BRITAIN REFORMED

1509–1603

The Tudors presided over a century in which Britain was reformed in almost every aspect. The most dramatic change was in the church, but there was also a revolution in government (both in the English monarchy and in the British state), and wide-ranging social and intellectual change. Henry Tudor was perhaps an unlikely progenitor of such sweeping alterations. He himself was not a reformer, but rather a skillful manager of existing institutions. As seen in the last chapter, his reign as Henry VII (1485–1509) was notable for the restoration of stable royal administration. He prepared the ground for his son by accumulating a surplus in the treasury, affirming the Crown’s authority over the aristocracy and Parliament, strengthening royal courts of law, and avoiding costly military adventures. Finally, he assured the succession of his younger son Henry and arranged for the renewal of an alliance by marriage with Spain.

THE TUDOR DYNASTY

Henry VIII (1509–47) had much grander visions of his role than were ever entertained by his father. He thought that his realm should share the stage of European power with France and Spain and that the royal succession justified all manner of expedients, including a succession of royal wives and a reform of the church. Henry’s reign began smoothly enough, as he carried out his father’s wish and married Catherine of Aragon in 1509. She and Henry had five children, but only Princess Mary survived infancy. In search of a male heir, Henry decided to divorce Catherine, a process that took six years (1527–33) and led to England’s break with the Roman Catholic Church. As head of the new Church of England, Henry married Anne Boleyn, who gave birth to Princess Elizabeth in 1533. Anne was found guilty of treason and executed. She was replaced by Jane Seymour, who gave birth to Prince Edward but died afterward (1537). Henry later married and divorced Anne of Cleves (1540); married Catherine Howard, who was executed for adultery (1540–42); and finally married Catherine Parr in 1543, who survived him.

Henry’s ambition in international affairs was as ill-conceived as his marital conduct. Dreaming of victory in France, he invaded in 1512, captured Tournai, and married his sister Mary to Louis XII. But the cost of the war (which also led

20

Britain Reformed 21

to the defeat of the French allies, the Scots, at Flodden in 1513) was its most serious result. In 1518 Henry and Cardinal Wolsey devised the Peace of London, leading to a temporary balance of power in Europe. But when a Spanish Habsburg became Holy Roman Emperor (Charles V in 1519), that illusion evaporated. Henry engaged in another diplomatic fantasy in 1520, meeting the French king Francis I at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, near Calais. This was a summit meeting, arranged with inordinate display and again designed to promote Henry’s international importance, but it mainly resulted in a drain on the

Portrait of Henry VIII

(Hulton/Archive)

22 Great Britain

treasury. Further campaigns against France and Scotland marked the last 20 years of his reign, all to no effect.

Henry’s personality was morbid, suspicious, and brutal. Wives, officials, clergymen, and suspected enemies were in mortal danger. The king had less to fear from court intrigues, rebels, or foreign agents than they had to fear from him. In his will, Henry directed that his son and successor Edward VI (1547–1553) have a council and no one adviser as a regent or protector. Edward Seymour, uncle to Edward and duke of Somerset, nevertheless assumed a protectorate. The duke pursued the fulfillment of the Treaty of Greenwich (1543), which was supposed to arrange the marriage of Edward to his cousin Mary of Scotland, daughter of James V. This policy was thwarted by French diplomacy, and Seymour was overthrown in 1549 by John Dudley, duke of Northumberland, who was protector for the rest of Edward’s reign. As the king’s protectors and his royal council were strong supporters of Protestant reform, the Church of England moved much further away from Roman Catholicism during these years. Edward himself never took power in his own right, as he became ill and died at the age of 15. Before his death, Northumberland persuaded the king to designate Lady Jane Grey (the duke’s daughter-in-law) as his successor. But those loyal to Princess Mary defeated this coup attempt.

