Tachjian V., Reconstructing Armenian Village Life Manoog Dzeron and Alevor

.pdf

legacy that drove Manoog Dzeron to sketch these implements of rural life in complete detail. Certainly, he would not have done this had he continued to live a normal life in Parchanj or had the Catastrophe, which uprooted every facet of an Armenian existence from this village, not occurred. hus, the Turks of Parchanj, who were Manoog Dzeron’s contemporaries and continued to live there, most likely used the same tools to plough the land, harvest grapes, or mill wheat, and didn’t use such remember-writing and remember-sketching methods.

he pain of loss, longing, and demand for justice were all emotions that Manoog Dzeron experienced when preparing his book. hese were the main motivators behind his memory writing and memory-sketching project. Absent such emotions, he most likely would not have initiated such a work, complete with text and drawings, to reconstruct a past life, especially not with such diligence and vigor. here are 116 drawings in the Parchanj book. he author has sketched a wheel cart with all its component parts, all the tools used for weaving, the flaxseed oil press, the factory making silk from cocoons, the process of combing cotton, and many others.

We find 166 drawings in Alevor’s book. hough less than perfect, they nonetheless are very helpful from the perspective of resurrecting a material culture. In this series, for example, is the khorbologh (also, khulinchak or khulunchik), which was hung from the very center of the house ceiling throughout Metz Pahk (Great Lent). It is was constructed of a firm onion with seven rooster feathers pressed into it, each one representing the seven weeks of Great Lent. his sketch by Alevor of the Palu khorbologh is unique in the fact that we also see a small spear attached; a symbol used to frighten any children thinking about violating Lent.

heir books of the two authors are replete with dialect words, many of which have fallen out of use or their meaning forgotten with the passage of time. Alevor’s dictionary includes some 3,500 words; and that of Manoog Dzeron’s, 1,700.

To remember the past, but to also present the social milieu and its contradictions

he books of Manoog Dzeron and Alevor were written with the aim of presenting the village life of Parchanj and Palu, respectively. Alevor does not directly focus on his native village of Trkhe; in fact, it is hardly even mentioned in his book. For him, the Armenian-populated village of Palu and Armenian village life comprise one overall subject. For this reason, his descriptions cover all of the regional villages. As for Manoog Dzeron’s book, its general subject is restricted to Parchanj, or more correctly, the Armenians of Parchanj. he exception is the subchapter entitled, “he Turks of Parchanj,” that includes various sections: “Turkish families,” “Memorable village Turks,” “he religious and educational state of Turks,” “he Turkish family: Customs,” “Turkish traditions: Betrothal, wedding, divorce, hac/hadj (pilgrimage),” “Community

223

Armenian family photos from Parchanj published in Manoog Dzeron’s book.

administrative structure.”28 Despite Dzeron’s inclination to paint Turks in a negative light, the information is nevertheless of merit, especially when we use it to understand how the Armenian, in this case Manoog Dzeron, portrays the Other.

he Other—the Turk and the Kurd—is never a separate subject of discussion in the remaining pages of the Parchanj book, nor in the work by Alevor. he aim of both authors is purely the re-establishment of Armenian memory and heritage. Other authors writing books in the memory genre in the post-genocide period also pursued this objective. hey bear the stamp of the times, and follow the dictates of the spirit of the period. Here, the Other is overlooked and has no separate place in local memory. And if recalled, it is usually assigned a negative character, one of the causes of the tragedy Armenians experienced.

