О.Ф.Нестерова

ENGLISH STYLISTICS

СТИЛИСТИКА АНГЛИЙСКОГО ЯЗЫКА

Учебное пособие

В оронеж

2010

оронеж

2010

Федеральное агентство по образованию

Государственное образовательное учреждение

высшего профессионального образования

Воронежский государственный архитектурно-строительный университет

О.Ф.Нестерова

ENGLISH STYLISTICS

СТИЛИСТИКА АНГЛИЙСКОГО ЯЗЫКА

Учебное пособие

Под общей редакцией

профессора З.Е.Фоминой

Рекомендовано в качестве учебного пособия

редакционно-издательским советом Воронежского государственного

архитектурно-строительного университета для студентов,

обучающихся по специальности

«Переводчик в сфере профессиональной коммуникации»

В оронеж 2010

УДК 802.0(07)

ББК 81.2Англ я7

Н561

Рецензенты:

кафедра английского языка Воронежского государственного

педагогического университета;

С.В. Спиридонова, кандидат педагогических наук, доцент,

заведующая кафедрой современных языков и коммуникации

МОУ ВПО Воронежского института экономики и социального управления

Н561

|

Нестерова, О.Ф. English Stylistics. Стилистика английского языка: учеб. пособие для ПСПК / О.Ф.Нестерова; под ред. З.Е.Фоминой; Воронеж. гос. арх.-строит. ун-т. – Воронеж, 2010. – 79 с.

|

Учебное пособие предназначено для студентов специальности «Переводчик в сфере профессиональной коммуникации».

Основная цель пособия – ознакомить студентов, обучающихся по дополнительной образовательной программе «Переводчик в сфере профессиональной коммуникации», с наиболее важными понятиями стилистики и, в частности, стилистики английского языка, обучить стилистическим приемам и выразительным средствам английского языка. В пособии представлено описание различных функциональных языковых стилей, ориентированных на их практическое использование в профессиональной деятельности.

Материал пособия рассчитан для активного усвоения и самостоятельного изучения стилистики английского языка.

Ил. 1. Библиогр.: 32 назв.

ISBN 978-5-89040-265-3

© Нестерова О.Ф., 2010

© Воронежский государственный

архитектурно- строительный

университет, 2010

Введение

Учебное пособие «Стилистика английского языка» предназначено для студентов специальности «Переводчик в сфере профессиональной коммуникации». Практическое владение навыками профессионального перевода предполагает не только адекватное владение лексико-грамматической базой английского языка, но и знание различных языковых дисциплин. Стилистика занимает важную роль в курсе обучения профессионально ориентированному переводу.

В различных коммуникативных ситуациях люди используют разные способы выражения своих мыслей, т.е. разные стили общения. В отечественной лингвистике их принято называть функциональными стилями, в лингвистической зарубежной традиции – регистрами речи. Знание функциональных стилей и выразительных языковых средств, характерных для каждого стиля, весьма важно для специалиста, занимающегося переводом специальной литературы.

Данное учебное пособие состоит из 3-х разделов. В обзорном разделе представлены основные концепции и научные изыскания в области стилистики в изложении современных лингвистов и отражают наблюдения и взгляды ведущих ученых Оксфордской школы. Цель данного раздела – познакомить студентов с отдельной терминологией, необходимой для восприятия текста с точки зрения стилистики языка. Данный раздел следует считать предварительным этапом к курсу прикладной стилистики.

Второй раздел учебного пособия «Стилистика английского языка» представляет собой курс, состоящий из 12 лекций, в ходе которого студенты ПСПК знакомятся с фигурами, тропами, стилистическими приемами, выразительными средствами и основами стилистического анализа. Приводятся примеры из художественных и публицистических произведений зарубежных авторов.

Специальная терминология представлена в научно-терминологическом справочнике и включена в третий раздел пособия.

Каждый раздел пособия включает в себя список рекомендуемой литературы, а в разделе «Лекции» предложены тематические вопросы для самоконтроля. В конце пособия указан общий библиографический список, включающий основную литературу, дополнительную и словари. Основой для составления данного пособия послужили учебники по стилистике английского языка ведущих отечественных и зарубежных авторов (Арнольда И.В., Гуревича В.В., Гальперина И.Р., Verdonk P.), а также новейшие лингвистические исследования в данной области и справочная литература.

Предлагаемое учебное пособие позволит обучаемым овладеть основами стилистики языка, что будет способствовать развитию навыков адекватного профессионально ориентированного перевода с учетом всех требований, предъявляемых к данному виду работы.

S E C T I O N I

Survey

1

The concept of style

The concept of style is an old one; it goes back to the very beginnings of literary thought in Europe. It appears in connection with rhetoric rather than poetic.

Stylistics is concerned with the study of style in language. But what is style in language? How is it produced? How can it be recognized and described?

The term ‘style’ (without specific reference to language) is one which we use so commonly in our everyday conversation and writing that it seems unproblematic: it occurs so naturally and frequently that we take it for granted without enquiring just what we might mean by it. Thus, we regularly use it with reference to the shape or design of something (“the elegant style of a house”), and when talking about the way in which something is done or presented (”I don’t like his style of management”). When describing someone’s manner of writing, speaking or performing we may say “She writes in a vigorous style”. We also talk about particular styles of architecture, painting, dress and furniture when describing the distinctive manner of an artist, a school or a period. And finally, when we say that people or places have “style”, we are expressing the opinion that they have fashionable elegance, smartness or a superior manner (“They live in grand style”).

Style in language can be defined as distinctive linguistic expression. So stylistics, the study of style, can be defined as the analysis of distinctive expression in language and the description of its purpose and effect.

Different genres, or types, of text containing specific features of style create particular effects.

Style as motivated choice

Style involves a choice of form without a change of message. Style is indeed a distinctive way of using language for some purpose and to some effect. In order to

achieve this purpose and effect all the devices are used, different forms and structures are chosen.

So in making a stylistic analysis we are not so much focused on every form and structure in a text, as on those which stand out in it. Such conspicuous elements rouse the reader’s interest or emotions. In stylistics this psychological effect is called foregrounding, a term which has been borrowed from the visual arts. Such foregrounded elements often include a distinct patterning or parallelism in a text’s typography, sounds, word choices, grammar, or sentence structures. Other potential style markers are repetitions of some linguistic element, and deviations from the rules of language in general or from the style you expect in a particular text type or context.

Style in context

Style does not arise out of a vacuum but that its production, purpose and effect are deeply embedded in the particular context in which both the writer and the reader play their distinctive roles. We should distinguish between two types of context: linguistic and non-linguistic context. Linguistic context refers to the surrounding features of language inside a text, like the topography, sounds, words, phrases and sentences which are relevant to the interpretation of other such linguistic elements.

The non-linguistic context is a much more complex notion since it may include any number of text-external features influencing the language and style of a text. Conscious or unconscious choices of expression which create a particular style are always motivated and inspired by contextual circumstances in which both writers and readers are in various ways involved.

2

Style in literature

When we encounter a text, we recognize it as of a particular and familiar kind, as belonging to a particular genre, for example a newspaper article, a blurb, a menu, or an insurance policy. We have an idea of what to expect.

So if you have become familiar with the stylistic conventions of the genre of poetry, you will know that the language of poetry has the following characteristics: its meaning is often ambiguous and elusive; it may flout the conventional rules of grammar; it has a peculiar sound structure; it is spatially arranged in metrical lines and stanzas; it often reveals foregrounded patterns and its sounds, vocabulary, grammar, or syntax, and last but not least, it frequently contains indirect references to other texts.

Text type and function

The majority of the texts have some practical function in that they have intentions which can be related to the real world around us. For instance, a headline encourages us to read a news story, a publisher’s blurb encourages us to buy a book, and an advertisement is designed to promote a product.

