Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

396

neuroendocrine liver metastases detected by other imaging and often discovers new sites. Octreotide scintigraphy also detects those tumors potentially responsive to radiolabeled octreotide therapy, but even here caution is necessary—liver, spleen, kidneys, and bladder are routinely visualized, while neuroendocrine tumors (and lymphomas) show variable uptake; therapy using somatostatin analogues may not be appropriate for all tumors accumulating In-111-DTPA-D-Phe-octreotide (In-111- pentetreotide).

Schwannoma

A primary schwannoma of the liver without associated neurofibromatosis is rare. Initially these are solid tumors, but with growth they tend to necrose and invade adjacent structures, including stomach.

Carcinoid

Most carcinoids originate in the gastrointestinal tract, with an occasional primary in some other organ, such as breast; even these metastasize to the liver. Primary liver carcinoids are rare; of interest is that the carcinoid syndrome tends not to develop in these patients. Carcinoid syndrome develops if tumor blood flow drains into the systemic venous circulation. Thus, in general, in a setting of a known primary carcinoid, the presence of carcinoid syndrome usually implies hepatic metastases, although exceptions occur and occasionally carcinoid syndrome is not evident even with widespread liver involvement.

Multiple liver foci are more common than solitary ones. Being metastatic, these carcinoids are malignant, yet specific imaging findings do not aid in differentiating between benign and malignant ones. Precontrast CT identifies carcinoid metastases as hypodense tumors, although small ones tend to be isodense. Central necrosis in larger tumors is hypodense. They enhanced during the arterial phase, with contrast enhancement then decreasing; superficially, they can mimic a hemangioma. A minority of focal carcinoids are best seen precontrast. Some are identified only on one phase.

Ultrasonography shows these tumors to range from hypoto hyperechoic; central necrosis is anechoic. Some tumors are surrounded by a hypoechoic halo.

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

These tumors are hypointense on T1and hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI; they enhance markedly during the arterial phase, less so during portal phase. A peripheral hypointense ring is seen in some of these tumors during delayed imaging, a finding also detected with some other hypervascular metastases.

Digital subtraction angiography identifies neovascularity. Larger tumors are fed by tortuous and elongated arteries. Carcinoids tend to displace and compress adjacent portal veins but not invade.

Most carcinoids contain somatostatin receptors, and octreotide scintigraphy is useful in localizing them. They are amenable to octreotide therapy.

Indium-111 pentetreotide and iodine- 123–vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor imaging should suggest a carcinoid. Indium- 111-pentetreotide SPECT detects more tumors than planar scans or conventional imaging.

The radiopharmaceutical metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG), used in the imaging and therapy of pheochromocytomas and neuroblastomas, has a limited role in imaging metastatic liver carcinoids because other imaging is more sensitive. Iodine-131-MIBG is useful, however, in treating carcinoids.

Interferon therapy has led to a clinical response, but symptoms recur after end of therapy. Embolization has had a limited application.

Gastrinoma

A rare primary liver gastrinoma has been reported.

T2-weighted sequences reveal a wellmarginated, homogeneous, hyperintense tumor. Arterial phase MR sequences show larger tumors to have either homogeneous or peripheral enhancement, while smaller ones tend to be homogeneous and mimic hemangiomas. Delayed sequences show faster contrast washout than with most hemangiomas, and these sequences are most useful in differentiating metastatic gastrinomas from hemangiomas.

The intraarterial secretin test consists of sampling venous blood after secretin injection. In patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, the secretin test is positive in only half or so of patients. This detection rate is less than with

397

LIVER

other imaging available. The secretin test is |

Bilateral diffuse hepatic nodules are a |

||||||||

useful when CT and MR are nondiagnostic. |

common finding with hemangioendotheliomas. |

||||||||

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy detects |

Tumor nodules tend to be rather uniform in |

||||||||

more gastrinoma metastases than CT, MRI, or |

size; they are hypointense on T1and hyperin- |

||||||||

angiography. As expected, somatostatin recep- |

tense on T2-weighted images. They enhance |

||||||||

tor scintigraphy does not identify hemangiomas |

postcontrast. |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

and thus aids in this differentiation. |

|

Hemangioendotheliomas |

and |

cavernous |

|||||

Indium-111-pentetreotide SPECT is becom- |

hemangiomas have a similar CT and MRI |

||||||||

ing the imaging procedure of choice for sus- |

appearance. |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

pected gastrinoma. |

|

Some infantile hemangioendotheliomas have |

|||||||

|

|

an early “blush” on Tc-99m–red blood cell |

|||||||

Other Tumors |

|

scintigraphy. |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Insulinomas metastatic to the liver tend to be |

Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma |

||||||||

slow growing. Either curative or |

palliative |

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma is a more |

|||||||

surgery is often considered. Chemotherapy or |

|||||||||

recently described entity |

involving multiple |

||||||||

transcatheter arterial embolization |

prolongs |

||||||||

organs, including skin, liver, spleen, lungs, brain, |

|||||||||

survival. Chemical shift MR occasionally reveals |

|||||||||

and intestine. It is believed to be clinically and |

|||||||||

a rim of steatosis surrounding metastatic insuli- |

|||||||||

histologically |

distinct |

from the more typical |

|||||||

nomas, presumably due to local insulin release |

|||||||||

hemangioma found in infancy. It is an aggres- |

|||||||||

(155). |

|

||||||||

|

sive, locally invasive tumor that does not metas- |

||||||||

Pheochromocytomas originate in a number |

|||||||||

tasize. In spite of the name, this tumor, together |

|||||||||

of organs, but a liver primary is exceedingly |

|||||||||

with spindle cell hemangioendothelioma, is not |

|||||||||

rare. |

|

||||||||

|

associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus |

||||||||

Liver neurofibromas are rare and are associ- |

|||||||||

(human herpesvirus 8); a polymerase test for |

|||||||||

ated with neurofibromatosis type |

1. These |

||||||||

Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus can be used to |

|||||||||

tumors involve intrahepatic nerves |

and thus |

||||||||

distinguish between |

Kaposi’s |

sarcoma and |

|||||||

tend to have a periportal sheath-like distribu- |

|||||||||

other vascular tumors. |

|

|

|

|

|||||

tion. Computed tomography reveals |

a hypo- |

|

|

|

|

||||

The histologic findings combine those found |

|||||||||

dense infiltrating tumor mimicking lymphoma |

|||||||||

in a |

tufted |

angioma, lymphangioma, and |

|||||||

or a mesenchymal tumor. |

|

||||||||

|

Kaposi’s sarcoma. |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

Kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas mani- |

|||||||

|

|

fest |

somewhat later |

in |

life |

than |

infantile |

||

Hemangioendothelioma |

hemangiomas and are often associated with |

|

|

|

anemia, thrombocytopenia, and a coagulopathy |

|

(Kasabach-Merritt syndrome), and occasionally |

|

with lymphangiomatosis. Nevertheless, some of |

|

these tumors have been misdiagnosed as infan- |

|

tile hemangiomas. Some authors suggest that |

|

Kasabach-Merritt syndrome does not occur |

|

with hemangiomas, and if this syndrome is |

|

present a kaposiform hemangioendothelioma |

|

should be considered. Whether the occasional |

|

adult with a large so-called hemangioma and |

|

exhibiting Kasabach-Merritt syndrome actually |

|

has a hemangioendothelioma is conjecture. |

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma

Epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas do metastasize and should be classified as malignant vascular tumors. Most occur in middle-aged