Mary I (1553–58) was a devout Roman Catholic, spurned by the court and sometimes in mortal danger as she grew up. Her goal was to restore the old church, and she tried to advance that cause by undoing the legislation and policy of the previous two reigns. Her most ambitious move, however, was to marry King Philip of Spain, thus creating a dynastic union that would endow any heir with the strongest ties to the papacy and the traditional church. But the marriage was not successful; Philip lost interest in his bride, and while Mary was sure she was carrying his child, she was in fact dying of stomach cancer. Her death came in the midst of the efforts to undo the reformation, and it gave the throne to her Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth.

Elizabeth I (1558–1603), the daughter of Anne Boleyn, had lived in an unstable situation for much of her early life. Declared illegitimate by her father in 1537, and suspected by her half-sister of being a plotter, she had learned to conduct herself in a circumspect fashion. Her own religion inclined toward the traditional features of Catholic worship, but she adopted the royal supremacy and limited aspects of the reformed religion. Elizabeth chose what some called a “via media,” or middle way, between Catholic and Protestant. She did have herself styled as “supreme governor” of the church, and she allowed much of the reformers’ agenda to be followed. But in this and other areas of policy— especially questions about her designs for a husband—Elizabeth was careful to conceal her true opinions. This was very helpful in staving off excommunication until 1570. Even after that, the catholic powers held back from a full assault, until in 1586 Philip of Spain decided to launch his armada católica against England. This decision was followed by the queen’s anguished choice to execute her cousin Mary, queen of Scots, for plotting against her. Elizabeth’s admirals succeeded in beating the Spanish Armada in 1588, and some later fleets were turned back by weather and other problems. Thus England was

Britain Reformed 23

spared an invasion, while her privateers and explorers harassed Spanish treasure fleets and made early forays into American exploration and colonization. Elizabeth harbored none of her father’s illusions about English power, but her reign saw the development of English maritime strength. Elizabeth never married, never had a child, and at the end she named her cousin Mary’s child, James VI of Scotland, as her successor. With this the Tudor dynasty ended, and the Stuart dynasty began.

The Tudors, particularly Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, guided the realm toward significantly new destinations. Their calculated plans were not all successful, but the end result for Britain was a striking set of new institutions and ideas, the most important being the formation of the Church of England.

THE CHURCH REFORMED

The Church of England was the product of what is called the English Reformation. That series of events was essentially the conversion of the church from a branch of the Western Christian Church to a department of the English state. Its immediate cause was Henry VIII’s struggle to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. However, that struggle occurred within a context of popular discontent with the church, humanist scholarship and debate, and continental Protestant reform movements. Therefore, the “Henrician” reformation, as it is sometimes called, was tied to many different, and sometimes unrelated developments, and its explanation must try to describe each of them.

There was widespread discontent within the English Christian community in the early 16th century. Whether it was sufficient to support a broad Protestant movement may be doubted, but there was a good deal of anticlerical feeling: a perception that there was an excessive number of clergy and that they absorbed large amounts of resources (tithes, rents, and fines) was accompanied by stories of inefficiency (clergy holding multiple benefices and not residing in them) and tales of injustice at the hands of church courts. A second problem was the formality and impersonal nature of religious worship, symbolized by the reading of the Latin mass to uncomprehending worshippers. More personalized worship by individuals, whether reading scripture or private meditation, was only available to the wealthier educated class. With Erasmus’s Handbook of a Christian Knight (1503), or his satire In Praise of Folly (1514), the English reader found devotional guidance and subversive entertainment; but again, that audience was severely limited in size.

