- •Network Intrusion Detection, Third Edition

- •Table of Contents

- •Copyright

- •About the Authors

- •About the Technical Reviewers

- •Acknowledgments

- •Tell Us What You Think

- •Introduction

- •Chapter 1. IP Concepts

- •Layers

- •Data Flow

- •Packaging (Beyond Paper or Plastic)

- •Bits, Bytes, and Packets

- •Encapsulation Revisited

- •Interpretation of the Layers

- •Addresses

- •Physical Addresses, Media Access Controller Addresses

- •Logical Addresses, IP Addresses

- •Subnet Masks

- •Service Ports

- •IP Protocols

- •Domain Name System

- •Routing: How You Get There from Here

- •Summary

- •Chapter 2. Introduction to TCPdump and TCP

- •TCPdump

- •TCPdump Behavior

- •Filters

- •Binary Collection

- •TCPdump Output

- •Absolute and Relative Sequence Numbers

- •Dumping in Hexadecimal

- •Introduction to TCP

- •Establishing a TCP Connection

- •Server and Client Ports

- •Connection Termination

- •The Graceful Method

- •The Abrupt Method

- •Data Transfer

- •What's the Bottom Line?

- •TCP Gone Awry

- •An ACK Scan

- •A Telnet Scan?

- •TCP Session Hijacking

- •Summary

- •Chapter 3. Fragmentation

- •Theory of Fragmentation

- •All Aboard the Fragment Train

- •The Fragment Dining Car

- •The Fragment Caboose

- •Viewing Fragmentation Using TCPdump

- •Fragmentation and Packet-Filtering Devices

- •The Don't Fragment Flag

- •Malicious Fragmentation

- •TCP Header Fragments

- •Teardrop

- •Summary

- •Chapter 4. ICMP

- •ICMP Theory

- •Why Do You Need ICMP?

- •Where Does ICMP Fit In?

- •Understanding ICMP

- •Summary of ICMP Theory

- •Mapping Techniques

- •Tireless Mapper

- •Efficient Mapper

- •Clever Mapper

- •Cerebral Mapper

- •Summary of Mapping

- •Normal ICMP Activity

- •Host Unreachable

- •Port Unreachable

- •Admin Prohibited

- •Need to Frag

- •Time Exceeded In-Transit

- •Embedded Information in ICMP Error Messages

- •Summary of Normal ICMP

- •Malicious ICMP Activity

- •Smurf Attack

- •Tribe Flood Network

- •WinFreeze

- •Loki

- •Unsolicited ICMP Echo Replies

- •Theory 1: Spoofing

- •Theory 2: TFN

- •Theory 3: Loki

- •Summary of Malicious ICMP Traffic

- •To Block or Not to Block

- •Unrequited ICMP Echo Requests

- •Kiss traceroute Goodbye

- •Silence of the LANs

- •Broken Path MTU Discovery

- •Summary

- •Chapter 5. Stimulus and Response

- •The Expected

- •Request for Comments

- •TCP Stimulus-Response

- •Destination Host Listens on Requested Port

- •Destination Host Not Listening on Requested Port

- •Destination Host Doesn't Exist

- •Destination Port Blocked

- •Destination Port Blocked, Router Doesn't Respond

- •UDP Stimulus-Response

- •Destination Host Listening on Requested Port

- •Destination Host Not Listening on Requested Port

- •Windows tracert

- •TCPdump of tracert

- •Protocol Benders

- •Active FTP

- •Passive FTP

- •UNIX Traceroute

- •Summary of Expected Behavior and Protocol Benders

- •Abnormal Stimuli

- •Evasion Stimulus, Lack of Response

- •Evil Stimulus, Fatal Response

- •No Stimulus, All Response

- •Unconventional Stimulus, Operating System Identifying Response

- •Bogus "Reserved" TCP Flags

- •Anomalous TCP Flag Combinations

- •No TCP Flags

- •Summary of Abnormal Stimuli

- •Summary

- •Chapter 6. DNS

- •Back to Basics: DNS Theory

- •The Structure of DNS

- •Steppin' Out on the Internet

- •DNS Resolution Process

- •TCPdump Output of Resolution

- •Strange TCPdump Notation

- •Caching: Been There, Done That

- •Reverse Lookups

- •Master and Slave Name Servers

- •Zone Transfers

- •Summary of DNS Theory

- •Using DNS for Reconnaissance

- •The nslookup Command

- •Name That Name Server

- •HINFO: Snooping for Details

- •List Zone Map Information

- •Tainting DNS Responses

- •A Weak Link

- •Cache Poisoning

- •Summary

- •Part II: Traffic Analysis

- •Chapter 7. Packet Dissection Using TCPdump

- •Why Learn to Do Packet Dissection?

