Tachjian V., Reconstructing Armenian Village Life Manoog Dzeron and Alevor

.pdf

released. Harutyun and Poghos continued to pursue the relocation plan, but this time the o cial barriers proved insurmountable. Given these conditions, the Pazarcık plan was scrapped. None of the Armenian villagers were compensated for the huge expenses they had incurred.11

Manoog Dzeron went back to his job as an assistant engineer. he vali of Mezire, taking into account the young man’s four years of satisfactory service as an architect, sent a letter to Istanbul, proposing that he be given a higher level post. But in 1889, an order was received from Istanbul to expel all Armenians from the architectural and engineering state institutions. Manoog Dzeron consequently decided to leave the Ottoman Empire, and arrived in the United States in 1890, settling in Worcester, Mass. He then moved to Chicago and later Joliet, Ill. In 1893, he was joined by his wife and daughter Nvard. Six sons and one daughter were born to the family in the States. Manoog Dzeron died in 1938.12

his short biography shows that we are dealing with an Armenian who was very familiar with the contradictions and extremes of the Ottoman regime, someone who was also a prominent architect who knew his village and its life well.

Alevor: A village priest, or A man very familiar with the rural life of the Palu and Harput regions

Biographical data on Father Harutyun Sargisian is quite scant. He was born in 1864 in the provincial village of Trkhe (present-day Keklikdere) in Palu. He attended the local school and in 1875 traveled to Istanbul with his father, where he enrolled in the Samatya Sahakian School. In 1877, he returned to his village and then enrolled in the Harput Surb Hakob School administered by Tlkatintsi. He was ordained a priest in Urfa in 1894, and the following year was assigned to the village of Sarıkamış, in the Harput Diocese. From 1896-1901, he resided in the town of Harput, serving as a priest in the Surb Hakob neighborhood. He taught religion in the parish school in the same neighborhood, while simultaneously attending Armenian-language and science courses. From 1901-1902, he served as a priest in the Harput village of Kesirik (present-day Kızılay), and from 1903-1907 in Erganimaden/Arghana Maden (present-day Maden). Here, under his initiative, the Armenian school where he also taught was renovated. In 1908, he has moved to Adana and later, to Mersin. In 1909, he traveled to Egypt, intending to depart to the United States. But, he stayed in Cairo, teaching theology and church history at the local Galustian School. He served as the Locum Tenens from 1911-1914, and again

11Ibid., pp. 233-234.

12Ibid., p. 59.

213

from 1916-1934. For a time, he was the clergyman who tended to the Armenians in Egyptian jails. He let a great many articles on religious themes, written under a variety of pen names; for example, Paylak (in the “Luys” newspaper, Istanbul), Chambord (“Byuzandion” newspaper, Istanbul), Norek vshtakir (“Lusaber” newspaper, Cairo), Aratzani (“Sion” monthly, Jerusalem, as well as “Haratch” newspaper, Paris) and of course Alevor (“Lusardzak” weekly, Cairo). He died in Cairo on July 24, 1947.13

Like Dzeron, Alevor also let his native village quite early on. Yet, his memories of his birthplace did not wane; on the contrary, as the clergyman from Trkhe wrote, “ater the tragic collapse of my centuries-old native village, its apparition began to live even stronger in my imagination…”14 Prior to his short stay in Cilicia and his later permanent resettlement in Egypt, Alevor spent half his life in a village setting. Trkhe, Sarıkamış, Kesirik, Arghana Maden—these were all villages where Alevor worked as a parish priest and teacher, but also, we believe, as an average villager doing various household and agricultural chores.

Agriculture, crafts, holidays, traditions, families: Restoring daily life

A sincere reproduction of village life comprises the core of the books written by Manoog Dzeron and Alevor. he two authors tried their best to achieve this. Before appearing in book form, Alevor’s work was published in serial form in the Cairo weekly newspaper Lusardzak from 1927-1928. he series was interrupted when the newspaper closed. In 1930, Alevor had the opportunity to spend a week in Beirut and Damascus, where he culled information from former Palu residents and other compatriots now living there, which he published in a separate work in 1932.15 Alevor’s book was an exception, in that many books in the houshamadyan genre were a result of collaborative work. It was the compatriotic union of former village residents living in the United Sates that raised the funds and placed the order for Manoog Dzeron’s Parchanj book. While Dzeron’s personal stamp is evident on every page of the book, he nevertheless collected certain information from his compatriots. Manoog Dzeron wrote the book from 1931-1937.

