- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •Preface

- •What a Crossover Does

- •Why a Crossover Is Necessary

- •Beaming and Lobing

- •Passive Crossovers

- •Active Crossover Applications

- •Bi-Amping and Bi-Wiring

- •Loudspeaker Cables

- •The Advantages and Disadvantages of Active Crossovers

- •The Advantages of Active Crossovers

- •Some Illusory Advantages of Active Crossovers

- •The Disadvantages of Active Crossovers

- •The Next Step in Hi-Fi

- •Active Crossover Systems

- •Matching Crossovers and Loudspeakers

- •A Modest Proposal: Popularising Active Crossovers

- •Multi-Way Connectors

- •Subjectivism

- •Sealed-Box Loudspeakers

- •Reflex (Ported) Loudspeakers

- •Auxiliary Bass Radiator (ABR) Loudspeakers

- •Transmission Line Loudspeakers

- •Horn Loudspeakers

- •Electrostatic Loudspeakers

- •Ribbon Loudspeakers

- •Electromagnetic Planar Loudspeakers

- •Air-Motion Transformers

- •Plasma Arc Loudspeakers

- •The Rotary Woofer

- •MTM Tweeter-Mid Configurations (d’Appolito)

- •Vertical Line Arrays

- •Line Array Amplitude Tapering

- •Line Array Frequency Tapering

- •CBT Line Arrays

- •Diffraction

- •Sound Absorption in Air

- •Modulation Distortion

- •Drive Unit Distortion

- •Doppler Distortion

- •Further Reading on Loudspeaker Design

- •General Crossover Requirements

- •1 Adequate Flatness of Summed Amplitude/Frequency Response On-Axis

- •2 Sufficiently Steep Roll-Off Slopes Between the Filter Outputs

- •3 Acceptable Polar Response

- •4 Acceptable Phase Response

- •5 Acceptable Group Delay Behaviour

- •Further Requirements for Active Crossovers

- •1 Negligible Extra Noise

- •2 Negligible Impairment of System Headroom

- •3 Negligible Extra Distortion

- •4 Negligible Impairment of Frequency Response

- •5 Negligible Impairment of Reliability

- •Linear Phase

- •Minimum Phase

- •Absolute Phase

- •Phase Perception

- •Target Functions

- •All-Pole and Non-All-Pole Crossovers

- •Symmetric and Asymmetric Crossovers

- •Allpass and Constant-Power Crossovers

- •Constant-Voltage Crossovers

- •First-Order Crossovers

- •First-Order Solen Split Crossover

- •First-Order Crossovers: 3-Way

- •Second-Order Crossovers

- •Second-Order Butterworth Crossover

- •Second-Order Linkwitz-Riley Crossover

- •Second-Order Bessel Crossover

- •Second-Order 1.0 dB-Chebyshev Crossover

- •Third-Order Crossovers

- •Third-Order Butterworth Crossover

- •Third-Order Linkwitz-Riley Crossover

- •Third-Order Bessel Crossover

- •Third-Order 1.0 dB-Chebyshev Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Crossovers

- •Fourth-Order Butterworth Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Linkwitz-Riley Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Bessel Crossover

- •Fourth-Order 1.0 dB-Chebyshev Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Linear-Phase Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Gaussian Crossover

- •Fourth-Order Legendre Crossover

- •Higher-Order Crossovers

- •Determining Frequency Offsets

- •Filler-Driver Crossovers

- •The Duelund Crossover

- •Crossover Topology

- •Crossover Conclusions

- •Elliptical Filter Crossovers

- •Neville Thiele MethodTM (NTM) Crossovers

- •Subtractive Crossovers

- •First-Order Subtractive Crossovers

- •Second-Order Butterworth Subtractive Crossovers

- •Third-Order Butterworth Subtractive Crossovers

- •Fourth-Order Butterworth Subtractive Crossovers

- •Subtractive Crossovers With Time Delays

- •Performing the Subtraction

- •Active Filters

- •Lowpass Filters

- •Highpass Filters

- •Bandpass Filters

- •Notch Filters

- •Allpass Filters

- •All-Stop Filters

- •Brickwall Filters

- •The Order of a Filter

- •Filter Cutoff Frequencies and Characteristic Frequencies

- •First-Order Filters

- •Second-Order and Higher-Order Filters

- •Filter Characteristics

- •Amplitude Peaking and Q

- •Butterworth Filters

- •Linkwitz-Riley Filters

- •Bessel Filters

- •Chebyshev Filters

- •1 dB-Chebyshev Lowpass Filter

- •3 dB-Chebyshev Lowpass Filter

- •Higher-Order Filters

- •Butterworth Filters up to 8th-Order

- •Linkwitz-Riley Filters up to 8th-Order

- •Bessel Filters up to 8th-Order

- •Chebyshev Filters up to 8th-Order

- •More Complex Filters—Adding Zeros

- •Inverse Chebyshev Filters (Chebyshev Type II)