- •Sidestep DNS Queries

- •Normal Query

- •Evasive Query

- •Introduction to Packet Dissection Using TCPdump

- •Where Does the IP Stop and the Embedded Protocol Begin?

- •Other Length Fields

- •The IP Datagram Length

- •Increasing the Snaplen

- •Dissecting the Whole Packet

- •Freeware Tools for Packet Dissection

- •Ethereal

- •tcpshow

- •Summary

- •Chapter 8. Examining IP Header Fields

- •Insertion and Evasion Attacks

- •Insertion Attacks

- •Evasion Attacks

- •IP Header Fields

- •IP Version Number

- •Protocol Number

- •The Don't Fragment (DF) Flag

- •The More Fragments (MF) Flag

- •Mapping Using Incomplete Fragments

- •IP Numbers

- •IP Identification Number

- •Time to Live (TTL)

- •Looking at the IP ID and TTL Values Together to Discover Spoofing

- •IP Checksums

- •Summary

- •Chapter 9. Examining Embedded Protocol Header Fields

- •Ports

- •TCP Checksums

- •TCP Sequence Numbers

- •Acknowledgement Numbers

- •TCP Flags

- •TCP Corruption

- •ECN Flag Bits

- •Operating System Fingerprinting

- •Retransmissions

- •Using Retransmissions Against a Hostile Host—LaBrea Tarpit Version 1

- •TCP Window Size

- •LaBrea Version 2

- •Ports

- •UDP Port Scanning

- •UDP Length Field

- •ICMP

- •Type and Code

- •Identification and Sequence Numbers

- •Misuse of ICMP Identification and Sequence Numbers

- •Summary

- •Chapter 10. Real-World Analysis

- •You've Been Hacked!

- •Netbus Scan

- •How Slow Can you Go?

- •RingZero Worm

- •Summary

- •Chapter 11. Mystery Traffic

- •The Event in a Nutshell

- •The Traffic

- •DDoS or Scan

- •Source Hosts

- •Destination Hosts

- •Scanning Rates

- •Fingerprinting Participant Hosts

- •Arriving TTL Values

- •TCP Window Size

- •TCP Options

- •TCP Retries

- •Summary

- •Part III: Filters/Rules for Network Monitoring

- •Chapter 12. Writing TCPdump Filters

- •The Mechanics of Writing TCPdump Filters

- •Bit Masking

- •Preserving and Discarding Individual Bits

- •Creating the Mask

- •Putting It All Together

- •TCPdump IP Filters

- •Detecting Traffic to the Broadcast Addresses

- •Detecting Fragmentation

- •TCPdump UDP Filters

- •TCPdump TCP Filters

- •Filters for Examining TCP Flags

- •Detecting Data on SYN Connections

- •Summary

- •Chapter 13. Introduction to Snort and Snort Rules

- •An Overview of Running Snort

- •Snort Rules

- •Snort Rule Anatomy

- •Rule Header Fields

- •The Action Field

- •The Protocol Field

- •The Source and Destination IP Address Fields

- •The Source and Destination Port Field

- •Direction Indicator

- •Summary

- •Chapter 14. Snort Rules - Part II

- •Format of Snort Options

- •Rule Options

- •Msg Option

- •Logto Option

- •Ttl Option

- •Id Option

- •Dsize Option

- •Sequence Option

- •Acknowledgement Option

- •Itype and Icode Options

- •Flags Option

- •Content Option

- •Offset Option

- •Depth Option

- •Nocase Option

- •Regex Option

- •Session Option

- •Resp Option

- •Tag Option

- •Putting It All Together

- •Summary

- •Part IV: Intrusion Infrastructure

- •Chapter 15. Mitnick Attack

- •Exploiting TCP

- •IP Weaknesses

- •SYN Flooding

- •Covering His Tracks

- •Identifying Trust Relationships

- •Examining Network Traces

- •Setting Up the System Compromise?

