Vinogradov ‘direct nominative meaning’.

There is a constant need in new names with new developments in the life of speech communities. The process of nomination is endless. But it is impossible to create an entirely new name for each new object, phenomenon, etc. It would make the language system too bulky and unmanageable. Human memory would not be able to cope with such a great amount of names. That is why a name of a certain object can be used for naming another object, phenomenon, quality, action, etc. Secondary / indirect nomination is using the name of one object for naming another object. Of course, secondary nomination cannot be done at random. There must be something in common between the two objects, certain associations (of similarity or contiguity, see ch. 2).

For example the word ‘hand’ in its primary function means 1) part of the human arm beyond the wrist. As a result of secondary nomination it got the meanings: 2) (pl) power, possession, responsibility: The property is no longer in my hands; 3) influence or agency: The hand of an enemy has worked here; 4) person from whom news, etc. comes: I heard the news at first hand; 5) skill in using one’s hands: She has a light hand at pastry; 6) person who does what is indicated by the context, performer: He is a good hand at this sort of work; 7) workman, e.g. in a factory or dockyard: All hands on deck!; 8) turn, share in an activity: Let me have a hand now; 9) pointer or indicator on the dial of a watch, clock or other instrument: hands of a watch; 10)position or direction (to right or left): on all hands 11) handwriting: He writes a good hand and other meanings. The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English by A.S.Hornby registers 16 meanings of this word and many derivatives and idioms with ‘hand’. This is an example of language economy and flexibility.

To cases of secondary lexical nomination also refer lexemes, coined by compounding, joining together two derivational bases (see ch. 4): such as arm-chair, keyhole, red-haired, affixation (coining words by means of derivational affixes): uneasy, kindness, musician and also many other words coined by various means of word-formation. Secondary nomination plays a very important role in language functioning as it a) enables to use the means available in the language for giving a name to an object that had no name before, e.g. a mouse ‘device used to control a cursor on a computer monitor’; b) creates a stylistic effect: lexical stylistic devices such as metaphor, metonymy, irony and others are based on making use of already existing names to characterize some other objects, for instance, names of animals can be used to characterize people possessing some negative traits: cat ‘excitable woman’, goose ‘simpleton’; c) provides the means for functioning of various communicative types of sentences: the usage of the verbs be, have, do etc. as auxiliaries.

The relation between the external structure of the word (its phonetic shape, morphological composition, structural pattern) and its meaning is called motivation. Three basic kinds of motivation are distinguished: phonetic, morphological and semantic.

To phonetically motivated words refer examples as bang, buzz, cuckoo, giggle, gurgle, hiss, purr, whistle, etc., i.e. onomatopoetic words. Such words are phonetically motivated because there can be traced the relation between the sound form of the word and its meaning, they are coined by imitation of natural sounds.

To morphologically motivated words refer lexical units with a complex morphological structure, i.e. consisting of more than one morpheme. The meaning of such words can be deduced from the meanings of the morphemes constituting them and the structural pattern which determines the order of the components. For example, the word reread is morphologically motivated inasmuch as its meaning can be deduced from the meanings of its component morphemes and the structural pattern. This is the case with affixal derivatives and compound words like: winner, coolness, employee, mispronounce, discomfort, hairdo, nightwatch, theatre-goer, sky-blue, etc.

Semantic motivation is conditioned by the synchronic co-existence of the direct nominative and nominative-derivative meanings. The word is semantically motivated if its derivative meaning (metaphoric, metonymical) is perceived through the direct nominative one. For instance the word head in the contexts Heads or tales?, the head of the family, at the head of the page is semantically motivated inasmuch as its meaning is perceived through the direct nominative meaning of this word. Unlike the phonetic motivation, the morphological and semantic motivations are relative as the direct nominative meanings of the word and meanings of morphemes are not motivated.

If there cannot be traced the connection between the phonetic or morphological structure of the word and its meaning or the direct and derivative meanings of the word, the word is unmotivated. The overwhelming majority of simple non-derivative words are like cat, dog, man, girl, good, young, take, read, etc. are unmotivated. It is considered that initially such words were motivated but in the course of time motivation was lost.

The Notion of Lexeme. Variants of Words

Besides the term ‘word’ there exists a scientific term lexeme. This term emerged from the necessity to differentiate a word-form and the word as a structural element of the language. Thus in the sentence My friend has got a lot of books and I borrowed an interesting book from him the words books and book are perceived as two words but actually these are the grammatical variants of one lexeme. The term lexeme was introduced to avoid such kind of ambiguity. Besides it is in line with the terms of units of other levels: phoneme, morpheme, phraseme.

Lexeme is a structural element of the language, word in all its meanings and forms (variants). Lexeme is an invariant (from Lat. invarians ‘unchangeable’), i.e. “the common property inherent in classes of relatively homogeneous classes of objects and phenomena” (Сoлнцев, p. 214). This common property is realized in all the variants of a lexeme’s use in actual speech.

When used in actual speech the word undergoes certain modifications and functions in one of its grammatical forms, e.g. singer, singer’s, singers, singers’ (He is a good singer. I like the singer’s voice, etc.) or to take, takes, took, took, taking. Grammatical forms of words are called word-forms, or grammatical variants of words. In the above example these are variants of the lexemes singer and take. The system showing a word in all its word-forms is called its paradigm. The lexical meaning of the word remains unchanged throughout its paradigm. All the word-forms are lexically identical but they differ in their grammatical meanings. Actually in each particular context we deal with particular grammatical variants of lexemes.

Besides paradigms of particular words, such as boy, boy’s, boys, boys’ there is an abstract notion of paradigms of parts of speech. For instance, the paradigm of the noun is ( ), (-’s), (-s), (-s’), the paradigm of the verb is ( ), -s, -ed, -ed, -ing. The sign ( ) stands for a zero morpheme, i.e. its meaningful absence.

Besides the grammatical forms (variants) of words, lexical varieties of the word are distinguished, which are called lexico-semantic variants (LSVs). The overwhelming majority of English words are polysemantic, i.e. they have more than one meaning but in actual speech a word is used in one of its meanings. Such a word used in oral or written speech in one of its meanings is called a lexico-semantic variant.

E.g. to call - 1) say in a loud voice: She called for help, 2) pay a short visit: I called on Mr. Green, 3) name: We call him Dick, 4) consider, regard as: I call that shame, 5) summon, send a message to: Please call a doctor. The verb to call is presented here by five LSVs.

Many lexemes have more than one variants of pronunciation. They are phonetic variants of lexemes. Phonetic variants are different ways of pronouncing certain lexemes, e.g. again [ə`gein, ə`gen], interesting [`intristiŋ, intə`restiŋ], often [`o:fn, `ofn, `ofən, `oftən], etc. There are also graphical variants, i.e. different ways of spelling one and the same lexeme: inquire/enquire.

To morphological variants belong the cases of certain differences in the morphological composition of words not accompanied by differences in meaning. These are the cases of the two variants of the Past Indefinite tense: to learn – learnt, learned, to leap – leapt, leaped; to spoil – spoilt, spoiled; to dream – dreamt, dreamed, to broadcast – broadcast, broadcasted, etc. Also to morphological variants belong parallel formations like: phonetic – phonetical, geologic – geological, etc. Phonetic and morphological variants are modifications of the same lexeme as the change in the composition of a word is not followed by a change in meaning. In case of different meanings we deal with different lexemes. Compare for instance economic 'экономический' and economical ‘экономный’ which are different lexemes.

Thus, within the language system the word or lexeme exists as a system and unity of all its forms and variants. It is an invariant – the structural unit of the language.

