- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •Preface

- •What a Crossover Does

- •Why a Crossover Is Necessary

- •Beaming and Lobing

- •Passive Crossovers

- •Active Crossover Applications

- •Bi-Amping and Bi-Wiring

- •Loudspeaker Cables

- •The Advantages and Disadvantages of Active Crossovers

- •The Advantages of Active Crossovers

- •Some Illusory Advantages of Active Crossovers

- •The Disadvantages of Active Crossovers

- •The Next Step in Hi-Fi

- •Active Crossover Systems

- •Matching Crossovers and Loudspeakers

- •A Modest Proposal: Popularising Active Crossovers

- •Multi-Way Connectors

- •Subjectivism

- •Sealed-Box Loudspeakers

- •Reflex (Ported) Loudspeakers

- •Auxiliary Bass Radiator (ABR) Loudspeakers

- •Transmission Line Loudspeakers

- •Horn Loudspeakers

- •Electrostatic Loudspeakers

- •Ribbon Loudspeakers

- •Electromagnetic Planar Loudspeakers

- •Air-Motion Transformers

- •Plasma Arc Loudspeakers

- •The Rotary Woofer

- •MTM Tweeter-Mid Configurations (d’Appolito)

- •Vertical Line Arrays

- •Line Array Amplitude Tapering

- •Line Array Frequency Tapering

- •CBT Line Arrays

- •Diffraction

- •Sound Absorption in Air

- •Modulation Distortion

- •Drive Unit Distortion

- •Doppler Distortion

- •Further Reading on Loudspeaker Design

- •General Crossover Requirements

- •1 Adequate Flatness of Summed Amplitude/Frequency Response On-Axis

- •2 Sufficiently Steep Roll-Off Slopes Between the Filter Outputs

- •3 Acceptable Polar Response

- •4 Acceptable Phase Response

- •5 Acceptable Group Delay Behaviour

- •Further Requirements for Active Crossovers

- •1 Negligible Extra Noise

- •2 Negligible Impairment of System Headroom

- •3 Negligible Extra Distortion

- •4 Negligible Impairment of Frequency Response

- •5 Negligible Impairment of Reliability

- •Linear Phase

- •Minimum Phase

- •Absolute Phase

- •Phase Perception

- •Target Functions

- •All-Pole and Non-All-Pole Crossovers

- •Symmetric and Asymmetric Crossovers

- •Allpass and Constant-Power Crossovers

- •Constant-Voltage Crossovers

- •First-Order Crossovers

- •First-Order Solen Split Crossover

- •First-Order Crossovers: 3-Way

- •Second-Order Crossovers

- •Second-Order Butterworth Crossover

- •Second-Order Linkwitz-Riley Crossover

- •Second-Order Bessel Crossover

- •Second-Order 1.0 dB-Chebyshev Crossover

- •Third-Order Crossovers

- •Third-Order Butterworth Crossover

- •Third-Order Linkwitz-Riley Crossover

- •Third-Order Bessel Crossover

- •Third-Order 1.0 dB-Chebyshev Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Crossovers

- •Fourth-Order Butterworth Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Linkwitz-Riley Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Bessel Crossover

- •Fourth-Order 1.0 dB-Chebyshev Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Linear-Phase Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Gaussian Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Legendre Crossover