The “king’s great matter” (his divorce from Catherine of Aragon) gave the ignition to reform, although it was not expected to have that effect. Indeed, in 1521 Henry VIII wrote a pamphlet attacking Martin Luther’s heretical views, called The Defense of the Seven Sacraments. The pope bestowed the title “defender of the faith” (fidei defensor) on the king, a title which ironically is still used on British coinage. Henry conceived of himself as something of a theologian, and when he decided to discard his wife Catherine in 1527, he marshaled several biblical arguments and urged Cardinal Wolsey to convince the pope that the annulment was correct. Such a concession was indeed common for royalty and aristocrats, but in

24 Great Britain

this case the pope had to invalidate his predecessor’s dispensation allowing Henry to marry his brother’s widow. The matter was complicated by the fact that Catherine’s nephew, the Holy Roman Emperor, happened to have an army in control of Rome at the time. All of Wolsey’s efforts to win a trial and verdict in the king’s favor failed, and he died soon after being removed from office.

A member of Wolsey’s staff, Thomas Cromwell, soon became Henry’s chief advisor in church matters. He conducted a clever campaign to coerce the clergy into submitting to the king, prior to issuing directives and introducing legislation that gave the king supreme authority over the church in England. There was a series of legislative acts that denied revenues to Rome, terminated Roman legal authority, and finally declared the king to be the “supreme head” of the church. This involvement of Parliament as the vehicle for the king’s directives gave that body the appearance of greatly increased power. But for the time being, Henry was the principal beneficiary, and he used the oaths recognizing his supremacy as a tool to beat down his adversaries, such as his lord chancellor, Sir Thomas More; his bishops, including John Fisher; and other members of the church, such as the Carthusian monks of London—all of whom were executed by the king in 1535. The supreme head of the church could not tolerate the divided loyalty of the monks and friars, who were by definition under direct Roman authority. Hence, in 1535 Cromwell made a survey, the valor ecclesiasticus, which assessed the value of monastic properties and the management of their assets. This was used as a pretext for dissolving the houses, first the smallest and then the rest (1536–38). A reaction to the dissolution took place in the Pilgrimage of Grace (1536), a popular demonstration against the destruction of monastic houses. Henry promised leniency to the pilgrimage’s leaders, but they were arrested and executed.

While the pretext for dissolution was to discipline errant monks, the purpose was to seize their wealth. Most of it was soon spent on the king’s wars or granted to members of the landowning class. Some was used to found schools, almshouses, and hospitals. The spoliation of the monasteries was a crude exercise in public looting, worthy of a rabid reform, but the king’s policy was still not of that type. He reluctantly authorized the English Bible in parish churches in 1539, a few years after his agents had hunted down William Tyndale, who was responsible for the first English translation of the New Testament. His archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, worked on a Book of Common Prayer, but it was not produced until after the king’s death. Meanwhile, numerous articles of religion were adopted, with later alterations in the 1530s and 1540s. The upshot of the Henrician reformation was the total reorganization of the Church of England under the authority of its “supreme head,” without coherent attention to change in doctrine.

This new Church of England was not the only reformed church in the British Isles, for of course the church in Wales, Scotland, or Ireland could hardly be insulated. Each of the other three areas had a unique experience. Since Wales was part of the English province of Canterbury, it was subject to all of the reforms instituted in England. There were pockets of resistance, just as there were in England, and Cromwell decided that the annexation of Wales was

Britain Reformed 25

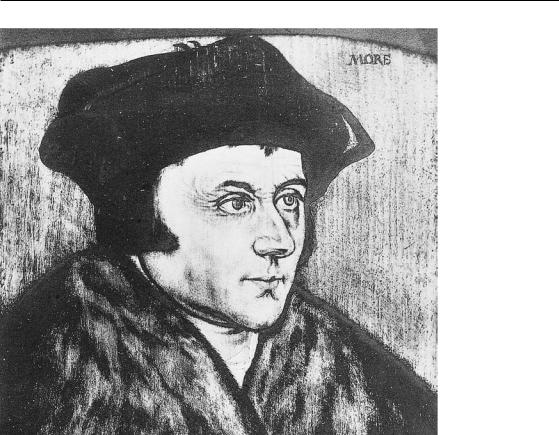

Sir Thomas More

(Library of Congress)