- •Elliptical Filters (Cauer Filters)

- •Some Lesser-Known Filter Characteristics

- •Transitional Filters

- •Linear-Phase Filters

- •Gaussian Filters

- •Legendre-Papoulis Filters

- •Laguerre Filters

- •Synchronous Filters

- •Other Filter Characteristics

- •Designing Real Filters

- •Component Sensitivity

- •First-Order Lowpass Filters

- •Second-Order Filters

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass Filters

- •Sallen & Key Lowpass Filter Components

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass: Unity Gain

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass Unity Gain: Component Sensitivity

- •Filter Frequency Scaling

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass: Equal Capacitor

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass Equal-C: Component Sensitivity

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Butterworth Lowpass: Defined Gains

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass: Non-Equal Resistors

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Lowpass: Optimisation

- •Sallen & Key 3rd-Order Lowpass: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 3rd-Order Lowpass: Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Lowpass: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Lowpass: Single-Stage Butterworth

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Lowpass: Single-Stage Linkwitz-Riley

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Lowpass: Three Stages

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Lowpass: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Lowpass: Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 6th-Order Lowpass: Three Stages

- •Sallen & Key 6th-Order Lowpass: Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key Lowpass: Input Impedance

- •Linkwitz-Riley Lowpass With Sallen & Key Filters: Loading Effects

- •Lowpass Filters With Attenuation

- •Bandwidth Definition Filters

- •Bandwidth Definition: Butterworth Versus Bessel

- •Variable-Frequency Lowpass Filters: Sallen & Key

- •First-Order Highpass Filters

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Filters

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Highpass Filters

- •Sallen & Key Highpass Filter Components

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Highpass: Unity Gain

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Highpass: Equal Resistors

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Butterworth Highpass: Defined Gains

- •Sallen & Key 2nd-Order Highpass: Non-Equal Capacitors

- •Sallen & Key 3rd-Order Highpass: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 3rd-Order Highpass in a Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Highpass: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Highpass: Butterworth in a Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Highpass: Linkwitz-Riley in a Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 4th-Order Highpass: Single-Stage With Other Filter Characteristics

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Highpass: Three Stages

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Butterworth Filter: Two Stages

- •Sallen & Key 5th-Order Highpass: Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key 6th-Order Highpass: Three Stages

- •Sallen & Key 6th-Order Highpass: Single Stage

- •Sallen & Key Highpass: Input Impedance

- •Bandwidth Definition Filters

- •Bandwidth Definition: Subsonic Filters

- •Bandwidth Definition: Combined Ultrasonic and Subsonic Filters

- •Variable-Frequency Highpass Filters: Sallen & Key

- •Designing Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback 2nd-Order Lowpass Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback 2nd-Order Highpass Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback 3rd-Order Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback 3rd-Order Lowpass Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback 3rd-Order Highpass Filters

- •Biquad Filters

- •Akerberg-Mossberg Lowpass Filter

- •Akerberg-Mossberg Highpass Filters

- •Tow-Thomas Biquad Lowpass and Bandpass Filter

- •Tow-Thomas Biquad Notch and Allpass Responses

- •Tow-Thomas Biquad Highpass Filter

- •State-Variable Filters

- •Variable-Frequency Filters: State-Variable 2nd Order

- •Variable-Frequency Filters: State-Variable 4th-Order

- •Variable-Frequency Filters: Other Orders of State-Variable

- •Other Filters

- •Aspects of Filter Performance: Noise and Distortion

- •Distortion in Active Filters

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: Looking for DAF

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 2nd-Order Lowpass

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 2nd-Order Highpass

- •Mixed Capacitors in Low-Distortion 2nd-Order Sallen & Key Filters

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 3rd-Order Lowpass Single Stage

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 3rd-Order Highpass Single Stage

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 4th-Order Lowpass Single Stage

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: 4th-Order Highpass Single Stage

