Tachjian V., Reconstructing Armenian Village Life Manoog Dzeron and Alevor

.pdf

Reconstructing Armenian Village Life

Manoog Dzeron and Alevor

Unique Authors of the ‘Houshamadyan’ Genre

Vahé Tachjian | Chief Editor of the Houshamadyan Project

203

To remember a native village or town, to collect written accounts, and photos and maps, of Armenian life there, to raise funds among Armenians with ties to that village, to publish a book that displayed all of this material. his was the decades-long dream of many who made up the first generation of Armenian exiles.

It was in this general environment, starting in the 1920’s, that books began to appear in succession in various Armenian diasporan communities by authors attempting to revitalize the Armenian past of their native community. Here, the written word had become a medium towards reconstructing the past, of times irretrievably lost.

hese authors, it seems, were convinced that they were the last survivors of the Ar- menian-Ottoman period. And they were certain that coming generations would be unable to reconstruct that past in a genuinely comprehensive manner. hus, they felt the need to immortalize this legacy of the past, this town or village of another time, by putting pen to paper and writing eyewitness testimonies.

We oten encounter the terms “Houshamadyan” (Book of Memories), “Hushakotogh” or “Hushartzan” (Memorial, Monument) in the titles or prefaces of these books. his is where the general term “houshamadyan” describing them comes from. In this way, the publication of a book is transformed into a ceremony marking the installation of a stone memorial—in this case, in memory of a deceased town or of a time irretrievably lost. But this memory-book is also tasked with preserving the life of the past, the memory of a lost town, with its history and traditions, heroes and glory, architecture, cuisine, song, and dance. In other words, the publication of a houshamadyan inevitably becomes what Marianne Hirsch has termed a post-memory,1 a legacy granted to coming generations. hese books number in the hundreds, and are oten similar in their internal composition, style, and content. Naturally, some are professional in nature, authored by the Armenian intellectuals of the day; others were written by individuals with few literary skills, who merely desired to leave an account of their native community. It would not be fair to classify these books based on some sort of qualitative internal ranking system; for, each of them represents a micro-history of a region, town, or village in the Ottoman Empire and is a rich source of—generally complementary—information. he scattered information contained in these books is similar to the multi-colored pieces of a mosaic—only by placing the pieces next to each other can one hope to recreate even

The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust

1 Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012); Marianne Hirsch, (Harvard University Press, 1997).