- •Detecting the Mitnick Attack

- •Trust Relationship

- •Port Scan

- •Host Scan

- •Connections to Dangerous Ports

- •TCP Wrappers

- •Tripwire

- •Preventing the Mitnick Attack

- •Summary

- •Chapter 16. Architectural Issues

- •Events of Interest

- •Limits to Observation

- •Human Factors Limit Detects

- •Limitations Caused by the Analyst

- •Limitations Caused by the CIRTs

- •Severity

- •Criticality

- •Lethality

- •Countermeasures

- •Calculating Severity

- •Scanning for Trojans

- •Analysis

- •Severity

- •Host Scan Against FTP

- •Analysis

- •Severity

- •Sensor Placement

- •Outside Firewall

- •Sensors Inside Firewall

- •Both Inside and Outside Firewall

- •Analyst Console

- •Faster Console

- •False Positive Management

- •Display Filters

- •Mark as Analyzed

- •Drill Down

- •Correlation

- •Better Reporting

- •Event-Detection Reports

- •Weekly/Monthly Summary Reports

- •Summary

- •Chapter 17. Organizational Issues

- •Organizational Security Model

- •Security Policy

- •Industry Practice for Due Care

- •Security Infrastructure

- •Implementing Priority Countermeasures

- •Periodic Reviews

- •Implementing Incident Handling

- •Defining Risk

- •Risk

- •Accepting the Risk

- •Trojan Version

- •Malicious Connections

- •Mitigating or Reducing the Risk

- •Network Attack

- •Snatch and Run

- •Transferring the Risk

- •Defining the Threat

- •Recognition of Uncertainty

- •Risk Management Is Dollar Driven

- •How Risky Is a Risk?

- •Quantitative Risk Assessment

- •Qualitative Risk Assessments

- •Why They Don't Work

- •Summary

- •Chapter 18. Automated and Manual Response

- •Automated Response

- •Architectural Issues

- •Response at the Internet Connection

- •Internal Firewalls

- •Host-Based Defenses

- •Throttling

- •Drop Connection

- •Shun

- •Proactive Shunning

- •Islanding

- •Reset

- •Honeypot

- •Proxy System

- •Empty System

- •Honeypot Summary

- •Manual Response

- •Containment

- •Freeze the Scene

- •Sample Fax Form

- •On-Site Containment

- •Site Survey

- •System Containment

- •Hot Search

- •Eradication

- •Recovery

- •Lessons Learned

- •Summary

- •Chapter 19. Business Case for Intrusion Detection

- •Part One: Management Issues

- •Bang for the Buck

- •The Expenditure Is Finite

- •Technology Used to Destabilize

- •Network Impacts

- •IDS Behavioral Modification

- •The Policy

- •Part of a Larger Strategy

- •Part Two: Threats and Vulnerabilities

- •Threat Assessment and Analysis

- •Threat Vectors

- •Threat Determination

- •Asset Identification

- •Valuation

- •Vulnerability Analysis

- •Risk Evaluation

- •Part Three: Tradeoffs and Recommended Solution

- •Identify What Is in Place

- •Identify Your Recommendations

- •Identify Options for Countermeasures

- •Cost-Benefit Analysis

- •Follow-On Steps

- •Repeat the Executive Summary

- •Summary

- •Chapter 20. Future Directions

- •Increasing Threat

- •Improved Targeting

- •How the Threat Will Be Manifested

- •Defending Against the Threat

- •Skills Versus Tools

- •Analysts Skill Set

- •Improved Tools

- •Defense in Depth

- •Emerging Techniques

- •Virus Industry Revisited

- •Smart Auditors

- •Summary

- •Part V: Appendixes

- •Appendix A. Exploits and Scans to Apply Exploits

- •False Positives

- •All Response, No Stimulus

- •Scan or Response?

- •SYN Floods

- •Valid SYN Flood

- •False Positive SYN Flood

- •Back Orifice?

- •IMAP Exploits

- •10143 Signature Source Port IMAP

- •111 Signature IMAP

- •Source Port 0, SYN and FIN Set

- •Source Port 65535 and SYN FIN Set

- •DNS Zone Followed by 0, SYN FIN Targeting NFS

- •Scans to Apply Exploits

- •mscan

- •Son of mscan

- •Access Builder?