This, of course, prompts the compelling question as to what the function might be of text types or genres like poetry, novels and plays, all of which are traditionally designated as literary texts. The first thing we might note is that whatever the function of poetry may be, it bears no relation to our socially established needs and conventions, because unlike non-literary texts, poetry is detached from the ordinary contexts of social life. To put it differently, poetry does not make direct reference to the world of phenomena but provides a representation of it through its peculiar and unconventional uses of language which invite and motivate, sometimes even provoke, readers to create an imaginary alternative world. Perhaps it is its essential function, namely it enables us to satisfy our needs as individuals, to escape from our socialized existence and to find a reflection of our conflicting emotions.

Certainly, our perceptions are different. We have different expectations and different emotions, out interpretation of the text may differ from others and may include total rejection.

3

Text and discourse

The nature of text

When we think of a text, we typically think of a stretch of language, either spoken or written, complete in itself and of some considerable extent: a business letter, a leaflet, a news report, a recipe, and so on. But there appears a problem when we have to define units of language which consist of a single sentence, or even a single word, which are experienced as texts because they fulfil the basic requirement of forming a meaningful whole. Typical examples of such small-scale texts are public notices like ‘K e e p o f f t h e g r a s s’, ‘K e e p l e f t’, ‘D a n g e r’, ‘R a m p a h e a d’, ‘E x i t’.

These minimal texts are meaningful in themselves, and therefore do not need a particular structural patterning with other language units. In other words, they are complete in terms of communicative meaning. It should be recognized that the term ‘text’ often refers to a definable communicative unit with a social or cultural function. Thus a casual conversation, a poster, a poem, or an advertisement would be referred to as texts. So, if the meaningfulness of texts does not depend on their linguistic size, what else does it depend on?

Consider the road sign ‘R a m p a h e a d’. When you are driving a car and see this sign, you interpret it as a warning and you know what to do. From this it follows that you recognize a piece of language as a text, not because of its length, but because of its location in a particular context. And if you are familiar with the text in that context, you know what the message is intended to be.

But now suppose you see the same road sign in the collection of a souvenir-hunter! Of course, you still know the original meaning of the sign, but because of its dissociation from its ordinary context of traffic control, you are no longer able to act on its original intention. We can conclude that, for the expression of its meaning, a text is dependent on its use in an appropriate context.

The nature of discourse

Discourse is one of the most widely used and overworked terms in many branches of linguistics, stylistics, cultural and critical theory.

It covers all those aspects of communication which involve not only a message or text but also the addresser and addressee, and their immediate context of situation. Discourse would therefore refer not only to ordinary conversation and its context, but also to written communication between writer and reader. In this broad sense, discourse ‘includes’ text, but the two terms are not always easily distinguished, and are often used synonymously.

The meaning of a text does not come into being until it is actively employed in a context of use. This process of activation of a text by relating it to a context of use is called discourse. To put it differently, this contextualization of a text is actually the reader’s (and in the case of spoken text, the hearer’s) reconstruction of the writer’s (or speaker’s) intended message. A text may be in some written form, or in the form of a sound recording, or it may be unrecorded speech. But in whatever form it comes, a reader (or hearer) will search the text for cues or signals that may help to reconstruct the writer’s (or speaker’s) discourse. However, just because he or she engaged in a process of reconstruction, it is always possible that the reader (or hearer) infers a different discourse from the text than the one the writer (or speaker) had intended.

Textual and contextual meaning

In order to derive a discourse from a text we have to explore two different sites of meaning: on the one hand, the text’s intrinsic linguistic or formal properties (its sounds, typography, vocabulary, grammar and so on) and on the other hand, the extrinsic contextual factors which are taken to affect its linguistic meaning. These two interacting sites of meaning are the concern of two fields of study: semantics is the study of formal meanings as they are encoded in the language of texts, that is, independent of writers and readers set in a particular context, while pragmatics is concerned with the meaning of language in discourse, that is, when it is used in an appropriate context to achieve particular aims. Pragmatic meaning is not an alternative to semantic meaning, but complementary to it.

We distinguished two kinds of context: an internal linguistic context built up by the language patterns inside the text, and an external non-linguistic context drawing us to ideas and experiences in the world outside the text. The latter is a very complex notion because it may include any number of text-external features influencing the interpretation of a discourse. We can specify the following components:

1. the text type, or genre;

2. its topic, purpose, and function;

3. the immediate temporary and physical setting of the text;

4. the text’s wider social, cultural and historical setting;

5. the identities, knowledge, emotions, abilities, beliefs, and assumptions of the writer and reader;

6. the relationships holding between the writer and reader;

7. the association with other similar or related text types.

4

Perspectives on meaning

Linguistic features in texts can be interpreted differently as representing an event or situation from a particular perspective or point of view. The notion of perspective is itself problematic.

Perspective in narrative fiction

If the author changes the perspective or point of view from which a fictional world is presented it will result in a different story and give rise to a different interpretation.

We make sense of a text by relating it to the context of our knowledge, emotions, and experience. Bur since such contexts will be different for particular readers, so interpretations will vary also.

At one level of perception, we might all agree on what a text is about, but diverge greatly in our interpretation of it.

The first question that inevitably arises as soon as we start reading a novel or short story is who the narrator is, whose voice we are supposed to be hearing, and therefore whose version of events. We know who the author is, the person who actually produced the text, but that is, of course, not the same thing at all.

Stylistic markers of perspective and positioning

To begin with, at various points in the text the narrator refers to persons, places, and times by means of words and phrases like ‘I’, ‘my’, ‘you’, ‘here’, ‘nearby’, and the present and past tenses of verbs, for example ‘owns’, ‘was’, ‘lived’, and ‘tell’. In a face-to-face conversation these terms would be easily understood because speaker and listener would share the same physical context of time and place. But in writing things are different. Of course, readers know the textual or semantic meaning of these words, but they do not know their situational or pragmatic meaning. This is because they cannot see the people referred to by ‘I’, ‘my’, and ‘you’ in the flesh, nor can they actually observe the places indicated by ‘here’, ‘nearby’, or check the times in relation to the verb tenses. However, prompted by their experience of the real world and their knowledge of the stylistic conventions of fiction, readers will understand these linguistic expressions as representations of the people, places, and times in the story, and will act on them as cues to imagine themselves as participating in the situation of the fictional world of the discourse.

Deixis

The technical term for these textual cues is deictics, while the psycholinguistic phenomenon as a whole, which is fundamental to all spoken and written discourse, is usually called deixis (from a Greek word which means ‘pointing’ or ‘showing’). Deictics may serve to ‘point to’ the listener’s or reader’s attention to the speaker’s or narrator’s spatial and temporal situation. Then there are also deictics which refer the listener or reader to the people taking part in the events of the discourse. Hence we may distinguish three types of the deictics: place deictics, which include adverbs such as ‘here’ (near the speaker), ‘there’ (away from the speaker); prepositional phrases like ‘in front of’, ‘behind’, ‘to the left’, ‘to the right’; the determiners or pronouns ‘this’ and ‘these’ (near the speaker) and ‘that’ and ‘those’ (away from the speaker), and the deictic verbs ‘come’ and ‘bring’ (in the direction of the speaker) and ‘go’ and ‘take’ (in a direction away from the speaker). Another category is time deictics, which include items such as ‘now’, ‘then’, ‘today’, ‘yesterday’, ‘tomorrow’, ‘next day’. Other important time deictics are the present and past tenses of full verbs (for example, ‘play/s’, ‘played’; ‘go/es’, ‘went’) and of auxiliaries (for example, ‘have’ and ‘had’). The third category is person deictics, which include the first person pronoun ‘I’ (and its related forms ‘me’, ‘my’, and ‘mine’) and the second person pronoun ‘you’ (and its related forms ‘your’ and ‘yours’). They are the terms people use to refer to themselves and to talk to each other.

The deictics in a narrative text prompt the following important questions: Who is telling the story? Who is the narrator talking to? Where and when do the events take place? And from whose perspective is the story told?