required in order to better secure the settlement there. Ireland was directed to adopt the English changes, but only the Pale, that part of Ireland under English control, was likely to be affected. Moreover, the majority of the Irish church remained Catholic and was likely to provide a strong base for papal reaction. The reformed church was definitely in a minority position, even though it wielded the apparent powers of the state. In Scotland, the church was under the Scots crown and influenced by the French alliance. Thus it was resistant to reforms, but when the French retired and Scottish leaders took control in 1560, the country experienced a popular and Protestant reform. These differences reflect the varied pattern of government in the British Isles, a pattern which itself was being reformed in the 16th century, both in the English center and in the British periphery.

THE ENGLISH MONARCHY REFORMED

About 50 years ago a thesis was advanced that during the 16th century there was a “revolution in government”—a shift from medieval to modern—in

26 Great Britain

church, Parliament, and administration in England. There has been much debate and many amendments to the thesis, but the basic argument seems sound. The royal government of Henry VIII became something very different from its predecessors, and the modern elements, though buffeted over the next 150 years, remained visible and vital.

At the center of this revolution, Thomas Cromwell took old offices, combined them and their revenues, and applied new and more efficient accounting and management methods. He also reformed the king’s privy (private) council, forming a smaller and more efficient body to effectively manage the newly empowered Parliament, which alone could produce (at the king’s behest) the new statutes, so vital to the functioning of the reformed government. When Cromwell was deposed in 1540, a clerk to the council was appointed, and a regular register of council acts was begun.

These changes were not so surprising when it is seen that the problems of the 15th century had to do with the ability of powerful aristocrats to overawe the royal councils and intimidate royal officials. At first, under Henry VII, the council was an important new judicial forum. Sitting as the Court of Star Chamber, or the Court of Requests, the king’s councillors heard cases against powerful subjects or, in the second case, on behalf of poor persons, and administered justice outside the rules of the common law courts. Beside the obvious tension this created in the judicial sphere, these prerogative courts were a notable addition to royal authority.

Thus, some change was already under way when the storm of the Reformation blew through the English government. Several major governmental changes can be tied directly to the church’s reform. First, the powerful church- men—the extreme example being Cardinal Wolsey as the lord chancellor— would never again dominate the highest level of civil government. Second, the former wealth of the church, a basis for its role in public affairs, was put directly under the control of the Crown and, in the case of the dissolution, converted to civil uses. That process was managed by new secular courts, the Court of Augmentations (1536) and a Court of First Fruits and Tenths (1540), coupled to a Court of Wards (1540) for feudal revenues and a Court of General Surveyors (1542). These bodies were an attempt to bypass the ancient Court of Exchequer, to give the Crown more direct control over revenues. A third change, which did not last, was the creation of a secular manager of church affairs. “The King’s Vicegerent for Spirituals” was Cromwell’s title, and in this capacity he ordered the important survey of monastic properties that preceded the dissolution. The importance of the title is that it is more evidence of the radical experimentation then being undertaken, particularly in connection with church reform.

The further argument for revolution hinges on the work of Cromwell, and of some of his successors, in creating the post of secretary of state. The king’s chief officer had been the lord chancellor, who was the keeper of the great seal; head of the chancery or writing office, and as such the nominal supervisor of royal correspondence; and the head of the Court of Chancery, the court of equity jurisdiction. In the 1530s Cromwell held the office of king’s secretary,

Britain Reformed 27

and under him an attempt was made to supplant the clerical functions of the chancellor. The emergence of a new office that managed the king’s business in more efficient manner was undeniably important. This post would be used by a later Tudor servant, William Cecil, Lord Salisbury, to establish the post of secretary of state, a major position in modern government.

Cromwell’s work also influenced the unique English system of local government, which depended on the unpaid services of the justices of the peace in each county. He sent circular letters to the justices of the peace (JPs) in the king’s name, handwritten by his clerks. These directives, coupled to the reports he received from the JPs and justices on circuit, created a network of government with two novel features: it took precedence over the church hierarchy, and it took power away from the many local feudal jurisdictions that had arisen during the Middle Ages.