Butthis,too,isjustonefaceofreality.hus,whenwedelvedeeperintoastudyofthebooks by Manoog Dzeron and Alevor, it is not di cult to make out that the Other is implicitly

28 Dzeron, pp. 23-30.

224

present and is an integral part of the Armenian social fabric. he Other not only symbolizes violence and the final Catastrophe; the centuries-old coexistence between it and the Armenian also includes a number of grey zones. hese appear unavoidably in simple descriptions, when the two authors write about daily life, farming, crats, and commerce. Such short and specific bits of information are numerous and are the means to not only re-establish the daily life of Palu and Parchanj Armenians, but also to more closely study the existing socio-economic structure and the roles played by various groups operating there.

hus, for example, in order to understand the living conditions of the villager in the Harput-Palu region, it is important to appreciate the type of local rule that reigned there. Here, we are assisted by Manoog Dzeron and Alevor, the information of one supplementing the other. he Ottoman state system was extremely weak in this region and the absence of a central authority was the major source of general insecurity. What ruled instead was the power of local Turkish and Kurdish beys and aghas. hey owned most of the fields, gardens, and pastures. A majority of the Armenian and Kurdish villagers were connected to them through what was called a maraba status, in that the land they farmed belonged to the aghas and beys. As we shall see, the villagers received only a tiny fraction of the harvest. he maraba was quite burdensome. During the Tanzimat period, many Armenians were able to free themselves from the status, but in successive years the beys and aghas gradually regained control of their former lands. In 1908, ater the declaration of the Ottoman Constitution, Armenians once again attempted to wrest free from the maraba status, and many did. According to Manoog Dzeron, some three-quarters of the Armenians of Parchanj became the owners of their land. But in conditions of poverty, the maraba status could become a source of relative security. A bey or agha would provide their marabas with seed only. Village farmers had to perform the rest of the work, including various services to their masters. But the same bey or agha would also defend their marabas from violence and pillage. hus, as Manoog Dzeron writes, Armenian villagers would compete amongst themselves to become the maraba of this or that bey. It was only the improvement in Armenians’ political conditions, which took place temporarily ater 1908, that a orded a way out of maraba status. Otherwise, local solutions were rare. For this reason, there was a mass migration of menfolk from the Palu and Harput regions to Adana or Istanbul, and later towards the United States.29

Within this general system, the common Kurdish villager occupies an interesting place. According to Alevor’s book, the Kurdish peasant belonged to a group of local beys or aghas who exploited the Kurds even more than they did Armenians. he Kurdish peasant was the poorest of the poor in the Palu district. So extreme was their situation that they were to be found on the outskirts of Armenian villages, either to beg or to burglarize. In

29 Ibid., pp. 109, 141, 188-189, 232-234.

fact, the Kurds were oten guilty of stealing grapevines from Armenian gardens. hese same, poor Kurds would return to the villages ater the cotton or grain harvest to beg for some cotton or wheat from the Armenian peasants.30 het was a constant scourge in the daily life of the Armenian villager. here is ample, and interesting, information about this theme and the identity of the thieves in the works of both authors. Alevor reveals that Kurds also worked as gardeners (baghbanji) of the gardens belonging to Armenians in the Palu villages. his was perhaps a wise move on the part of the Armenians, as it likely prevented the thet of vine stock.31 An architectural detail of the rural houses of Palu and Harput also has much to say about this problem. In Armenian homes, the cowshed, stable, and haylot were all to be together within the walls of the house. Local Kurds, on the other hand, built their cowsheds and stables several minutes walking distance from their house. his di erence, Alevor notes, stems from the Armenians’ fear that their livestock would be stolen, something that rarely happened to the Kurds.32 Equally expressive are the written magical enchantments (apson, in the local dialect) that were made in Parchanj to ward o the evil eye, illness, and attacks from dangerous animals and malevolent spirits. hese spells were written in Armenian. here were also some anti-thet spells that, while recorded in Armenian, also included excerpts in Turkish. he weavers of these magic spells were aware that the thieves were generally not Armenian.33

The ‘One-Tenth’ tax system: The weakening of the state system and the strengthening of ‘agha’/‘bey’ local rule

When describing the cultivation of wheat, cotton, and grape vines, Alevor speaks at length about the “one-tenth”34 system (tithe) and its collection methods. hese passages are very useful in gaining a better understanding of the various nuances in the tripartite Armenian villager–agha/bey–state relationship.

he method in which this government tax was collected reveals the power of the beys and aghas. he state was not directly involved in collecting the “one-tenth” tax. Alevor points to the expense in sending government o cials to far-flung rural regions as the reason. Instead, the government found it more convenient to put the villages’ tithes up for auction and sell them to local wealthy individuals. he Ottoman co ers thus received the cash value of the tithe tax in advance, with the buyer having to collect the actual tax

30Alevor, pp. 46, 148.