Reading a novel is not only a matter of finding out what is told, but also how it is told. In other words you cannot separate content (the ‘what’) from form (the ‘how’). Undoubtedly, the most important formal aspect is the author’s choice of perspective. It is the controlling consciousness through whose filter readers experience the events of the story. And a subjective first-person perspective can draw readers into the illusion of presence in the fictional world by inducing them to fill the vacant role of the second-person addressee.

5

The language of literary representation

Perspective in third-person narration

The first-person narrator necessarily assumes a participant role within the fictional context and so adopts a subjective perspective on events. We might propose that the third-person narrator, on the other hand, takes up the non-participant role of observer and so adopts an objective point of view. But things are not so simple. In the non-fictional world, it is true, it would be normal to use third-person terms of reference to talk about objective events that can be observed and reported on: ‘The woman was sitting at her table writing letters. She was wearing a red dress. The man entered the room. He picked up a book.’ And so on. This is straightforward enough. But in fiction we frequently find that the narrator uses third-person reference to describe things which is quite impossible to observe. Consider, for example, the following passage from Lawrence’s novel Women in Love:

(1)He went into her boudoir, a remote and very cushiony place. (2) She was sitting at her table writing letters. (3) She lifted her face abstractedly when he entered, watched him go to the sofa, and sit down. (4) Then she looked down at her paper again.

(5) He took up a large volume which he had been reading before, and became minutely attentive to his author. (6) His back was towards Hermione. (7) She could not go on with her writing. (8) Her whole mind was a chaos, darkness breaking in upon it, and herself struggling to gain control with her will, as a swimmer struggles with the swirling water. (9)But in spite of her efforts she was borne down, darkness seemed to break over her, she felt as if her heart was bursting. (10) The terrible tension grew stronger and stronger, it was most fearful agony, like being walled up.

The first six sentences here report observable events from a third person perspective in a conventional way: ‘He went … She was sitting …writing letters. She lifted her face … he entered, watched him … she looked down … He took up a large volume … His back was …’. But with (7) there is a transition to a different perspective. ‘She could not go on with her writing’ expresses a state of mind which is inaccessible to observation, and which only she herself can be aware of. Sentences (8) to (10) directly express the personal experience of the character. The narrator has moved inside the character’s mind. And so we have a third-person expression of first-person experience. And as the perspective changes, so does the use of language. The most obvious difference is in sentence length. The text on each side of the transitional sentence (7) consists of exactly the same number of

words (68) but they combine into six sentences in the first part and only three in the second. But the sentences do not only differ in length, but also in their syntax. Those of the first part of the text are structurally straightforward and describe a sequence of events in an orderly linear way: ‘He went … she was sitting … She lifted her face … he entered … [she] watched him …’ and so on. After the transition, however, the syntax becomes disordered, phrases do not fit together with neat linearity, but accumulate without clear structural connections. What is expressed is not a series of events but a sudden outbreak of sensations all happening at the same time. The chaos in Hermione’s mind, and her struggle for the control of her feelings, are not just described but directly represented by the syntax itself.

In this text we see a shift in narrative perspective from that of the third-person observer to that of first-person participant, and a corresponding change in the way language is structured to achieve an appropriate representation.

In this text, the narrator shifts perspective but remains within one fictional context of time and place. But narrators can also shift perspective by taking up different contextual positions.

Speech and thought representation

There are also times, however, when the narrator delegates perspective to the characters and leaves to speak for themselves. In this case we are presented with a record of direct speech (DS). Let us see the extract from the poem by John Betjeman.

She puts her fingers in his as, loving and silly,

At long-past Kensington dances she used to do

‘It’s cheaper to take the tube to Piccadilly

And then we can catch a nineteen or a twenty-two’.

In the first two lines the narrator first describes what happens in the observable present (‘She puts her fingers in his’) and then shifts to an omniscient perspective to express her feelings, and to recall her personal past. In the last two lines we are presented with the direct speech of her actual utterance.

In the preceding verse of the poem we also find lines within quotation marks, but here they do not express what the character actually says but what is going on in his mind.

No hope. And the iron nob of this palisade

So cold to the touch, is luckier now than he

‘Oh merciless, hurrying Londoners! Why was I made

For the long and the painful deathbed coming to me?’

Here is presented direct thought (DT).

But the use of direct speech is not the only kind of speech representation we find in fiction. Indirect speech (IS) is also common, as indeed it is in non-literary use. Here is an utterance from Hemingway’s short story ‘Hills Like White Elephants’:

‘The beer’s nice and cool’, the man said.

It could be rendered as follows:

The man said (that) the beer was nice and cool.

In the case of indirect speech, the narrator reports only the content of what the character has said, but not its exact wording (it is , in this sense, reported rather than recorded speech). This allows the narrator to intervene and to interpret the character’s original words, thereby, again, shifting perspective:

The man commented on how nice and cool the beer was.

The man said, appreciatively, that the beer was nice and cool.

The representation of indirect thought (IT), of course, presupposes an even greater degree of narrator initiative:

The man thought that the beer was nice and cool.

These ways of representing direct and indirect speech and thought conform to linguistic conventions which apply to written language in general. And now we see a kind of representation which is more specifically literary:

The man drank the beer. Goodness, how nice and cool it was!

The expression ‘Goodness’, suggests a direct record of what was said or thought but the past tense ‘was’ suggests that this is an indirect report. What we have here is a blend of both, a hybrid form. This has been referred to as free indirect speech (FIS) or free indirect thought (FIT). It should be noted that it has become customary to roll these forms into one and to use the umbrella term free indirect discourse (FID).

A further development of these modes of thought representation is to be found in the so-called stream of consciousness technique through which the narrator designs a style which creates the illusion that, without his or her interference, readers have direct access to the mental processes of the characters, i.e. to their inner points of view. As a result, the reader sees the fictional world through the ‘mental window’ of the observing consciousness of the characters.

Stream of consciousness is now widely used in modern fiction as a narrative method to reveal the character’s unspoken thoughts and feelings without having recourse to dialogue or description. Here is an example from James Joyce’s Ulysses:

Ba. What is that flying about? Swallow? Bat probably. Thinks I’m a tree, so blind. Have birds no smell? Metempsychosis. They believed you could be changed into a tree from grief. Weeping willow. Ba. There he goes. Funny little beggar. Wonder where he lives. Belfry up there. Very likely. Hanging by his heels in the odour of sanctity. Bell scared him out, I suppose. Mass seems to be over. Could hear them all at it. Pray for us. And pray for us. Good idea the repetition.

This piece of first-person discourse takes us right into the mind of the central figure in the novel. His thought processes are directly projected. The fragmented syntax, the staccato phrases, the use of the present tense, all create a style which dramatizes the unedited thoughts and impressions of the character as they occur. And all orientational expressions like ‘There he goes’ and ‘Belfry up there’ are related to the character’s point of view; he is the centre of every thing that is going on. And the extract is entirely free from reporting clauses and quotation marks.

This is the style of interior monologue, through which the reader is enabled to tune in to the character’s train of thought or stream of consciousness, seemingly without being hampered by the presence of the narrator.

Список рекомендуемой литературы

1. Birch, David. Language Discourse and Literature /D. Birch. - Unwin Hyman, 1989. – p. 310.

2.Brogan, T.V.F. The New Princeton Handbook of Poetic Terms /T.V.F. Brogan. - Princeton University Press, 1994. – p. 117.

3.Carter, Ronald & Nash, Walter. A Guide to Styles of English Writing /R. Carter, W. Nash. - Blackwell, 1990. – p. 158.

4.Cook, Guy. Discourse and Literature /G. Cook. - Oxford University Press,1994. – p. 190.

5.Leech, Geoffrey N. & Short Michael H. Style in Fiction /G.N. Leech, M.H. Short. - Longman, 1981. – p. 91.

6.Short, Mick. Exploring the Language of Poems, Plays & Prose /M.Short. - Addison Wesley Longman, 1996. – p. 119.

7.Toolan, Michael. Language in Literature. An Introduction to Stylistics /M. Toolan. - Arnold, 1998. – p. 84.