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: Simulations

- •Distortion in Sallen & Key Filters: Capacitor Conclusions

- •Distortion in Multiple-Feedback Filters: 2nd-Order Lowpass

- •Distortion in Multiple-Feedback Filters: 2nd-Order Highpass

- •Distortion in Tow-Thomas Filters: 2nd-Order Lowpass

- •Distortion in Tow-Thomas Filters: 2nd-Order Highpass

- •Noise in Active Filters

- •Noise and Bandwidth

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 2nd-Order Lowpass

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 2nd-Order Highpass

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 3rd-Order Lowpass Single Stage

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 3rd-Order Highpass Single Stage

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 4th-Order Lowpass Single Stage

- •Noise in Sallen & Key Filters: 4th-Order Highpass Single Stage

- •Noise in Multiple-Feedback Filters: 2nd-Order Lowpass

- •Noise in Multiple-Feedback Filters: 2nd-Order Highpass

- •Noise in Tow-Thomas Filters

- •Multiple-Feedback Bandpass Filters

- •High-Q Bandpass Filters

- •Notch Filters

- •The Twin-T Notch Filter

- •The 1-Bandpass Notch Filter

- •The Bainter Notch Filter

- •Bainter Notch Filter Design

- •Bainter Notch Filter Example

- •An Elliptical Filter Using a Bainter Highpass Notch

- •The Bridged-Differentiator Notch Filter

- •Boctor Notch Filters

- •Other Notch Filters

- •Simulating Notch Filters

- •The Requirement for Delay Compensation

- •Calculating the Required Delays

- •Signal Summation

- •Physical Methods of Delay Compensation

- •Delay Filter Technology

- •Sample Crossover and Delay Filter Specification

- •Allpass Filters in General

- •First-Order Allpass Filters

- •Distortion and Noise in 1st-Order Allpass Filters

- •Cascaded 1st-Order Allpass Filters

- •Second-Order Allpass Filters

- •Distortion and Noise in 2nd-Order Allpass Filters

- •Third-Order Allpass Filters

- •Distortion and Noise in 3rd-Order Allpass Filters

- •Higher-Order Allpass Filters

- •Delay Lines for Subtractive Crossovers

- •Variable Allpass Time Delays

- •Lowpass Filters for Time Delays

- •The Need for Equalisation

- •What Equalisation Can and Can’t Do

- •Loudspeaker Equalisation

- •1 Drive Unit Equalisation

- •3 Bass Response Extension

- •4 Diffraction Compensation Equalisation

- •5 Room Interaction Correction

- •Equalisation Circuits

- •HF-Cut and LF-Boost Equaliser

- •Combined HF-Boost and HF-Cut Equaliser

- •Adjustable Peak/Dip Equalisers: Fixed Frequency and Low Q

- •Adjustable Peak/Dip Equalisers With High Q

- •Parametric Equalisers

- •The Bridged-T Equaliser

- •The Biquad Equaliser

- •Capacitance Multiplication for the Biquad Equaliser

- •Equalisers With Non-Standard Slopes

- •Equalisers With −3 dB/Octave Slopes

- •Equalisers With −3 dB/Octave Slopes Over Limited Range

- •Equalisers With −4.5 dB/Octave Slopes

- •Equalisers With Other Slopes

- •Equalisation by Filter Frequency Offset

- •Equalisation by Adjusting All Filter Parameters

- •Component Values

- •Resistors

- •Through-Hole Resistors

- •Surface-Mount Resistors

- •Resistors: Values and Tolerances

- •Resistor Value Distributions

- •Obtaining Arbitrary Resistance Values

- •Other Resistor Combinations

- •Resistor Noise: Johnson and Excess Noise

- •Resistor Non-Linearity

- •Capacitors: Values and Tolerances

- •Obtaining Arbitrary Capacitance Values

- •Capacitor Shortcomings

- •Non-Electrolytic Capacitor Non-Linearity

- •Electrolytic Capacitor Non-Linearity

- •Active Devices for Active Crossovers

- •Opamp Types

- •Opamp Properties: Noise

- •Opamp Properties: Slew Rate

- •Opamp Properties: Common-Mode Range

- •Opamp Properties: Input Offset Voltage

- •Opamp Properties: Bias Current

- •Opamp Properties: Cost

- •Opamp Properties: Internal Distortion

- •Opamp Properties: Slew Rate Limiting Distortion

- •Opamp Properties: Distortion Due to Loading

- •Opamp Properties: Common-Mode Distortion

- •Opamps Surveyed

- •The TL072 Opamp

- •The NE5532 and 5534 Opamps

- •The 5532 With Shunt Feedback

- •5532 Output Loading in Shunt-Feedback Mode

- •The 5532 With Series Feedback

- •Common-Mode Distortion in the 5532

- •Reducing 5532 Distortion by Output Stage Biasing

- •Which 5532?