205

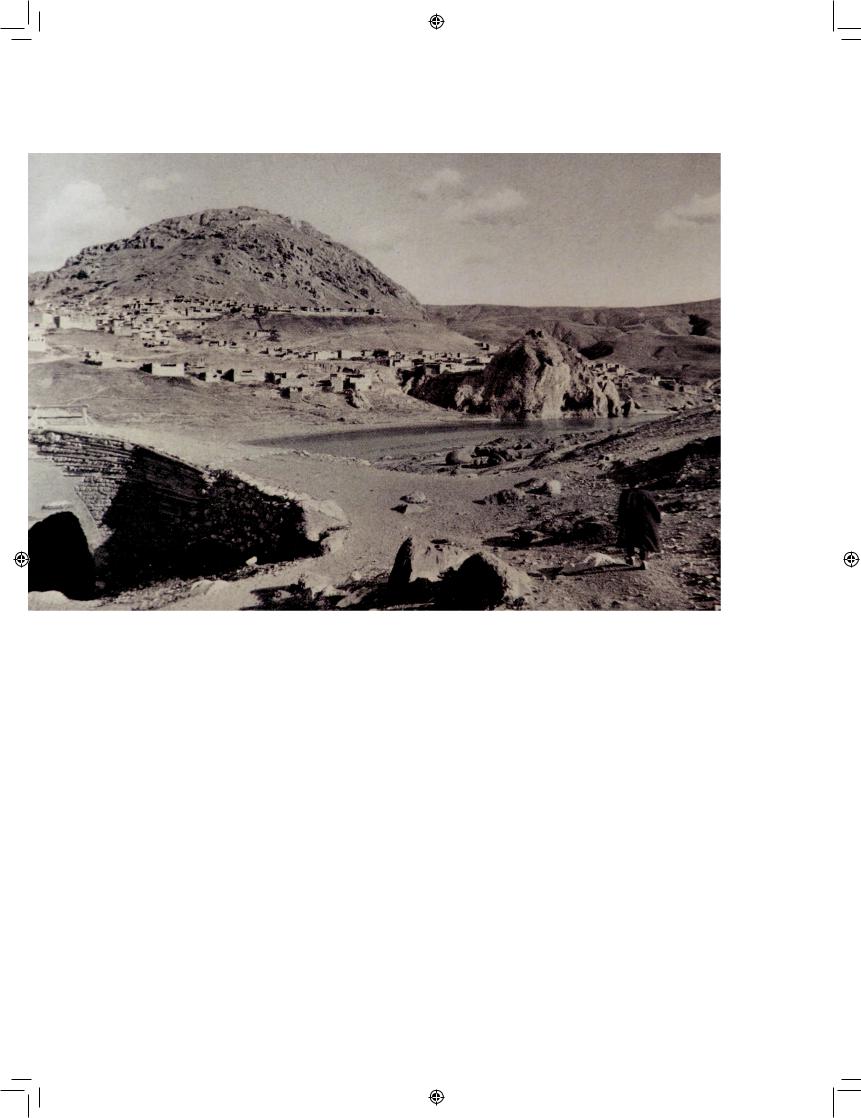

The town of Palu seen from the south.

Victor Pietschmann,

Durch kurdische Berge und armenische Städte, Adolf Luser Verlag, Wien, 1940, p. 160.

a rudimentary image of Ottoman-Armenians and their daily life, an image estranged from today’s world.

his article will focus on two books printed in the 1930’s that are widely regarded as the first publications of this genre:

Rev. Harutyun Sargisian (Alevor)’s . ,[Palu. Ir sovoruytnere, krtakan ou imatsakan

vichake yev barbare] [Palu: Its customs, educational and intellectual state, and dialect] (Cairo, 1932).

Manoog B. Dzeron’s . (1600-1937) Parchanj gyughe. Hamaynapatum (1600-1937)] [Parchanj villa-ge. Encyclopedia (16001937)] (Boston, 1938).

206

he two authors were largely successful in re-creating the Armenian village with its various facets of daily life.

When these two books were published, the rural and urban life of Ottoman-Armenian communities were still familiar to an entire émigré generation born and raised in the empire. he traditions, customs, cuisine, and songs described in these books lived on, to varying degrees, in the Armenian emigrant communities of the diaspora. he works of Manoog Dzeron (Manuk Tzeron) and Alevor can thus be regarded as genuine portrayals of a village lifestyle that was already familiar to many, and that for some continued to be a part of their daily lives. Alevor expressed this goal— the “obligation to collect, assemble, and immortalize the relics of a dying people”2—in the preface of his book.

he ones “dying,” in this case, were members of his own generation, and the obligation to inscribe a collective memory, a type of dedication to “the memory of my homeland,” was his. Manoog Dzeron said the same, albeit in a more emotive style, when he likened his book to a faraghat, “the property deed of our noble village which I have written with the ink of my tears for our future generations.”3 Yes, what they did was in the true nature of a mission: to transfer their personal (Palu or Parchanj) identity and memory, which also belonged to an entire generation, to their children, their grandchildren, and those yet to come.

In the minds of these authors, however, it was not only their generation, but their village, that was dying. Ater the annual floods, Dzeron writes, it was the Armenians who cleaned and repaired the springs and water pipes. But he’s learned from travelers there that the fountains and holding reservoirs (kehriz) of Parchanj have since already “dried up, the wells have crumbled and clogged, and only two flowing springs and one water well remain in the village.”4 While we don’t know how valid such information was, we are certain that the two authors were aware that in Turkey, starting in the 1920’s, a general policy was enacted that aimed at wiping out any physical traces of an Armenian presence. Armenian churches, cemeteries, and schools were to be destroyed in the years to come, and place names were to be Turkified: Parchanj/Perçenç village was to become Akçakiraz, and Palu, the town so memorialized by Alevor, was to be completely razed to the ground; a town bearing the same name was to be built some 2.5 kilometers to the west. he Armenian district of the city of Harput/Kharberd, so familiar to both authors, as it was where they lived and worked, was also completely destroyed. And the various Armenian-populated villages in the area were to be submerged underwater when a dam was built on the Euphrates.