398

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

A B

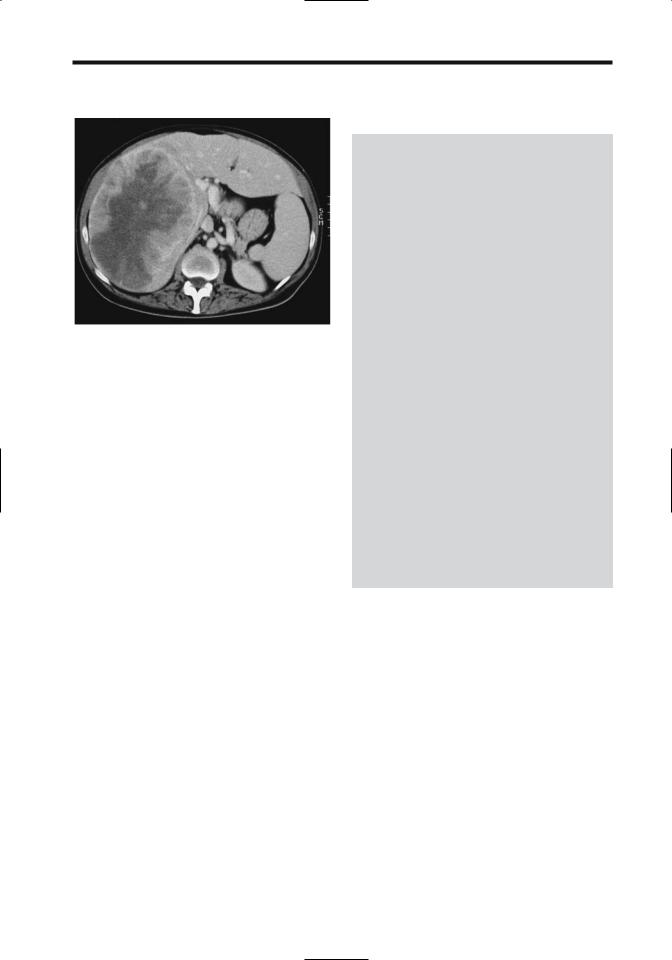

Figure 7.48. Liver hemangioendotheliosis in a 1-year-old girl. She also has skin hemangiomas and has mild congestive heart failure. A: Precontrast CT reveals an extensive blood density infiltrate involving large portions of the liver. B: Contrast-enhanced CT shows a heterogeneous tumor mostly isodense with liver. Of note is the small caliber aorta. (Courtesy of Luann Teschmacher, M.D., University of Rochester.)

women, but children are not spared. The underlying liver is usually normal.

Imaging defines the size and extent of these tumors, but their appearance often suggests a hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver biopsy is needed to establish a diagnosis. Ultrasonography is generally used to follow these lesions.

Varying degrees of mottled calcifications develop eventually.

Computed tomography reveals a hypodense tumors (Figs. 7.48 and 7.49). They tend to be hypervascular in their periphery. Contrast CT shows early peripheral enhancement followed by delayed central enhancement. Central enhancement is absent if sufficient fibrosis or thrombosis evolve. Even with extensive tumors in both lobes, the underlying hepatic vascularity tends to be normal.

These tumors are hypointense on T1and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, although considerable variability exists.

Patients with epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas have undergone successful liver transplantation.

Other Hemangioendotheliomas

Retiform, polymorphous, and composite hemangioendotheliomas and the malignant endovascular papillary angioendothelioma

usually infiltrate locally and have a high rate of local recurrence, and some will metastasize. They should be considered low-grade malignancies.

Figure 7.49. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma in an 18-year- old woman. Contrast-enhanced CT reveals a large heterogeneous, lobulated tumor involving both right and left lobes. Some of the vessels coursing into it are attenuated. She underwent liver transplantation. (Courtesy of Patrick Fultz, M.D., University of Rochester.)

399

LIVER

Figure 7.50. Metastatic hemangiopericytoma. She had surgery years ago for a meningeal hemangiopericytoma. A large right lobe tumor is evident. (Source: Cancer 1999;85(10):2245–2248. Copyright 1999 American Cancer Society. Reprinted by permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Courtesy of Dr. F. Grunenberger, Hôpital de Hautepierre, Strasbourg.)

Hemangiopericytoma

The rare primary liver hemangiopericytoma occurs in both children and adults. Clinically and radiologically these tumors suggest a hemangioma or a hemangioendothelioma. Some express angiogenic factors such as fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.

Occasionally detected is a metastatic hemangiopericytoma (Fig. 7.50). Some of these patients present with hypoglycemia; a history of a hemangiopericytoma resected years ago is not uncommon.

Calcification

Numerous disorders lead to increased liver parenchymal density and most are discussed in their respective sections. Not all increased density is due to calcium deposition. Increased iron stores and thorotrastosis are two such noncalcium conditions.

Whether calcifications are diffuse or focal, linear or curved, dense or barely visible allows one to narrow the differential diagnosis (Table 7.16). The patient’s age, likewise, aids in differentiating diagnoses.

Table 7.16. Conditions associated with liver calcifications

Diffuse parenchymal calcifications

In childhood

Toxoplasmosis

Cytomegalovirus

Rubella

Herpes simplex virus

Neonatal syphilitic hepatitis

Granulomatous hepatitis

Tuberculosis

Histoplasmosis

Schistosomiasis (Schistosoma japonicum)

Pneumocystis carinii (usually in AIDS)

Associated with hemoor peritoneal dialysis

Amyloidosis

Silicosis

Lymphoma

After liver ischemia

Post-transplant hepatic artery thrombosis

Focal calcifications:

Prior pyogenic abscess

Prior amebic abscess

Hydatid cyst

Primary liver tumors

Cavernous hemangioma

Focal nodular hyperplasia

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

Metastatic neoplasm

Mucin-producing adenocarcinoma

Osteogenic or chondrosarcoma

Some neuroendocrine tumors

Aneurysms

Intrahepatic biliary stones

Vascular Disorders

Vascular Congestion

Systemic venous engorgement, such as with congestive heart failure, constrictive pericarditis, or an episode of hypotension, leads to liver congestion, hepatomegaly, and, if severe enough, eventual liver ischemia and central lobular necrosis. Underlying liver damage is often unexpected. Shock has led to acute liver necrosis. Cirrhosis is an end point if congestion is chronic. Associated renal failure is common. These patients present with a marked increase in transaminase levels that tend to normalize rapidly. A coagulopathy with a prolonged prothrombin time is common.