31Ibid., p. 154.

32Ibid., p. 253.

33Dzeron, pp. 130-131.

34Aşar is the main source of income for the Ottoman treasury. Levied on agricultural production.

226

in kind, store it, transport it, and finally sell it himself. he auction would take place in the Palu government o ce courtyard when the crops were just ripening. he auction date was o cially announced in advance. he wealthy individuals who wanted to bid for the tithe would gather in the courtyard, along with members of the kaymakam’s governing council (irade meclisi), which included the Armenian prelate of Palu and two other Armenian members. he town crier (munetik) would then announce the name of the first village, pointing out that its tithe was up for sale, and call for bids. he bids would rise until only one or two bidders were let. he remaining bidder(s) would have to provide guarantees to the o cial body present. Only ater doing so would they sign the auction’s bill of sale. he tithe thus belonged to the buyer, and the government remained removed from subsequent related activities.35 Government bodies would only intervene when the collector was in dispute with the villagers; in these cases, police intervention would usually be in favor of the tithe buyer.36

In Palu, the tithe buyers were always the same three or four people—the local influential beys. Since they were always the ones participating in the auction, uno cially, the collection of the tax became their “right.” No one else dared to take part in the bidding, certain that the same beys would regard it as a trampling of their privileges, and that

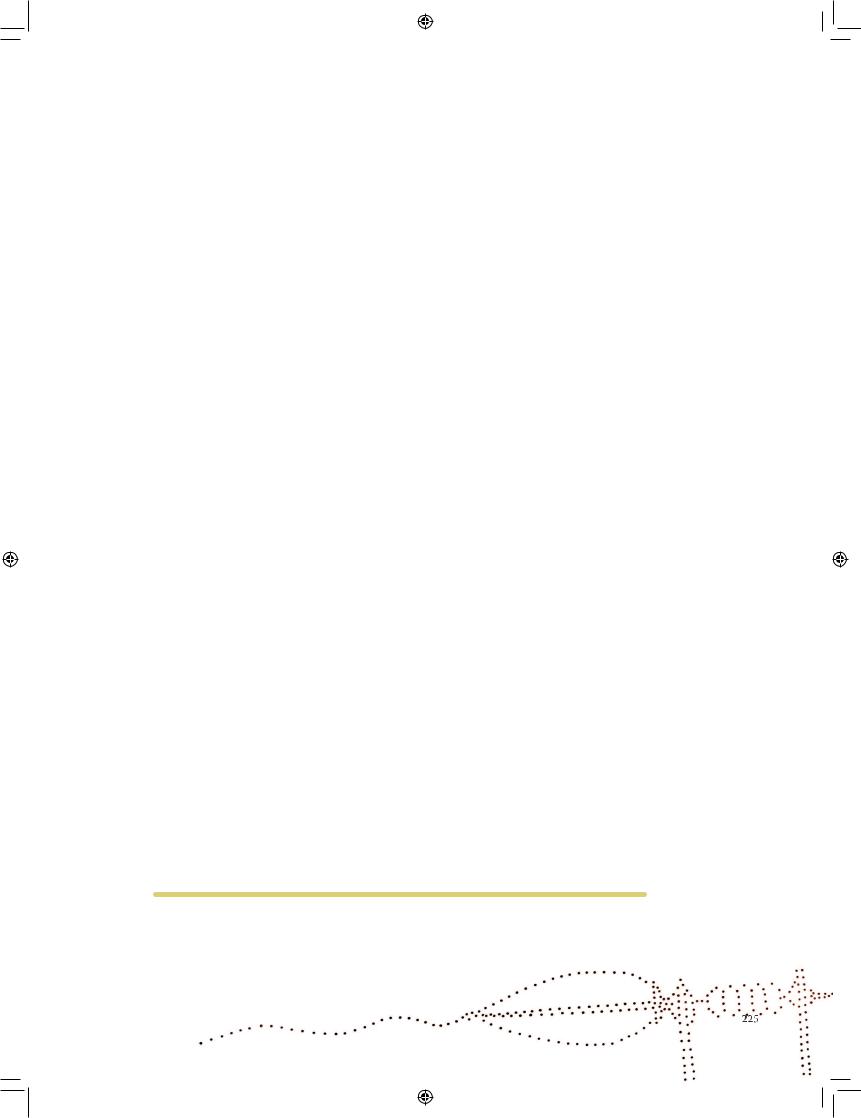

A workshop in Parchanj village belonging to Kelen Arut, where silk is recovered from cocoons:

1 | copper tray

2 | cocoon

3 | hearth

4 | bench

5 | cupboard

6 | get-gal

7 | reel

8 | hook

9 | whip

10 | top

11 | main reel

12 | string

Drawn by Manoog B. Dzeron, redrawn by Levon M. Dzeron in 1933

35Dzeron, pp. 159-160.

36Ibid., p. 105.

227

repercussions would be inevitable. In such circumstances, when there was an absence of fierce competition, the auction bids would not rise, and the entire operation would be considered a loss for the Ottoman treasury. Clearly, the main beneficiaries of such a situation were the beys. Alevor gives an example of a village where the tithe was usually sold for 6,000 ghurush/kuruş every year. When the beys were not able to attend an auction, the tithe would be raised to 30,000 ghurush.37