- •Single Exploit, Portmap

- •rexec

- •Targeting SGI Systems?

- •Discard

- •Weird Web Scans

- •IP-Proto-191

- •Summary

- •Appendix B. Denial of Service

- •Brute-Force Denial-of-Service Traces

- •Smurf

- •Directed Broadcast

- •Echo-Chargen

- •Elegant Kills

- •Teardrop

- •Land Attack

- •We're Doomed

- •nmap

- •Distributed Denial-of-Service Attacks

- •Intro to DDoS

- •DDoS Software

- •Trinoo

- •Stacheldraht

- •Summary

- •Appendix C. Detection of Intelligence Gathering

- •Network and Host Mapping

- •Host Scan Using UDP Echo Requests

- •Netmask-Based Broadcasts

- •Port Scan

- •Scanning for a Particular Port

- •Complex Script, Possible Compromise

- •"Random" Port Scan

- •Database Correlation Report

- •SNMP/ICMP

- •FTP Bounce

- •NetBIOS-Specific Traces

- •A Visit from a Web Server

- •Null Session

- •Stealth Attacks

- •Explicit Stealth Mapping Techniques

- •FIN Scan

- •Inverse Mapping

- •Answers to Domain Queries

- •Answers to Domain Queries, Part 2

- •Fragments, Just Fragments

- •Measuring Response Time

- •Echo Requests

- •Actual DNS Queries

- •Probe on UDP Port 33434

- •3DNS to TCP Port 53

- •Worms as Information Gatherers

- •Pretty Park Worm

- •RingZero

- •Summary

The Traffic

The following output represents a handful of TCPdump records to provide the general "flavor" of the activity. The source and destination hosts are bold. These are the first ten records associated with the activity on June 29; there are four different source hosts involved in scanning ten different destination hosts.

The timestamps associated with the records should be regarded with caution. The sensor that captured these records is running Redhat Linux 7.1 with a packet-capturing mechanism known as turbopacket compiled into the kernel. It is supposed to contain a method for more efficient buffering, but it also appears that the timestamp precision has been lost. Timestamps should have microsecond fidelity, but these timestamps appear to have 10-ms resolution:

12:16:31.150575 ool-18bd69bb.dyn.optonline.net.4333 > 192.168.112.44.27374: S 542724472:542724472(0) win 16384 <mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK> (DF) (ttl 117, id

13444)

12:16:31.160575 ool-18bd69bb.dyn.optonline.net.4334 > 192.168.112.45.27374: S 542768141:542768141(0) win 16384 <mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK> (DF) (ttl 117, id

13445)

12:16:31.170575 24.3.50.252.1757 > 192.168.19.178.27374: S 681372183:681372183(0) win 16384 <mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK> (DF) (ttl 117,id

54912)

12:16:31.170575 24-240-136-48.hsacorp.net.4939 >192.168.11.19.27374: S 3019773591:3019773591(0) win 16384 <mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK> (DF) (ttl 117,

id 39621)

12:16:31.170575 ool-18bd69bb.dyn.optonline.net.4335 > 192.168.112.46.27374: S 542804226:542804226(0) win 16384 <mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK> (DF) (ttl 117, id

13446)

12:16:31.170575 cc18270-a.essx1.md.home.com.4658 > 192.168.5.88.27374: S 55455482:55455482(0) win 8192 <mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK> (DF) (ttl 117, id

8953)

12:16:31.170575 24.3.50.252.1759 > 192.168.19.180.27374: S 681485650:681485650(0) win 16384 <mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK> (DF) (ttl 117, id

54914)

12:16:31.170575 cc18270-a.essx1.md.home.com.4659 > 192.168.5.89.27374: S 55455483:55455483(0) win 8192 <mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK> (DF) (ttl 117, id

9209)

12:16:31.170575 24.3.50.252.1760 > 192.168.19.181.27374: S 681550782:681550782(0) win 16384 <mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK> (DF) (ttl 117, id

54915)

12:16:31.170575 cc18270-a.essx1.md.home.com.4660 > 192.168.5.90.27374: S 55455484:55455484(0) win 8192 <mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK> (DF) (ttl 117, id 9465)

DDoS or Scan

At first, it was not apparent if this was some kind of attempted DDoS or an actual coordinated scan of some sort. During the examination of the activity, we were fortunate (from the analysis perspective) to receive additional activity on July 2, 2001 at 16:00 that was remarkably similar.