At first glance, one finds many similarities in the descriptions given by the two authors. his is to be expected, given that Harput and Palu are located in the same geographical zone, and there aren’t major di erences in traditions, dialect, traditional farming methods, dress, house building, home chores, and other aspects of daily life. hus, a natural closeness is created between these two books and, regarding various themes, they complement one another.

13Ardashes H. Kardashian, , . . [Nyuter Yegiptosi Hayots Patmutyan hamar, Vol. 1] [Material for the History of Egypt Armenians, Vol. 1] (Cairo, 1943) pp. 210-211; Alevor, p. A., 272.

14Alevor, p. b.

15Ibid., p. a. Elsewhere in the book, Alevor writes that he was in Beirut in 1933 (ibid., p. 333).

214

he two authors describe village life in a completely natural way, for both are children of the village. In the case of Alevor, it is clear that he also tilled the land and personally used many of the farming and household tools he describes. Manoog Dzeron, on the other hand, was a master mechanic and architect, and it is clear that he enjoyed providing descriptions and instructions on the building of village homes and watermills, and the use of engineering equipment. Examples can better show that this was the case.

One of Alevor’s masterpieces is his description of the cotton-making process, from harvesting the crop to producing yarn. He was very familiar with this cultivation and crat, and his depiction is based on personal experience. he chapter on farming starts with the process of preparing cotton seed for sowing, and then portrays the sowing itself, followed by the kakhank, the work to clear the fields of harmful and unnecessary grasses. he next step is the bampak krtel, where the upper portion of the cotton stalk is slightly cut to allow the plant to grow and produce branches. hen, the cotton enkuyz (unopened cotton bud) blossoms, quickly turning into a khchech (opened bolls). he field work ends with the harvest (kagh) of the buds. he crop is brought home, where it undergoes a number of stages in the handicrat process. For the Armenians of the Palu district and the Harput valley, this was surely a skill passed down through the centuries. he first stage, called tchalkhavu, allowed for the separation of the cotton from the entwined vines, leaves, soil, and dust. he cleaned opened bolls were then separated, one by one, from their dry and sharp husks. Another machine called the

Threshing of harvested wheat in Harput/Kharberd plain.

Marderos Deranian archives, NAASR, Belmont, Mass.