2 Rev. Harutyun Sargisian (Alevor), . , [Palu. Ir sovoruytnere, krtakan ou imatsakan vichake yev barbare] [Palu. Its customs, educational and intellectual state, and dialect] (Cairo:

Sahag-Mesrob, 1932) p. 18.

3 Manoog B. Dzeron, . (1600-1937) [Parchanj gyughe. Hamaynapatum (1600-1937)] [Parchanj village. Encyclopedia (1600-1937)] (Boston, 1938) p. 251.

4 Ibid., p. 21.

207

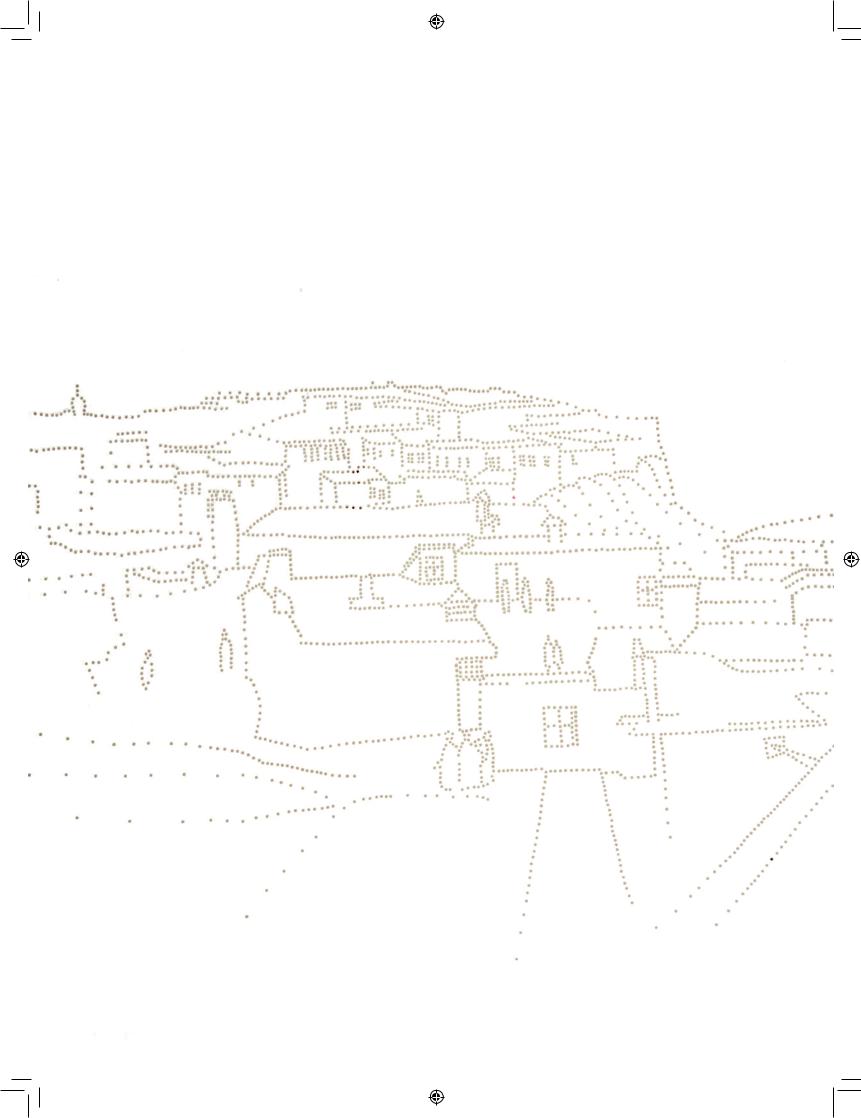

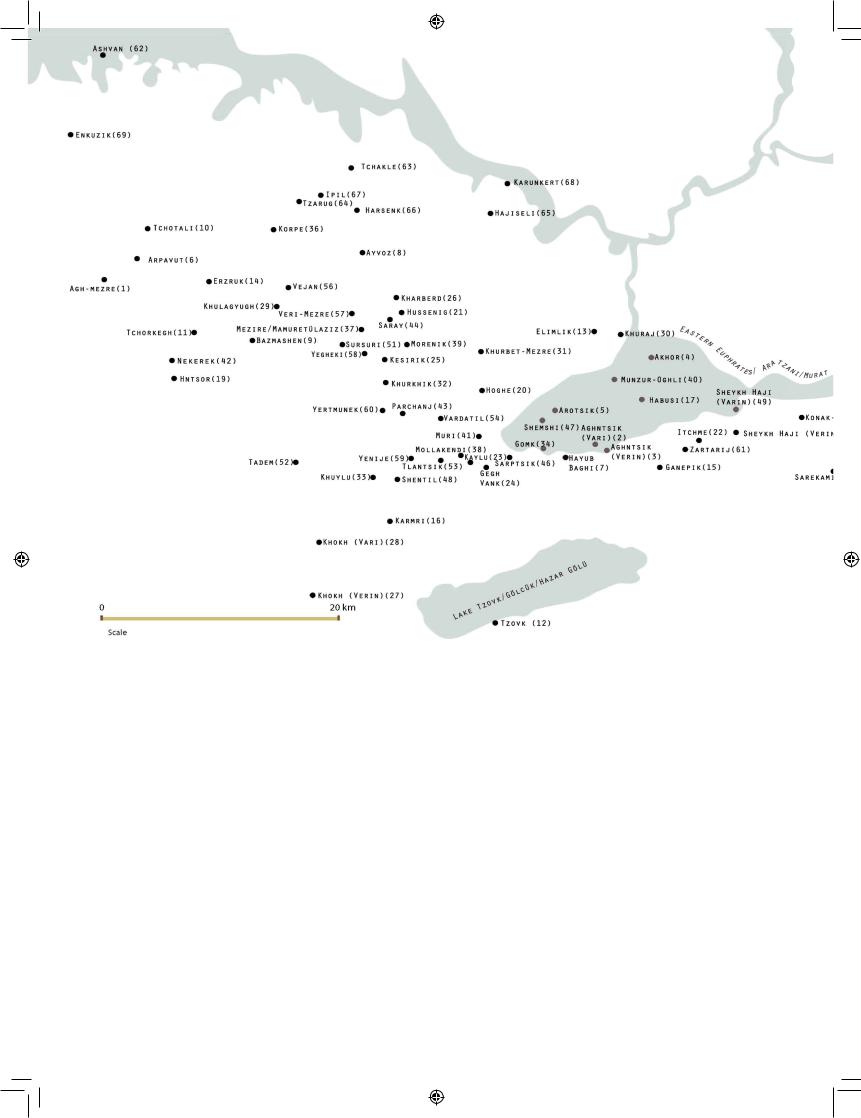

Plain of Harput/Kharberd with its Armenian towns and villages. The Aratzani River (Eastern Euphrates, Murat River) appears as it flows today, after a number of dams altered its original course. Map prepared by George

Aghjayan and reworked by Houshamadyan.

Present-day names:

1|Kavakpınar

2|Kavakaltı

3|Elmapınarı

4|Saraybaşı

5|Kuşluyazı

6|Alpağut 7|Ayıbağ Koy 8|Obuz 9|Sarıçubuk 10|Çöteli

hus, the authors’ goal was to preserve the legacy of a dying generation. hey knew that as the years rolled on, traditions would vanish, social perceptions would change, the Armenian language would, in many cases, become estranged, and interest in these things would wane. From this perspective, it’s no mere accident that many of the authors of such memoirs, especially in the United States, set out to have their works translated into English during their lifetime. hey knew well that a linguistic barrier would distance coming generations from their words. Of the two books presented here, only that of Manoog Dzeron has been translated into English. It took 47 years for Suren M. Seron, his son, to carry out that promise to his father.

