8 Conveyancing

Land law is the theory; conveyancing is the practice. For most people, the theory becomes far more intelligible when it is put into practice. Below is a brief, and very simplified, account of a typical house purchase transaction

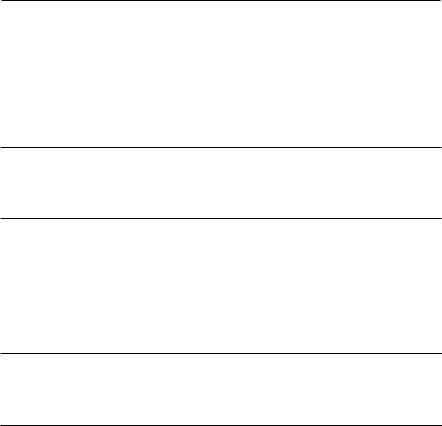

– first under the old, unregistered system of conveyancing, then under the modern, registered system. It is no substitute for real practical experience, but it may assist the imagination of those who lack that advantage. The information is presented in tabular form, followed by an explanation.

A house purchase proceeds in two stages: a contract, by which the parties formally bind themselves to buy and sell; and completion, when the vendor formally transfers his title to the purchaser in fulfilment of the contract. It will be seen that, superficially, there is a close resemblance between a registered transaction and an unregistered transaction. That is only to be expected. The policy of the LRA was to keep differences between the two systems to a minimum But a registered transaction involves far less effort. There are also important differences in the final (pre-completion) searches made by the purchaser’s solicitor and in his post-completion activity.

At the end of 1999, proposals were made which would have the effect of shortening the pre-contract stage of the transaction (when the purchaser is vulnerable to ‘gazumping’). In particular, it was suggested that a vendor be obliged to make a local search and obtain a surveyor’s report before putting his property on the market. These documents would then be immediately available to a prospective purchaser.

In any event, further changes in practice are imminent as the profession moves towards a system of computerised conveyancing.

81

UNDERSTANDING LAND LAW

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CONTRACT |

|

|

COMPLETION |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

UNREGISTERED |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Vendor: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

Vendor: |

|

|

|

|

Vendor: |

|||||||||||

|

– obtain deeds |

|

|

– deduce title |

|

|

|

|

– hand over deeds |

|

|

||||||||

|

– draw contract |

|

|

– reply to requisitions |

|

|

– pay off mortgage |

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– account |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Purchaser: |

|

|

Purchaser: |

|

|

|

|

|

Purchaser: |

|

||||||||

|

– local search |

|

|

– raise requisitions |

– Land Charges |

|

|

|

– pay moneys |

|

|||||||||

|

– prelim enquiries |

|

|

|

|

|

search |

|

|

|

– [complete mortgage] |

|

|||||||

|

– check finance |

|

|

– draw conveyance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– [prepare mortgage] |

|

|

|

|

|

– stamp documents |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– register title |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

REGISTERED |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Vendor: |

|

Vendor: |

|

|

|

|

Vendor: |

|||||||||||

|

– office copies |

|

|

– reply to requisitions |

|

|

|

– hand over deeds |

|||||||||||

|

– draw contract |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– pay off mortgage |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– account |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Purchaser: |

|

Purchaser: |

|

|

|

|

|

Purchaser: |

||||||||||

|

– local search |

|

|

|

– raise requisitions |

– Land Registry |

|

|

|

– pay moneys |

|

||||||||

|

– prelim enquiries |

|

|

|

|

|

search |

|

|

|

– [complete mortgage] |

|

|||||||

|

– check finance |

|

|

|

– draw transfer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– stamp documents |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– [prepare mortgage] |

|

|

|

– register dealing |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

82

CONVEYANCING

(1)UNREGISTERED CONVEYANCING

(a)Pre-contract

A contract for the sale of land has to be made by signed writing, so neither side is committed until there is an exchange of contracts. The contract is prepared in duplicate. Each side signs one copy, and, when both are ready, they physically exchange parts.

The vendor’s solicitor begins the process by obtaining the title deeds. If the property is in mortgage, he probably borrows them from his client’s bank or building society against his own undertaking (his personal promise as a professional lawyer) to pay off the mortgage out of the proceeds of sale. He peruses the deeds to determine what exactly his client has to sell, and draws the contract accordingly. He probably uses a standard form contract or otherwise incorporates a set of standard clauses (‘general conditions’) tailoring them to the needs of the particular transaction (‘special conditions’). He sends the contract to the purchaser’s solicitor for approval.