400

Contrast-enhanced CT reveals a mottled pattern throughout the liver and delayed hepatic vein enhancement. Periportal lowattenuation nonenhancing fluid is a manifestation of venous stasis. The inferior vena cava becomes engorged and enlarges.

Enlarged hepatic veins and, at times, an enlarged inferior vena cava are gray-scale US findings of liver vascular congestion. Doppler US shows prominent portal vein pulsatility. In patients with heart failure, duplex Doppler US reveals that those with more severe left ventricular failure have a reduced portal vein pulsatility ratio; in fact, portal vein pulsatility correlates better with worsening cardiac function than vena caval or hepatic vein diameters. In chronic congestive heart failure the hepatic veins lose their triphasic contractility.

Infarction

The liver’s dual blood supply makes major hepatic infarcts rare in the absence of prior surgical or radiologic intervention. Most major infarcts are encountered after liver transplantation. After a pancreaticoduodenectomy, liver infarction is more common in patients undergoing combined portal and superior mesenteric vein resection but not in those without a combined vascular resection. Liver infarcts develop in patients with vasculitides, polycythemia vera, and disseminated intravascular hypercoagulation. Sickle cell disease is associated with liver infarcts, although many of these are not detected with imaging. Blunt trauma is a rare cause of a major liver infarct. Liver infarction is a rare complication of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Focal liver infarcts occur in association with diffuse or focal liver disease, often after obstruction of an intrahepatic branch of the hepatic artery. Occlusion of a portal vein branch does not result in an infarct (except in neonates). Etiology of some biopsyconfirmed focal necrosis can be identified, but in others differentiation among infection, tumor, and ischemia is not possible. Some focal infarcts evolve into focal necrosis and an abscess; others presumably heal with few sequelae.

A typical infarct appears as a wellmarginated, wedge-shaped, peripheral defect; more centrally located infarcts are harder to identify. Within several days of necrosis, con-

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

ventional radiography and CT detect gas bubbles in the liver, a transient finding. With a sufficient insult eventual parenchymal atrophy and scarring ensue. Some patients eventually develop diffuse liver calcifications.

Contrast-enhanced CT of an infarct reveals a hypodense region due to hypoperfusion, generally in the periphery. With hepatic artery obstruction, Doppler US identifies the lack of flow in the porta hepatis, although intrahepatic arterial flow may still exist due to collateral vessels. Occluded feeding arteries are identified in some patients.

Following abdominopelvic surgery not related to the liver, some patients develop wedge-shaped liver defects. These defects range from hypoto hyperdense on precontrast CT. Postcontrast, these defects appear homogeneous and of higher attenuation than the surrounding liver. Of interest is that in some patients CT also detects portal vein branch clots within these defects. Follow-up CT reveals most of these defects diminishing with time, although some can persist. These postoperative defects probably represent a portal venous system thromboembolic phenomenon, and CT contrast enhancement is due to compensatory increase in hepatic arterial flow.

Postcontrast MRI reveals an infarct as a hypointense region.

Veno-Occlusive Disease

Hepatic vein obstruction is secondary to thrombosis or to such etiologies as chemotherapy or toxin ingestion. It is a rare complication of therapeutic liver radiation.

Jamaican herbal tea (Senecio vulgaris) drinkers are at increased risk of hepatic venoocclusive disease. Clinically, these patients have findings similar to Budd-Chiari syndrome but imaging reveals patent major hepatic veins and inferior vena cava. Portal vein blood flow is decreased in this condition.

Budd-Chiari syndrome is discussed in Chapter 17.

Shunts

Arteriovenous

Intrahepatic arteriovenous shunting, if significant enough, leads to hepatic artery

401

LIVER

enlargement and early venous contrast enhancement through the shunt. Early venous enhancement is also seen with some hypervascular neoplasms such as hepatocellular carcinomas. These findings are identified with postcontrast CT and arteriography.

Arterioportal

Small arterioportal venous shunts (not related to neoplasms), identified by hepatic angiography, appear as perfusion defects at CT arterial portography.

Arterial-phase dynamic MRI of small nontumorous arterioportal shunts reveal wedgeshaped, nodular, or irregular-shaped regions of contrast enhancement (156); they are not identified by unenhanced MRI. These nontumor arterioportal shunts are a cause of focal liver arterial MR hyperperfusion in a setting of normal precontrast MRI.

Liver in Idiopathic

Portal Hypertension

Whether idiopathic noncirrhotic, chronic portal hypertension is one condition or a final pathway of several disorders is speculation. Histology reveals dense portal fibrosis, portal venous obliteration, and intralobular fibrosis; the appearance is similar to that found in nodular regenerative hyperplasia.