- •Higher-Order Crossovers

- •Determining Frequency Offsets

- •Filler-Driver Crossovers

- •The Duelund Crossover

- •Crossover Topology

- •Crossover Conclusions

- •Elliptical Filter Crossovers

- •Neville Thiele MethodTM (NTM) Crossovers

- •Subtractive Crossovers

- •First-Order Subtractive Crossovers

- •Second-Order Butterworth Subtractive Crossovers

- •Third-Order Butterworth Subtractive Crossovers

- •Fourth-Order Butterworth Subtractive Crossovers

- •Subtractive Crossovers With Time Delays

- •Performing the Subtraction

- •Active Filters

- •Lowpass Filters

- •Highpass Filters

- •Bandpass Filters

- •Notch Filters

- •Allpass Filters

- •All-Stop Filters

- •Brickwall Filters

- •The Order of a Filter

- •Filter Cutoff Frequencies and Characteristic Frequencies

- •First-Order Filters

- •Second-Order and Higher-Order Filters

- •Filter Characteristics

- •Amplitude Peaking and Q

- •Butterworth Filters

- •Linkwitz-Riley Filters

- •Bessel Filters

- •Chebyshev Filters

- •1 dB-Chebyshev Lowpass Filter

- •3 dB-Chebyshev Lowpass Filter

- •Higher-Order Filters

- •Butterworth Filters up to 8th-Order

- •Linkwitz-Riley Filters up to 8th-Order

- •Bessel Filters up to 8th-Order

- •Chebyshev Filters up to 8th-Order

- •More Complex Filters—Adding Zeros

- •Inverse Chebyshev Filters (Chebyshev Type II)

- •Elliptical Filters (Cauer Filters)

- •Some Lesser-Known Filter Characteristics

- •Transitional Filters

- •Linear-Phase Filters

- •Gaussian Filters

- •Legendre-Papoulis Filters

- •Laguerre Filters

- •Synchronous Filters

- •Other Filter Characteristics

- •Designing Real Filters

- •Component Sensitivity

- •First-Order Lowpass Filters

- •Second-Order Filters

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass Filters

- •Sallen & Key Lowpass Filter Components

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass: Unity Gain

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass Unity Gain: Component Sensitivity

- •Filter Frequency Scaling

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass: Equal Capacitor

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass Equal-C: Component Sensitivity

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Butterworth Lowpass: Defined Gains

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass: Non-Equal Resistors

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass: Optimisation

- •Sallen & Key 3rd-Order Lowpass: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 3rd-Order Lowpass: Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Lowpass: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Lowpass: Single-Stage Butterworth

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Lowpass: Single-Stage Linkwitz-Riley

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Lowpass: Three Stages

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Lowpass: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Lowpass: Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 6th-Order Lowpass: Three Stages

- •Sallen & Key 6th-Order Lowpass: Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key Lowpass: Input Impedance

- •Linkwitz-Riley Lowpass With Sallen & Key Filters: Loading Effects

- •Lowpass Filters With Attenuation

- •Bandwidth Definition Filters

- •Bandwidth Definition: Butterworth Versus Bessel

- •Variable-Frequency Lowpass Filters: Sallen & Key

- •First-Order Highpass Filters

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Filters

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Highpass Filters

- •Sallen & Key Highpass Filter Components

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Highpass: Unity Gain

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Highpass: Equal Resistors

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Butterworth Highpass: Defined Gains

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Highpass: Non-Equal Capacitors

- •Sallen & Key 3rd-Order Highpass: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 3rd-Order Highpass in a Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Highpass: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Highpass: Butterworth in a Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Highpass: Linkwitz-Riley in a Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Highpass: Single-Stage With Other Filter Characteristics

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Highpass: Three Stages

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Butterworth Filter: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Highpass: Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 6th-Order Highpass: Three Stages

- •Sallen & Key 6th-Order Highpass: Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key Highpass: Input Impedance

- •Bandwidth Definition Filters

- •Bandwidth Definition: Subsonic Filters

- •Bandwidth Definition: Combined Ultrasonic and Subsonic Filters

- •Variable-Frequency Highpass Filters: Sallen & Key

- •Designing Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback 2nd-Order Lowpass Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback 2nd-Order Highpass Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback 3rd-Order Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback 3rd-Order Lowpass Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback 3rd-Order Highpass Filters