Referential and functional approaches to meaning.

Semasiology (Greek semasia ‘meaning’) is a branch of lexicology investigating meaning of language units. It is universally accepted that language units having meanings are morphemes (the smallest meaningful units), words (lexemes), word combinations (phrases), sentences. The problem of phonetic meaning is controversial [Журавлев 1974]. There is also the term semantics which refers to the content of language and speech units. It is used in the following word combinations: semantics of the word, semantics of the sentence, semantics of the text, etc. Also this term refers to logical semantics.

As it was mentioned above, meaning is the inner facet of the word as a linguistic sign, its content. The very function of the word as a unit of communication is made possible by its possessing a meaning. Besides, meaning is a linking element between the objects of extra-linguistic reality (also qualities, processes) and the sound sequences which are the names of the objects.

Therefore, meaning is the most important property of the word.

The problem of meaning has a long tradition in linguistics. Philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome were interested in relations between the name and the thing named and what role meaning plays in these relations.

There are two main approaches to the problem of meaning in modern linguistics: referential and functional.

The referential approach (or theory) has a long tradition. It proceeds from the assumption that the word as a name is related to a thing (object) it names, which is called a referent (denotatum). The word ‘referent’ allows twofold interpretation. It denotes either a certain object, quality, process (real or imaginary) in actual situations of speech as in sentences: ‘The pen is on the table’ or ‘The book is interesting’, or a class of objects as pen (a class of pens) different from pencil (a class of pencils) or table different from chair, etc. It means that the word has a generating function.

The classes of things having names are distinguished by certain features, or properties, inherent in them. These features make up the concept of the object in our minds. The generating function of the word is most obvious in such contexts as The dog is a domestic animal, where the objects named refer to a class.

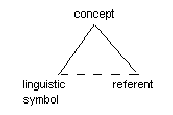

In order to give a name to an object, one should form the notion, or concept of it, i.e. one must know the salient features of the object which differentiate it from other objects. Hence there is interrelation between word (its outer facet - a sound or graphic form), concept and referent which is represented by the so-called semantic triangle offered by the British linguists C.K.Ogden and I.A.Richards [Ogden, Richards 1946]:

By ‘linguistic symbol’ here is meant the sound or graphic form of the word.

The dotted line suggests that there is no immediate relation between word and referent: it is established only through context.

Hence, meaning in referential approach is a component of the word through which a concept is communicated, in this way endowing the word with the ability of denoting objects, qualities, phenomena, actions and abstract notions. One should bear in mind that though meaning is related both to referent and concept, it is not identical to either of them.

Meaning is not identical to referent (denotatum) as the latter, be it a single object referred to, or a class of objects belongs to extra-linguistic reality while meaning is a linguistic category. One and the same object can be named by different words, having different meanings. A woman can be called mother, sister, lady, doctor, etc. Not every word is related to really existing objects, some of the referents are fantastic or imaginary ones (e.g. dragon, devil).

Meaning is neither identical to concept as the latter is a category of cognition, i.e. it is a mental but not a linguistic phenomenon. Concepts reflect general and prominent features of objects and phenomena while meanings mostly fix features differentiating objects. Concepts are more or less identical for peoples speaking different languages, but meanings may be different. For example, the concept of house is identical for people speaking English and Russian languages as it is ‘a place for human habitation’, but the Russian word дом has a wider volume of meaning than the English word house as it embraces meanings of both the words house and home.

Synonyms more often than not reflect one and the same concept but differ in components of meaning. Thus the concept which refers to the initial phase of certain activities is reflected in the meanings of synonymous lexemes to begin (to start, take the first step), to start (to begin to do sth., begin an action), to commence (formal – begin, start), to initiate (set a scheme, etc working), to inaugurate (introduce a new official at a special ceremony). Each of these synonyms has its own meaning which brings to light a certain aspect of the underlying concept.

The above-mentioned correlation of word, concept and referent underlies certain definitions of meaning. Though the users of the language freely operate with the notion of meaning, giving a satisfying definition to meaning is no less easy matter than giving a definition to the word due to complexity of both notions. Definitions based on relations of the word and the referent are called ostensive, or referential. Such definitions are illustrative. In fact an ostensive definition is pointing at the corresponding referent and this method of defining words is widely used in teaching languages.

Ostensive definitions, however, are not free of shortcomings. Mere pointing at the object is not enough to give a satisfying definition of the word. Besides, the meanings of such abstract nouns as, for example, beauty, idea, verbs and adjectives as think, interesting, conjunctions, etc. are impossible to define by pointing at their referents. Thus ostensive definitions are applicable only to a relatively limited number of words, the so-called denotative, or identifying words, i.e. the words referring to material objects. The so-called predicative, or characterizing names, referring to properties and manifestations of objects or relations between the objects, cannot be defined ostensively [Харитончик 1992: 31]

A number of conceptual definitions of meaning based on interrelations between the word and the concept were put forward by linguists. For instance V.V.Vinogradov defines “lexical meaning of the word as its conceptual content, which is formed according to grammatical norms of the given language and is an element of the lexico-semantic system of the language” [Виноградов 1953].

Professor A.I.Smirnitsky proceeded from the basic assumption of the objectivity of language and meaning, and understanding the linguistic sign as a two-facet unit. He defined meaning as “a certain reflection in our mind of objects, phenomena or relations (or imaginary constructions as mermaid, goblin, witch) that makes part of the linguistic sign – its so-called inner facet, whereas the sound form functions as its outer facet, its material shape...” [Смирницкий 1956: 152].

O.N.Sеliverstova defines meaning as information contained in the word [Селиверстова 1975].

Conceptual definitions were subject to criticism on the grounds that they are not purely linguistic and to a certain extent subjective. Besides some linguists claim that despite the obvious interrelation between the word meaning, the referent and the concept, it is not sufficient to elucidate the linguistic essence of the word meaning.

The functional approach aims at giving a purely linguistic definition of meaning thus overcoming the shortcomings of the above-mentioned definitions. According to this approach “meaning of the word is its functioning in speech” (Witgenstein) [Витгенштейн 1985].

This approach is based on the assumption that the meaning of a linguistic unit should be investigated in actual speech through its relations to other linguistic units and not through its relation to either concept or referent. For instance, the word black has different meanings in contexts: a black hat, black sorrow, Black Death.

The functional approach helps us determine meanings of words in different contexts. However, it would be erroneous to fully identify the meaning and function of the word. Contexts indicate the meaningful differences of word meanings, but words have meanings outside contexts and it is not always possible to determine word meaning without correlating the word with its referent no matter how many contexts of its usage might be produced [Харитончик 1992: 34].

The referential and functional approaches should not be opposed to one another. The best way to have better understanding of meaning would be using both approaches in combination. They supplement each other and will provide a deeper understanding of such a complex linguistic phenomenon as meaning.

At present one more trend in semantic theory initiated by foreign linguists W.Chafe, Ch.Fillmore, J.Lakoff, R.Jackendoff, R.Langacker and others is being developed within the cognitive linguistic theory which got the name of theory of prototypes. It proceeds from the cognitive function of the language. Language is a very important instrument of human cognition with the help of which people get knowledge of the world and fix the new facts they learn in the language. Linguistic categories are conceptual categories of cognition. The interpretation of semantic phenomena is based on the sense underlying the word meaning which comes to light in the course of human experience and is important for distinguishing one object from another.