The general principle is caveat emptor (let the buyer beware), and so the purchaser’s solicitor will try to discover whether there are any skeletons in the vendor’s cupboard before he commits his client. First, he will make a local search. The local authority (district council or London borough) maintains a register of local land charges, containing details of various incumbrances affecting properties in its district. They are mostly public charges: items like charges for street works or sewers, the conditions attached to planning permissions, smoke control zones, tree preservation orders, compulsory purchase orders. The purchaser needs to check the local land charges register. He does that by sending the prescribed form to the local authority and paying a fee. At the same time, he sends another standard form containing additional inquiries, hoping to elicit any further information the local authority may have about the property: Are the roads adopted? Is the property connected to a public sewer? Does the council know of any other actual or potential events which may adversely affect the purchaser? The expression ‘local search’ implies both the official search and the additional inquiries.

83

UNDERSTANDING LAND LAW

Some councils can take weeks to reply and, in order to save time, it may happen that the vendor’s solicitor will make a local search even before a purchaser is found, so that the result of the search is available to be sent out with the draft contract.

The second step which the purchaser’s solicitor will take is to obtain from the vendor’s solicitor replies to certain preliminary enquiries. The vendor is not under a general duty to disclose any information to the purchaser unasked, but the purchaser’s solicitor will invariably seek at least the answers to a standard set of questions: Are there any boundary disputes? Has the vendor duly observed any restrictions affecting the property? What fixtures and fittings will be left in the property, and what taken? And so on. These days, in order to save time, the vendor’s solicitor often sends out with the draft contract his replies to the standard form enquiries – without waiting to be asked.

The third thing a purchaser’s solicitor will do is to ensure that his client has sufficient financial resources to see the purchase through. That usually means waiting for a formal, written offer of a mortgage loan by a bank or building society.

Assuming he is satisfied on all three scores, the purchaser’s solicitor is ready to proceed – or almost. The bugbear of conveyancing is the chain transaction. When people move house, they generally expect to use the sale price from the old house to finance the purchase of the new. Therefore, the typical buyer is unwilling to exchange contracts to buy on the one hand unless and until he is ready to exchange contracts to sell on the other; by the same token, the typical seller is unwilling to exchange contracts to sell on the one hand unless and until he is ready to exchange contracts to buy on the other. This phenomenon is called ‘tie in’, and results in a, sometimes lengthy, chain of transactions. At one end is a first time buyer or someone who is not dependent on a sale. At the other is someone who is not waiting to buy another house. In between, everybody is waiting for those above or below them in the ladder. Eventually, when all are ready, all exchange – all (usually) on the same day.

At that point, the contract becomes binding. It is customary for the purchaser to pay over a deposit of 10% of the purchase price upon exchange of contracts.

84

CONVEYANCING

(b)Post-contract

Contracts exchanged, the vendor’s solicitor deduces title. The contract has stipulated the nature of the title on offer, and it is for the vendor now to prove that he can convey a good title to the land. In days gone by, title was deduced by sending an Abstract of Title – a typewritten summary of the essence of the title deeds, set out in a traditional pattern. Today, the vendor probably sends photocopies of the relevant deeds (perhaps listed in an Epitome of Title). The purchaser’s solicitor examines the title and raises requisitions – he sends a list of any objections he may have to the title offered, perhaps asking the vendor’s solicitor for evidence of this event, or seeking further information about that. He also draws the draft conveyance and sends it to the vendor’s solicitor for approval.

Meanwhile, if the purchaser is borrowing some of the purchase price, work will be proceeding on drawing up the mortgage deed, formally reporting to the lender that the title is a good and marketable one, and requisitioning the money in time for completion. Many banks and building societies instruct the purchaser’s solicitor to act for them too, so as to save costs, but some lenders insist on instructing their own lawyers.

Shortly before the day fixed for completion, the purchaser’s solicitor will send a search form to the Land Charges Registry designed to check that there are no unexpected land charges registered in respect of the property. The purchaser will take the legal title on completion, and so the issue whether he is a BFP (remembering that notice, in this context, means registration) is to be judged as at the date of completion.

If the purchaser is borrowing some of the purchase price, a search will also be made at the Land Charges Registry against his name to check that no bankruptcy proceedings have been commenced against him.