- •Biquad Filters

- •Akerberg-Mossberg Lowpass Filter

- •Akerberg-Mossberg Highpass Filters

- •Tow-Thomas Biquad Lowpass and Bandpass Filter

- •Tow-Thomas Biquad Notch and Allpass Responses

- •Tow-Thomas Biquad Highpass Filter

- •State-Variable Filters

- •Variable-Frequency Filters: State-Variable 2nd Order

- •Variable-Frequency Filters: State-Variable 4th-Order

- •Variable-Frequency Filters: Other Orders of State-Variable

- •Other Filters

- •Aspects of Filter Performance: Noise and Distortion

- •Distortion in Active Filters

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: Looking for DAF

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 2nd-Order Lowpass

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 2nd-Order Highpass

- •Mixed Capacitors in Low-Distortion 2nd-Order Sallen & Key Filters

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 3rd-Order Lowpass Single Stage

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 3rd-Order Highpass Single Stage

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 4th-Order Lowpass Single Stage

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 4th-Order Highpass Single Stage

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: Simulations

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: Capacitor Conclusions

- •Distortion in Multiple-Feedback Filters: 2nd-Order Lowpass

- •Distortion in Multiple-Feedback Filters: 2nd-Order Highpass

- •Distortion in Tow-Thomas Filters: 2nd-Order Lowpass

- •Distortion in Tow-Thomas Filters: 2nd-Order Highpass

- •Noise in Active Filters

- •Noise and Bandwidth

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 2nd-Order Lowpass

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 2nd-Order Highpass

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 3rd-Order Lowpass Single Stage

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 3rd-Order Highpass Single Stage

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 4th-Order Lowpass Single Stage

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 4th-Order Highpass Single Stage

- •Noise in Multiple-Feedback Filters: 2nd-Order Lowpass

- •Noise in Multiple-Feedback Filters: 2nd-Order Highpass

- •Noise in Tow-Thomas Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback Bandpass Filters