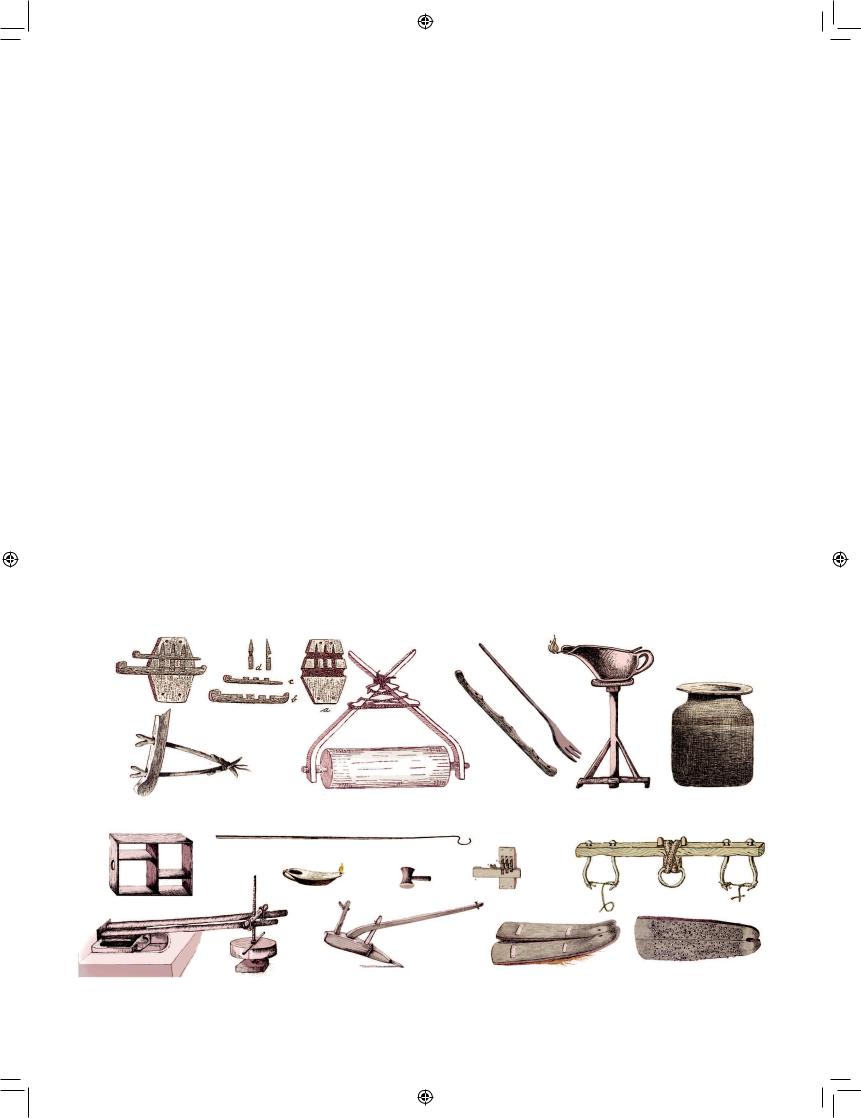

Today, when we attempt to resurrect the social landscape and daily life of OttomanArmenians through primary sources, the works of Manoog Dzeron and Alevor stand before us as shining beacons, fully illuminating our way forward. In fact, not only does a lost Armenian past spring anew from the pages of their books, but an entire rural heritage is reborn and appreciated: he construction of the village house, the

208

cultivation of the fields, the tools of the peasant toilers, the growing of grapes, wheat, and mulberries, and the food and drink prepared from them, the taxes, schools, the agha and bey, the housework, village games and holidays… hrough the richly colored pages of their books, these two authors open up the world of village life, and present the rural social milieu with deeply penetrating details. his prompts us to state that we are dealing with two distinct short tracts that brilliantly shed light on the Armenian village of the Ottoman Empire, on the life and prevalent social conditions that existed there. hrough these books, it is possible to closely learn about, study, and understand the villager of Harput or Palu—a figure that has since vanished without a trace.

Manoog Dzeron: The talented architect, or How a state banishes talent from its borders

Manoog Dzeron’s grandfather, Dzeron Varpet (master, in Armenian), was a famous carpenter in the village of Parchanj. He was so skilled in his crat that he began to engage in architecture, and was the mastermind behind the construction of the village bathhouse, the Surb Prkitch Church, and various mansions (konak). his Protestant resident of Parchanj had also traveled to Istanbul to help design some major structures.5 Master Dzeron’s son, Petros Dzeron (the father of Manoog Dzeron), would later perfect this crat and become a prominent cratsman in his own right, mastering carpentry, furniture-making, mechanics, architecture, and geometry.