8.Verdonk, Peter. Stylistics /P. Verdonk. - Oxford University Press, 2005. – p. 124.

9.Verdonk, Peter. A Brief Survey from Classical Rhetoric to Cognitive Stylistics /P. Verdonk. – Oxford University Press, 1999. – p. 110.

10.Wales, Katie. A Dictionary of Stylistics. - 2-nd edn. - Pearson Education, 2001. – p. 458.

11.Widdowson, H.G. Practical Stylistics. An Approach to Poetry /H.G. Widdowson. - Oxford University Press, 1992. – p. 75.

S E C T I O N II

LECTURES

Lecture 1: GENERAL NOTES ON STYLE AND STYLISTICS. STYLISTICS AS A SUBJECT

People have been interested in the questions of style for a long time. We can say, rhetoric is the “mother” of modern stylistics, its objective was to teach the art of public speech (the ability to express thoughts with fine words), the well-organized speech, ways of speech decoration and concept of style. Aristotel was the first to start the theory of style, metaphor, to oppose poetry to prose.

The word “style” derived from the Latin word “stilus” which meant a short stick sharp at one end and flat at the other used by the Romans for writing on wax tablets. Now the word “style” is used in many senses. The first concept is so broad that it is hardly possible to regard it as a term. Even in linguistics the word “style” is used very widely. The majority of linguists agree that the term presupposes the following: 1) the aesthetic function of language; 2) expressive means in language; 3) synonymous ways of rendering one and the same idea; 4) emotional colouring in language; 5) a system of special devices called stylistic devices; 6) the splitting of the literary language into separate subsystems called styles; 7) the interrelation between language and thought and 8) the individual manner of an author in making use of language. The term “style” is also applied to the teaching of how to write clearly, simply and emphatically. Style is the correspondence between thought and its expression. To say briefly, style in language is a distinctive linguistic manner of expression.

The meaning of a text does not come into being until it is actively employed in a context of use. This process of activation of a text by relating it to a context of use is called discourse. This contextualization of a text is actually the reader’s reconstruction of the writer’s intended message. It is always possible that the reader infers a different discourse from the text than the one the writer had intended.

Stylistics, sometimes called linguo-stylistics, is a branch of general linguistics. It is concerned with the study of style in language. It explores principles of selection and usage various lexical, grammatical, phonetic and other language media to express thoughts and emotions in different communicative situations. Stylistics can be defined as the analysis of distinctive expression in language and the description of its purpose and effect.

When we encounter a text, we recognize it as belonging to a particular genre, for example, a newspaper article, a menu or an advertisement. We have an idea of what to expect. So if you have become familiar with the stylistic conventions of this genre of texts, you will know that the language of poetry has the following characteristics: its meaning is often ambiguous; it may flout the conventional rules of grammar; it has a peculiar sound structure; it frequently contains indirect references to other texts etc.

There is language stylistics, speech stylistics, linguo-stylistics, stylistics from the author, perception stylistics, literary stylistics, decoding stylistics etc.

Language stylistics explores 1) language subsystems, i.e. functional styles and sublanguages characterized with specific vocabulary, phraseology and syntax; 2) expressive and emotional features of different language media.

Speech stylistics studies separate real texts considering the ways of content transferring according to the language norms and their deviations.

Linguo-stylistics was established by Balli. It compares the common norm of language with special subsystems named functional styles and dialects (in this narrow meaning linguo-stylistics is called functional stylistics) and studies the language elements as the units being able to express and evoke additional emotions and estimation.

The comparative stylistics which is developed intensively takes into consideration stylistic possibilities of two and more languages.

Literary stylistics studies all means of artistic expressiveness, typical for work of literature, the author, trend of literature or the whole age and factors determining the artistic expressiveness.

Both linguo-stylistics and literary stylistics are divided into some levels: lexical, grammatical and phonetic.

Lexical stylistics studies stylistic lexical functions and considers the interaction of direct and indirect meaning. It deals with various compounds of contextual meanings of words, their expressive, emotional and estimating possibilities and also different functional styles they attribute to.

Dialects, terminology, slang, colloquial words and expressions, neologisms, archaisms, barbarisms etc are examined in different conditions of context. The important role in stylistic analysis belongs to the phraseological units and proverbs.

Grammatical stylistics is subdivided into morphological and syntactical. Morphological stylistics considers different grammatical categories attributable to various parts of speech and their stylistic possibilities. Syntactical stylistics explores the expressive possibilities of word order, types of sentences, types of syntactical bond. Figures of speech, which give additional expressiveness, play the important role here. Much attention is paid to different forms of transferring speech: dialogue, direct speech, a stream of consciousness etc.

Phonetic stylistics includes all phenomena of poems and prose sound organization, i.e. rhythm, alliteration, sound imitation, rhyme, assonance etc. Here we can refer the non-standard pronunciation with comic or satirical effect to show the social inequality or to create the local color.

Practical stylistics teaches to speak and treat the language correctly, gives advice how to use the words with well-known meanings. The language should be communicatively pragmatic.

Functional stylistics studies style as the functional variety of the language, especially in belles-lettres text.

The subject of stylistics is the emotional language expression and all expressive means of language, i.e.

the tasks of stylistics:

investigation and selection of special language media among synonymous ways of rendering one and the same idea for reaching desirable effect of the utterance.

the analysis of expressive means in language (for example in phonetics – alliteration, in syntax – inversion).

the determination of functional task, i.e. stylistic function which language means fulfil.

Stylistics is commonly divided into linguo-stylistics and literary stylistics.

Stylistics is closely connected with ancient disciplines:

Study of literature (which examines the content)

Semiotics (which defines the text as the system of signs to be read differently)

Pragmatics (which studies the impact)

Sociolinguistics (the selection of language media depending on the communicative situation).

Вопросы для самоконтроля

1. What does the word “style” presuppose in linguistics?

2. How can you explain the concept of discourse?

3. What is the subject of stylistics?

4. What are the tasks of stylistics?

Список рекомендуемой литературы

1. Гуревич, В.В. English Stylistics. Стилистика английского языка: учебн. пособие /В.В.Гуревич. – М.: Наука, 2008. - 67 с.

2. Солганик, Г.Я. Стилистика текста: учебн. пособие /Г.Я.Солганик. - 6-е изд. - М.: Наука, 2000. - 217 с.

3. Шаховский, В.И. Стилистика английского языка /В.И.Шаховский. – Л.: ЛКИ, 2008. - 235 с.

4. Coupland, N. Towards the Stylistics of Discourse //Styles of Discourse / N.Coupland. - London: Ed. Groom Hel, 1988. - p. 147.

5. Crystal, D., Davy D. Investigating English Style /D.Crystal, D.Davy. - London: Longman, 1969. - p. 94.

6. Galperin, I.R. Stylistics /I.R.Galperin. - M.: Higher School Publishing House, 1981. - 343 c.

Lecture 2: STYLISTIC DEVICES AND EXPRESSIVE MEANS. STYLISTIC FUNCTION

The main concepts of stylistics are:

Tropes – figurative language means in which the word or the word-combination is used in its transferred meaning. They are chiefly lexical and serve for description. The essence of the trope is to compare the traditional usage of the lexical unit with the concept transferred by the same unit while fulfilling the special stylistic function.

Expressive language media – they don’t create images but promote the speech expressiveness and intensify its emotionality by means of specific devices. They are not connected with transferred meaning. They are more predictable than stylistic devices.

Figures of speech – figurative expressive language media. This term is frequently used for stylistic devices that make use of a figurative meaning of the language elements and thus create a vivid image.

Stylistic devices – they can be independent or coincide with the language means. Stylistic device is the intentional and conscious intensification of some typical structural or semantic feature of language unit, including the expressive means.

One and the same stylistic means can be stylistic one in belles-lettres speech and can’t be it in colloquial speech (in one case it amplifies the effect and in the other it doesn’t affect).

Convergence is the simultaneous usage of several stylistic devices.