The reply from the Land Charges Registry is in the form of an official certificate which gives details of any relevant entries. It carries a priority period of up to 15 working days. That means that the purchaser is not affected by anything registered between the date of search and the date of completion, provided he completes within (approximately) three calendar weeks of the date of the search.

If all is in order, completion takes place. The purchaser’s solicitor pays over the purchase moneys (usually ‘down the wire’ by electronic transfer of funds from his bank to the vendor’s solicitor’s bank), collects the deeds (probably by post) and completes the mortgage, if any. The purchaser is now the legal owner of the house, and may move in.

85

UNDERSTANDING LAND LAW

(c)Post-completion

After completion, the vendor’s solicitor has only to tidy up the loose ends. He must redeem the vendor’s mortgage out of the proceeds of sale if he gave an undertaking to that effect. In any event, he reports completion and settles his account with the vendor.

The purchaser’s solicitor, on the other hand, still has much work to do. He must have the conveyance duly stamped and pay any stamp duty levied on it. Then he must convert the title from unregistered to registered by sending in the appropriate application form to the Land Registry. The application should be submitted within two months of completion.

(2)REGISTERED CONVEYANCING

(a)Pre-contract

The comparative simplicity of registered conveyancing becomes apparent at the very beginning of the conveyancing process. The vendor’s solicitor finds it much easier to draw the draft contract. He will doubtless requisition the Land or Charge Certificate from the vendor or his mortgagee, as he would requisition the title deeds for unregistered land, but he also applies to the Land Registry for office copy entries of the vendor’s title. These give him a clear and authoritative report on the current state of the title; he does not have to ferret through several deeds to find out. The actual drafting of the contract is easier too. The vendor’s solicitor simply describes the property by reference to the office copies, and sends the office copies out with the contract.

For the purchaser’s solicitor, the pre-contract stage is not very different. He still obtains his local search; he still makes his preliminary inquiries of the vendor, and he still awaits a mortgage offer. And the problem of tying in sale or purchase or both may still arise.

86

CONVEYANCING

(b)Post-contract

After contract, the vendor’s solicitor theoretically deduces title to the purchaser’s solicitor, but it is an empty obligation: the title consists of the office copy entries, and they were supplied with the contract. The purchaser’s solicitor raises his requisitions, but they are of a formal nature. There cannot be anything of great moment, for the title is guaranteed by the State. Moreover, the purchaser’s solicitor saw the title before contract, and if there had been anything untoward he would have delayed exchange of contracts until he was satisfied.

Drawing the transfer document is scarcely an onerous task. It is just a question of taking the appropriate Land Registry form and filling in the blanks. Mortgage arrangements (if any) do not differ very much from unregistered to registered conveyancing – save that the examination of title on behalf of the lender is simplified.

The final searches, however, are different. The purchaser’s solicitor sends his search to the Land Registry. The application states the date of issue of the office copies supplied by the vendor’s solicitor and asks whether there has been any entry on the register since that date. Armed with the office copies and an official certificate setting out the result of his search, the purchaser’s solicitor knows exactly what is the current state of the title. The official search carries a priority period of 30 working days. But

– and this is the major difference – the purchaser needs not only to complete his purchase within the 30 days, he also needs within those 30 days to lodge at the Land Registry an application to register his purchase. The reason is that, whereas in the case of unregistered conveyancing the purchaser acquires the legal title on completion of the deed of conveyance, nevertheless in registered conveyancing he does not acquire the legal title until his name is entered on the land register. His registration as the new proprietor will be backdated to the date upon which his application was received at the Land Registry, but until he lodges his application, his interest in the registered land ranks only as a minor interest and is, therefore, vulnerable.

If the purchaser is borrowing money, a search will be made against his name at the Land Charges Registry to check for possible bankruptcy, but there is no point in doing a bankruptcy search against the vendor there. The purchaser of registered land takes the title as registered, and if there is no inhibition or other relevant entry at the Land Registry, then that is an end of the matter.

Otherwise, completion will follow the same procedure as in an unregistered transaction.

87

UNDERSTANDING LAND LAW

(c)Post-completion

After completion, the vendor’s solicitor tidies up the loose ends, as in the case of an unregistered transaction, and the purchaser’s solicitor also has the same sort of chores to perform. There are, however, two significant differences for him. First, an application to register dealings is more straightforward than an application for first registration. Second, he must be sure to get his application to the Land Registry before the expiry of the priority period of his search.

88