- •High-Q Bandpass Filters

- •Notch Filters

- •The Twin-T Notch Filter

- •The 1-Bandpass Notch Filter

- •The Bainter Notch Filter

- •Bainter Notch Filter Design

- •Bainter Notch Filter Example

- •An Elliptical Filter Using a Bainter Highpass Notch

- •The Bridged-Differentiator Notch Filter

- •Boctor Notch Filters

- •Other Notch Filters

- •Simulating Notch Filters

- •The Requirement for Delay Compensation

- •Calculating the Required Delays

- •Signal Summation

- •Physical Methods of Delay Compensation

- •Delay Filter Technology

- •Sample Crossover and Delay Filter Specification

- •Allpass Filters in General

- •First-Order Allpass Filters

- •Distortion and Noise in 1st-Order Allpass Filters

- •Cascaded 1st-Order Allpass Filters

- •Second-Order Allpass Filters

- •Distortion and Noise in 2nd-Order Allpass Filters

- •Third-Order Allpass Filters

- •Distortion and Noise in 3rd-Order Allpass Filters

- •Higher-Order Allpass Filters

- •Delay Lines for Subtractive Crossovers

- •Variable Allpass Time Delays

- •Lowpass Filters for Time Delays

- •The Need for Equalisation

- •What Equalisation Can and Can’t Do

- •Loudspeaker Equalisation

- •1 Drive Unit Equalisation

- •3 Bass Response Extension

- •4 Diffraction Compensation Equalisation

- •5 Room Interaction Correction

- •Equalisation Circuits

- •HF-Cut and LF-Boost Equaliser

- •Combined HF-Boost and HF-Cut Equaliser

- •Adjustable Peak/Dip Equalisers: Fixed Frequency and Low Q

- •Adjustable Peak/Dip Equalisers With High Q

- •Parametric Equalisers

- •The Bridged-T Equaliser

- •The Biquad Equaliser

- •Capacitance Multiplication for the Biquad Equaliser

- •Equalisers With Non-Standard Slopes

- •Equalisers With −3 dB/Octave Slopes

- •Equalisers With −3 dB/Octave Slopes Over Limited Range

- •Equalisers With −4.5 dB/Octave Slopes

- •Equalisers With Other Slopes

- •Equalisation by Filter Frequency Offset

- •Equalisation by Adjusting All Filter Parameters

- •Component Values

- •Resistors

- •Through-Hole Resistors

- •Surface-Mount Resistors

- •Resistors: Values and Tolerances

- •Resistor Value Distributions

- •Obtaining Arbitrary Resistance Values

- •Other Resistor Combinations

- •Resistor Noise: Johnson and Excess Noise

- •Resistor Non-Linearity

- •Capacitors: Values and Tolerances

- •Obtaining Arbitrary Capacitance Values

- •Capacitor Shortcomings

- •Non-Electrolytic Capacitor Non-Linearity

- •Electrolytic Capacitor Non-Linearity

- •Active Devices for Active Crossovers

- •Opamp Types

- •Opamp Properties: Noise

- •Opamp Properties: Slew Rate

- •Opamp Properties: Common-Mode Range

- •Opamp Properties: Input Offset Voltage

- •Opamp Properties: Bias Current

- •Opamp Properties: Cost

- •Opamp Properties: Internal Distortion

- •Opamp Properties: Slew Rate Limiting Distortion

- •Opamp Properties: Distortion Due to Loading

- •Opamp Properties: Common-Mode Distortion

- •Opamps Surveyed

- •The TL072 Opamp

- •The NE5532 and 5534 Opamps

- •The 5532 With Shunt Feedback

- •5532 Output Loading in Shunt-Feedback Mode

- •The 5532 With Series Feedback

- •Common-Mode Distortion in the 5532

- •Reducing 5532 Distortion by Output Stage Biasing

- •Which 5532?

- •The 5534 Opamp

- •The LM4562 Opamp

- •Common-Mode Distortion in the LM4562

- •The LME49990 Opamp

- •Common-Mode Distortion in the LME49990

- •The AD797 Opamp

- •Common-Mode Distortion in the AD797

- •The OP27 Opamp

- •Opamp Selection

- •Crossover Features

- •Input Level Controls

- •Subsonic Filters

- •Ultrasonic Filters

- •Output Level Trims

- •Output Mute Switches, Output Phase-Reverse Switches

- •Control Protection

- •Features Usually Absent

- •Metering

- •Relay Output Muting

- •Switchable Crossover Modes

- •Noise, Headroom, and Internal Levels

- •Circuit Noise and Low-Impedance Design

- •Using Raised Internal Levels

- •Placing the Output Attenuator

- •Gain Structures

- •Noise Gain

- •Active Gain Controls

- •Filter Order in the Signal Path

- •Output Level Controls

- •Mute Switches

- •Phase-Invert Switches

- •Distributed Peak Detection

- •Power Amplifier Considerations

- •Subwoofer Applications

- •Subwoofer Technologies

- •Sealed-Box (Infinite Baffle) Subwoofers

- •Reflex (Ported) Subwoofers

- •Auxiliary Bass Radiator (ABR) Subwoofers

- •Transmission Line Subwoofers

- •Bandpass Subwoofers

- •Isobaric Subwoofers

- •Dipole Subwoofers

- •Horn-Loaded Subwoofers

- •Subwoofer Drive Units

- •Hi-Fi Subwoofers

- •Home Entertainment Subwoofers

- •Low-Level Inputs (Unbalanced)

- •Low-Level Inputs (Balanced)

- •High-Level Inputs

- •High-Level Outputs

- •Mono Summing

- •LFE Input

- •Level Control

- •Crossover In/Out Switch

- •Crossover Frequency Control (Lowpass Filter)

- •Highpass Subsonic Filter

- •Phase Switch (Normal/Inverted)