And to differentiate stylistic devices and expressive means we can say that stylistic device is a model of changing unemotional sentences into pragmatically charged. And expressive means are not connected with the meaning. They serve the emotional and logical intensification of the utterance. They may be phonetic, morphological, word-building, lexical, phraseological and syntactical forms.

Stylistics studies the usage of the expressive means in different speech styles, their potential possibilities as the stylistic devices.

The most powerful expressive means are phonetic (alliteration, assonance, onomatopoeia, rhyme, rhythm etc). The human voice can indicate every nuance of meaning no other means can. Pitch, melody, stress, whispering, a sing-song manner and other ways of using the voice are much more effective than any other means in intensifying an utterance emotionally or logically.

Morphological expressive means is now rather impoverished set of media. But some of them are kept nowadays.

“He shall do it! = I shall make him do it!” (‘shall’ in the second and third person).

Among the word-building means we can point out, for example, diminutive suffixes –y(ie), -let (auntie, streamlet).

At the lexical level there are words with emotive meaning only (interjections – междометия, перебивающий возглас), epithet, metaphor, antonomasia, metonymy, irony, personification, allegory, periphrasis, hyperbole, litotes, words belonging to the layers of slang and vulgar words or to poetic or archaic layers. All kinds of phraseological units possess the property of expressiveness. Proverbs, sayings make speech emphatic.

At the syntactical level there are many constructions which reveal a certain degree of logical or emotional emphasis (inversion, repetition, asyndeton, ellipsis etc).

The stylistic function is the role the language medium plays to transfer expressive information:

- creation of artistic expressiveness;

- creation of inspiration;

- creation of comic effect;

- hyperbole;

- may be descriptive (characterological) for creation of speech characteristic of the hero.

There is no direct correspondence between stylistic means, devices and functions, because the stylistic means are unequal. Inversion, for example, depends on the context and situation and can create inspiration, or vice versa, give ironic, parody meaning. A great number of conjunctions can serve to distinguish logically the elements of the utterance, to create the impression of slow, measured tale or to transfer the anxious questions, suppositions. Hyperbole can be tragic and comic, pathetic and grotesque.

The functional stylistic color (connotation) shouldn’t be mixed with stylistic function. The first one belongs to the language, and the second one – to the text. Unlike neutral words, which only denote a certain notion and thus have only a denotational meaning, their stylistic synonyms usually contain some connotations, i.e. additional components of meaning which express some emotional colouring or evaluation of the object named. In dictionaries functional stylistic and emotional connotations are determined with special marks: colloquial, poetical, slang, ironical, anatomy etc.

Unlike stylistic connotation, stylistic function helps the reader to accentuate the chief idea.

It is also important to distinguish the stylistic function from the stylistic device. We can refer stylistic figures and tropes to stylistic devices. The last ones are syntactical and stylistic figures intensifying emotionality and expressiveness of the utterance by means of unusual syntactical construction: different types of repetition, inversion, parallelism, ellipsis etc. Phonetic stylistic devices are alliteration, assonance, onomatopoeia (sound imitation) and other devices of sound speech organization.

We said that the word “style” is used in various spheres of our life. We also point out the individual style which is frequently identified with the general term “style”. Individual style deals with the peculiarities of a writer’s individual manner of using language means to achieve the effect he desires. Individual style is a unique combination of language units, expressive means and stylistic devices peculiar to a given writer, which makes that writer’s works easily recognizable. The term “style” is widely used in literature to signify literary genre. Thus, we speak of classical style (or style of classicism), realistic style, the style of romanticism and so on. It is applied to various kinds of literary works: the fable, novel, ballad, story, etc. But the general term “style” is a much broader notion.

So, we can resume and define style as a system of interrelated language means which serves to definite aim of communication.

Вопросы для самоконтроля

1. What are the main concepts of stylistics?

2. What is the difference between stylistic devices and expressive means?

3. How can you define the concept of style?

4. What can expressive means be?

5. Characterize phonetic expressive means.

6. What do lexical means serve for?

7. How does stylistic function differ from functional stylistic colour?

8. What is understood by the individual style?

Список рекомендуемой литературы

1. Акимова, Г.Н. Экспрессивные свойства синтаксических структур. /Г.Н. Акимова. – Л.: Ленинградский университет, 1998. – 72 с.

2. Арнольд , И.В. Стилистика. Современный английский язык: учебн. для вузов. /И.В. Арнольд. - 7-е изд. - М.: Высшая школа, 2005. – 383 с.

3. Ильинская, И.С. О языковых и неязыковых стилистических средствах. /И.С. Ильинская. – М.: Высшая школа, 2003. – 63 с.

4. Galperin, I.R. Stylistics. /I.R.Galperin. - M.: Higher School Publishing House, 1981. – 343 с.

5. Screbnev, Y.M. Fundamentals of English Stylistics. /Y.M. Screbnev. - M.: АСТ, 2000. - 224 с.

Lecture 3: STYLISTIC CLASSIFICATION OF THE ENGLISH

VOCABULARY

To speak about functional characteristics of the styles and stylistic devices of language it’s necessary to make clear what is meant by the literary language.

Literary language is a historical category. It exists as a variety of the national language. So, the literary language is that variety of the national language which imposes definite morphological, phonetic, syntactical, lexical, phraseological and stylistic norms. In this connection there are two conflicting tendencies in the process of establishing the norm:

preservation of the already existing norm, sometimes with attempts to re-establish old forms of the lang;

introduction of new norms not yet firmly established.

So, we can define the norm as the invariant of the phonemic, morphological, lexical and syntactical patterns circulating in lang.-in-action at a given period of time.

At every period of time language has its own norms corresponding to the given period of time.

What was happening to the English language throughout its history? How has it changed and why?

Development of the English literary language

The English literary language has had a long peculiar history.

The English language is the result of the integration of the tribal dialects of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes who occupied the British Isles in the 3-d – 5-th centuries. The language was called Anglo-Saxon or Old English. Now, it is a dead language, like Latin or classic Greek. The Old English period lasted approximately until the end of the 12-th century.

During the Middle English period, the English language rapidly progressed towards its present state. By that time it had greatly enlarged its vocabulary by borrowings from Norman-French and other languages.

The New English period is usually dated from the 15-th century. This is the beginning of the English language, spoken and written, at the present time. This period cannot be characterized by uniformity in the language.

In the 16-th century literary English began to flourish with the general growth of culture to which much was contributed by the two universities, Oxford and Cambridge. It was a common interest in classical literature. It was a

tendency to archaisms. An orientation towards the living developing colloquial language.

The 17-th century literary English is characterized by a general tendency to regulation. It was leading to the establishment of the norms of literary English.

By the 18-th century it was the desire to establish language laws. The gap between the literary and colloquial English was widening. The situation of communication has evolved two varieties of language – the spoken and the written.

The most striking difference between the spoken and written languages is in the vocabulary used. There are words and phrases typically colloquial, on the one hand, and typically bookish, on the other.

The spoken language makes use of intensifying words. It is rich in expressive means (interjections, words with strong emotive meaning, unfinished sentences are also typical of the spoken language).

In the written language most of the connecting words are used only there (nevertheless, therefore, furthermore, moreover). And written language is rich in complicated sentences.

The 19-th century is characterized by the purification of the language from vulgarisms and new words. The tendency to protest against innovation. At this time colloquial words and expressions created by the people began to pour into literary English. And a more or less firmly established differentiation of styles began. By this period the shaping of the newspaper style, the publicist style, the style of scientific prose and the official style have been completed. And belles-lettres prose called for a system of expressive means and stylistic devices.

Functional styles of language have shaped themselves within the literary form of the English language. The standard English language was divided into the literary language and the colloquial language.

The word stock of a language may be represented as a definite system.