Alevor also goes into great detail about how the tithe was collected. he tithe holder would not go to the villages himself, but would send his representative, a person called a shayna or shahna (likely the Turkish word şahne), to collect them. he person who carried out these functions was also known as a mültezim (contractor) or aşarci. In his book, Alevor records the entire ceremonial procedure—that is, how the shayna was received with great hospitality in the villages, how he would measure the wheat and other cereals taken to the threshing floor, how he would travel to the gardens and cotton fields to measure the amount of the overall harvest, how he would be bribed, and how disagreements would be settled.

Half of harvest measured by the shayna had to be handed over by the maraba villagers to the landowner—the Kurdish bey or agha. he tithe was taken from the remaining half. Alevor notes how one should not accept the amount of “one-tenth” (the tithe) at face value. It was more, and usually represented one-eighth, or 11.76 percent. According to the same author, there were also circumstances where the “one tenth” has been represented as one-seventh, or 14.28 percent of the remaining harvest. Next in line were the creditors, who were usually cratsmen—blacksmiths, cobblers, and painters— from the same village who had done some type of work for the farming villager during the year. hey would be waiting for this special day in the life of the village to receive payment in kind—a portion of the remaining grain. What finally passed into the hands of the villager is what was let ater all of this.38

Armenian village schools: The fruit of communal governance and cooperation

If the weakness of the state system and absence of governmental bodies could, on the one hand, open the door to a number of security issues, it could also, on the other hand, be the reason why Armenian villagers of Palu and Harput sought to independently organize communal life. he school system and its development is a case in point. Here, the arrival of Western missionaries spurred the establishment of modern schools in the Harput valley. he American missionaries operating in the Harput region opened the first modern educational centers. Education and the proselytization of Protestant or

37Ibid., p. 105.

38Ibid., p. 109.