The word meaning in the cognitive approach is treated as the prototype of the object it refers to. This understanding of word meaning proceeds from human experience and perception of the reality and tends to reflect the peculiarities of human cognition of the world. The prototype of the object is formed in the course of observations and experiments when a human being discovers certain cognitive, or prototypical features of objects which distinguish this object from others and make up its prototype. For example, in order to distinguish fish from other living creatures one must know that the fish are animals living in water having gills and fins, etc. – these are the prototypical features of the object which got the name of fish. This theory differs from other semantic theories inasmuch as it takes into account the human factor in the processes of cognition and the language.

Types of Meaning

Word meaning is not homogeneous but is made of various components, the combination and interrelation of which determine to a great extent the inner facet of the word. These components are described as types of meaning. The two main types of meaning are lexical and grammatical. In actual speech words impart simultaneously two main types of information: the information of the referent or concept the word relates to, and the information relevant for the word’s proper functioning in speech. The word cats, for instance, used in the sentence They have two cats expresses two kinds of meaning - the lexical one, denoting a certain kind of animal, and the grammatical one, denoting plurality.

The component of meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit, recurrent in all the forms of this word is described as its lexical meaning. This meaning serves to differentiate lexemes and it remains unchanged throughout the paradigm of the word (e.g. cat, cat’s, cats, cats’).

The grammatical meaning is defined as the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words [Ginzburg 1979:18]. Grammatical meaning is the meaning proper to grammatical classes or categories of words which embrace sets of word-forms common to all words of a certain class. For instance, the grammatical meaning of plurality can be expressed in the forms of various words irrespective of their lexical meaning: boys, books, cats, children, etc.; the tense meaning by asked, thought, walked, etc.

Сomparing lexical and grammatical meanings one cannot fail to notice that the lexical meaning is concrete and individual, sometimes it is called the material meaning of the word, while the grammatical meaning is much more abstract and generalized. The grammatical classes of words are singled out not only on the basis of the grammatical meaning but also certain formal features, e.g. the inflection -s for the plural of nouns, -ed for the Past Indefinite Tense. That’s why it is also called formal, or structural. However, it is not quite correct to say that the lexical meaning is only concrete and individual. The word through its lexical meaning also performs a generalizing function, as it nominates not only a particular individual object when used in a speech situation, but a class of objects as in the above-mentioned example, the word house in its lexical meaning ‘a place for human habitation’ is generalization from any particular building where people live. However, this generalization is of lower level compared with the generalizing power of the grammatical meaning which embraces not one class of objects.

Both the lexical and the grammatical meanings make up the word meaning as neither can exist without the other. Both of these meanings are formed simultaneously in the process of nomination. The object not only gets its name in the process of nomination but also is referred to a certain grammatical class. For example, a relatively new word computer imparts the information of the individual meaning of the word ‘electronic machine which calculates and keeps information automatically’ but also the meaning of substantivity, ‘thingness’ which refers the word to the class of nouns.

Lexemes are classified into major (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs) and minor (articles, prepositions, conjunctions, particles) word classes known as parts of speech. Classes of lexemes possess the part-of-speech meaning which includes lexical and grammatical components of meaning. A lexical component of part-of-speech meaning is very abstract and it is the component of meaning common to all the lexemes of the given part of speech. For instance, the part-of-speech meaning of nouns is ‘thingness’ or ‘substantivity’, adjectives - ‘quality’, verbs - ‘processes’. The grammatical aspect of the part-of-speech meaning is conveyed by a set of forms. If the lexeme is a noun, it is bound to possess a set of forms expressing the grammatical meaning of number (joy-joys), case (boy, boy's). A verb possesses grammatical meanings of tense, aspect, etc.

The interrelation of the grammatical and lexical meanings and the role each of them plays varies in different word classes and even in different groups of words within the same class. In minor word classes (articles, pronouns, conjunctions, etc.) grammatical meaning is prominent. The lexical meaning of prepositions may be comparatively distinct (in, on, under the table). In verbs the lexical meaning usually comes to the fore, although in some of them (to be, to have) the grammatical meaning of a linking element prevails.

Lexical meaning is not homogeneous. It is characterized by complexity which is stipulated by the complexity of the nomination processes and the multifarious character of communication.

The basis of the lexical meaning is the word’s reference, the ability of the word to be used for denoting the objects and phenomena of reality and also the objects and phenomena of cognition (thinking) [Беляевская 1987: 45]. The word’s reference forms its material content. The content of the word includes the denotational (denotative) and significative aspects (components) of meaning. Distinguishing of these aspects proceeds from understanding the word as a linguistic sign in the referential approach to meaning.

The word possesses the denotational aspect of meaning as it denotes things, phenomena, etc. It points at the word’s connection with the object or phenomenon of the reality. The denotational meaning makes communication possible. People understand each other’s speech because they know what words denote, i.e. their denotational meanings. The denotational component of meaning in most cases underlies dictionary definitions of words. For example, the denotational aspect of the word table reflects the features of the object of a certain type and having certain functions. The referent of the word table represents a particular class of objects. The prominent features and functions of the object are reflected in its definition: ‘piece of furniture consisting of a flat top with (usu. four) supports (called legs)’ (ALD).

The significative aspect of the lexical meaning of the word is the conceptual content of the word, its ability to reflect the corresponding concept underlying the word’s meaning. While investigating the lexical meaning which is formed in the process of nomination, it is important to determine the correlation between denotation and signification. The investigation of language material proves that here there are certain possibilities: the denotatum might come close to the concept, embracing the most significant features of the class of the objects or be much narrower than the concept [Беляевская 1987: 46]. There is an opposition between what the word signifies and what it denotes. “Signifying”, the word reflects the most common features (the concept) of the object named; “denoting”, the word fixes certain particular features of the object and it is related to the referent through denotation.

For instance, the English verb to sit is related to the concept of occupying a certain position in space (the significative aspect of the lexical meaning) but it denotes the position occupied only by people and some animals (the denotational aspect of meaning), unlike the Russian сидеть. Cf. Rus. : Пчела сидит на ветке. Пирог сидит в печи, which is rendered in English by the verb to be: The bee is on a twig. The pie is in the oven.

Along with the denotational and significative aspects of lexical meaning some words possess connotational and pragmatic aspects. Connotation is an additional component of meaning which contains information of the speaker’s emotional-evaluative attitude to things and phenomena (the emotive charge). The connotational component may be found in certain words along with the denotational one.

The emotive charge is one of the objective semantic features proper to words. There exist words containing positive or negative emotive evaluation. Comparing synonyms well-known – famous – notorious we observe that the word famous possesses a positive connotation, meaning someone who is ‘well-known for some good deeds or achievement’, while the word notorious ‘well known for doing sth. bad’ is marked by negative emotional-evaluative connotation. Thus, these three words have one and the same denotational component of meaning but differ in their connotations.

The connotational component of meaning includes such parameters as emotiveness, evaluation, intensity which in actual use are closely interwoven.

Emotiveness as a component of the connotational meaning presents the information of the emotional attitude to things or phenomena fixed up in the word meaning. Besides the above example of the synonyms, the emotive component can be found in the meanings of the words garish, showy. The denotational component of the lexical meaning of garish is ‘bright’. However, brightness implied by the word garish is unpleasant to eye, and this emotive connotation is fixed in the word’s dictionary definition ‘unpleasantly bright’, e.g. garish light, garish colours ‘over-coloured’, garish clothes ‘over-coloured or over-decorated’. Hence, the meaning of the word garish besides its denotational component contains a negative connotation. The word striking is marked by the positive emotive charge and is defined as ‘arousing great interest, drawing the attention, esp. because of being attractive or unusual’.