Some patients with idiopathic portal hypertension develop decreased portal venous peripheral perfusion. These regions enhance during arterial phase dynamic and are hypointense on T1and hyperintense on T2weighted MRI. Technetium-99m-GSA scintigraphy shows decreased accumulation, indicative of dysfunction.

Other Vascular Disorders

In patients with portal vein obstruction (in either the right or left lobe portal veins), immediate CT and MR contrast-enhanced images reveal an initial transient increase in segmental hepatic enhancement distal to the obstruction; this enhancement is secondary to increased hepatic arterial blood flow to the obstructed segment.

Hepatic sinusoidal dilatation, a rare interesting vascular condition, is associated with focal hepatocyte necrosis and intrasinusoidal fibrosis. It occurs in a setting of oral contraceptive use or pregnancy. CT reveals a poorly marginated heterogeneous hypodense region during the portal phase which gradually becomes isodense (157); T2-weighted MR identifies vessels within the lesion, an uncommon finding with a neoplasm. Delayed contrast enhancement separates this condition from peliosis hepatis, which tends to enhance early.

Vasculitides are prone to bleed, usually intrahepatic, less often intrabiliary or intraperitoneally. Some of these bleeds can be treated with transcatheter arterial embolization.

HIV/AIDS

Clinical

It is common to see hepatomegaly and splenomegaly in a setting of HIV infection. In general, low attenuation lesions in the liver should not be ascribed directly to HIV; most are secondary to another infection or a neoplasm.

Liver histology is abnormal in most autopsied HIV patients; steatosis is most common. Steatosis developing in HIV infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy leads to hepatomegaly and is a severe and potentially fatal complication.

Imaging

Ultrasonography findings in HIV-positive patients are less specific than in the general population. In almost half of these patients US shows a diffuse hyperechoic liver, presumably secondary to steatosis.

Some opportunistic liver and splenic infections result in an US snowstorm appearance. Fibrosis or a fibrinous exudate probably accounts for this appearance.

Infection

Bacillary angiomatosis, a liver infection complicating AIDS, is caused by infection with

Bartonella henselae or B. quintana. It mimics Kaposi’s sarcoma. Computed tomography

402

reveals hypodense tumors that enhance postcontrast.

Pneumocystis carinii infection has led to acute hepatic failure due to P. carinii obstructing the hepatic sinuses and capillaries. Calcifications develop in lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and kidneys.

Liver function tests are abnormal but no specific imaging findings are seen with liver toxoplasmosis.

Immunocompromised children tend to develop multiple small liver abscesses, often fungal in origin, rather than a large drainable abscess.

Although disseminated tuberculosis is not uncommon in HIV patients, hepatic tuberculous abscesses are rare. Focal liver involvement is unusual and only an occasional AIDS patient develops liver tuberculomas.

Malignancy

An occasional hepatocellular carcinoma develops in an HIV-infected patient with no evidence of chronic liver disease or viral infection. Primary liver lymphomas also are found in HIV patients. Discrete tumors, rather than diffuse infiltration, predominate. A biopsy should be diagnostic.

Kaposi’s sarcomas tend to infiltrate the portal triads.

Rare hepatic leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas have developed in children with AIDS.

Postoperative Changes

Liver Transplantation

Pretransplant

Clinical

Children

The most common indication for orthotopic liver transplantations among 198 children was biliary atresia (42%), followed by a1-antitrypsin deficiency (8%), Alagille’s syndrome (8%), and fulminant hepatic failure (7%) (158); over half of these children were under 5 years of age. Other indications for a liver transplant in children include cryptogenic cirrhosis, and an occasional child has cystic fibrosis and resultant biliary cirrhosis. A severe organ shortage exists

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

for children. In part, this shortage has been alleviated by using reduction hepatectomy to produce more manageable-sized liver allografts; only the left lobe or even a segment of the lobe is transplanted.

Similar to transplantation of an entire liver, infants with reduced transplants (left lateral segment or split-liver transplant grafts) also undergo a Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy. The vascular and biliary anatomy is different from that seen with whole liver transplantation if only a partial liver transplant is performed.

At times TIPS stabilizes an adult or child with liver failure and life-threatening variceal bleeding sufficiently to permit liver transplantation later.

In one center the 1-year actuarial survival rate in children was 80% (increasing to 88% over the last 5 study years) and for those surviving more than 1 year, the 3-, 5-, and 10-year actuarial survival rates were 95%, 93%, and 93%, respectively (158).