- •The 5534 Opamp

- •The LM4562 Opamp

- •Common-Mode Distortion in the LM4562

- •The LME49990 Opamp

- •Common-Mode Distortion in the LME49990

- •The AD797 Opamp

- •Common-Mode Distortion in the AD797

- •The OP27 Opamp

- •Opamp Selection

- •Crossover Features

- •Input Level Controls

- •Subsonic Filters

- •Ultrasonic Filters

- •Output Level Trims

- •Output Mute Switches, Output Phase-Reverse Switches

- •Control Protection

- •Features Usually Absent

- •Metering

- •Relay Output Muting

- •Switchable Crossover Modes

- •Noise, Headroom, and Internal Levels

- •Circuit Noise and Low-Impedance Design

- •Using Raised Internal Levels

- •Placing the Output Attenuator

- •Gain Structures

- •Noise Gain

- •Active Gain Controls

- •Filter Order in the Signal Path

- •Output Level Controls

- •Mute Switches

- •Phase-Invert Switches

- •Distributed Peak Detection

- •Power Amplifier Considerations

- •Subwoofer Applications

- •Subwoofer Technologies

- •Sealed-Box (Infinite Baffle) Subwoofers

- •Reflex (Ported) Subwoofers

- •Auxiliary Bass Radiator (ABR) Subwoofers

- •Transmission Line Subwoofers

- •Bandpass Subwoofers

- •Isobaric Subwoofers

- •Dipole Subwoofers

- •Horn-Loaded Subwoofers

- •Subwoofer Drive Units

- •Hi-Fi Subwoofers

- •Home Entertainment Subwoofers

- •Low-Level Inputs (Unbalanced)

- •Low-Level Inputs (Balanced)

- •High-Level Inputs

- •High-Level Outputs

- •Mono Summing

- •LFE Input

- •Level Control

- •Crossover In/Out Switch

- •Crossover Frequency Control (Lowpass Filter)

- •Highpass Subsonic Filter

- •Phase Switch (Normal/Inverted)

- •Variable Phase Control

- •Signal Activation Out of Standby

- •Home Entertainment Crossovers

- •Fixed Frequency

- •Variable Frequency

- •Multiple Variable

- •Power Amplifiers for Home Entertainment Subwoofers

- •Subwoofer Integration

- •Sound-Reinforcement Subwoofers

- •Line or Area Arrays

- •Cardioid Subwoofer Arrays

- •Aux-Fed Subwoofers

- •Automotive Audio Subwoofers

- •Motional Feedback Loudspeakers

- •History

- •Feedback of Position

- •Feedback of Velocity

- •Feedback of Acceleration

- •Other MFB Speakers

- •Published Projects

- •Conclusions

- •External Signal Levels

- •Internal Signal Levels

- •Input Amplifier Functions

- •Unbalanced Inputs

- •Balanced Interconnections

- •The Advantages of Balanced Interconnections

- •The Disadvantages of Balanced Interconnections

- •Balanced Cables and Interference

- •Balanced Connectors

- •Balanced Signal Levels

- •Electronic vs Transformer Balanced Inputs

- •Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR)