The evaluative component of connotation fixes in the lexical meaning of the word the information of positive or negative attitude (approval or disapproval) to objects or phenomena. Evaluation is subdivided into intellectual (logical) and emotional.

Positive intellectual evaluation is found in such words as hero, prodigy, to succeed etc. For example, in the definition of the word prodigy ‘person who has unusual or remarkable abilities or who is a remarkable example of sth.’ the italicized words are the components of meaning which express the positive intellectual evaluation. Negative intellectual evaluation is contained in the words like thief, liar, to deceive, to intrude, etc. For example, to deceive – cause (sb.) to believe sth. that is false.

Emotional evaluation also expresses positive or negative attitude to the object but in this case, however, the attitude is based not on the logical categories but emotions which are caused by the object, process or phenomenon which the word denotes. Emotional evaluation is contained in the meanings of the words to whine ‘make a high sad sound’, a smirk ‘silly proud smile’, to beam ‘(fig) smile happily, cheerfully’.

The emotive and evaluative components are so closely interwoven that sometimes it is rather difficult to differentiate them, so in most cases they are referred to as emotive-evaluative components.

By the same token the emotive and evaluative components are closely interwoven with the component of intensity which is another component of the connotational meaning. Intensity can be defined as the connotational component which denotes the measure of size, strength or depth of certain qualities of the object. It is present, for instance, in the words enormous, gigantic, huge as compared to words big, large where we observe different intensity of the quality ‘large’. Also comparing small and little with tiny and minute we observe different intensity of smallness. The interrelations of emotiveness and intensity can be traced in the set of words: to like, to love, to adore, to worship.

The pragmatic value of the word contains information of the participants and conditions of the speech situation which is also an additional component to the denotational meaning. For instance, the lexical meaning of the word contains information of whether the word belongs to neutral, formal, informal registers or styles of the language; also to slang, jargon, poetic, archaic words – that is the stylistic reference of the word. Compare words child (neutral), kid (informal), infant (formal). The status of participants of a speech situation is identified by the words they use. Certain words used by the speaker might point to his/her territorial appurtenance. For instance, if someone uses words subway, candy, elevator, he/she uses words belonging to American English and might be an American, contrary to British English underground, sweets, lift used by the British. Here also belong dialectal words, e.g. bonny ‘pretty’, wee ‘small’, lass ‘girl’ used by those speaking the Scotch dialect.

The pragmatic aspect of the lexical meaning includes information of the role a speaker plays in particular speech situations which occur in the course of various contacts and interrelations of the communicators, such as friendly, informal, formal, the relations which reflect attitudes of people to each other: respect, politeness, subordination, etc. For instance, hi and hello belong to the formal register and signalize of friendly relations between the communicators.

The information of the communicators relating to the pragmatic aspect of the word meaning may also concern the so-called stratificational status of the communicators: age (a little child would call his mother mummy; a teenager mum, mom), gender (e.g. the exclamations Lovely! Terrific! Admirable! are more often used by women), education, social status.

And finally, one more constituent of the pragmatic aspect points to the professional sphere the speaker belongs to. If he uses such words as e.g. larceny ‘an act of stealing’, to indict ‘to accuse’, he might be a lawyer, or the one using words like neutron, positron, etc. might be a physicist.

The components of the pragmatic aspect are also closely related as is the case of other components of the connotational meaning, and in the majority of cases combinations of various pragmatic factors are observed in the meaning of one and the same lexeme. All the aspects of the lexical meaning of the word are interconnected and might be singled out only for descriptive purposes. They make up a single structure, which determines the systematic and functional properties of the word.

Causes, types and results of semantic change.

Word-meaning is liable to change in the course of the historical evolution of the language. Changes of lexical meaning are determined by diachronic semantic analyses of many commonly used English words. Thus the word silly (OE sælig) meant ‘happy’, the word glad (OE glæd) had the meaning of ‘bright, shining’, etc. Polysemy is the result of semantic change, when new LSVs emerge on the basis of already existing ones according to certain patterns of semantic derivation.

It is necessary to discriminate between the causes, the nature and the results of semantic change. Discussing the causes of semantic change we attempt to find out why the word changed its meaning. The factors accounting for semantic changes are of two kinds: a) extra-linguistic and b) linguistic causes. By extra-linguistic causes are meant changes in the life of a speech community, various spheres of human activities as reflected in word meanings. Historical, economic, political, cultural, technological, etc. changes result in either appearance of new objects which require new names or the existing objects undergo changes to such an extent that it causes semantic changes. Although objects, concepts, institutions, etc. change in the course of time, in many cases the sound form of the word is retained. The word car from Latin carrus which meant ‘a four-wheeled wagon’ now denotes ‘a motor-car’ and ‘a railway carriage’. The meaning of the word ship (OE scip) also considerably changed from the primary ‘vessel with bowsprit and three, four or five square-rigged masts’ to modern ‘any sea-going vessel of considerable size’ and ‘spacecraft’.

Social factors play a very important part in semantic change, especially when the words become jargonisms and professionalisms, i.e. used by certain social or professional groups. Each group uses its own denominations, and in consequence words acquire new content, new LSVs emerge, developing the words’ polysemy. Such are the polysemantic lexemes ring and pipe. The lexeme ring developed such professionalisms as ‘circular enclosure of space for circus-riding’, ‘concentric circles of wood when the trunk is cut across’, ‘space for the showing of cattle, dogs, etc (at farming exhibitions, etc) and others; pipe ‘musical wind instrument’, geol. cylindrical vein of ore, ‘cask for wine, esp. as measure’ and others.

To linguistic causes of semantic change refer changes of meaning due to factors acting within the language system. They are as follows: a) ellipsis: in a phrase made up of two words one of these is omitted and its meaning is transferred to another, e.g. the meaning of the word daily was habitually used in collocation with the word newspaper. Later the noun newspaper was omitted and the adjective daily acquired the meaning of the whole phrase ‘daily newspaper’; b) discrimination of synonyms: when a new word is borrowed or coined in the language, it sometimes influences meanings of its synonyms, e.g. the Old English word hlaf which had the meaning of modern bread changed its meaning under the influence of the word bread, and now the OE hlaf is loaf which means ‘mass of bread cooked as a separate quantity’; the word fowl (OE fugol) had the meaning of modern bird but under the influence of its synonym bird [OE brid ‘young bird’] the word fowl developed a new LSV ‘domestic cock or hen’; c) linguistic analogy: it was found out, that if one of the members of a synonymic set acquires a new meaning, other members of this set change their meaning too, for instance, verbs synonymous with catch, e.g. grasp, get, etc. acquired another meaning - ‘to understand’ [Ginzburg 1979: 29].

Change of meaning presupposes using the existing name of a certain particular object for nominating another object. Such processes lately have got the name of secondary nomination. The processes of secondary nomination are also called transference of meaning, though it is more correct to speak of the transference of names and emerging of new meanings.

Changes in meaning become possible because there is a certain connection, association between the old meaning and the new or the two objects (referents) involved in the processes of nomination. Associations of meanings reflect our perception and understanding of things. There are two main types of association involved in semantic change: similarity of meanings and contiguity of meanings.

A very productive type of semantic change is metaphor which is based on similarity of meanings. This is a semantic process of associating two referents, one of which in some ways resembles the other. Similarity of meaning may be based on different aspects of objects: similarity of their forms - the nose of a kettle, the bridge of the nose, the lip of a crater, the eye of a potato; similarity of position in space - the leg of the table, the foot of the hill, the mouth of a river, etc. In many languages there are regular patterns which serve as basis for metaphoric transference. The above examples illustrate the most obvious pattern of transfer of terms for parts of the human body to external objects in nature. Another obvious pattern is the case when names of animals through metaphoric transference are used to give names to people whose behaviour resembles that of animals, e.g. cat – (fig.) an excitable woman, goose – simpleton, cow – awkward woman, cuckoo – crazy person, chicken – coward etc.