Adults

The most common indications for orthotopic liver transplantation in adults are cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis, and fulminant hepatic failure. End-stage hepatitis B cirrhosis patients were considered to be poor candidates for transplantation due to a high recurrence rate, but more recent medical therapy has led to a more favorable response. Hepatitis C virus infection recurs in most patients posttransplant and appears to be relatively benign, but the longterm sequelae are not known. In select patients transplantation is a viable option for early primary liver cancer. Prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma is greater in a transplant recipient undergoing transplantation for cirrhosis than in the general population, with some of these cancers not detected by pretransplant imaging. Performing both CT arterioportography and DSA pretransplant achieves a sensitivity of about 85% in detecting hepatocellular carcinomas in cirrhotic livers but these tests have a relatively high false positive rate (159). Although pretransplant knowledge of an incidental neoplasm is of obvious importance, one may argue that due to the generally small size of most of these tumors the patient would still be eligible for transplantation.

Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis who have developed a cholangiocarcinoma do

403

LIVER

poorly after liver transplantation; the current trend is to perform liver transplantation earlier in the course of primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, a complication of cirrhosis, is not a contraindication to liver transplantation provided adequate therapy for peritonitis is administered prior to transplantation.

The role of TIPS prior to transplantation is discussed in Chapter 17. The malposition of TIPS stents, however, alters and prolongs liver transplantation by interfering with crossclamping at usual vascular sites.

Living donor transplantation involves right lobectomy or segmentectomy or left lobectomy or segmentectomy. Regeneration is a rapid process, with a transplant doubling in size within three or so weeks. Postoperative complications do occur in liver donors. Complications occur more often in right lobe than left lobe donors (160); many of these complications are amenable to interventional management, such as percutaneous drainage, bile duct dilation, arterial embolization or stent placement and resolve.

Imaging

Preoperative recipient assessment is designed to detect any anatomic variance such as portal vein patency and its major branches, and the caliber, location, and patency of the hepatic artery, hepatic veins, and inferior vena cava. Probably the most useful single imaging modality for preoperative evaluation of a potential liver transplant candidate is contrast-enhanced CT, especially multislice. This study calculates liver volume, evaluates adjacent structures, and defines underlying vascular anatomy.

Multidetector multiphase CT provide comprehensive parenchymal, vascular, and volumetric evaluation of potential living adult donors for right lobe liver transplantation. Agreement is found in donors between virtual CT right lobe volumes and graft weights obtained at surgery.

Arterial phase and portal venous phase CT with 3D volume rendering techniques can define major vessel origins, portal vein thromboses and cavernous transformation, collateral vessels, and detect unsuspected liver tumors. Such vascular information appears similar to or even superior to that obtained with DSA.

At times resection of only the left lobe or left lateral segment is performed in living donors for related transplantation, and any anatomic venous variation needs to be determined. Often US is sufficient for this task. It can identify whether the hepatic veins form a common trunk or drain separately into the inferior vena cava.

Preoperative right lobe living donor evaluation is also feasible with comprehensive abdominal T1and T2-weighted MRI, MR cholangiography, and MR angiography; Preoperative MR evaluation in right hepatic lobe donors provides right lobe volume data similar to surgically obtained volumes, outlines intrahepatic bile duct anatomy in more patients than intraoperative cholangiography, and depicts portal veins more completely than DSA (161). Preoperative MRI findings can exclude donors, although a right hepatectomy was aborted at laparotomy in several patients because of intraoperative cholangiography findings at variance to preoperative imaging (162). A specific role for MRI is yet to be established in living donors. Of interest is a study of iodipamide enhanced multidetector CT cholangiography, showing significantly better donor biliary tract visualization than with conventional MR or mangafodipir enhanced excretory MR cholangiography (163).

Technetium-99m-GSA, binding to asialoglycoprotein liver receptors, is useful in evaluating hepatic functional reserve both prior to and after transplantation.

Is selective angiography necessary in children with end-stage liver disease who present for orthotopic liver transplantation? Such selective study does provide detailed portal vein and hepatic artery anatomy but at some risk to these children.

Intraoperative

In addition to preand posttransplantation evaluation, intraoperative vascular US appears useful if vascular compromise is suspected. Intraoperative US aids in establishing a liver transection line for an extended lateral segmentectomy by identifying the left medial vein.

A typical liver transplantation requires five anastomoses: four vascular ones involving the hepatic artery, portal vein, and supraand infrahepatic inferior vena cava, and an end-to-end biliary anastomosis. A T-tube stent was often

404

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

left in place across the biliary anastomosis, although a number of surgeons have abandoned T-tube drainage to prevent bile leakage from the site. With the latter, biliary complications must be approached via ERCP. If a biliary anastomosis is not feasible, a choledochojejunostomy is created. A cholecystectomy is performed.

Posttransplant

The consequences of prolonged immunosuppressive therapy are still not completely understood.