- •Variable Phase Control

- •Signal Activation Out of Standby

- •Home Entertainment Crossovers

- •Fixed Frequency

- •Variable Frequency

- •Multiple Variable

- •Power Amplifiers for Home Entertainment Subwoofers

- •Subwoofer Integration

- •Sound-Reinforcement Subwoofers

- •Line or Area Arrays

- •Cardioid Subwoofer Arrays

- •Aux-Fed Subwoofers

- •Automotive Audio Subwoofers

- •Motional Feedback Loudspeakers

- •History

- •Feedback of Position

- •Feedback of Velocity

- •Feedback of Acceleration

- •Other MFB Speakers

- •Published Projects

- •Conclusions

- •External Signal Levels

- •Internal Signal Levels

- •Input Amplifier Functions

- •Unbalanced Inputs

- •Balanced Interconnections

- •The Advantages of Balanced Interconnections

- •The Disadvantages of Balanced Interconnections

- •Balanced Cables and Interference

- •Balanced Connectors

- •Balanced Signal Levels

- •Electronic vs Transformer Balanced Inputs

- •Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR)

- •The Basic Electronic Balanced Input

- •Common-Mode Rejection Ratio: Opamp Gain

- •Common-Mode Rejection Ratio: Opamp Frequency Response

- •Common-Mode Rejection Ratio: Opamp CMRR

- •Common-Mode Rejection Ratio: Amplifier Component Mismatches

- •A Practical Balanced Input

- •Variations on the Balanced Input Stage

- •Combined Unbalanced and Balanced Inputs

- •The Superbal Input

- •Switched-Gain Balanced Inputs

- •Variable-Gain Balanced Inputs

- •The Self Variable-Gain Balanced Input

- •High Input Impedance Balanced Inputs

- •The Instrumentation Amplifier

- •Instrumentation Amplifier Applications

- •The Instrumentation Amplifier With 4x Gain

- •The Instrumentation Amplifier at Unity Gain

- •Transformer Balanced Inputs

- •Input Overvoltage Protection

- •Noise and Balanced Inputs

- •Low-Noise Balanced Inputs

- •Low-Noise Balanced Inputs in Real Life

- •Ultra-Low-Noise Balanced Inputs

- •Unbalanced Outputs

- •Zero-Impedance Outputs

- •Ground-Cancelling Outputs

- •Balanced Outputs

- •Transformer Balanced Outputs

- •Output Transformer Frequency Response

- •Transformer Distortion

- •Reducing Transformer Distortion

- •Opamp Supply Rail Voltages

- •Designing a ±15 V Supply

- •Designing a ±17 V Supply

- •Using Variable-Voltage Regulators

- •Improving Ripple Performance

- •Dual Supplies From a Single Winding

- •Mutual Shutdown Circuitry

- •Power Supplies for Discrete Circuitry

- •Design Principles

- •Example Crossover Specification

- •The Gain Structure

- •Resistor Selection

- •Capacitor Selection

- •The Balanced Line Input Stage

- •The Bandwidth Definition Filter

- •The HF Path: 3 kHz Linkwitz-Riley Highpass Filter

- •The HF Path: Time-Delay Compensation

- •The MID Path: Topology

- •The MID Path: 400 Hz Linkwitz-Riley Highpass Filter

- •The MID Path: 3 kHz Linkwitz-Riley Lowpass Filter

- •The MID Path: Time-Delay Compensation

- •The LF Path: 400 Hz Linkwitz-Riley Lowpass Filter

- •The LF Path: No Time-Delay Compensation

- •Output Attenuators and Level Trim Controls

- •Balanced Outputs

- •Crossover Programming

- •Noise Analysis: Input Circuitry

- •Noise Analysis: HF Path

- •Noise Analysis: MID Path

- •Noise Analysis: LF Path

- •Improving the Noise Performance: The MID Path

- •Improving the Noise Performance: The Input Circuitry

- •The Noise Performance: Comparisons With Power Amplifier Noise

- •Conclusion

- •Index

Line Outputs 607

The only advantages that this kind of balanced output has over an unbalanced output is that the total signal level on the interconnection is increased by 6 dB, which if correctly handled can improve the signal-to-noise ratio. It is also less likely to crosstalk to other lines, even if they are unbalanced, as the currents injected via the stray capacitance from each line will tend to cancel; how well this works depends on the physical layout of the conductors. All balanced outputs give the facility of correcting phase errors by swapping hot and cold outputs. This is however a two-edged sword, because it is probably how the phase got wrong in the first place.