228

Catholic beliefs went hand in hand at these institutions. At the same time, however, the educational work carried out by the missionaries irrefutably imparted a new vibrancy in the provinces and created an atmosphere of competition that must, nevertheless, be regarded as positive and productive.

he establishment of missionary schools, coupled with the adaptation of new teaching methods and the quick development of education for the girls in those institutions, surely created a powerful psychological and lifestyle shock to the rural milieu. Of course, the majority of Harput area Armenians, belonging to the Armenian Apostolic Church, would have preferred to have their own institutions. In terms of financial resources, the competition was on an unequal footing. Nevertheless, it is clear that community leaders could not take a passive approach to this issue.

he opening of missionary schools, especially when Muslim boys and girls started attending them, also caused a degree of panic among the Ottoman authorities. Since

Harvest time in the plain of Harput/Kharberd. Photograph by Askanaz Sursurian.

Marderos Deranian archives, NAASR, Belmont, MA.

229

it was impossible to halt the activities of the missionaries through legal channels, the only option remaining was to establish a government directory of educational institutions.39

he development of a dynamic and powerful missionary educational network truly became a call to arms and action directed at the Ottoman state and community (millet) bodies.Startingfromthesecondhalfofthe19th century,stateandcommunityinstitutions began working to increase the number of government and community schools. But the example of the Harput region clearly shows the extent to which community structures, as compared to those of the government, were more dedicated to and proficient in the educational tasks they initiated. he quick growth and development of educational institutions belonging to the Armenian Apostolic community in the Harput valley, in the span of a few decades, was primarily the result of a spirit of organization, of inner communal cooperation and support.

Manoog Dzeron was very familiar with the Turkish school established in Parchanj, especially since it was located quite close to his home. He also attended it for three days. Only boys could enroll in this institution, and there was no corresponding girls’ school. Dzeron’s description of the conditions at the school was quite negative. We do not know whether the school improved ater Manoog Dzeron let Parchanj, but we do not believe it could have equaled the Armenian schools (Protestant and Apostolic) that had been placed on a solid footing beginning in the mid-19th century. In 1870, the Parchanj Apostolic community laid the foundation for the Krtasirats Society, which was tasked with supporting the boys’ school that had opened in 1845. In 1888, through the e orts of Krtasirats, the school moved to a new building and became co-ed.40 A Protestant school, with a standard curriculum, opened its doors in the same village in 1873. All of the students were Armenian. In the mid-1890’s, the Protestant school moved to a new building and also began accepting girl students.41 Parchanj residents who had immigrated to the United States contributed significantly to cover the financial costs of the Apostolic community school. In 1891, they established the Perchenj Gyughi Lusavortchakan Dbrotsasirats Enkerutyun (Perchenj Village Apostolic School Supporters Society) in the Massachusetts town of Fels. All of its members worked in the Boston Rubber Factory. Branches were quickly set up in towns throughout the United States—in Worcester, Whitinsville, Cambridge, Charlestown, Malden, Salem-Peabody, Stoneham, and Lawrence-Lowell, Mass.; in Hartford, New Britain, Madison, Naugatucket, Conn.; and in the state of California. By 1902, these branches,

ş The Modernization of Public Education in the Ottoman Empire, 1839-1908

39 Selçuk Ak in Somel, Imperial Classroom. Islam, the State, and Education in(Leiden/Bosthe Late Ottomann/Köln:EmpireBrill, 2001) pp. 42-43, 202-204; Benjamin C. Fortna,

(Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2002) pp. 50-60.

40Dzeron, pp. 177-178.

41Ibid., pp. 178-179.

230

combined, had a membership of about 100.42 During the 1912-1913 school year, the Parchanj boys’ school had six classes with 82 students, and the girls’ school had four classes with 32 students.43

his, then, is an example of communal cooperation, of villagers banding together totally independent of the state system. he educational life of Parchanj Armenians greatly benefited from such collaborative e ort.