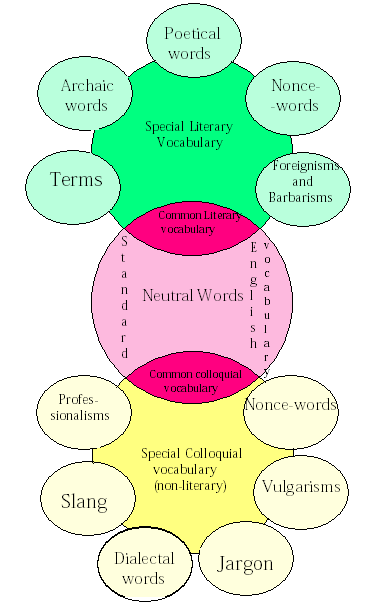

According to the diagram by Galperin I.R. we may represent the whole of the word stock of the English language as being divided into three main layers: the l i t e r a r y l a y e r, the n e u t r a l l a y e r and the c o l l o q u i a l l a y e r. The literary and the colloquial layers contain a number of subgroups. The aspect of the literary layer is its bookish character, this makes the layer more or less stable. The aspect of the colloquial layer is its spoken character. It makes it unstable. The aspect of the neutral layer is its universal character. It can be employed in all styles of language and in all spheres of human activity. It makes the layer the most stable of all.

The literary vocabulary consists of the following groups of words: 1. common literary; 2. terms; 3. poetic words; 4. archaic words; 5. foreignisms and barbarisms; 6. nonce-words.

The colloquial vocabulary falls into the following groups: 1. common colloquial words; 2. slang; 3. jargonisms; 4. professionalisms; 5. dialectal words; 6. vulgarisms; 7. colloquial coinages (nonce-words).

The common literary, neutral and common colloquial words are grouped under the term s t a n d a r d E n g l i s h v o c a b u l a r y. Other groups in the literary layer are defined as special literary vocabulary and those in the colloquial layer are defined as special colloquial (non-literary) vocabulary.

Вопросы для самоконтроля

1. What is the literary language?

2. How can we define the norm of the language?

3. When did differentiation of styles begin?

4. What layers is the English language divided?

5. Characterize the diagram

Список рекомендуемой литературы

1. Арнольд, И.В. Стилистика. Современный английский язык: учебн. для вузов. /И.В. Арнольд. - 7-е изд. - М.: Высшая школа, 2005. – 383 с.

2. Шаховский, В.И. Стилистика английского языка. /В.И. Шаховский. – Л.: ЛКИ, 2008. – 235 с.

3. Galperin, I.R. Stylistics. /I.R. Galperin. - M.: Higher School Publishing House, 1981. – 343 c.

Lecture 4: NEUTRAL, COMMON LITERARY AND COMMON COLLOQUIAL VOCABULARY

Stylistic differences of any kind can be expressed by various language means: phonetic, lexical or grammatical. One of the most vivid means is, naturally, the choice of vocabulary. Compare three layers of the English language:

Neutral Colloquial Literary

child kid infant/offspring

father daddy parent/ancestor

leave/go away be off/get out/ retire/withdraw

get away

continue go on proceed

begin/start get started/ commence

come on

Neutral words form the main part of word stock. These words are used in all functional styles.

Stylistically neutral words usually constitute the main member in a group of synonyms, the so-called synonymic dominant (синонимическая доминанта). They are not emotionally coloured and have no additional evaluating elements; such are the words child, father, begin, leave/go away, continue in the examples above.

Common literary words are chiefly used in rhetoric, written speech.

Common colloquial words are literary standard words plus some familiar words. They represent casual speech, unofficial communication. Phrasal verbs often have the mark colloq.

Unlike neutral words (synonymic dominants), which only denote (обозначают) a certain notion and thus have only a denotation meaning (денотативное значение, обозначение некоторого понятия), their stylistic synonyms usually contain some connotations (коннотации), i.e. additional components of meaning which express some emotional colouring or evaluation (оценка) of the object named; these additional components may also be simply signs of a particular functional style of speech. For example:

An endearing connotation (ласкат.) – e.g. in the words kid, daddy (as different from the neutral words child, father); approving evaluation (одобрительная оценка) – e.g. in the word renowned (a renowned poet = прославленный; on the other hand, its synonyms like well-known, famous are neutral in this respect (have no connotations).

It should be noted that we do not include into the stylistically coloured vocabulary words that directly express some positive or negative evaluation of an object – хороший, плохой, красивый, некрасивый, прекрасный, уродливый;good, bad, pretty, ugly. Here the evaluation expressed makes up their denotation meaning proper, but not an additional connotation. In the sentence Don’t read this bad book the negative evaluation is expressed directly (by the denotation meaning of the adjective bad), whereas in Don’t read this trash the evaluation is expressed by the derogatory colouring of the noun trash – in other words, it is present here only as a connotation; thus, words like trash, rot, stuff (=”something worthless, bad”) are stylistically marked (стилистически маркированы, т.е. обладают определенной стилистической окраской), while the word bad is stylistically unmarked (стилистически не маркировано, нейтрально).

Apart from that, the stylistic connotation of a word may be just a sign of a certain functional style to which the word belongs, without carrying any emotional or evaluative element. Thus, sentence like It’s cool (Это круто) contains not only a high positive evaluation (in the same way as the stylistically neutral variant It is very good), but also a stylistic connotation which shows that it belongs to the familiar-colloquial style (фамильярно-разговорный стиль), or even to slang.

Вопросы для самоконтроля

1. How is standard English vocabulary represented?

2. Characterize neutral, common literary and common colloquial vocabulary.

3. What is the difference between them?

4. Where do common colloquial words mainly occur?

5. Speak about the connotation and denotation meanings.

Список рекомендуемой литературы

1. Арнольд, И.В. Стилистика. Современный английский язык: учебн. для вузов. /И.В. Арнольд. - 7-е изд. - М.: Высшая школа, 2005. – 383 с.

2. Гуревич, В.В. English Stylistics. Стилистика английского языка: учебн. пособие. /В.В. Гуревич. - М.: Наука, 2008. – 67 с.

3. Galperin, I.R. Stylistics. /I.R. Galperin. - M.: Higher School Publishing House, 1981. – 343 c.

4. Screbnev, Y.M. Fundamentals of English Stylistics. /Y.M. Screbnev. - M.: АСТ, 2000. – 224 с.

Lecture 5: SPECIAL LITERARY VOCABULARY (книжно-литературная лексика)

Special literary vocabulary is marked with ‘lit’ or ‘fml’ – formal, highly literary, bookish words. It includes terms, archaic words, nonce-words, foreignisms and barbarisms.

A formal (bookish) style is required in situations of official or restrained relations between the interlocutors, who try to avoid any personal and emotional colouring or familiarity, and at the same time to achieve clarity of expression. This style is used in various genres of speech, such as in official documents, scientific works, publicist works or public speeches, etc. Special literary vocabulary is represented with several groups.

Terms

A term is generally very easily coined and easily accepted. Terms are generally associated with a definite branch of science. Terms are characterized by a tendency to be monosemantic and therefore easily call the required concept. They belong to the scientific style. They may as well appear in all other existing styles. But their function in this case changes. They no longer refer to a given notion or concept, they indicate the technical peculiarities of the subject, make some reference to the occupation of a character whose language contains special words and sometimes special terminology suggests that the author is showing off his erudition.

When terms lose their qualities as terms and pass into the common literary vocabulary, this process may be called “de-terminization”. Such words as radio, television, and the like have long been in common use and their terminological character is no longer evident.

Poetic and highly literary words

They are marked with ‘poet’. Poetic words are used primarily in poetry, they belong to a definite style of language and perform in it their direct function - to evoke emotive meanings.

Poetic language has special means of communication, i.e. rhythmical arrangement, some syntactical peculiarities and a certain number of special words.

Poetic words in the English language do not present a homogeneous group: they include archaic words such as naught=nothing, woe=grief, thee=you. The use of a contracted form of a word instead of the full one is very common in English poetry (morn=morning, even=evening, oft=often). Sometimes we may see an expanded form of a word (vasty=vast, steepy=steep). But such devices are generally avoided by modern English poets. Due to poeticisms poetical language is sometimes not very understandable.