There is no need to worry about the exact symmetry of level for the two output signals; ordinary 1% tolerance resistors are fine. Slight gain differences between the two outputs only affect the signalhandling capacity of the interconnection by a very small amount. This simple form of balanced output is the norm in hi-fi balanced interconnection but is less common in professional audio, where the quasi-floating output, which emulates a transformer winding, gives both common-mode rejection and more flexibility in situations where temporary connections are frequently being made.

Transformer Balanced Outputs

If true galvanic isolation between equipment grounds is required, this can only be achieved with a line transformer, sometimes called a line isolating transformer; don’t confuse them with mains isolating transformers.You don’t, as a rule, use line transformers unless you really have to, because the muchdiscussed cost, weight, and performance problems are very real, as you will see shortly. However they are sometimes found in big sound-reinforcement systems and in any environment where high RF field strengths are encountered. They are unlikely to be used in active crossovers for domestic hi-fi.

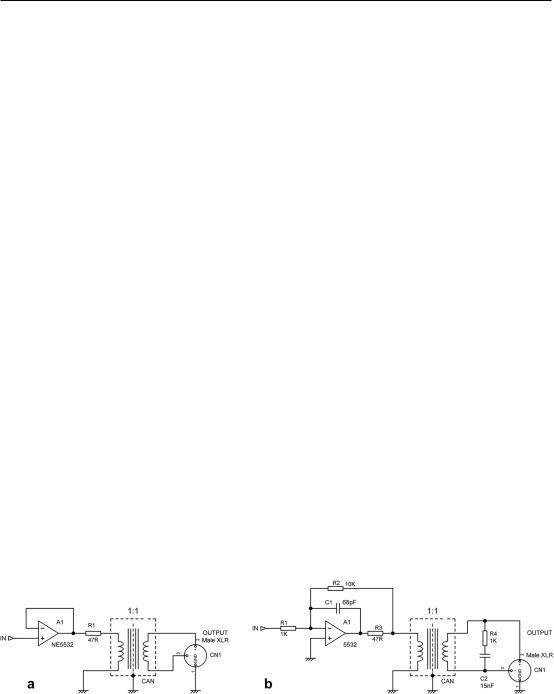

A basic transformer balanced output is shown in Figure 21.4a; in practice A1 would also have some other function such as providing gain or filtering. In good-quality line transformers there will be an inter-winding screen, which should be earthed to minimise noise pickup and general EMC problems. In most cases this does not ground the external can, and you have to arrange this yourself, possibly by mounting the can in a metal capacitor clip. Make sure the can is earthed, as this definitely does reduce noise pickup.

Be aware that the output impedance will be higher than usual because of the ohmic resistance of the transformer windings. With a 1:1 transformer, as normally used, both the primary and secondary winding resistances are effectively in series with the output.Asmall line transformer can easily have 60

Figure 21.4: Transformer balanced outputs: (a) standard circuit; (b) zero-impedance drive to reduce LF distortion, with Zobel network across secondary.

608 Line Outputs

Ω per winding, so the output impedance is 120 Ω plus the value of the series resistance R1 added to the primary circuit to prevent HF instability due to transformer winding capacitances and line capacitances.

The total can easily be 160 Ω or more, compared with, say, 47 Ω for non-transformer output stages.

This will mean a higher output impedance and greater voltage losses when driving heavy loads.

DC flowing through the primary winding of a transformer is bad for linearity, and if your opamp output has anything more than the usual small offset voltages on it, DC current flow should be stopped by a blocking capacitor.