A subtype of metaphoric transferences is the so-called synesthesia. Synesthetic transferences are based on similarities of the physical and emotional perception of two objects. Adjectives denoting physical properties (temperature, light, size, taste, etc.) come to denote emotional or intellectual properties: a sharp smell, a warm feeling, a cold reception, a sharp pain, soft music, a bright idea, etc. Within verbs synesthetic transferences are observed in lexemes denoting physical qualities which come to denote emotions and intellectual activity: to grate ‘have an irritating effect’, to rasp on one’s nerves ‘to annoy’, to crack a code ‘to decipher a code’, to smash a theory ‘to disprove a theory’.

The above examples in no way exhaust all the multitude of metaphoric transferences, which result in appearance of many new LSVs in polysemantic lexemes. The role of metaphor is extremely important in the processes of cognition and nomination. In their book “Metaphors We Live By” [Lakoff, Johnson 1980] the authors contend that metaphor is not only a language phenomenon but also a daily conceptual reality when we are thinking about one sphere in the terms of another one. Based on similarity of objects, metaphor is closely linked with man’s cognitive activity, as it presupposes cognition through comparing objects.

Metonymy or contiguity of meanings may be described as the semantic process of associating two referents, one of which makes part of the other or is closely connected with it. There are various patterns of metonymy based on spatial, temporal relations, relations of cause and result.

There are distinguished certain patterns of metonymic transferences. Thus, to examples of metonymy based on spatial relations belongs the pattern when people or objects placed in the proximity of some other object, on or within the object get the name of that object. In the sentence Keep the table amused, the word table denotes people sitting around the table. In the example The hall applauded people got the name hall according to their location inside the hall at the moment. This pattern of spatial relations can be described as the relations between ‘the container and the thing contained’.

In the semantic structure of the lexeme school we find the following LSVs: school - 1) institution for educating children; 2) process of being educated in a school: Is he old enough for school?; 3) time when teaching is given, lessons: School begins at 9 a.m.; 4) all the pupils in a school: The whole school was present at the football match. LSVs 2 and 3 express metonymic transferences based on temporal relations, LSV4 – those based on spatial relations.

To regular patterns of metonymic transferences also refer instrumental relations: the lexeme tongue ‘the organ of speech’ developed the meaning ‘language’: e.g. ‘mother tongue’, because tongue is an instrument which produces speech; the relations between the material and the thing made of this material: silver, bronze, e.g. ‘table silver: spoons, forks, teapots, dishes’; ‘the quality – the subject of this quality’: beauty - 1) combination of qualities that give pleasure to the senses; 2) person, thing, feature that is beautiful: Isn’t she a beauty!; talent - 1) special, aptitude, faculty, gift; 2) persons of talent; ‘action – the agent of the action’: support as a noun: 1) supporting or being supported; 2) sb. or sth. that supports; and some other patterns.

A variety of metonymy is synechdoche, that is the transference of meaning from part to whole, e.g. the case when the nouns denoting the parts of human body come to denote human beings, as the word hand meaning ‘a workman’ (Hands wanted) and ‘a sailor’ (All hands on deck!), the word head meaning cattle (a hundred head of cattle) and others.

The diachronic approach to the word meaning makes it possible to point out the results of semantic change. Results of semantic change can be observed in the changes of the denotational meaning of the word and also its connotational component.

Changes in the denotational meaning may result in either restriction or extension of meaning. Restriction or narrowing of meaning is transference of meaning from a wider, more general meaning to a narrower one: the modern verb to starve ‘suffer or die of hunger’ in Old English meant ‘to die’, disease ‘illness’ previously had the meaning ‘discomfort of any kind’, Restriction of meaning can be also illustrated by the example deer (Old English deor) which previously denoted ‘any animal’ and now it denotes ‘(kind of) graceful, quick-running animal, the male of which has horns’. This is also the case with the word fowl which in Old English denoted ‘any bird’ but in Modern English denotes ‘a domestic hen or rooster’. The word meat, which is today limited to ‘flesh food’ originally meant food in general, as is indicated in the archaic phrase meat and drink ‘food and drink’.

If the word with the new meaning comes to be used in the specialized vocabulary, it is usual to speak of specialization of meaning. For instance we can observe restriction and specialization in the verb to glide which had the meaning ‘to move gently and smoothly’ and has now acquired a restricted and specialized meaning ‘to fly with no engine’.

Changes in the denotational meaning may also result in the application of the word to a wider variety of referents. This is described as extension of meaning and may be illustrated by the word target which originally meant ‘a small round shield’ but now means ‘anything that is fired at’ and also ‘any result aimed at’. The word to help previously meant ‘to treat, to cure’, it has undergone extension of meaning, at present it means ‘do sth. for the benefit of’. If the word with the extended meaning passes from the specialized vocabulary into common use, we describe the result of the semantic change as the generalization of meaning. “Numerous examples of this process have occurred in the religious field, where office, doctrine, novice and many other terms have taken on a more general, secular range of meanings” (Crystal, p.138). Here also belong such examples as the word camp previously belonging to military terms which at present denotes ‘place where people live in tents or huts for a time’.

To semantic change based on extension also refers desemantization [Гак 1977: 32 - 34], that is weakening of the lexical meaning of the word and its grammaticalization. Many verbs of motion lost their meaning ‘manner of moving’ in such examples as to run a risk, to fall into disuse, to fly into a temper, to come to a conclusion. In word combinations like to keep alive, to grow angry, etc. the first components keep, grow have undergone desemantization.

Changes in the denotational component of meaning can be accompanied by changes in the connotational component of meaning which include: a) pejorative development or the acquisition by the word of some derogatory emotive charge, e.g. the word silly originally denoted ‘happy, blessed’ and then gradually it acquired a derogatory meaning ‘foolish, weak-minded’; Modern English villain ‘wicked man’ in Middle English neutrally described a serf; b) ameliorative development or the improvement of the connotational component of meaning, e.g. minister which in one of its meanings originally denoted ‘a servant, an attendant’, but now - ‘a civil servant of higher rank, a person administering a department of state’; angel initially having the meaning ‘a messenger’ developed positive connotational semes ‘lovely, innocent, kind, thoughtful’.

Sure enough, not every word changed its meaning in the course of history of the language. But the diachronic analysis of various types of semantic changes proves that the lexical meaning is one of the most dynamic, changeable elements of the language system, its flexibility is conditioned by the necessity to adequately reflect the constantly changing world.

Synonymy

Lexical units may be classified by the criterion of semantic similarity and semantic contrasts. Such lexemes are either synonyms or antonyms. Synonyms (Greek ‘same’ + ‘name’) are traditionally defined as words similar or equivalent (identical) in meanings. This definition is open to criticism and requires clarification. Synonymy, as D.N. Shmelyov puts it, begins with total identity of word meanings of lexemes relating to one and the same object, and passes through various gradations of semantic affinity to expressing differences in lexical meanings, so that it is difficult to decide whether the words similar in meanings are synonyms or not.

Investigating the problems of synonymy Yu.D.Apresyan considers that the objective difficulties in analysing synonyms stem from the fact that the existing criteria are not sufficient to distinguish synonyms [Апресян 1957: 85].