Imaging

Computed tomography detection of focal subcapsular hepatic necrosis at some point in time is common after liver transplantation. In general, this finding is of little clinical prognostic significance, although it is associated with acute rejection.

A suprahepatic circumcaval calcification is occasionally detected by CT after transplantation. It is probably of little consequence.

Although IV Levovist in liver transplant patients results in significantly better color Doppler US arterial signals, little or no improvement is evident for the main portal vein and hepatic vein.

Magnetic resonance imaging defines hepatic venous anatomy and determines the liver volume and portal venous blood flow.

Complications

Rejection

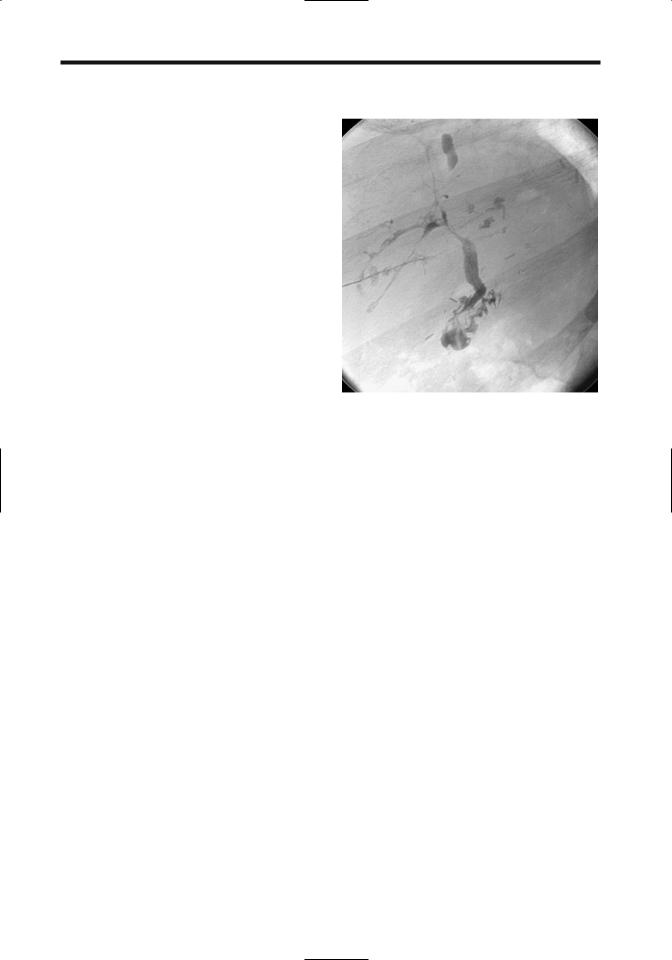

Rejection is usually first detected roughly a week after transplantation. No specific imaging finding suggests liver rejection. During acute rejection the liver becomes edematous and intrahepatic bile ducts are compressed, resulting in incomplete filling during cholangiography (Fig. 7.51). Chronic rejection manifests by multiple bile duct strictures and a gradual and progressive reduction in number of interlobular bile ducts. In a setting of suspected rejection, imaging is used primarily to exclude biliary, vascular and other causes that clinically mimic rejection.

In some patients CT and MRI show a perivascular collar around central portal vein branches, probably secondary to impaired lymphatic drainage and resultant lymph edema.

Figure 7.51. Presumed rejection of second liver in patient with autoimmune hepatitis. Numerous narrowed and dilated biliary segments are scattered throughout the liver. Ischemia can have a similar appearance. (Courtesy of David Waldman, M.D., University of Rochester.)

Doppler US changes in vessel diameter and blood flow data do not correlate consistently with acute rejection or with liver biopsy findings.

Biliary Complications

Posttransplant biliary complications encountered during the acute period consist of leakage and obstruction. Bile duct necrosis is uncommon. Strictures or stones develop on a more chronic basis.

Cholangiography, via an inserted catheter, endoscopic approach,or percutaneously,studies the suspected biliary complications (Fig. 7.52). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is evolving into a viable alternative by identifying first-order intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts in over 90% of recipients. Enhancement with mangafodipir trisodium outperform conventional MR cholangiography in detecting and excluding biliary abnormalities (164).