215

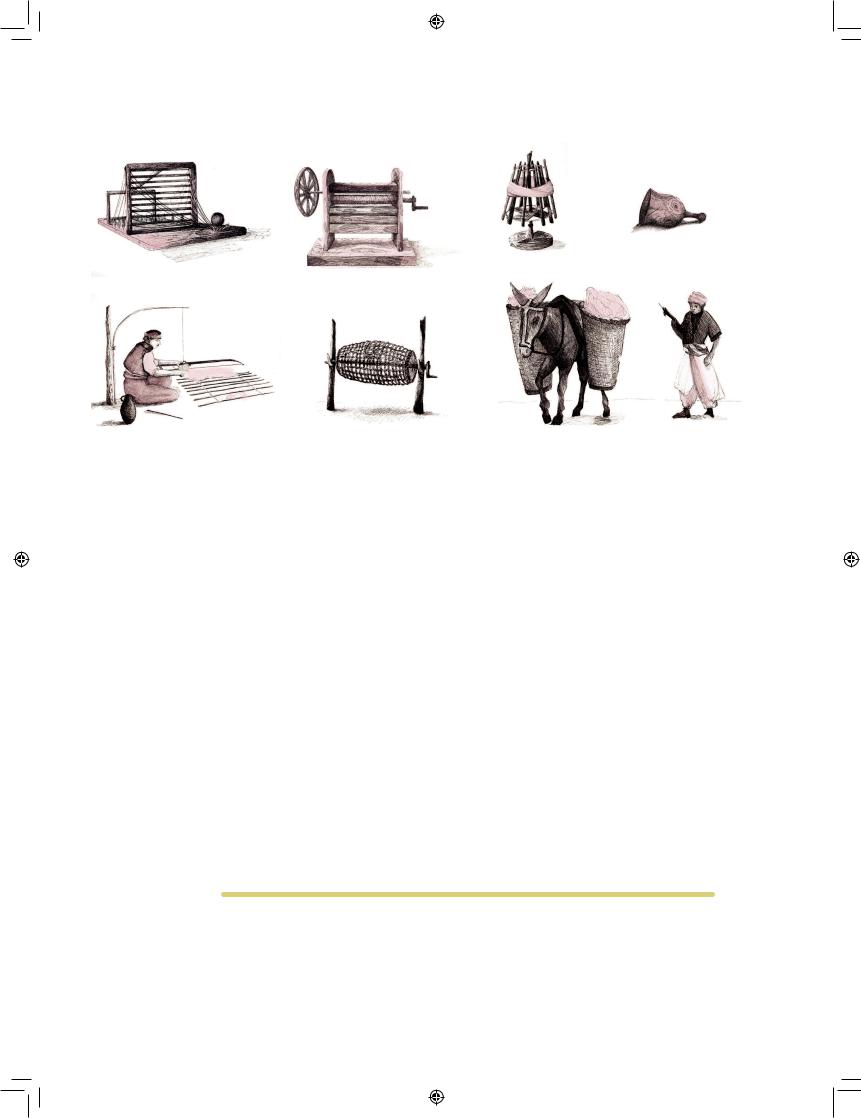

Agricultural and household items used by Armenians living in the plains of Harput/Kharberd and Palu.

chrchr was then used to separate the cotton from the husk. he next step was to card/ comb (aghnel) the cotton, sotening and cleaning the fibers. his was followed by using a spinning wheel (jayr) and an implement called a nazuk to turn the fibers into a spun yard twisted onto a masura. hese implements were then placed on a tastachagh, the henk (warp; in weaving cloth, the warp is the set of lengthwise yarns that are held in tension on a frame or loom) was prepared, and it was then possible to begin the hor (wet; thread or yarn that is drawn through the warp yarns) work, the actual weaving of the cloth. Alevor devoted 24 pages to describing the entire process in painstaking detail, resurrecting this ancient weaving crat, the Palu variation of which no longer exists today.16 For the average, non-expert reader, all of this might seem somewhat burdensome or tedious. Even experts may not understand certain descriptive segments. We have the impression that Alevor wrote quickly, not reviewing or editing his text. Yet, there is a rich vocabulary regarding weaving and agriculture, in general, to be found in these pages. Many of the words are no longer used today; the meaning of some cannot even be found in the most specialized of dictionaries. Nonetheless, this section by Alevor (indeed, the entire book) is a splendid source for those working to restore the heritage of the Ottoman-Armenian—in this case, the villager and his crat of making cloth from cotton or wool.

Even richer in scope is the 33-page chapter in Alevor’s book dealing with wheat cultivation. Detailed scenes on wheat sowing, reaping, and preparing the threshing,

16 Ibid., pp. 43-67.

216

follow in consecutive order. he sheaves were harrowed, followed by the winnowing and traying of the grain. Once the grains were separated from the bran and bits of straw and pebbles, they were boiled in water and let in the sun to dry (meynvil), then beaten with a flail, sieved, and milled. Ater all of this, the main food staple of Palu and Harput—bulgur—was ready for the table.17

Alevor continues to record his knowledge on traditional farming methods. He talks about mulberry (tut) cultivation, the making of syrup (rup), paste (pastegh), and vodka (oghi).18 He devotes many pages to grape cultivation, gardening, the grape harvest (egekit), and turning grapes into raisins, syrup, and wine.19

Of special significance is Alevor’s section on fishing,20 which deals with the varieties of fish that were to be found in the Eastern Euphrates (Aratzani/Murad Nehri), and how local Armenians fished for them. Most of the names of the fish were those used by Armenians of the time. In this way, Alevor has restored the local vocabulary of a group of people that had disappeared. He also di erentiates between the fishing nets used by urban and rural fishers and the methods they used in general. his section is one of the rare places in the book where Alevor puts aside his customary modesty and, speaking in the first person, relates that he is from Trkhe and once lived on the shores of the Aratzani. “I know well how and in what manner they fished there,” he writes, “especially since I had the opportunity to join the fishermen and participate in their work.”21 Alevor and Manoog Dzeron did more than merely restore scenes of a lost and forgotten rural way of life, however. While it is true that their works aren’t literary in nature, they conveyed an enthusiasm (particularly in the case of Manoog Dzeron) to recreate the village milieu, to relive certain moments in time.