There are other ways in which royal government, especially that of Henry VIII, was reformed in the mid-16th century. The king’s martial endeavors have been noted, and their expense seems foolish next to a pragmatic view of England’s power in Europe. However, in two ways they added to monarchic reformation: Henry’s ambition prompted him to push for early development of an English royal navy, and the expense of this, plus his other ventures, applied enormous pressure to royal finances. However wasteful, that pressure forced innovation in organization and finance, and these processes continued into the later 16th century. Finally, there was the king’s relationship with Parliament. Historically that body was an enlarged council summoned by kings, mainly for the approval of revenue measures. Certainly that role continued, but with the Parliament that met during the Reformation, there was an important development. The preamble to the Act in Restraint of Appeals (drafted by Cromwell) stated:

This realm of England is an empire and so hath been accepted in the world, governed by one supreme head and king having the dignity and royal estate of the imperial crown of the same . . ., he being also institute and furnished by the goodness and sufferance of Almighty God with plenary, whole, and entire power, preeminence, authority, prerogative and jurisdiction . . .

This act, like all others, was passed at the instigation of the Crown, and with its approval. And yet the action was more than the proverbial rubber stamp. Kings had never included Parliament in the definition of their fundamental power; hereafter they mutually endorsed a stream of statutory definitions and ratifications. Parliament was a very useful tool for the Crown, although a tool that would someday become a check on royal power. The strength of the “imperial crown” was also being employed in other ways in the 16th century, as it extended its power throughout Britain.

REFORMING THE BRITISH STATE

The “empire” cited in Henry’s Act in Restraint of Appeals referred to the myth of an ancient British kingdom, when in fact the Crown was creating a much

28 Great Britain

more modern British state in the middle of the 16th century. The driving force was the church’s reformation, which was allied with traditional motives of security and dominion.

The map of the British Isles in 1500 showed an England hedged about with buffer zones: the Scottish borders; the Welsh marches; and, outside Britain, the Irish Pale, the Channel Islands, and Calais. Within England, in fact, there were semiautonomous zones in Chester, Lancaster, and Durham—palatine counties whose feudal authority showed that there was as yet no fully dominant central power in England. These special jurisdictions were similar to the delegated royal authority of the marcher lordships in Wales, wardens of the marches on the Scottish border, and a lord deputy in Ireland. One of the major accomplishments of Tudor rule was the centralization of power at the expense of these jurisdictions.

Edward I had formally annexed the principality of Wales, and most of the country was held by marcher lords, perhaps as many as 130 of them in the early 16th century. During Henry VIII’s reign it was decided to end those lordships and bring all of Wales into the system of shires, with members of Parliament and with the institutions of local government and laws as they were in England. This process was completed by statutes in 1536 and 1543. The stated reason was to end disorder and bring good government to Wales. But the real aim was to secure the country against a backlash directed at the Reformation and the dissolution. Wales was already within the English church province of Canterbury, so no new action was required on that front. But the possibility of papal counterattack was taken seriously.

Irish government, or that of the small area around Dublin known as the Pale, was in the hands of a lord deputy, an Anglo-Irish nobleman ruling in the king’s name. Under Henry VIII this system was replaced by English deputies, and the king himself assumed the title king of Ireland in 1541. No such simple step would solve the myriad problems of Irish rule, but this was part of a larger effort to import the reformed church and to extend English-style government institutions to the Irish. These measures had limited success, and only the creation of plantations (with English and Scottish settlers) and the military defeat of Irish clan leaders would eventually give English authority effective control, which was achieved by the end of the Elizabeth I’s reign.