Output Transformer Frequency Response

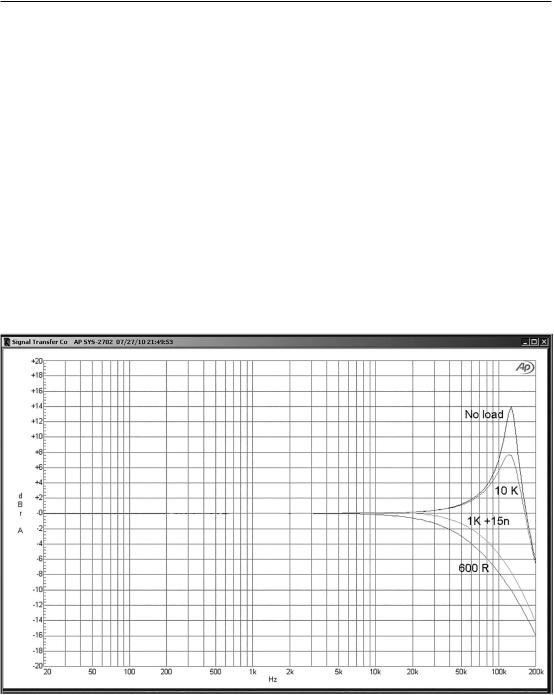

If you have looked at the section in Chapter 20 on the frequency response of line input transformers, you will recall that they give a nastily peaking frequency response if the secondary is not loaded properly, due to resonance between the leakage inductance and the stray winding capacitances. Exactly the same problem afflicts output transformers, as shown in Figure 21.5; with no output loading there is a frightening 14 dB peak at 127 kHz. This is high enough in frequency to have very little effect on the response at 20 kHz, but such a high-Q resonance isn’t the sort of horror you want lurking in your circuitry. It could easily cause some nasty EMC problems.

Figure 21.5: Frequency response of a Sowter 3292 output transformer with various loads on the secondary. Zero-impedance drive as in Figure 21.4b.

Line Outputs 609

The transformer measured was a Sowter 3292 1:1 line isolating transformer. Sowter are a highly respected company, and this is a quality part with a mumetal core and housed in a mumetal can for magnetic shielding. When used as the manufacturer intended, with a 600 Ω load on the secondary, the results are predictably quite different, with a well-controlled roll-off that Imeasured as −0.5 dB at 20 kHz.

The difficulty is that there are very few if any genuine 600 Ω loads left in the world, and most output transformers are going to be driving much higher impedances. If we are driving a 10 kΩ load, the secondary resonance is not much damped, and we still get a thoroughly unwelcome 7 dB peak above 100 kHz, as shown in Figure 21.5. We could of course put a permanent 600 Ω load across the secondary, but that will heavily load the output opamp, impairing its linearity, and will give us unwelcome signal loss due in the winding resistances. It is also profoundly inelegant.

Abetter answer, as in the case of the line input transformer, is to put a Zobel network, i.e. a series combination of resistor and capacitor, across the secondary, as in Figure 21.4b. The capacitor required is quite small and will cause very little loading, except at high frequencies where signal amplitudes are low.Alittle experimentation yielded the values of 1 kΩ in series with 15 nF, which gives the much improved response shown in Figure 21.5. The response is almost exactly 0.0 dB at 20 kHz, at the cost of a very gentle 0.1 dB rise around 10 kHz; this could probably be improved by a little more tweaking of the Zobel values. Be aware that a different transformer type will require different values.