Both writers wrote passionately about Armenian celebrations in the villages, and the customs and traditions associated with them. hey also wrote in detail about religious rituals, of baptisms, weddings, and burials. And they added dialogue, reproducing conversations that were likely to have occurred among villagers on these occasions. Manoog Dzeron employed this method the most. In one section, he describes the first stage in the preparation of a marriage, the khoskkap (binding word). he two mothers have already given their approval and the matter has now passed into the hands of the menfolk. he godfathers of the boy and girl, accompanied by a friend, pay a visit to the girl’s home. Here, Manoog Dzeron revives a conversation that would have taken place in the home, and ends the colorful dialogue when the specific amount to be paid by the boy’s family to the girl’s parents is agreed upon. he khoskkap—the

17Ibid., pp. 86-119.

18Ibid. pp. 120-134.

19Ibid. pp. 139-178.

20Ibid. pp. 218-228.

21Ibid., p. 219.

217

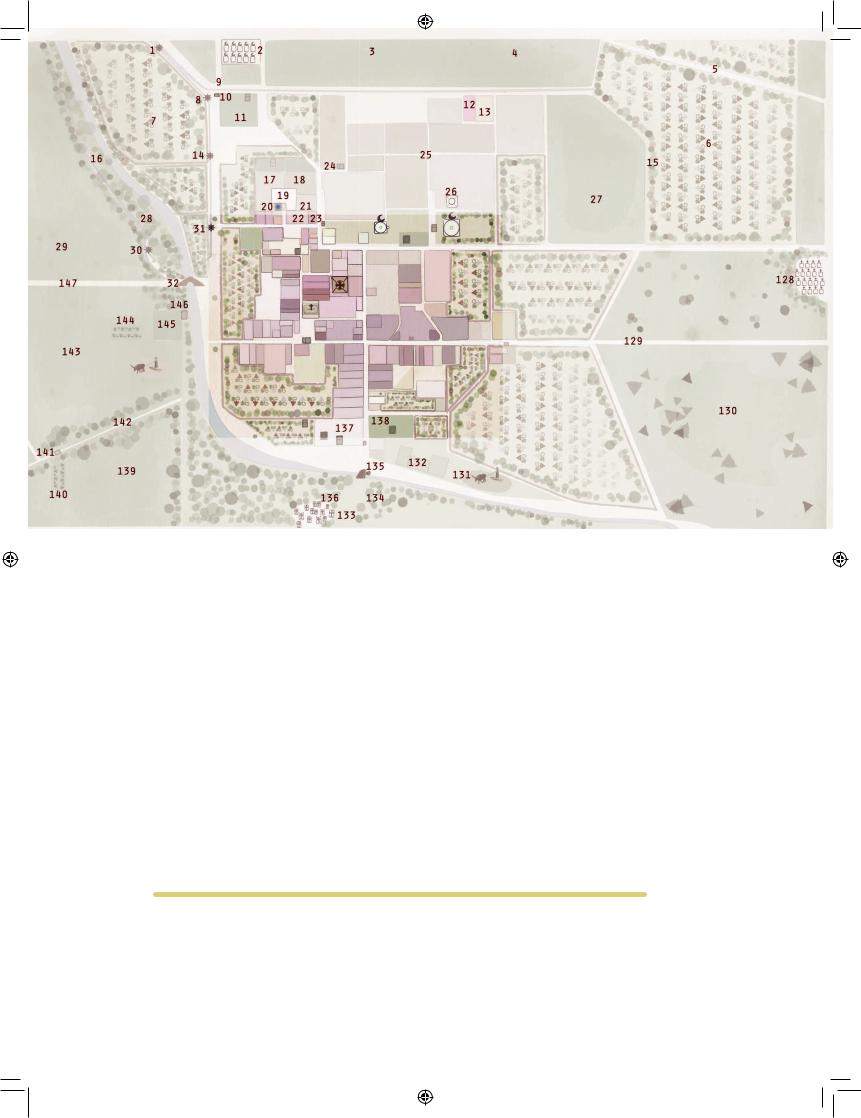

This central section of the map, enlarged for detail, shows the residential core of Parchanj.