With Scotland the English king faced a poor but formidable adversary. The Tudors managed to complete the Scots’ military defeat, which Edward I had sought. But even though the English destroyed Scottish armies at Flodden (1513) and Solway Moss (1542), and both cases resulted in the death of the Scottish king (James IV and James V, respectively), the Scots remained independent. Part of the reason for this was their alliance with France; the other part was their bitter hatred of the English. This was given renewed life when Henry VIII invaded in the 1540s, attempting to force the dynastic union set out by the Treaty of Greenwich. But Edward VI never married Mary, who briefly became the bride of the king of France. It was Elizabeth who smoothed the road to union by negotiating the withdrawal of the French and English armies from Scotland in 1560. England and Scotland would ultimately be joined through the royal

Britain Reformed 29

marriage of English princess Margaret to Scottish king James IV, arranged by Henry VII in 1503. The unifier would be their great-grandson, the son of Mary, queen of Scots. When his mother abdicated he became James VI of Scotland (1567), and at Elizabeth’s death he became James I of England (1603).

In the week Elizabeth died, the Irish who had fought against her in Hugh O’Neill’s rebellion in Ulster surrendered to the English deputy. This brought the English conquest of Ireland to a conclusion. England now commanded all of the British Isles, although the new king of “Great Britain” would find that many liabilities came with these assets.

THE ELIZABETHAN AGE

Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603) had the longest reign of any Tudor and oversaw the Church of England’s settlement, victory over the Spanish Armada, and less dramatic but equally important economic and social changes during the 16th century. The Elizabethan Age, as it was known, also witnessed the flowering of intellectual life known as the English Renaissance.

The church’s settlement was the climax of the English reformation after the turmoil of Henry VIII’s break with Rome and the succeeding swings under Edward and Mary. The Marian bishops would not serve under Elizabeth, and the exiles who began returning from Geneva and elsewhere were determined to build a sound Protestant church. The queen’s dexterity and determination produced a moderate settlement, one in which she took the title “supreme governor” of the church. In 1559 a prayer book was adopted, much like that of 1552. An Act of Uniformity of 1559 put the enforcement powers of the civil government behind the new church. But its detailed doctrine was still to be decided. In a convocation in 1563 this was hammered out in the 39 Articles of Faith, which had just enough ambiguity at critical points that most of the diverse Protestant flock could support them. Elizabeth’s via media resulted in powerful challenges from both Protestant and Catholic adversaries. From the Protestants came continuing agitation over clergy vestments, forms of prayer, and the allowance for individual interpretation. The last of these led Elizabeth to sack Archbishop Edmund Grindal in 1583 and to promote John Whitgift, who became a symbol of Puritan persecution in the queen’s later years. On the Catholic side, Elizabeth had to deal with a rebellion of nobles in the north in 1569, her own excommunication in 1570, and a series of plots against her life, ending with the trial and execution of her cousin Mary, queen of Scots, in 1587.

The most serious threat to Elizabeth, and to her Protestant subjects, was the Spanish Armada in 1588. Philip of Spain had had hopes of taking Elizabeth as his wife after her sister Mary died. But as this prospect faded, it seemed that the Catholic Mary of Scotland might become queen, especially when, in 1562, Elizabeth was stricken with smallpox; however, she managed to recover. There were a number of plots aimed at bringing about Mary’s succession. By 1570 Elizabeth had been excommunicated, and as a heretic she became a legitimate target. Yet it was not until 1585 that Philip declared war on England and set in motion his plan of conquest. He prepared a giant fleet to sail into the English

30 Great Britain

Engraving of

Queen Elizabeth I

(Library of Congress)

Channel and rendezvous with an army under his lieutenant, the duke of Parma, governor of the Netherlands. The armada would shield the army’s channel crossing. If that trained force of 30,000 had landed, there is little doubt that it could have overthrown the Elizabethan regime. But the English escaped this fate for several reasons. First, an expedition in 1587 had attacked the port of Cádiz and destroyed some of the Spanish fleet’s stores and equipment. Second, when the armada arrived in the channel in 1588, English long-range guns and tactics proved effective against the closed mass of Spanish ships. Third, when