- •The Basic Electronic Balanced Input

- •Common-Mode Rejection Ratio: Opamp Gain

- •Common-Mode Rejection Ratio: Opamp Frequency Response

- •Common-Mode Rejection Ratio: Opamp CMRR

- •Common-Mode Rejection Ratio: Amplifier Component Mismatches

- •A Practical Balanced Input

- •Variations on the Balanced Input Stage

- •Combined Unbalanced and Balanced Inputs

- •The Superbal Input

- •Switched-Gain Balanced Inputs

- •Variable-Gain Balanced Inputs

- •The Self Variable-Gain Balanced Input

- •High Input Impedance Balanced Inputs

- •The Instrumentation Amplifier

- •Instrumentation Amplifier Applications

- •The Instrumentation Amplifier With 4x Gain

- •The Instrumentation Amplifier at Unity Gain

- •Transformer Balanced Inputs

- •Input Overvoltage Protection

- •Noise and Balanced Inputs

- •Low-Noise Balanced Inputs

- •Low-Noise Balanced Inputs in Real Life

- •Ultra-Low-Noise Balanced Inputs

- •Unbalanced Outputs

- •Zero-Impedance Outputs

- •Ground-Cancelling Outputs

- •Balanced Outputs

- •Transformer Balanced Outputs

- •Output Transformer Frequency Response

- •Transformer Distortion

- •Reducing Transformer Distortion

- •Opamp Supply Rail Voltages

- •Designing a ±15 V Supply

- •Designing a ±17 V Supply

- •Using Variable-Voltage Regulators

- •Improving Ripple Performance

- •Dual Supplies From a Single Winding

- •Mutual Shutdown Circuitry

- •Power Supplies for Discrete Circuitry

- •Design Principles

- •Example Crossover Specification

- •The Gain Structure

- •Resistor Selection

- •Capacitor Selection

- •The Balanced Line Input Stage

- •The Bandwidth Definition Filter

- •The HF Path: 3 kHz Linkwitz-Riley Highpass Filter

- •The HF Path: Time-Delay Compensation

- •The MID Path: Topology

- •The MID Path: 400 Hz Linkwitz-Riley Highpass Filter

- •The MID Path: 3 kHz Linkwitz-Riley Lowpass Filter

- •The MID Path: Time-Delay Compensation

- •The LF Path: 400 Hz Linkwitz-Riley Lowpass Filter

- •The LF Path: No Time-Delay Compensation

- •Output Attenuators and Level Trim Controls

- •Balanced Outputs

- •Crossover Programming

- •Noise Analysis: Input Circuitry

- •Noise Analysis: HF Path

- •Noise Analysis: MID Path

- •Noise Analysis: LF Path

- •Improving the Noise Performance: The MID Path

- •Improving the Noise Performance: The Input Circuitry

- •The Noise Performance: Comparisons With Power Amplifier Noise

- •Conclusion

- •Index

CHAPTER 19

Motional Feedback Loudspeakers

Motional Feedback Loudspeakers

The use of motional feedback to improve loudspeaker operation is closely related to active crossover technology. The amplifier is usually physically part of the loudspeaker because it is even more closely coupled than an active crossover system. As described in Chapter 1, you can buy an active crossover and matched loudspeaker from CompanyAand between them put a power amplifier from Company B; all you have to do is get the gain right. Motional feedback (MFB), on the other hand, depends critically on loudspeaker characteristics not only to work at all but in some cases to avoid catastrophic instability. Only one company (Yamaha) has released stand-alone amplifiers with a motional feedback capability.

Many loudspeaker problems are caused by the fact that a drive unit cone does not follow exactly the voltage driving it but has a life of its own due to cone inertia and suspension non-linearities; this is further complicated by cone break-up modes, where different parts of the cone are moving independently. Negative feedback can work miracles in controlling precisely the output voltage of a

power amplifier, and it is a logical step to attempt to gain the same iron control over a drive unit cone by sensing its movement and using that to close a negative feedback loop; this promises both a better frequency response and lower distortion. It is however much more difficult to control a speaker cone with negative feedback than it is a simple output voltage. Motional feedback (MFB) for anything other than a full-range driver unit requires the use of an active crossover, because one amplifier can only control the movement of one drive unit. MFB is typically only applied to the LF unit, as this has the largest excursions, creates the greatest amount of distortion, and is generally further removed from being an infinitely rigid zero-mass piston than the MID and HF units. MFB is also relevant to this book because equalisation of the drive units is often necessary.

Despite this promising prospectus, motional feedback has had little success in the marketplace. The best-known example is the Philips 22RH544 loudspeaker, which derived its motional feedback from a small accelerometer mounted on the dust-cap of the LF unit voice coil. This was made and sold for ten years and was undoubtedly a good product, but it failed to trigger a wave of enthusiasm for MFB.