1| Main mill 2| Turkish Cemetery 3| Arid land 4| Arid, sandy fields

5| Military Highway to Diyarbakir 6| Arid, sandy vineyards

7| Fenced vineyards 8| Kozkents mill 9| Town road

10| Khripka fountain 11| Hamit Agha’s garden 12| Elo (Usta Ovanes) 13| Prso 14| Tchektcheku mill

15| Oleaster16|-treeBalıkfenceGölü 17| Haji Mustafa Efendi 18| Haji Hamit Agha 19| Haji Osman Efendi 20| Well 21| Nijib Agha

22| Ter Manvel 23| Jani Güzel fountain 24| Tchukhus fountain 25| Turkish neighborhood 26| Public bath 27| Fields and gardens

28| Riverside woods 29| Fields on the Erdmnka River Road 30| Cotton mill 31| Krik’s mill

32| Stone bridge 33| Tzeron’s old house 34| Upper Torkank 35| Ter Manvel 36| Mghtesi Sahak 37| Adam 38| Depirmenk* 39| Kilirtzonk

40| Kuchik Ovan 41| Usta Khatchatur* 42| Boyaji* 43| Ter Khukas 44| Teotirmi

45| Koshkar Misak 46| Tefo’s factory 47| Yegho 48| Poyatz 48| Karo Gevo

49| Berber Ayon 50| Tefo Karo 51| Yetmish iki 52| Metz Torkank

53| Teotirmi’s fountain 54| Khoja Pushar 55| Protestant church 56| School 57| Koshkar Mkrtich 58| Kelen 59| Khmlenk

60| Mghtesi Gago 61| Hoto

first fundamental stage preceding a marriage—is thus formalized.22

In these conversations, Manoog Dzeron uses both the real names of Parchanj villagers— Tepo Karo, Kilarji Karamuyi kin Yeghso, Kelen Aruti kin Vardo, Jaghepan Hobbala Tono—and names similar to other, actual village residents, who recite their lines like stage actors in his book. And they all speak in the local dialect. By this time, readers of the book already have a cursory familiarity with these names and families, since the author has devoted the first 67 pages of his book23 to the Armenian villagers of Parchanj, their family lineages, and short biographical notes.

To remember and write, to write and draw: When restoring the past becomes the meaning of life

Manoog Dzeron’s book opens with a topographic map of Parchanj and area villages. Here, he depends on his memory and experience as the architect who once constructed the thoroughfares in those same villages. he map shows the area’s lakes, rivers, mountains, and roads. Two pages on, we find one of the most important elements that

22Dzeron, pp. 112-113.

23Ibid. pp. 31-98.

218

make this book unique: the street map of Parchanj village, which he has also drawn. He presents the houses of Armenian and Turkish families (each one bearing the owner’s name), the gardens, fields, churches, schools, mosques, and cemeteries.

he map and street plan are not the only sketches in Dzeron’s book. he work stands out with its numerous drawings, and it is evident that he has understood the importance of visual representations as a method of memory restoration. In this, Dzeron was assisted by his daughter Nvard Goshgarian (Koshkarian) and son Levon Dzeron, who reworked some of their father’s sketches. Alevor also used sketches, mostly to depict domestic, engineering, and crats tools, plants, and household items. We believe that his son, Paruyr Sargisian, helped with the sketches;24 Yet, they lack the precision and clarity of Manoog Dzeron’s images (for, the author of the Parchanj book was an architect by profession, and his daughter, a painter).

In any case, both authors, with their use of sketches as an art form to restore the routine of bygone days, hold a unique place among the hundreds of other authors of houshamadyans who, both prior and ater our two authors, either didn’t appreciate the importance of the “sketch/remember” concept, or did not have the means to put it into practice.

24 Interview with Haig Sarkisian (Alevor’s grandson), February 9, 2013.

The plan of Parchanj village was drawn by Manoog Dzeron and reworked by Houshamadyan.

62| Mghtesi Unan

63| Khrkhji Isayil*

64| Hoto Khatcho 65| Jemjem houses 66| School

67| Usta Minas 68| Yapan

69| Armenian church 70| Manasel

71| Tzeron Mkrtich 72| Ter Dages

73| Dages

74| Rabutali 75| Karo Karo

76| Madentsi Martiros 77| Pennan Peyros 78| Perishan

79| Torik Arut 80| Kamo Adam 81| Arbat*

83| Torik Khatcho 84| Torik Meko 85| Apuna

86| Rev. Petros

(continued on next page)

219

(continued from previous page)