Britain Reformed 31

the armada anchored at Calais, the English launched fire-ships into the fleet at night, causing havoc. The next day the disorganized Spanish were beaten in the Battle of Gravelines and forced to retreat by sailing around the north of the British Isles. There were several later attempts to mount a similar attack, but none got as far as this, and the victory became a celebrated moment in English naval history. Equally important, though, was the cost of this venture combined with the other expeditions and campaigns of Elizabeth’s reign. Some estimates put the cost of the war against Spain at £250,000 per year. On top of that, the queen ordered expeditions to France and Holland to aid Protestants and campaigns in Ireland to suppress the Gaelic rebels there. She sold off vast amounts of Crown lands, spent the income from privateers, borrowed heavily, and left a debt of £400,000 at her death. In short, the kingdom’s finances suffered, and the expedients used to deal with the problem (grants, sales of offices, new taxation) caused escalating discontent and government weakness.

Government finance faltered in the context of a rapidly changing economy. The population had begun to grow again, and it doubled by the end of the 16th century. At the same time there was astronomical inflation—a 500 percent increase over the course of the century. Real wages fell about 50 percent, and that translated into severe pressure on jobs and a rapid increase in vagrancy. Landowners were under pressure to increase production and profits, forcing many to enclose their land, among other things to convert from crops to pasture, in hopes of greater profits.

Elizabethan society proved resilient throughout this period of rapid religious, economic, and political change. The essential hierarchy of social ranks did not change. The aristocracy consisted of peers, knights, esquires, and gentlemen, amounting to about 5 percent of the population. The vast majority of the elite were the gentlemen, or “gentry,” an amorphous, ill-defined group covering a wide range of wealth and position that provided the bulk of the magistrates and clergy. Below the aristocracy were the “middling sort” of people: merchants, farmers, and craftsmen who made up probably 20 percent of the population. They directed most of the business of society, managed estates, carried on trade, and produced the necessary tools for daily work. The poorer sort, including farm workers, laborers, and the poor, made up the remaining 75 percent.

This society, or at least its upper ranks, experienced a further kind of reform over the course of the 16th century, one which often bears the label “renaissance.” The advent of humanist scholarship combined with Tudor patronage and display were the engines of a major reform of education, the arts, and literature. The church’s reformation was a counterpoint that involved displacement of the arts, the libraries, and the trappings of the old faith into a more public arena. In the later decades of the century, the Elizabethan period saw a revival of patronage, royal and aristocratic, which supported the flourishing construction of country houses and the literary work of Sir Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser, and the great William Shakespeare, among others. The century had also seen a notable increase in schools, from the humanist John Colet’s foundation at Westminster (1509) to the more humble town grammar schools, especially numerous after the dissolution of the monasteries caused the loss of

32 Great Britain

many schools. Religion remained the centerpiece of the newer schools. The catechism might be altered, but its method and purpose lost no importance. Elementary schooling probably expanded its audience, but the numbers were small; advanced schooling in Latin—and, less often, Greek grammar—was for an elite destined for the university and, primarily, for the church. As with schools, so the universities went from church to secular control, though with no less emphasis on their divine vocation. Indeed, humanists thought the universities were not fit to train a true gentleman, but as the best established scholarly bodies they became the training schools of the new gentry as well as the vocational schools of the church.

The Tudor era brought a compound of reforms. Settling the Church of England was the central change, and the sometimes brutal impact on society, education, and culture sent shock waves through all of Britain. These waves coincided with secular alterations in the functioning of the English monarchy and in the government of the regions. The new state and society reached a peak of cultural development in Elizabeth’s reign, but her government was weakened by financial erosion while society was still bitterly divided by religious conflict. That combination became the fuel for a century of revolution.