After we received the second scan, we began in earnest to look at individual fields found in the

received packets of both sets of activity to interpret the nature and intent of the activity.

Source Hosts

In the first scan, 132,706 total packets were received and there were 314 unique source hosts involved. Of those hosts, only 17 (approximately 5.4 percent) did not have DNS registered host names. In the second scan, 157,842 total packets were received. There were 295 unique source hosts with only 24 (approximately 8.1 percent) with unresolved host names. This alone is quite telling. Two choices for categorizing the source hosts are that they either do or do not reflect the genuine source host that is sending the traffic. If the source host reflects the actual sender, no subterfuge is used in sending the packet. If the source host is not the actual sender, a spoofed source IP number is placed in the packet.

Typically, when source IP numbers are spoofed, it is a random generation of different IP numbers in the instance of a flood. Other attacks might use a selection of one or more source IP numbers that might be either a decoy or an eventual target of some kind. When the source host reflects the true sender, the intent is more likely than not to be able to receive a response to the sent traffic.

Therefore, it appears that the activity that was seen is using genuine source IP numbers. If this were a flood and the source IPs were spoofed using randomly generated IP numbers, it is statistically unlikely that these IP numbers would resolve to host names 91.9 to 94.6 percent of the time. It would be unusual that IP numbers would be spoofed using a predetermined set of IP numbers that resolved to host names, because this takes a lot of effort for little or no gain. It can be speculated that, because of the sheer number of source hosts involved, they most likely represent zombie hosts that have somehow been exploited and owned. Many of these source networks are associated with cable modem or DSL providers such as @Home and AOL. This corroborates the speculation of zombie hosts because home users are more likely to be unaware of security threats and less protected than most commercial or larger networks with

some kind of perimeter protection.

Destination Hosts

Next, the analysis moved to examination of the destination hosts to provide more evidence of a scan. The scanned network is Class B with the possibility of 65,535 IP numbers to scan. The first scan targeted 32,367 unique destination hosts and the second scan targeted 36,638 unique destination hosts. An initial unsubstantiated reaction to missed subnets was that there was some prior reconnaissance performed to directly target live hosts. After more thorough examination of the destination hosts, it was evident that many of the destination IP numbers that were scanned had no associated live hosts.

The more plausible explanation for the missing destination subnets and destination hosts is that perhaps the zombie or zombies that were assigned the mission of scanning those subnets were somehow not active or responsive during the scan and did not participate. A single missing destination host in an otherwise scanned subnet might be interpreted as a dropped initial packet rather than an omitted destination IP number.

Although one unique source host scanned most destination hosts, multiple source hosts scanned some destination hosts. The scanner appears to have some redundancy of scanned hosts to

ensure a response.

Scanning Rates

Another indication of a scan versus a flood was the scanning rate of the source hosts. Both scans sustained some kind of activity for five or six minutes; however, the ramp-up time was fast, and there was a burst of activity for the first two minutes.

The measure of bandwidth consumption was as follows. Each packet was a SYN packet with TCP options and no payload. Most packets had a length of 48 bytes, a few had more, and a few had 4 bytes less, depending on the number and types of TCP options used. Packets had a standard 20-byte IP header with no IP options. Because the majority of packets had a length of 48 bytes, this was used as the packet length for the computation of bandwidth consumption. Because throughput or bandwidth is measured in bits per second, the packet length was 384 (48 * 8)

bits.

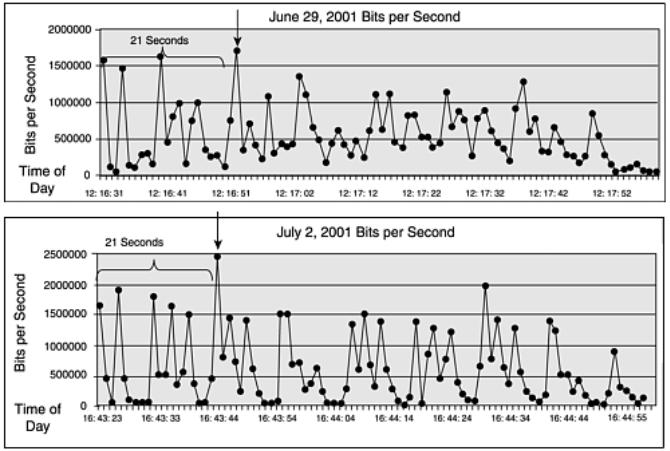

The scan on June 29 reached a maximum rate of 1.7Mbps at peak. The second scan on July 2 reached a maximum rate of 2.4Mbps at peak. This did not adversely affect the monitored site, but a site with a smaller ingress pipe such as a T-1 with 1.554Mbps capacity might have suffered a temporary denial of service as a side effect of the scan. Figure 11.1 shows the bits per

second during peak scan minutes.