Conclusion

Let us now take a look at the overall state of the Armenian diaspora when the books by Manoog Dzeron and Alevor were written. During the 1920’s and 1930’s, a politicized atmosphere reigned throughout the diaspora. Ideological conflicts had led to divisions within the larger Armenian communities of the United States, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Greece, Argentina, and France. he main reason for the intra-communal splits was the issue of Soviet Armenia, as well as the classic inter-party struggles and their e ects on diasporan community structures. hese were also years when Armenian compatriotic unions still played an influential role in Armenian political and cultural life. hese societies also played their part in inter-community struggles. When we present the issue schematically, we see the ARF and the organizations supporting it on one side of the dividing line, and the Hentchak and Ramkavar parties, along with the AGBU, on the other. he first group assumed an uncompromising stance against the Communist regime in Armenia and fought for the restoration of the First Republic. he second group attempted to overlook its ideological di erences with the Communists and viewed cooperation with the Soviet authorities as of primary importance, in the name of the development and strengthening of Armenia. he elements comprising the Armenian diaspora were mostly of an exile background. he partisan-ideological environment of intolerance and incompatibility sometimes led to violence and even death.

In such tense conditions, divisions surfaced within various compatriotic unions, to the extent that two compatriotic unions, representing the same historic town or village, operated in opposition to one another in the same diasporan community. It was during this period when the first houshamadyan books appeared. It was not a rare occurrence for the partisan-ideological struggle to lead to more than one work being written regarding a former Armenian village, town, or region of the Ottoman Empire. Given the political atmosphere of the day, these books were regarded as opposing one another. One can rightly ask how it is possible to observe internal Armenian contradictions in books written about the memories of one Ottoman town or village. Interestingly, such divisions generally surfaced in a section that appeared in almost all of the memory

42Ibid., p. 181.

43Ibid., pp. 177-178.

231

works—that dealing with “political life,” “the political parties,” or “revolutionary/fedayi activities.” As dictated by conditions dominant in the diaspora, the authors of other such memoirs perhaps overvalued the importance of these chapters and devoted copious pages to them. Of course, the influence of post-genocide Armenian historiography had a role in this, as attempt were made to henceforth portray the centuries-old history of Ottoman-Armenians solely through images of violence, massacre, and resistance to despotism. he organizers of this resistance were the same political parties that continued to operate in the diaspora. hus, if the author of a certain memoir didn’t portray a certain party “properly” in the aforementioned chapters, the aggravated party would launch the publication of an “accurate” accounting, which depicted it in a more fitting manner. It is certainly due to these contradictions that various locales (Harput town, Hussenig, Bardizag (Partizak), Van, Musa Ler, Tomarza, Havav, Zeytun, Taron region, and others) have two or more memory books.

Manoog Dzeron and Alevor seem to have steered clear of such dominant political factors. “Politicized” chapters are simply absent in their books, which is a rare occurrence in the memory genre. It is not as if the two authors were removed from political life. Until his death, Manoog Dzeron was an active member of the Ramkavar-Azatakan Party in the United States.44 As we have seen, in his “Last Words” he writes that he regards his work as a faraghat (property deed) directed to future generations. In the sentence that follows, the reader perceives the pressure of a political stance: “In order that hey [the next generations]—when they grow up, multiply, and get stronger in the New Parchanj blossoming on the sunlit slope of Ararat—one day...with this faraghat, in their hands as a compass of inspiration, they will return to the home of our forefathers, that they will nd, reacquire, and rebuild Mother Parchanj [emphasis his].”45 his political stance is expressed not only in the form of demands from Turkey, but also in a sympathetic position regarding Soviet Armenia. Elsewhere, Dzeron writes that he has three dreams (muraz): he first is the publication of his book; the second, the establishment of New Parchanj in a resurrected Soviet Armenia; and the third, to visit Armenia and New Parchanj with his wife.46

For many years, Alevor served in the important capacity of locums tenens of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Egypt, where an Armenian community was experiencing the upheavals of political conflicts. He died during such a period of upheaval caused by the immigration movement to Soviet Armenia. housands of Armenians were preparing to relocate to Armenia, and the immigration assumed political overtones. Egyptian-Armenian newspapers were extensively and continually covering the issue.

44Manuk K. Jizmejian, [Kharberd yev ir zavaknere] [Kharberd and its children] (Fresno, 1955) p.

45Dzeron, p. 251.

46Ibid., p. 62.

232