Archaic words

Besides the vocabulary that is in current use, we also find archaic words, which belong to some previous stage of language development but can still be found in works of fiction (especially in the works of Shakespeare, Chaucer, Swift or other classical authors). Cf. the archaic words Behold!=Look!, Wither are you going?=Where are you going to? whilst-while, etc.

We may divide them into three groups:

Obsolescent – words which become rarely used; to this category we may refer morphological forms belonging to the earlier stages in the development of the language, (the pronouns thou, thee, thy, thine; the ending –(e)th instead of –(e)s – he maketh); many French borrowings ( a palfrey=a small horse; garniture=furniture);

Obsolete – words that have already gone completely out of use but are still recognized by the English speaking community (methinks=I think, it seems to me; nay=no);

Archaic proper – words which are no longer recognizable in modern English, that were in use in Old English, which have either dropped out of the language entirely or have changed in their appearance so much that they have become unrecognizable (troth=faith).

The vocabulary that has gone out of use also includes the so called ‘historisms’ – words which reflect some phenomena belonging to the past times, e.g. knight (рыцарь), archer (лучник); cf. also Russian historisms like городничий, городовой, бояре. Historical terms never disappear from the language, they remain as terms referring to definite stages in the development of society. Historical words have no synonyms, whereas archaic words have been replaced by modern synonyms.

The main function of archaisms in works of fiction is to reflect the life of the heroes of historical novels, to depict “local and time colour”. They create a realistic background to historical novels. Archaisms make the reader “look into the epoch, feel it”.

Archaic words and phrases are found in other styles, frequently in the style of official documents. In this case they are terminological in character. Among the archaic elements the following may be mentioned: hereby, hereinafternamed.

Archaic words are sometimes used for satirical purposes and to create an elevated effect.

Barbarisms and Foreign words

Comparatively new borrowings from other languages, which are not yet completely assimilated in the language (phonetically or grammatically), but have been already become facts of the English language, are stylistically marked as ‘barbarisms’. Most of them have corresponding English synonyms, e.g. de facto=(in point of fact), status quo=(the existing state of things). Barbarisms are generally given in the dictionary.

Foreign words do not belong to the English vocabulary. They are not registered by English dictionaries. There are foreign words in the English vocabulary which fulfil a terminological function. Such words as solo, tenor and the like are terms. They have no synonyms.

Both foreign words and barbarisms are widely used in various styles of language, especially, in the style of belles-lettres and the publicist style with various aims, one of their function is to supply local color.

Literary coinages (including nonce-words)

According to the function they are divided into:

terminological coinages or neologisms;

stylistic coinages or neologisms;

The first ones designate new concepts resulting from the development of science.

The second type is created to be a more expressive means of communicating the idea.

According to the formal-semantic meaning their classification is following:

proper neologisms ( both a new form and a new meaning)

to telecommute

They are similar to terminological coinages.

transnomination (new form but an old meaning)

big C – cancer, I am burned out – tired/exhausted

They refer to synonyms and may be regarded as stylistic coinages.

semantic innovations (old form but a new meaning)

sophisticated – раньше “умудренный опытом”, теперь

sophisticated computer – прогрессивный

They promote polysemy in the language.

nonce-words (окказионализмы).

They appear for particular occasion. They are not included into the dictionaries. Their main purpose is functional disposability. They are often formed by means of conversion.

I wifed in Texas, mother-in-lawed, uncled, aunted, cousined …

Nonce-words are not reproduced in speech, they are repeated. They are individual formations and have their own author. They are quite expressive, humorous and are created according to the existing word-formation (balconyful – балкон, полный людей).

Nonce-words can be:

system – which appear according to word-formation models; they can become neologisms if they occur many times.

unsystem– those are formally or semantically distorted (“incorrect words”), based on deformation. Винни Пух: It’s a missage (когда в горшке вместо меда обнаруживает message).

Вопросы для самоконтроля

1. What are the main subgroups of special literary words?

2 .What do you know of terms, their structure, meaning, functions?

3. What are the fields of application of archaic words and forms?

4. What is the difference between barbarisms and foreign words?

5. How can literary coinages be classified?

Список рекомендуемой литературы

1. Арнольд, И.В. Стилистика. Современный английский язык: учебн. для вузов. /И.В. Арнольд. - 7-е изд. - М.: Высшая школа, 2005. – 383 с.

2. Гуревич, В.В. English Stylistics. Стилистика английского языка: учебн. пособие. /В.В. Гуревич. – М.: Наука, 2008. – 67 с.

3. Galperin, I.R. Stylistics. /I.R. Galperin. - M.: Higher School Publishing House, 1981. – 343 c.

Lecture 6: SPECIAL COLLOQUIAL VOCABULARY

Standard colloquial style - the style of informal, friendly oral communication. Its vocabulary is usually lower than that of the formal or neutral styles, it is often emotionally coloured by connotations (daddy, kid).

Colloquial speech is characterized by the frequent use of words ,with a broad meaning (широкозначные слова): speakers use a small group of words in quite different meanings, whereas in a formal style every word is to be used in a specific and clear meaning. Compare the different uses of the verb “get”:

I got (=received) a letter today; Where did you get (=buy) those shoes&; We don’t get (=have) much rain here in summer; I got (=caught) flu’ last month; We got (=took) the six[-o’clock train from London; I got into (=entered) the house easily; Where has my pen got to (=disappeared)?; We got (=arrived) home late; Get (=put) your hat on!; I can’t get (=fit) into my old jeans; Get (=throw ) the cat out of the house!; I’ll get (=punish) you, just you wait!; We got (=passed) through the customs without any checking; I’ve got up to (=reached) the last chapter of the book; I’ll get (=fetch) the children from school; It’s getting (=becoming) dark; He got (=was) robbed in the street at night; I got (=caused) him to help me with the work; I got the radio working at last (=brought it to the state of working); Will you get (=give, bring) the children their supper tonight?; I didn’t get (=hear) what you said; You got (=understood) my answer wrong; I wanted to speak to the director, but only got (=managed to speak) to his secretary; Will you get (=answer) the phone?; Can you get (=tune in) to London on your radio?

There are phrases and constructions typical of colloquial type: What’s up? (=what has happened?); No problem! (=This can easily be done), etc.

In grammar: a) the use of shortened variants of word-forms (isn’t, can’t; there’s; I’d say; Yaa) b) the use of elliptical (incomplete) sentences (I did; Like it? May I?).

The syntax is characterized by the preferable use of simple sentences. Note the neutral style in the following extract:

When I saw him there, I asked him, ‘Where are you going?’, but he started running away from me. I followed him. When he turned round the corner, I also turned round it after him, but then noticed that he was not there. I could not imagine where he was…

and the same extract in its colloquial version:

I saw him there, I say ‘Where’ye going?’ He runs off, I run after him. He turns the corner, me too. He isn’t there. Where’s he now? I can’t think… (note also the rather frequent change from the Past tense to the Present, in addition to the absence of conjunctions or other syntactic means of connection).

Non-standard (familiar-colloquial) style of speech is mostly represented by a special vocabulary. Here we find emotionally coloured words (general slang), low-colloquial vocabulary and slang words, rude and vulgar vocabulary (taboo), jargons, professional (special) slang, dialectal words.

General slang (sl.infml) – are the words and expressions with ironic, rudish shade. They make the speech informal (cool - клевый, pan – физиономия, get hyper – выходить из себя, don’t get hyper – не заводись, cabbage – капуста, бабло).

General slang:1) makes speech specific and fresh;

2) promotes short distance between the speakers;

3) establishes conformism;

4) demonstrates denial of common valuables (to die – to check out, to pop off, to sling one’s hook, to go west, to snuff out, to kick the bucket).

As we said general slang should be distinguished from low-colloquial words. General slang is characterized by its expressiveness, informality and ironic or rudish shade. But low-colloquial words have rude connotation, they are not used in respectable conversation (bitch, bastard) . From the other hand, you should separate them from rude literary words (moron – идиот, слабоумный).