Figure 11.1. Bits per second.

Looking at the plots in Figure 11.1 together, it is apparent from the general contours that the scanning rates for both scans were very similar. In fact, both scans reached peak scanning rates at exactly 21 seconds after the scan began. As discovered later, after examining the traffic using different representations, this peak activity indicated some kind of coordination by the "commander" who allocated scanning assignments and rates for the zombies.

Peak rates could have occurred because there were more scanning hosts during that second or because the number of packets sent by hosts increased. Further scrutiny of the data revealed that the peaks and valleys correlated with an increased number of scanning hosts.

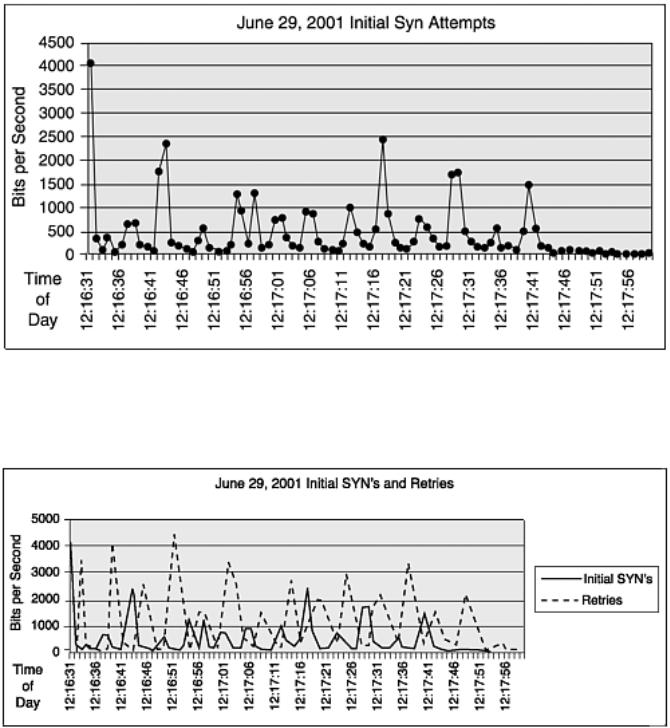

The 21-second peak rate that was observed yet again on a third scan on November 1 was indeed a mystery. However, it was observed that the scanning hosts sent retries of initial SYN connections that received no response. This is typical TCP behavior, and many TCP/IP stacks will attempt 3 retries after the initial SYN, with a formula of waiting 3 seconds before the first retry, doubling the wait time to 6 seconds for the second retry and doubling the wait time yet again to 12 seconds for the third and final retry. Hence, the aggregate time that passes between the initial SYN and the final retry is 21 seconds. And so, when initial SYN attempts only were plotted by time as in Figure 11.2, the 21-second peak disappears.

Figure 11.2. June 29, 2001 initial SYN attempts.

This only partially explains the 21-second peak. If this peak were due strictly to retries alone of the same hosts, similar peak activity should be observed at 3 and 9 seconds as well.

shows two separate types of connection attempts by time for the June 29 scan—the solid line shows initial SYN attempts and the dashed line shows retries of those initial SYN attempts. This more completely explains the 21-second peak.

Figure 11.3. June 29, 2001 initial SYNs and retries.

Peak activity occurs at 12:16:52. As expected, this corresponds to the 3rd retry of the spate of attempted SYN connections sent at 12:16:31. Furthermore, it corresponds to the second retry of the deluge of another set of initial SYN attempts sent 9 seconds before peak activity at 12:16:42. More so, in both scans, it appears, at least at first, that the wave of initial SYN connections comes in 12-second intervals. The overlap of retries from this particular timing pattern is why the 21-second peak activity was witnessed.