Linguists point out two main criteria of synonymy: 1) equivalence or similarity of meaning (e.g. pleasure, delight, joy, enjoyment, merriment, hilarity, mirth); 2) interchangeability in a number of contexts, e.g. I’m thankful (grateful) to you. It is a hard (difficult) problem.

However, these criteria are not reliable enough for distinguishing synonyms. First of all it is not clear what degree of similarity is sufficient to determine synonymy. Secondly, one should distinguish both identity and similarity of referents and meanings. One and the same referent might be identified by words which are not synonyms (e.g. оne and the same person can be named mother, wife, daughter, doctor, etc).

It should be noted concerning the criterion of interchangeability that there is little number of lexemes interchangeable in all the contexts. Words broad and wide are very close in meaning, but they cannot substitute each other in a number of contexts, e.g. in the contexts broad daylight, broad accent the substitution of broad by wide is impossible. It is difficult to say how many interchangeable contexts are enough to speak of synonymy.

L.M. Vasilyev writes that synonyms are identified according to their lexical meaning and all their denotational grammatical meanings excluding syntactical meanings; synonyms might differ in other components of their content: conceptual, expressive, stylistic [Васильев 1967].

D.N.Shmelyov gives the following definition of synonyms: “Synonyms may be defined as words belonging to the same part of speech, their meanings have identical components, and differing components of their meanings steadily neutralize in certain positions, i.e. synonyms are words which differ only in such components which are insignificant in certain contexts of their usage” [Шмелев 1977: 196].

N.Webster’ definition is close to the previous one: “in the narrowest sense a synonym may be defined as a word that affirms exactly the meaning of a word with which it is synonymous... Words are considered to be synonyms if in one or more of their senses they are interchangeable without significant alteration of denotation but not necessarily without shifts in peripheral aspects of meaning (as connotations and implications)” [Webster, 1973].

It is erroneous to speak of synonymy of words or lexemes as such, as this part of the definition cannot be applied to polysemantic words. Each meaning (LSV) of a polysemantic word has its own synonymic set, for example, LSV1 of the word party is synonymous with words gathering, social, fun: ‘Are you coming to our party?’; LSV 2 is synonymous with group, company, crowd: ‘A party of tourists saw the sights of London’; LSV 3 is synonymous with block, faction, body, organization: You don’t have to join a political party to vote in an election.

Secondly, if we take into account that lexical meaning falls into denotational and connotational components, it follows that we cannot speak of similarity or equivalence of these two components of meanings. It is only the denotational component may be described as identical or similar. If we analyse words that are considered synonyms, e.g. to leave (neutral) and to desert (formal or poetic) or insane (formal) and loony (informal), etc., we find that the connotational component or, to be more exact, the stylistic reference of these words is entirely different and it is only the similarity of the denotational meaning that makes them synonymous. Taking into account the above-mentioned considerations the compilers of the book “A Course in Modern English Lexicology” R.S.Ginzburg and others formulate the definition of synonyms as follows: “synonyms are words different in sound form but similar in their denotational meaning or meanings and interchangeable at least in some contexts [p.58].”

Differentiation of synonyms may be observed in different semantic components - denotational and connotational. Linguists (W.E.Collinson, D.Crystal, Yu.D.Apresyan) point out differences in the denotational component, e.g. one word has a more general meaning than another: to refuse, to reject; differences in the connotational component, e.g. one word is more emotional than another: youth and youngster are both synonyms but youths are less pleasant than youngsters, or one word is more intense than another, e.g. to repudiate vs. to reject, one word contains evaluative connotation: stringy, niggard (negative – ‘mean, spending, using or giving unwillingly; miserly’) while the other is neutral: economical, thrifty. Differences in connotational meaning also include stylistic differences: one word is formal, e.g. parent while another is neutral father or informal dad; there may be a dialect difference: butcher and flesher (Scots) Synonyms differ in collocation: rancid and rotten are synonyms, but the former is used only of butter or bacon while the latter collocates with a great number of nouns, and frequency of occurrence: turn down is more frequently used than refuse.

It should be noted that the difference in denotational meaning cannot exceed certain limits. There must be a certain common or integral component of denotational meaning in a synonymic set. Componential analysis of word meaning enables linguists to distinguish integral and differential components of synonymous words. Differential components show what synonyms differ in, if compared with one another. For instance, synonyms: to leave, to abandon, to desert, to forsake have an integral component ‘to go away’. The verb to abandon is marked by a differential component ‘not intending to return’, to desert (informal or poetic) means ‘leaving without help or support, especially in a wrong or cruel way’, to forsake presupposes ‘irrevocable breaking away from some place, people, habits, etc., severing all emotional and intellectual contacts’. There is a great variety of differential components. They denote various properties, qualities of nominated objects; they express positive and negative evaluation.

Academician V.V.Vinogradov worked out the follow classification of synonyms which is based on differences between synonyms:

1) ideographic synonyms which differ to some extent in the denotational meaning and collocation, e.g. both to understand and to realize refer to the same notion but the former reflects a more concrete situation: to understand sb’s words but to realize one’s error. Ideographic synonyms belong to one and the same, usually neutral stylistic layer.

2) stylistic synonyms - words similar or identical in meaning but referring to different stylistic layers, e.g. to expire (formal) - to die (neutral) - to kick the bucket (informal, slang).

3) absolute (complete) synonyms are identical in meaning and interchangeable in all the contexts. T.I.Arbekova gives the following examples of perfect synonyms: car - automobile, jail - gaol - prison, to begin - to start, to finish - to end [Арбекова 1977: 22]. There is much controversy on the issue of existence of absolute synonyms. The above and other examples seem to be complete synonyms only at a first superficial glance. A more profound analysis proves that such examples differ in certain connotations and collocability. It is assumed that close to absolute synonyms are terms, e.g. fricative and spirants as terms denoting one and the same type of consonants in phonology. However this understanding is also open to criticism [Arnold 1973].

This classification was subject to alterations and additions. Thus, V.A.Zvegintsev considers that there are no non-stylistic synonyms, but there are synonyms stylistically homogeneous (ideographic) and stylistically heterogeneous (stylistic). According to this point of view ideographic synonyms are pairs like excellent - splendid and stunning - topping (colloq. splendid, ravishing) because they are stylistically homogeneous : the first pair are stylistically neutral synonyms, while the second pair are stylistically coloured; if the above words are put together into one synonymic set, they will be stylistic synonyms.

V.A.Zvegintsev considers that the synonymic set face – countenance – mug – puss – smacker (cf. Rus. лицо – лик – морда – рыло – харя) contains stylistic synonyms while the synonyms in the set mug – puss – smacker (cf. Rus. морда – рыло – харя) are ideographic, because the first set contains stylistically heterogeneous lexemes while the second one includes stylistically homogeneous lexemes [Звегинцев 1968]; it follows that one and the same lexeme can be a stylistic synonym in one set of lexemes (face – mug) and ideographic in another set (mug – puss).

According to the authors of “A Course in Modern English Lexicology” R.S. Ginzburg and others, V.V.Vinogradov’s classification cannot be accepted “as synonymous words always differ in the denotational component irrespective of the identity or difference of stylistic reference” [Ginzburg 1979:56-57 ]. For instance, though the verbs see (neutral) and behold (formal, poetic) are usually treated as stylistic synonyms, there could be also observed a marked difference in their denotational meanings. The verb behold suggests only ‘looking at that which is seen’. The verb see is much wider in meaning.