Many of the churches that dotted the fields of Harput were his creations. He also served as the architect for the construction and reconstruction of the mosques located in the lower and upper neighborhoods of Parchanj. He and his brother Poghos collaborated on many of the government and religious structures in Mezire/Mamuretülaziz, including the Izzet Pasha Mosque, the government state house, the military barracks, the mekteb-i rüşdiye (government community school), the jail, and the military school, as well as the military workshop in Diyarbakir/Tigranakert, and the government building in Adana.6 It was in such a family of master cratsmen that Manoog Dzeron was born on December 15, 1862, in Parchanj. Ater graduating from the village school, he spent four years studying at the American Euphrates College in Harput, graduating in 1881. Later, he spent a short time teaching in Arapgir, Bitlis/Baghesh, and the Surb Hakob School in Harput. During his stay in Bitlis, he became acquainted with Mkrtitch Sarian,7 Markos Natanian,8 and Father Garegin Srvandztiants.9

5 Ibid., pp. 54-55.

6 Ibid., p. 55.

7 Born 1853 in Trabzon/Trebizond. School principal in Mush, community leader, and political activist. Died in Izmir in 1901.

8 Born 1862 in the Aygestan neighborhood of Van. School teacher, community leader, and political activist. Died in Paris in 1927.

9 Ibid., p. 58. Archbishop Garegin Srvadztiants. Born 1840 in Van (Aygestan). Author of the books Grots-brots (1874), Hnots-

11|Harmantepe

12|Hazar

13|Güzelyalı

14|Uzuntarla

15|Korucu

16|Yedigöze

17|Ikizdemir

18|Yolüstü

19|Örençay

20|Yurtbaşı

21|Ulukent

22|İçme

23|Karşıbağ

24|Güntaşı

25|Kızılay

26|Harput

27|Dedeyolu

28|Kavaktepe

29|Şahinkaya

30|Kıraç 31|Gurbet Mezre 32|Gümüşkavak 33|Kuyulu 34|Yenikapı 35|Konakalmaz 36|Körpe 37|Elazig 38|Mollakendi 39|Çatalçeşme 40|Munzuroğlu 41|Yünlüce 42|Bağlarca 43|Akçakiraz 44|Saray 45|Sarıkamış 46|Çağlar 47|Güngören 48|Bahçekapı 49|Aşağı Bağ 50|Yukarı Bağ 51|Olgunlar 52|Tadım 53|Doğankuş 54|Yazıkonak 55|Kuşhane 56|Sinan 57|Virane Mezre 58|Aksaray 59|Yeneci 60|Altınçevre 61|Değirmenönü 62|Muratcık 63|Çakıl 64|Kaplıkaya 65|Erbildi 66|Salkaya 67|Igopkoy 68|Çakmaközü 69|Dallıca