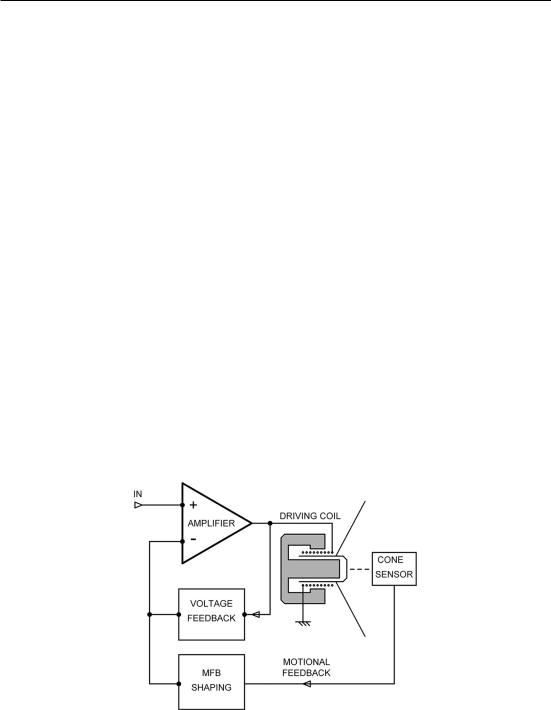

One of the main challenges of MFB is sensing the motion of the drive unit cone without putting any restraint on its movement. The basic idea is shown in Figure 19.1. There are three basic ways to do this:

1.Measure the cone position.

2.Measure the cone velocity.

The velocity can be integrated to get the cone position.

543

544 Motional Feedback Loudspeakers

3. Measure the cone acceleration.

This can be done with a small and light accelerometer. Acceleration can be integrated to get cone velocity and then integrated again to get cone position. The prime example of this is the method used by the Philips 22RH544.

History

As usual, the history of the concept goes back a surprisingly long way. The first reference found was [1] from 1951. See also [2] from 1958 and [3] from 1963. None of these are easy to come by, but a very good early reference that is available is the 1964 Philips Technical Review, [4] which describes the origins of the accelerometer approach.

Feedback of Position

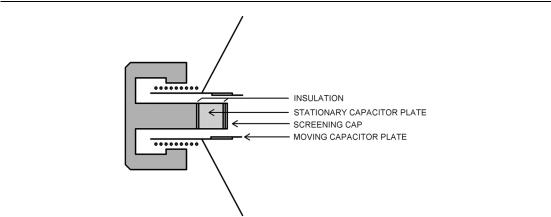

This clearly needs to interfere with cone movement as little as possible; one obvious method that adds very little weight is capacitance sensing. It is not enough simply to fit a conductive dust-cap and place a fixed plate some distance from it; the capacitance is inversely proportional to the distance between the two capacitor plates, and so the position signal will be grossly distorted. An early attempt was by

Brodie in 1958, [5] but as far as I can see it does not address the inverse proportionality. We need a linear change of capacitance with cone position. A neat solution was put forward by ServoSpeaker in 2004 [6][7] and is shown in Figure 19.2. The capacitance depends on the degree of overlap of the moving and fixed plates and is to a first approximation linear.Apatent application was made in

2004, [8] and the technology was described in Hifi-World in 2008, [9] but as far as I can determine no product got to market, and ServoSpeaker no longer seems to exist as a company.

Figure 19.1: The basic principle of motional feedback.

Motional Feedback Loudspeakers 545

Figure 19.2: Motional feedback of cone position using capacitive sensing: ServoSpeaker method.

Ever since I first heard of MFB, it struck me that laser interferometry would be the ideal method; no moving parts added and no extra wires attached to the cone. Laser diodes can’t be expensive, since there’s one in every CD player—how hard can it be? However, I know little of such matters; one person consulted told me that the laser required to get the necessary coherence length would be pretty big—a metre or more long for a frequency stabilised helium-neon laser, which I was told was about the minimum hardware I could get away with. That doesn’t sound too practical; I would be glad to hear if others agree on the possibilities of laser interferometry.