Difference of the connotational semantic component is invariably accompanied by some difference of the denotational meaning of synonyms. Hence, it would be more consistent to subdivide synonymous words into purely ideographic (denotational) and ideographic-stylistic synonyms.

Synonyms are also subdivided into traditional or language synonyms and contextual or speech synonyms. Some words which are not traditionally considered synonyms acquire similarity of meanings in certain contexts due to metaphoric or metonymic transferences. In the sentence ‘She was a chatterer, a magpie’ the italicized words are not traditional synonyms but the word magpie in this context becomes a synonym to the word chatterer through a metaphoric transference: a magpie-(fig) person who chatters very much. Also in the sentence It was so easy, so simple, so foolproof words easy, simple are traditional language synonyms but foolproof (tech. ‘so simple that it does not require special technical skills or knowledge’) is their contextual synonym.

There is a special type of synonyms - euphemisms (Greek ‘sound well’). They come into being for reasons of etiquette with the purpose of substitution of vulgar, unpleasant, coarse words by words with milder, more polite connotations. For instance, among synonyms drunk, merry, jolly, intoxicated the last three words are euphemisms as they are less offensive than the first one. Euphemisms in various languages are used to denote such notions as death, madness, some physiological processes, diseases, crimes, etc.

Examples of euphemistic synonyms to the verb die are: breathe one’s last, be no more, be gathered to one’s fathers, deep six, give up the ghost, get one’s ticket punched, go belly up, go down the tube, go home in a box, go the way of all flesh, go to one’s last account, go to one’s resting place, go to one’s long home, go north, go west, go to the wall, head for the hearse, head for the last roundup, join the (silent) majority, kick off, kick the bucket, meet one’s maker, meet Mr. Jordan, pay the debt of nature, pass beyond the veil, quit the scene, shuffle off this mortal coil, take the ferry, take the last count, turn up one’s toes; euphemistic synonyms to the word mad: insane, mentally unstable, unbalanced, unhinged, not (quite) right, not all there, off one’s mind (head, hinges, nut, rocker, track, trolley), wrong(off) in the upper storey, having bats in one’s belfry, cracked, cracked-up crackpot, crazy as a bedbug, cuckoo, cutting out paper dolls, nobody home, lights on but nobody home, nutty, just plain nuts, nutty as a fruitcake, out of one’s mind (brain, skull, gourd, tree), loony, head (mental) case, mental defective, gone ape, minus (missing) some buttons, one sandwich short of picnic, belt doesn’t go through all the loops, section 8, etc; euphemisms synonymous to lavatory: powder room, washroom, restroom, retiring room, (public) comfort station, ladies’ (room), gentlemen’s (room), water-closet, w.c., public conveniences, etc.;, euphemistic synonyms to pregnant: in an interesting condition, in a delicate condition, in the family way, with a baby coming, (big) with child. Looking through the above list of examples one can’t fail to notice that euphemisms include items belonging to formal, neutral, informal registers, even some jocular examples.

Оne of the sources of euphemisms are religious taboos, i.e. as it is forbidden to pronounce God’s name, the word God was substituted by a phonetically similar one goodness: for goodness sake! Goodness gracious! Goodness knows! To religious euphemisms also belong: Jove! Good Lord! By Gum! Тhere is also a taboo concerning the usage of the word devil instead of which deuce, fiend, hellion, the Dickens, Old Nick ( Bendy, Blazes, Clootie, Dad, Harry, Horny, Ned, Poker, Scratch, Gentleman, Gooseberry) are used.

The so-called political correctness “p.c.” has become the source of euphemisms in recent years in the U.S.A. and Canada. It is considered politically incorrect to use the word poor instead of which socially underprivileged is used. One should not use words Negroes or blacks but Afro-Americans or Afro-Canadians, not Red Indians but native Americans. Instead of invalids one should say special needs people, pensioners turned into senior citizens, etc.

Synonyms constitute synonymic sets, which include a certain number of synonymous lexemes with a dominant word. A synonymic dominant is a word which represents the integral (invariant) meaning, i.e. the component of meaning common to all the lexemes of a particular synonymic set. Such words are usually stylistically neutral; they have high frequency of occurrence and mostly belong to native English words. The presentation of a synonymic set usually starts with a synonymic dominant: hate, loathe, detest, despise, abominate, abhor. While defining the word’s meaning we usually compare it with the synonymic dominant and only then with other synonyms, e.g. detest – hate strongly (ALD).

The English language is very rich in synonyms. It can be partially explained by intensive borrowing of words from many languages: French, Latin, Greek and others. For instance in the synonymic set with the dominant hate only two lexemes hate and loathe are native English words, others are borrowings from Latin and French. Due to borrowings from these languages there appeared certain synonymic patterns. For instance, a double-scale pattern, where one of the synonyms is a native English word, and another is a Latin borrowing: motherly-maternal, fatherly - paternal, brotherly - fraternal, heavenly - celestial, world -universe, etc.; a triple-scale pattern, where one word is native English, the second one is a French borrowing and the third is borrowed from Latin or Greek: begin - commence - initiate, end - finish - conclude, ask - question - interrogate, etc. In such patterns the first word is stylistically neutral and has a high frequency of usage while others are more formal.

Antonymy

The traditional definition of antonyms as lexemes opposite in meaning sounds straightforward and needs clarification. To antonyms belong such pairs of lexemes as love / hate, early /late, unknown / known, etc. The word ‘opposite’ presupposes quite a variety of semantic contrasts: polarity, exclusion, negation of one concept by another, etc. Cf.: kind/cruel where the opposition expresses contradictory notions and kind/unkind where the opposition expresses negation, i.e. unkind means the same as not kind. Hence, antonyms are lexemes characterized by various kinds of contrasts in their denotational meaning. Antonymy refers to very important semantic relations which form a simple type of structure – contrastive multitude [Харитончик 1992: 105].

Different kinds of contrast make it possible to present a semantic classification of antonyms and point out the following types of antonyms:

1. Contradictory antonyms. Here belong such opposites as single/married, first/last, dead/alive, true / false, perfect / imperfect, etc. To use one lexeme of the pair is to contradict the other: to be alive is not to be dead; to be single is not to be married; to use not before one of them is to make it semantically equivalent to the other. The affirmation of one lexeme of the pair implies the negation of the other. When we state that John is single we imply that John is not married. D.Crystal calls such antonyms complementary [Crystal 1995:165]. The items complement each other in their meanings.

2. Contraries, which are also called gradable antonyms [Crystal 1995:165]. These are opposites, such as large/small, happy/sad, wet/dry, cold/hot, young/old, etc. These are items (adjectives) capable of comparison; they do not refer to absolute qualities. We can say that something is very wet or quite dry, or wetter or drier than something else. It is as if there is a scale of wetness/dryness, with wet at one end and dry at the other. Such antonyms presuppose a certain starting point or norm in regard to which a certain degree of quality is ascertained. Adjectives like big/small, old/young, allow different interpretation depending on what object is meant. Compare for instance a small elephant and a big mouse. Each object has its norm of size: the smallest elephant is bigger than the biggest mouse. The negation of a certain quality in case of contraries does not imply the opposite quality: ‘our town is not big’ does not mean ‘our town is small’.

Contraries unlike contradictories admit possibilities between them. This is observed in pairs like cold/hot where extreme opposite qualities are expressed. Intermediate members make up pairs cold/warm, hot/cool, warm/cool. Contraries may be opposed to each other by the absence or presence of one of the components of meaning like sex or age: man / woman, man / boy, boy / girl.