209

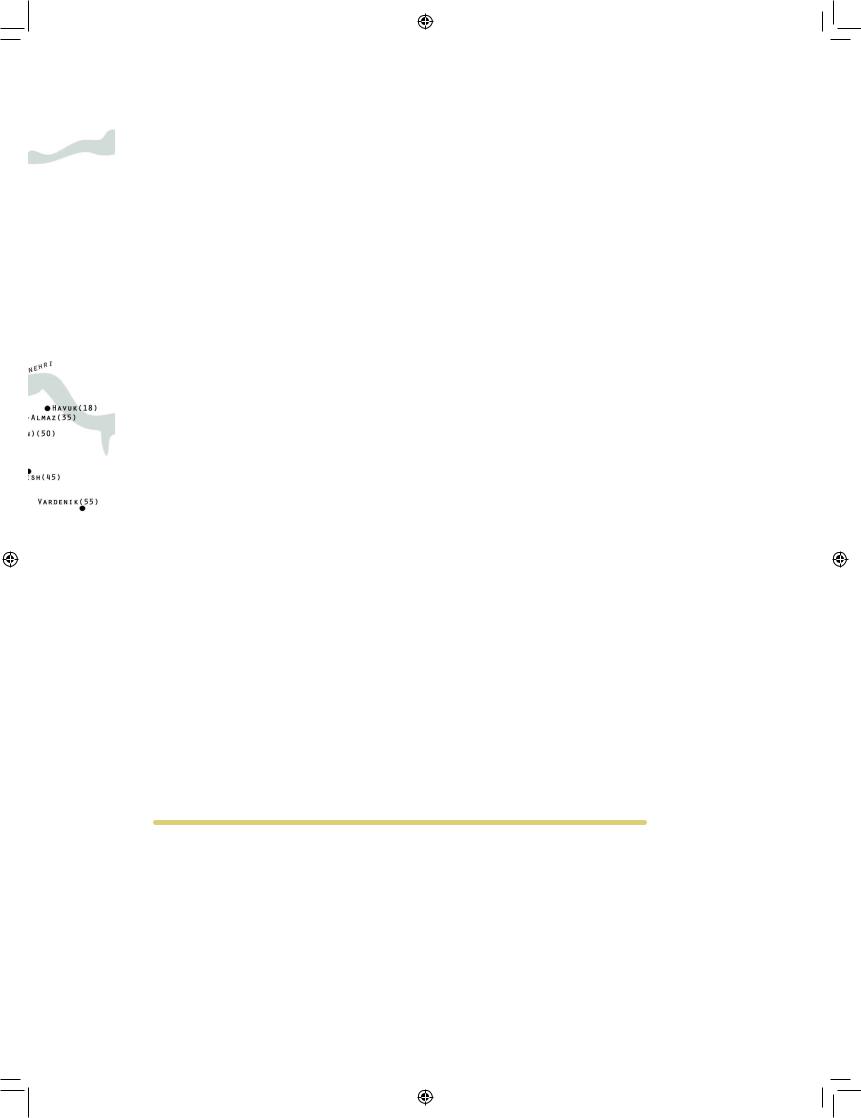

Manoog Dzeron

The bath of Parchanj— called the Efendvonts.