87| Kuku 88| Balvtsonk 89| Arevik 90| Toro Karo

91| Tzeron Poghos Efendi 92| Koshkar Karo 93| Demirji

94| Mghtesi Asaturenk* 95| Gözlükji 96| Berber Avak 97| Hoppala

98| Mghtesi Asatur’s yard 99| Tato 100| Berber Yan’s Vineyard

101| Tzarko Karapet 102| Manan Baji Marmot 103| Vardatil Road 104| Lefent Fountain 105| Lower Khochkank 106| Odabash 107| Haltzonk 108| Podzachi Tato

109| Semurch’s store 110| Pennan Minas 111| Niko 112| Mghtesi Niko

113| Haji Osman 114| Taltapan 115| Khochik Marsup

116| Khochik Pagh. 117| Metz Khochkank 118| Tchatal Aghlu 119| Lower Mosque 120| Tchatal Fountain 121| Haji Hafez Agha 122| Upper Mosque 123| Galust Efendi 124| Ter Toros 125| Turkish School 126| Kelkel 127| Tat Hasan

128| Protestant cemetery 129| Road to Diyarbakir-Palu 130| Fields, pines 131| Wheat-thrashing field 132| Haji Küçük Agha 133| Shentil Road 134| Mulberry trees

135| Stone bridge (destroyed) 136| Armenian cemetery 137| Haji Tahir Bey 138| Tzeron Petros’ new house 139| Fields of trees 140| Vez’s vineyard 141| Yegho’s fountain 142| Khuylu Road 143| Fields 144| Kuskus’ vineyard

145| Hoto’s garden 146| Hoto’s fountain 147| Erdmnka River Road to

*Denotes entries Adanawhose spelling is uncertain, as not all names and terms were recorded clearly on the original map.

Instead, there are photographs. In almost all such memoir journals, photographs were used to varying degrees to show panoramas of towns and villages, the local church, school, a family or an individual. However, an author tasked with writing the history of his town does not always enjoy the luxury of having a rich photo collection at his/her fingertips. In this respect, the books written about Parchanj and Palu are expressive. Manoog Dzeron was able to collect family and individual photos from compatriots. Parchanj, in fact, was one of the villages where the migration of menfolk to the United States had already reached its peak by the end of the 19th century. he migrants were mostly newly married men who had let their wives and newborn behind to work in the factories of America, and send their wages back to their families. he men constantly dreamt of returning to their native village in a few years. Letters and photos maintained a connection between families, and the art of photography in the Harput valley underwent a period of development in subsequent years. Families would go to the large towns of their area, like Harput or Mezire, to have their photos taken, and would then send the prints to their relatives in America. Otentimes, photographers would make their rounds of the villages to ply their trade. Many Parchanj residents let, never to return, thus escaping the massacres of 1915. heir family photos oten served as their only remaining relic of their native village. In his mission to collect such photos, Manoog Dzeron was assisted by the Parchanj Compatriotic Union, which played a coordinating role between the author and former Parchanj residents scattered across the United States. In contrast, Alevor’s journal lacks a rich photographic archive, likely because he did not enjoy the assistance of a compatriotic society or an organization that could at least gather photos from former Palu residents living in various immigrant communities, especially in the United States, or cover the costs of publishing a work rich with photos.

Lacking in both books, however, are photographs of village life itself. Many of the other Armenian communities in the Ottoman Empire didn’t have panoramic village photos. A large number of villages have not only been forever emptied of their Armenian inhabitants, but of their Armenian community structures as well, which disappeared over the years to come. he Armenian past there is faceless and non-photographed; there are no visual means to connect local Armenian life to any representative structures or community landmarks. he photo is absent and, as Hirsch writes, it cannot serve as a bridge to the past, nor facilitate identification and a liation.25

But running counter to this tendency to wipe out all Armenian traces was a memory, held by the residents of those very same Ottoman places, by Armenians, Turks, Kurds, and others. he Turks and Kurds maintained a prolonged, forced silence regarding their past coexistence with Armenians, a theme which is not generally publicly alluded to by those of that generation. If the subject is publicly broached at all, Armenians are

25 Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory, p. 38.

220

portrayed in a negative light. hus, those Armenians who let their native home, never to return, are both the bearers of that memory and the ones who desired to publicize and pass on that memory. he exiles of this first generation began to produce a multitude of books in the memoir genre, striving to serve as witnesses to their native Armenian heritage, and working to prevent further destruction of a memory.