In children, a diagnostic cholangiogram can be obtained in over 90% of attempted percutaneous transhepatic cholangiograms and a drainage catheter successfully inserted in most (165); of note is that a diagnostic cholan-

405

LIVER

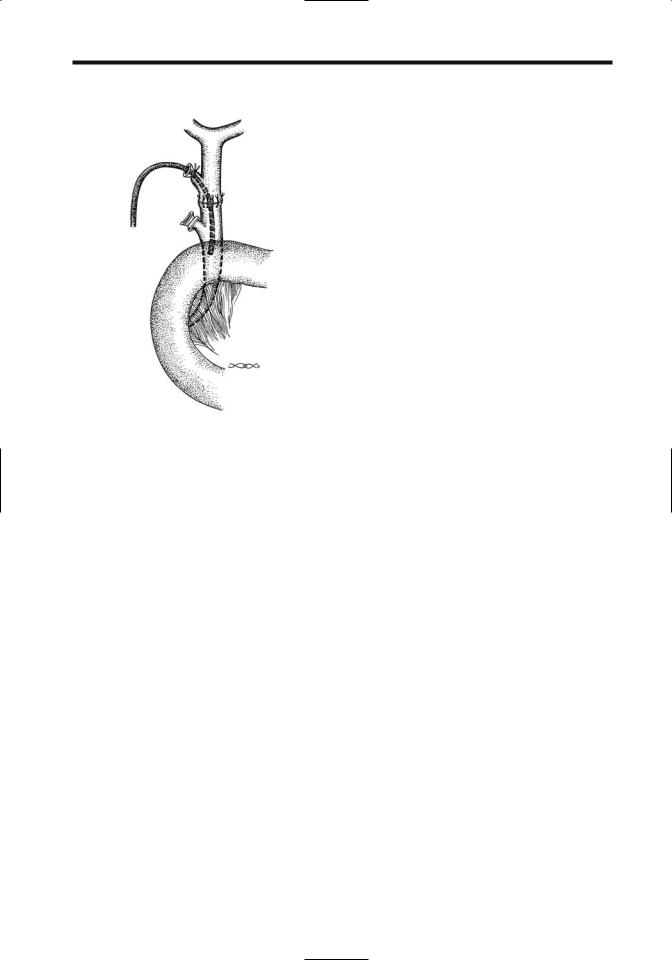

Figure 7.52. Appearance of a choledochocholedochostomy after liver transplantation. Two cystic duct stumps are evident, with a choledochal tube inserted into the proximal (transplant) one.

giogram was obtained in 92% even when intrahepatic bile ducts were not dilated.

Acute: The most common early biliary complication is biliary leakage, usually at an anastomosis. Some leaks manifest only after T-tube removal. A less common cause of bile leak is liver biopsy. Most bilomas are amenable to nonsurgical therapy, but one must ensure that a fluid collection does indeed represent bile rather than a vascular aneurysm; the latter is excluded with Doppler US.

The bile ducts receive their entire blood supply from the hepatic artery and are rather sensitive to ischemia. Thus the risk of biliary complications increases considerably with hepatic artery stenosis. Ischemic complications include leaks, strictures, and adjacent abscesses, with the most common complication being a nonanastomotic biliary stricture. In patients with complete interruption of arterial blood flow, about half also have a biliary complication.

Acute obstruction also occurs due to mechanical T-tube malposition or bile duct kinking. Partial donor cystic duct remnant obstruction and distention due to retained mucus or sludge (mucocele) occasionally compresses the adja-

cent hepatic duct. Ultrasonography reveals a cystic duct mucocele as an anechoic ovoid structure adjacent to bile duct. Such cystic duct mucoceles develop in a small minority of transplanted livers.

Acute biliary complications are usually evaluated by cholangiography. The role of US is controversial. In general, an abnormal US finding is predictive of biliary obstruction with a high specificity, but normal US findings do not exclude a biliary stricture or bile leakage.

Chronic: A biliary stricture is the most common long-term complication after liver transplantation. Stenoses occur most often in the recipient common bile duct, followed by the donor liver common bile duct and anastomotic site. Nonanastomotic strictures presumably are secondary to ischemia. Stones develop proximal to some stenoses.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is a viable option in detecting late biliary complications. More invasive biliary procedures are then reserved either if MRCP does not define underlying anatomy or if interventional procedures are contemplated.

Biliary strictures are readily dilated using interventional radiology techniques. Although a success rate up to 90% can be achieved in dilating these strictures, they tend to recur. The success rate of dilating restenoses is generally lower than for an initial stenosis, and stents should be considered in this setting. Although some stents do obstruct by sludge and debris, their patency can be maintained by various interventional maneuvers.

Intrabiliary defects consist of sludge, stones, and necrotic debris.

Surprisingly, cholangitis is not common. Pancreatitis is rare.

Vascular Complications

Arteriography is the accepted gold standard in evaluating vascular complications, although both CT and US detect some complications. Multislice 3D CT angiography with volume rendering, in particular, is a promising approach in these patients. Currently, however, for suspected vascular complication Doppler US is more common than CT or MR. For therapeutic interventions an angiographic approach is necessary.

Magnetic resonance angiography is assuming a greater role in evaluating vascular anasto-