The meaning of the term ‘slang’ is given in many dictionaries.

Webster’s “New World Dictionary of the American Language” gives the following meanings of the term:

“1. originally, the specialized vocabulary and idioms of criminals, tramps, etc. the purpose of which was to disguise from outsiders the meaning of what was said; now usually called cant. 2. the specialized vocabulary and idioms of those in the same work, way of life, etc.; now usually called shoptalk, argot, jargon. 3. colloquial language that is outside of conventional or standard usage and consists of both coined words and those with new or extended meanings; slang develops from the attempt to find fresh and vigorous, colourful, pungent or humorous expression, and generally either passes into disuse or comes to have a more formal status.”

The “New Oxford English Dictionary” defines slang as follows:

“a) the special vocabulary used by any set of persons of a low or disreputable character; language of a low and vulgar type; b) the cant or jargon of a certain class or period; c) language of a highly colloquial type considered as below the level of standard educated speech, and consisting either of new words or of current words employed in some special sense.”

What can we refer to slang?

The following stylistic layers are generally marked as slang:

Words which may be classed as thieves’ cant, or the jargons of other social groups and professions, like dirt=money, to dance=to hang.

Colloquial words and phrases of professional or dialectal direction (to have a hunch – предчувствовать; fishy – ‘suspicious’)

Figurative words and phrases (Scrooge – a mean person, shark –‘a pickpocket’)

Words derived by means of conversion (the noun ‘agent’ is considered neutral, because it has no stylistic notation, and the verb ‘to agent’ –‘разбойничать’ is included in one of the American dictionaries of slang; ‘ancient’ (adj.) – ‘древний’, ‘античный’, ‘ancient’ (n.) – ‘старикашка’, ‘старая развалина’).

Abbreviations (rep – reputation, cig – cigarette, ad – advertisement, flu – influenza).

Set expressions which are generally used in colloquial speech (to go in for)

Improprieties of a morphological and syntactical character (I says), double negatives as ‘I don’t know nothing’.

Any new coinage that has not gained recognition and has not yet been received into standard English.

It is suggested that the term “slang” should be used for those forms of the English language which are either mispronounced or distorted in some way phonetically, morphologically or lexically.

Slang is nothing but a deviation from the established norm at the level of the vocabulary of the language.

What about the purpose of the slang? It is well written in “A Historical Dictionary of American Slang”:

“Sometimes slang is used to escape the dull familiarity of standard words, to suggest an escape from the established routine of everyday life. When slang is used, our life seems a little fresher and a little more personal. Also, as at all levels of speech, slang is sometimes used for the pure joy of making sounds, or even for a need to attract attention by making noise.

But more important … is the slang’s reflection of the personality, the outward, clearly visible characteristics of the speaker.”

We said, that the term “slang” is broad and there are many kinds of slang: cockney, commercial, military, theatrical, parliamentary and others and there is also a standard slang, the slang that is common to all people who receive standard in their writing and speech and also use an informal language which, in fact, is no language but merely a way of speaking, using special words and phrases in some special sense.

What causes the nature of slang?

Personality and surroundings (social or occupational) are the two chief factors determining the nature of slang.

I’d like to show you one more episode from the story by O. Henry “By courier”. O. Henry opposes neutral and common literary words to special colloquial words and slang for a definite stylistic purpose. He distorts a message by translating the literary vocabulary of one speaker into the non-literary vocabulary of another (discard – отбрасывать, отказываться от чего-либо; moosehunting – охота на американского лося).

“Tell her I am on my way to the station, to leave for San Francisco, where I shall join that Alaska moosehunting expedition. Tell her that, since she has commanded me neither to speak nor to write to her, I take this means of making one last appeal to her sense of justice, for the sake of what has been. Tell her that to condemn and discard one who has not deserved such treatment, without giving him her reason or a chance to explain is contrary to her nature as I believe it to be.”

This message was delivered in the following manner:

“He told me to tell yer he’s got his collars and cuffs in dat grip for a scool clean out to ‘Frisco. Den he’s goin’ to shoot snowbirds in de Klondike. He says yer told him to send ‘round no more pink notes nor come hangin’ over de garden gate, and he takes dis mean (sending the boy to speak for him) of putting yer wise. He says yer referred to him like a has-been, and never give him no chance to kick at de decision. He says yer swilled him and never said why.”

The contrast between what is standard English and what is crude, broken non-literary or uneducated American English has been achieved by means of setting the common literary vocabulary and also the syntactical design of the original message against jargonisms, slang and all kinds of distortions of forms, phonetic, morphological, lexical and syntactical.

Jargonisms

It is a special slang. It is a recognized term for a group of words whose aim is to preserve secrecy within one or another social group.

They may be defined as a code within a code, i.e. special meanings of words that are imposed on the recognized code – the dictionary meaning of the words (‘loaf’ means ‘head’; ‘lexer’ – a student preparing for a law course (лат. ‘lex’ – закон)

Jargonisms are social in character. They are not regional. In England and in the USA almost any social group of people has its own jargon. The following jargons are well known in the English language: the jargon of thieves, the jargon of jazz people, of the army, the jargon of sportsmen and so on.

The various jargons remain a foreign language to the outsiders of any particular social group. Slang, contrary to jargon, needs no translation. It is not a secret code.

Jargonisms do not always remain the possession of a given social group. Some of them migrate into other social strata and sometimes become recognized in the literary language of the nation.

But as the general slang differs from low-colloquial, the common jargons differ from special professional jargons.

We must remark that both slang and the various jargons of Great Britain differ much more from those of America than the literary language in the two countries does. American slang on the whole remains a foreign language to the Englishman.

Jargonisms, like slang and other groups of the non-literary layer, do not always remain on the outskirts of the literary language. Many words have entered the standard vocabulary. Thus the words kid, fun, humbug, formely slang words or jargonisms, are now considered common colloquial. They may be said to be dejargonized.

Professionalisms

Professionalisms are the words used in a definite trade, profession by people connected by common interests both at work and at home. They commonly designate some working process. Professionalisms are correlated to terms.

Terms are coined to nominate new concepts that appear in the process of technical progress and the development of science. Professional words name anew already-existing concepts, tools or instruments, and have the typical properties of a special code.

Professionalisms are special words in the non-literary layer of the English vocabulary, whereas terms are a specialized group belonging to the literary layer of words.

Terms are easily decoded and enter the neutral stratum of the vocabulary. Professionalisms generally remain in circulation within a definite community, they are linked to a common occupation and common social interests.

The semantic structure of the term is easily understood. The semantic structure of a professionalism is often dimmed.

But, like terms, professionalisms do not allow any polysemy, they are monosemantic.

Here are some professionalisms used in different trades: ‘tin-fish’ –‘submarine’; ‘block-buster’ – a bomb especially designed to destroy blocks of big buildings’

Professionalisms should not be mixed up with jargonisms. Like slang words, professionalisms do not aim at secrecy. They fulfil a socially useful function in communication, facilitating a quick and adequate grasp of the message.

There are certain fields of human activity which gain a nation-wide interest and popularity, in Great Britain, for example, it concerns sports and games. And professionalisms are wide-spread in this sphere.

Professionalisms are used in emotive prose to depict the natural speech of a character. The skilful use of a professional word will show not only the vocation of a character, but also his education, breeding, environment and sometimes even his psychology.

Dialectal Words

Dialectal words are those which in the process of integration of the English national language remained beyond its literary boundaries, and their use is

generally referred to a definite locality. Such words are connected with agriculture,

horses, cattle and sport.

There is sometimes a difficulty in distinguishing dialectal words from colloquial words. Some dialectal words have become so familiar in standard colloquial English that they are universally accepted as recognized units of the standard colloquial English. To these words belong ‘lass’ meaning ‘a girl or a beloved girl’ and the corresponding ‘lad’, ‘a boy or a young man’.

To the dialects are usually referred the non-standard varieties of English used on the territory of Great Britain, while the word variants (varieties) refers to the use of English outside this territory, e.g. the English language of the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, etc.