To write, to confirm, was their classic form of expression. But they were the native o spring of the village or town, and the memory linking them to this native world also had a visual and auditory nature, at the same time. he question was how, and by what medium, to transfer such legacies, especially at a time when they had none of today’s technological, multi-media possibilities.

Here, are two rare authors who, in their books, elevated sketching to a method for remembering and giving witness. his was a necessity, for when there are no photographs one must recreate the village, its various structures and rural implements, through memory. Let us take the floor plan drawn by Manoog Dzeron of the family house bearing the name of Khochkants, as an example.26 his two-story structure is displayed with architectural skill. It shows the various units of the village house—the

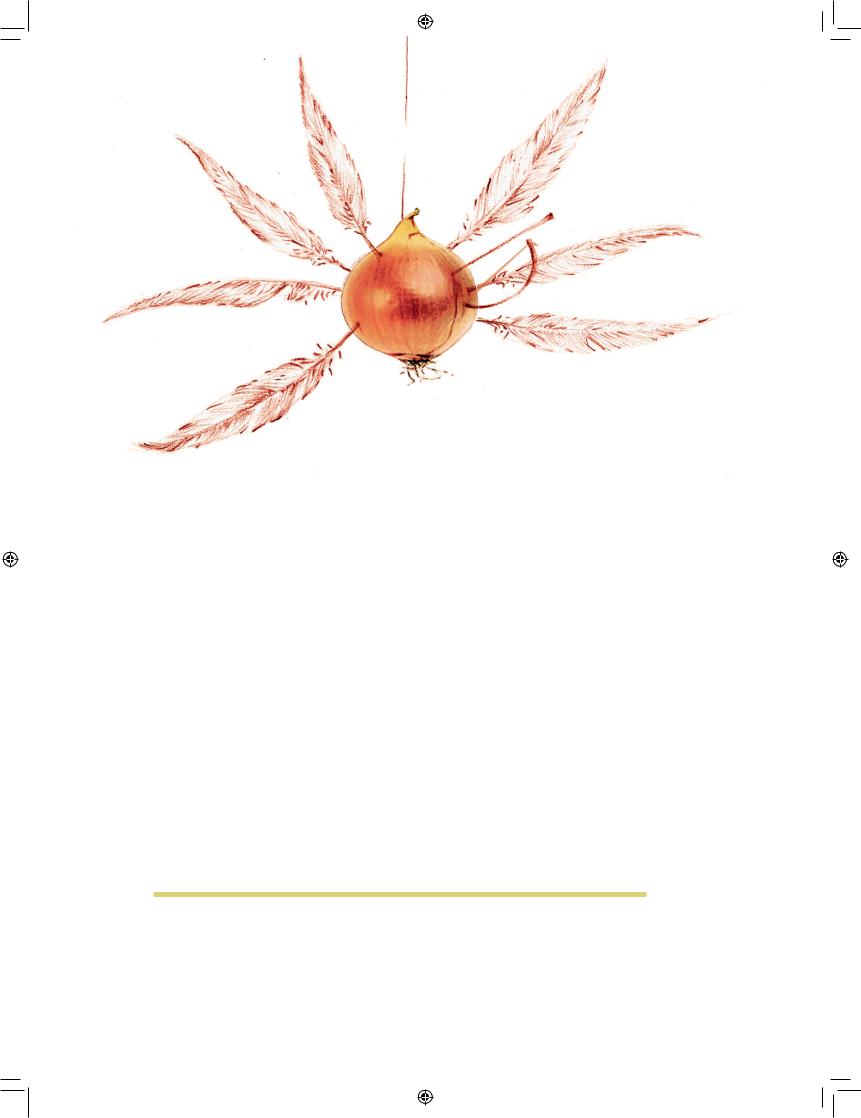

The khorbologh (or khulinchak) described by Alevor would hang from the ceilings of village homes throughout Metz Pahk (Great Lent).

Houshamadyan prepared the illustration based on Alevor’s sketches.