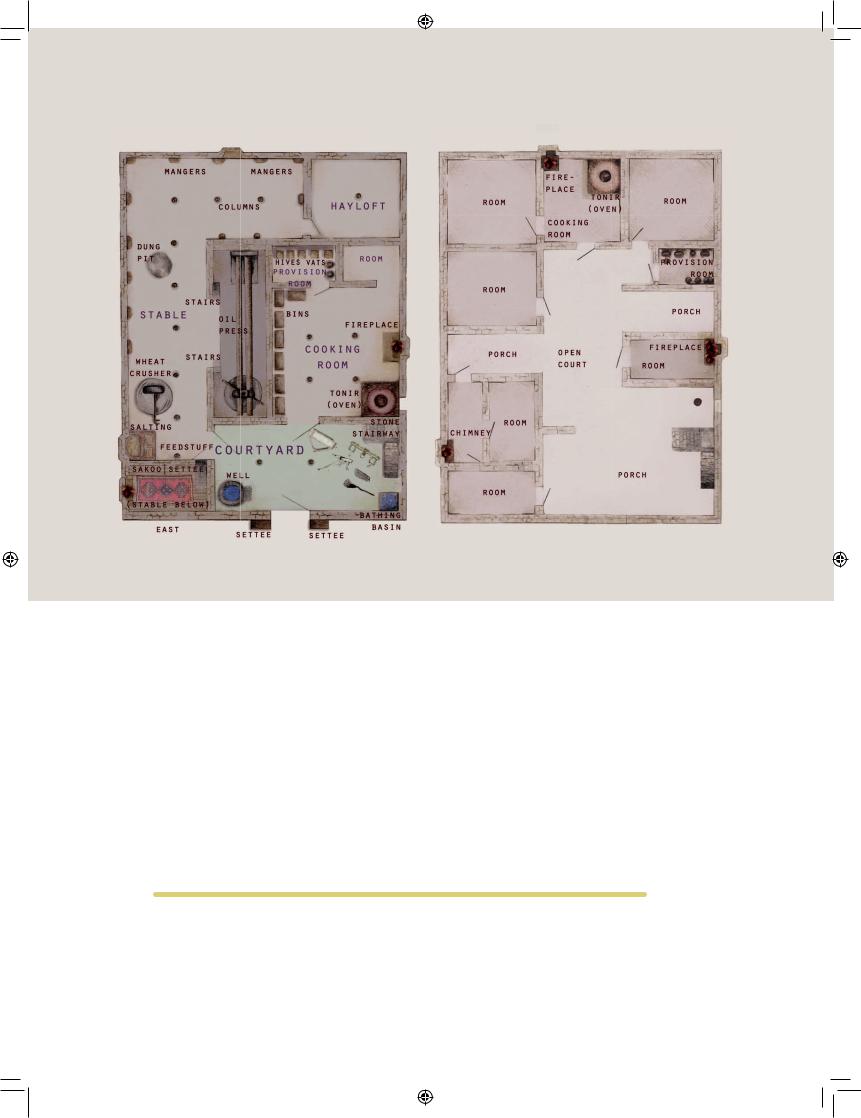

The plan was printed in Manoog Dzeron’s book. It was prepared by the author himself. The version presented on this page was reworked by Houshamadyan.

hose were the years of the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid II. Manoog Dzeron learned that a semi-military civil engineering boarding school (hendese-i mülkiye) had opened in Istanbul with a four-year curriculum, and that the tuition was “free to all Ottoman subjects without exception”. He let Harput and hurried to Istanbul to achieve his and his family’s dream, that is, to finally have a well-educated architect in the Dzeron family of talented architects. he school was under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of War, and the minister was personally known by Abik Efendi Unjian, one of the Armenian elites of Istanbul. Unjian interceded to facilitate Manoog Dzeron’s admittance. he young man from Parchanj passed the entrance exams, but was informed by Abik Efendi, who was told by the minister, that the sultan had issued a secret order that only Muslims could be accepted. he school’s principal suggested that if Dzeron converted to Islam,

norots (1874), Manana (1876), Toros Aghbar (1878-1879), Hamov-hotov (1884). Became Primate of the Trabzon Armenian Diocese in 1885. Died in Istanbul in 1892.

210

the doors of the school would open. Dzeron refused, and instead began to attend the tuition-based civil engineering school run by the Ministry of Construction. He took courses for two years there while teaching in the Feriköy neighborhood Armenian school. He also worked as a secretary for the neighborhood council to cover his living and educational expenses. Returning to Harput in 1896, he accepted the post of assistant provincial engineer and for the next four years constructed military highways. In 1897, he married Yeghsa, a woman from the village of Itchme, and their daughters Satenik and Nvard were born in Parchanj.10

In his book, Manoog Dzeron describes an interesting episode about the organized migration of Armenians, in which he participated. He writes that at the initiative of his brother Harutyun, and his father’s brother Poghos, 200 families of cratsmen organized a cooperative society with the aim of relocating en masse to the fertile plains of Pazarcık,

10 Dzeron, pp. 58-59.

The plan for a two-story building in Parchanj. The house belonged to an Armenian family bearing the surname Khojkants. The plan was printed in Manoog Dzeron’s book. It was prepared by the author himself, and then redrawn by his son, Levon Dzeron. The version presented on this page was reworked

by Houshamadyan. We have tried to maintain the authenticity of the original, while giving it a visually more appealing look to this amazing document.

211

Rev. Harutyun Sargisian (Alevor) – in the centre.

Cairo. Haig Sarkissian collection, Paris.

located south-east of the town of Marash. he society acquired a large plot of land ater paying a certain amount of cash to the local authorities, and the transaction was registered by the government of the vilayet of Aleppo, in which Marash was a subdistrict. Everything was done by the book, and permission for the move was obtained. he villagers of Parchanj were convinced that they could start a new life in Pazarcık, that is to say, that they could become owners of their land and property, pursue their crats, and work the land, far removed from the aghas and beys in Parchanj. But Kör Hamid, an influential Turkish bey in Parchanj, attempted to thwart the plan. Joining the conspiracy was Muroyents Ovanes, a close Armenian friend of the bey. Together they drated a fake letter alleging that the migrants were o to join forces with the Armenian rebels in Zeytun. he letter was handed to the vali (Provincial Governor) of Mezire, who didn’t give it much importance. he conspirators then handed the letter to the vicegerent of Aleppo, who immediately informed the central authorities in Istanbul. he relocation was halted and an investigation into the matter was launched, leading to the arrest of Poghos Dzeron, his brother Petros, and the latter’s two sons, Harutyun and Manoog. hey were jailed for two months, but the scandal came to light at the same time. Ater paying a large bribe to the Ottoman o cials in charge, the Dzerons were

212