Transformer Distortion

Transformers have well-known problems with linearity at low frequencies. This is because the voltage induced into the secondary winding depends on the rate of change of the magnetic field in the core, and so the lower the frequency, the greater the change in field magnitude must be for transformer action. [1] The current drawn by the primary winding to establish this field is non-linear, because of the well-known non-linearity of iron cores. If the primary had zero resistance and was fed from a zero source impedance, as much distorted current as was needed would be drawn, and no one would ever know there was a problem. But . . . there is always some primary resistance, and this alters the primary current drawn so that third-harmonic distortion is introduced into the magnetic field established and so into the secondary output voltage. Very often there is a series resistance R1 deliberately inserted into the primary circuit, with the intention of avoiding HF instability; this makes the LF distortion problem worse.An important point is that this distortion does not appear only with heavy loading—it is there all the time, even with no load at all on the secondary; it is not analogous to loading the output of a solid-state power amplifier, which invariably increases the distortion. In fact, in my experience transformer LF distortion is slightly better when the secondary is connected to its rated load resistance. With no secondary load, the transformer appears as a big inductance, so as frequency falls the current drawn increases, until with circuits like Figure 21.4a, there is a sudden steep increase in distortion around 10–20 Hz as the opamp hits its output-current limits. Before this happens the distortion from the transformer itself will be gross.

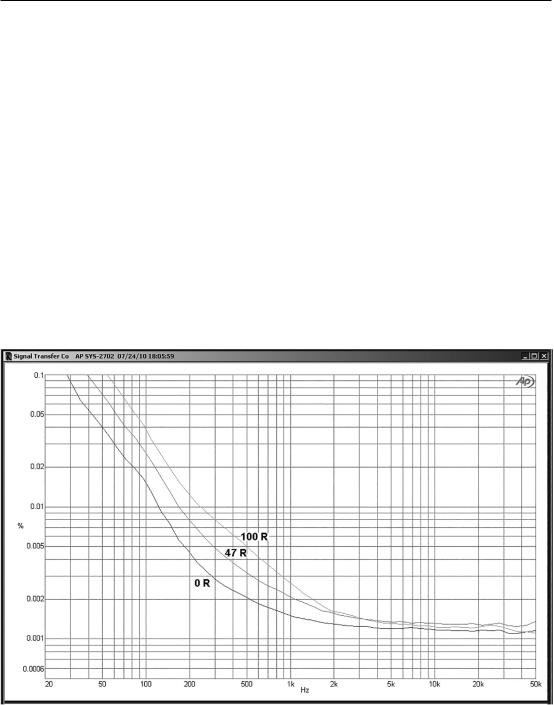

To demonstrate this I did some distortion tests on the same Sowter 3292 transformer. The winding resistance for both primary and secondary is about 59 Ω. It is quite a small component, 34 mm in diameter and 24 mm high and weighing 45 gm, and is obviously not intended for transferring large amounts of power at low frequencies. Figure 21.6 shows the LF distortion with no series resistance,

610 Line Outputs

driven directly from a 5532 output (there were no HF stability problems in this case, but it might be different with cables connected to the secondary), and with 47 and 100 Ω added in series with the primary. The flat part to the right is the noise floor.

Taking 200 Hz as an example, adding 47 Ω in series increases the THD from 0.0045% to 0.0080%, figures which are in exactly the same ratio as the total resistances in the primary circuit in the two cases. It’s very satisfying when a piece of theory slots right home like that. Predictably, a 100 Ω series resistor gives even more distortion, namely 0.013% at 200 Hz, and once more proportional to the total primary circuit resistance.

If you’re used to the near-zero LF distortion of opamps, you may not be too impressed with

Figure 21.6, but this is the reality of output transformers. The results are well within the manufacturer’s specifications for a high-quality part. Note that the distortion rises rapidly to the LF end, roughly tripling as frequency halves. It also increases fast with level, roughly quadrupling as level doubles.

Having gone to some pains to make electronics with very low distortion, this non-linearity at the very end of the signal chain is distinctly irritating.

The situation is somewhat eased in actual use, as signal levels in the bottom octave of audio are normally about 10–12 dB lower than the maximum amplitudes at higher frequencies; see Chapter 17 for more on this.

Figure 21.6: The LF distortion rise for a 3292 Sowter transformer, without (0R) and with (47 Ω and 100 Ω) extra series resistance. Signal level 1 Vrms.