26 Dzeron, p. 44.

221

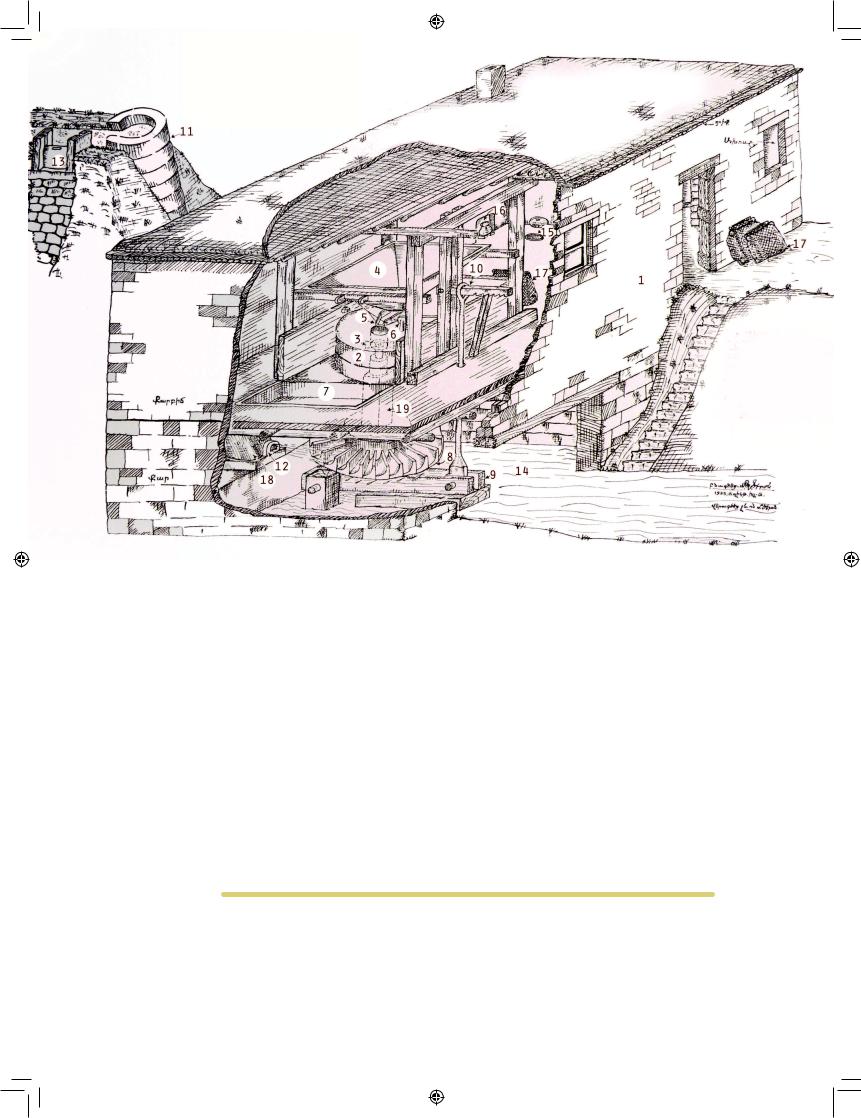

Drawing of the Parchanj village’s

tchaktchaku (tchagharj) mill:

1 | mill

2 | millstone

3 | driver (karmuchak)

4 | pail (takna)

5 | spout

6 | tchakhtchakh

7 | flour store (alertun)

8 | waterwheel

9 | support post

10 | lever

11 | water channel

12 | nozzle

13 | sluice gate

14 | millrace

15 | oven

16 | hearth

17 | aghvon

18 | beehive

19 | wooden post

Drawn by Manug Dzeron and redrawn by his son Levon M Dzeron in 1933, in Juliet, Illinois, USA

dordan (courtyard), kraktun (cooking room), tonir (circular oven), sagu (large, square, wooden gathering area built above the stables), akhor (barn), marag (haylot)—as well as the various household facilities—the ding (wheat crusher), dzitahank (oil press), triki pos (dung pit), and hor (well). he floor plan is quite tiny; it takes a magnifying glass to examine it. But, at its core, it is a monumental document. Various authors, including Manoog Dzeron and Alevor, wrote about the construction and architectural design of Armenian village houses in this region. And with this floor plan, we have before us a fantastic drawing that is more expressive and can more e ectively convey the true picture of daily village life. With the same skill, Manoog Dzeron also drew the floor plans for the only bathhouse in Parchanj and the mill owned by Hobbala Tono.27 here are 104 drawings in Manoog Dzeron’s book, which taken together reproduce the agricultural life of Parchanj. his rural daily lifestyle, with many of its traditional aspects, surely continued even ater the disappearance of the Armenians. But this lifestyle, in its sweeping scope, has today likely become a legacy of the past. It may have been the consciousness of eternal exile and a desire to preserve the local Armenian

27 Ibid. pp. 218, 228.

222