3. Incompatibles. Semantic relations of incompatibility exist among antonyms with the common component of meaning and may be described as relation of exclusion but not of contradiction. A set оf words with the common component ‘part of the day’: morning, evening, day, night, afternoon may constitute antonymous pairs based on exclusion: morning/evening, day/night, morning/night, etc. To say morning is to say not afternoon, not evening, not night. The negation of this set does not imply semantic equivalence with the other but excludes the possibility of the other words of this set. Relations of incompatibility are also observed between colour terms. Thus black/white exclude red, green, blue, etc.

4. Conversives or converse terms are antonyms denoting one and the same referent viewed from different points of view. This type of oppositeness, where one item presupposes the other, is called converseness. Here belong verbs buy/sell, give/receive, cause/suffer, win/lose; nouns: teacher/student, doctor/patient, husband/wife, parent/child. These antonyms are mutually dependent on each other. There cannot be a wife without a husband. We cannot buy something without something being sold. Close to conversives are antonyms denoting reverse actions: tie / untie, wind / unwind.

5.Vectorial are antonyms such as over/under, inside/outside, North/South, East/West which denote oppositeness of directions referring to spatial relations, actions. Here belong verbs like come/leave, arrive/depart and also those denoting relations of cause and effect: learn / know, know / forget.

It is obvious that not every lexeme has an antonym. A vast majority of lexemes in the language have no opposites at all. It does not make sense to ask ‘What is the opposite of rainbow? Or of chemistry? Or of sandwich?’ Most antonyms are adjectives which is only natural because qualitative characteristics are easily compared: old – new, strong – weak, easy – difficult, high – low, etc. Verbs take the second place, then come nouns and adverbs.

The other point to note is that we ought to differentiate between oppositeness of concepts and meanings. For instance, big and large are very similar in meaning, as are little and small, but the antonym of little is big, and of large is small. Large is not the antonym of little, even though they are conceptually opposed [Crystal 1995:165].

Antonyms are also differentiated as to their structure. The majority of antonyms are the so-called absolute antonyms which have different stems: love/hate, early/late, clever/stupid, etc. Others formed by adding derivational affixes to the stem are derivational (affixal) antonyms. The affixes in them serve to deny the quality stated in the stem: kind/unkind, moral/amoral, useful/useless.

One should bear in mind that in case of polysemantic antonyms as well as synonyms we cannot speak of antonymy of a lexeme as a whole, as different LSVs have different antonyms: thin 1/thick, (a thin/thick slice of bread), thin 2/fat (a thin/fat man).

Homonymy

Words identical in their sound form and/or graphic form (spelling) but different in meaning are traditionally called homonyms, (Gk. homos ‘similar’ and onoma ‘name’). Cf.: bank1 ‘land along each side of a river or canal’ and bank 2 ‘establishment for keeping money and valuables’, write ‘make letters or other symbols on a surface’ and right ‘just, morally good’. Homonymy exists in many languages but Mоdern English is exceptionally rich in homonyms. It is presumed that languages where short words prevail have more homonyms than those with longer words. O.Jespersen calculated that there are approximately four times as many monosyllabic as polysyllabic homonyms. It might be inferred that the abundance of homonyms in Modern English is accounted for by the monosyllabic structure of English words.

The similarity of form in majority of cases is occasional. Homonyms may hinder understanding the sense of the utterance. It is the lexical context that discloses meanings of homonymous words. In the following example several homonyms are used: I could not bear the sight of the poor bear in the bare forest near the construction site ‘Я не мог вынести вида бедного медведя в оголенном лесу возле строительной площадки’ (the еxample is borrowed from [Харитончик, p.72]). Homоnyms are: bear 1 ‘endure, tolerate’, bear 2 ‘large, heavy animal with thick fur’, bare ‘without clothing, covering, protection, decoration’, sight 1 ‘sth. seen’, site 2 ‘place where a building is or going to be’. However, the cоntеxt does not always help determine the word meaning. Тhe example light blue summer dress can be translated either as ‘легкое голубое летнее платье’ or ‘светло-голубое летнее платье’ because of homonyms light 1 ‘not heavy’ and light 2 ‘opposite of darkness’.

Homonyms are often used in jokes and puns which are based on play on words. In the example: “Mine is a long and a sad tale!” said the Mouse, turning to Alice, and sighing. “It is a long tail, certainly,” said Alice, looking down with wonder at the Mouse’s tail; but why do you call it sad?”(L.Carrol. Alice in Wonderland) the play on words is based on homonymous nouns: tale ‘story’ and tail ‘movable part of an animal at the rear of its body’. Also: “What do you do with the fruit? - “We eat what we can, and what we can’t we can”, the pun is based on homonymous verbs can1 ‘be able to’ and can 2 ‘preserve food by putting in a tin-plated airtight container’.

Clаssificаtion of Homonyms

The traditional classification of homonyms is based on the formal criterion of the sound/graphic form. Accordingly homonyms are classified into:

1. Homophones – words identical in sound form but different in spelling (graphic form) and meaning. Examples: son :: sun, see :: sea, piece :: peace, knight :: night, write :: right, I :: eye, two :: too :: to.

2. Homographs – words identical in spelling but different in sound form and meaning. Examples: bow, v., n. [bau] ‘bending of head or body’, bow, n. [bou] ‘a weapon for shooting arrows’, lead, v. [li:d] ‘guide’, lead, n. [led] ‘soft, heavy, easily melted metal, Rus. свинец, tear, v. [teə] ‘pull apart by force’, tear, n. [tiə] ‘drop of salty water coming from the eye’, row, n. [rou] ‘line of benches, people, etc., row, n. [rau] ‘noisy quarrel’.

3. Proper homonyms (full, absolute) - words identical in sound and graphic form but different meaning. Besides the above examples bank 1, bank 2 there are a lot of others: ball 1 ‘dancing party’, ball 2 ‘round sphere used in games, pupil 1 ‘child at a school’, pupil 2 ‘hole in the central part of the eye, through which the light passes, seal 1 ‘sea animal’, seal 2, n. ‘design printed on paper by means of a stamp’ seal 3, v. ‘close tightly’, case 1 ‘box, container’, case 2 ‘something that happens’, etc.

By the type of meaning homonyms are classified into lexical, lexico-grammatical and grammatical:

1. Lexical homonyms are words of the same part of speech, differing in their lexical meanings: bank 1:: bank 2, ball 1:: ball 2; piece :: peace, knight :: night, air :: heir and many others.

2. Lexico-grammatical homonyms differ in lexical and part-of-speech meanings, i.e. they belong to different parts of speech: sea, n. :: see, v., red, a. :: read, v., mean, a. :: mean, v., paw, n. :: pour, v. etc.

3. Grammatical homonyms are word-forms belonging to the same paradigm, differing in their grammatical meanings. For example, in the paradigm of the noun: brothers, pl. - brother's, sing. possessive case - brothers', pl. possess. or in the verb paradigm: to cut, infinitive - cut, past indefinite - cut, past participle.

А.I.Smirnitsky singled out two big classes of homonyms: I. full and II. partial homonyms [1956]. To full homonyms refer words coinciding in all grammar forms, i.e. having identical paradigms. It implies that full homonyms either belong to the same part of speech as, for instance, pupil1 and pupil 2: pupil - pupil’s - pupils - pupils’, or have no paradigms: too :: too :: to.

Partial homonyms fall into three subgroups:

А. Simple lexico-grammatical partial homonyms are words of the same part of speech. Their paradigms have words with identical sound and/or graphic forms (differing in meanings). Examples:

(to) found, v. (Infinitive) :: found , v. (Past Indef., Past Part. of to find);