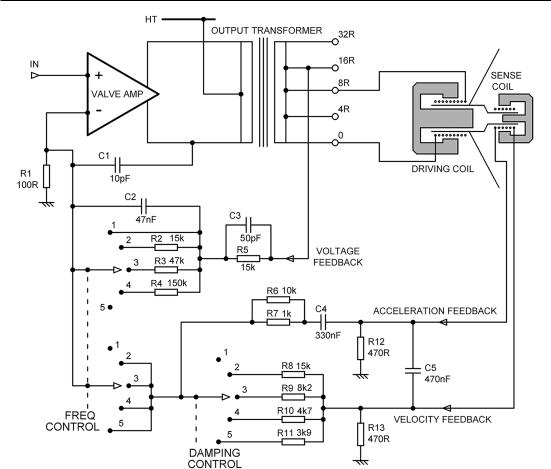

Feedback of Velocity

At first it looks as if this might be easy; a secondary sensing coil is added to the cone primary drive coil and will produce a voltage proportional to its velocity in the magnetic field. The main problem with this approach is transformer coupling between the main voice coil and the sensing coil, which will completely swamp the desired velocity signal. A solution to this which was perhaps clumsy but has a certain no-nonsense appeal was that adopted by Panasonic MF-800 in the early 1960s (see Figure 19.3). [10]Asecond voice coil and magnet were mounted at the front of the drive unit, much reducing transformer action. On reading the user manual it is claimed that MFB reduces “distortion”, but it is not clear if that refers to frequency response errors or non-linear distortion or both. The main aim is clearly to extend the LF response of the loudspeaker, and switches for controlling this were provided, labelled “Frequency” and “Damping”.

There seems no doubt that this method worked as advertised, though according to the manual some control settings gave bass extension combined with a +6 dB resonance peak, which probably did not sound great. This could be suppressed by increasing the damping setting, but this much reduced the bass extension. There are very few references to this system anywhere, which suggests it was not a marketing success. No pictures of the actual drive units have so far been found.

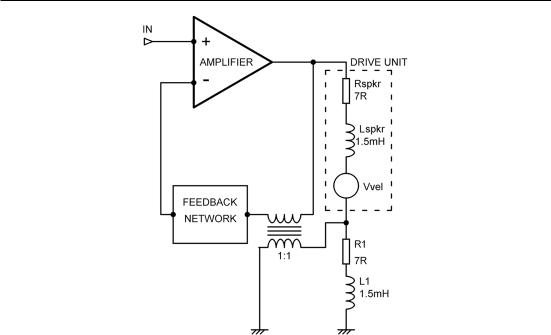

A more subtle and apparently superior approach is to use the same voice coil for both driving the cone and measuring its velocity. The movement of the coil in the magnetic field generates a voltage signal

546 Motional Feedback Loudspeakers

Figure 19.3: Motional feedback of velocity using a separate sense coil and magnet: Panasonic MF-800.

Vvel proportional to the velocity, but this has to be somehow separated out from the voltage driving the speaker. Figure 19.4 shows one way; a balancing impedance R1, L1 is put in series with the drive unit; typical values are shown. The transformer reads the voltage across this load and subtracts it from the main feedback signal so that the velocity signal is isolated and can be added to the feedback as required. Note that the balancing impedance is made equal to the blocked impedance of the drive unit, which is its impedance when the voice coil is fixed so that it cannot move.

This method has a disadvantage which I don’t think I have ever seen explicitly pointed out; as shown it wastes half of the amplifier power that you trustingly feed into it, dissipating it in the balancing impedance. To make this approach practical the balancing impedance must be scaled so it dissipates a small fraction of the power in the drive unit, by raising the transformer ratio or otherwise modifying the feedback arrangements. See [4] for other versions of this circuit.

Motional Feedback Loudspeakers 547

Figure 19.4: Motional feedback of velocity from the voice coil with R1, L1 and the transformer cancelling the drive voltage.

A transformer is not a welcome part in a negative feedback loop; it may have its own linearity problems at low frequencies, and HF phase-shifts are likely to cut down the stability margins.

Figure 19.5 shows a more up-to-date version, where the required subtraction is performed by opamp

A1. The balancing impedance has been scaled down by a factor of seven to demonstrate the process, but the power dissipated in R4 will still be substantial, and further scaling would be desirable. The scaling is embodied in the values of R1, R2, and R3.

This method can also be looked at as making the output impedance of the amplifier negative—it is equal and opposite to the blocked impedance of the drive unit. This should not be confused with current-drive of loudspeakers, where the output impedance is made very high.

This all seems very promising—you can use standard drive units and do the MFB with a few cheap electronic parts. But there are two big problems remaining with voice coil velocity feedback: First, the resistance of a drive unit voice coil changes significantly when it gets hot; a 40% increase is entirely possible with a 100°C temperature rise. This plays mayhem with the impedance balancing, and it would be all too easy to produce a design that became unstable as it heated up, banging the amplifier output against one of the rails. In practice this means that only a small amount of negative feedback can be applied safely.

Second, the uniformity of the magnetic field in which the voice coil moves is imperfect, and this reduces the accuracy of the velocity feedback signal.