- •I. Теоретична фонетика

- •1. Розвиток фонологічної теорії у xXстолітті.

- •2. Система фонем і фонематичних опозицій сучасної англійської мови.

- •3. Інтонаційна система сучасної англійської мови. Структура інтонаційних одиниць. Функції інтонації

- •4. Сучасний стандарт англійської мови. Соціолінгвістичні фактори варіантності вимови.

- •5. Фоностилістика. Інтонаційні стилі мовлення.

- •Іі. Історія англійської мови

- •1. Характерні риси германських мов.

- •Фонетичні процеси в давньоанглійській та їх залишки в сучасній англійській мові.

- •3. Розвиток іменних граматичних категорій в англійській мові.

- •Історичний розвиток аналітичних форм дієслова в англійській мові.

- •5. Лінгвістичні наслідки скандинавського та норманського завоювань. Порівняння скандинавського та французького впливів. Розвиток національної літературної англійської мови.

- •Розвиток національної літературної англійської мови.

- •6. Фонологічні процеси у середньо- та ранньоновоанглійському періодах й формування системи фонем сучасної англійської мови.

- •7. Писемні пам'ятки давньо-, середньо- та новоанглійського періодів.

- •Ііі. Лексикологія

- •1. Етимологічний склад англійської мови. Типи запозичень.

- •2. Словотворення в англійській мові. Основні та другорядні типи словотворення.

- •3. Проблеми семасіології англійської мови. Типи значення слова. Полісемія.

- •4. Системна організація словникового складу англійської мови. Синонімія та антонімія.

- •5. Проблема визначення фразеологічних одиниць у сучасній англійській мові та їх класифікація.

- •IV. Теоретична граматика

- •1. Загальна характеристика граматичного складу сучасної англійської мови

- •2. Лексичні та граматичні аспекти англійського слова. Проблема визначення частин мови в сучасній лінгвістиці

- •3. Граматичні властивості та граматичні категорії іменника в сучасній англійській мові

- •4. Граматичні властивості та граматичні категорії дієлова в сучасній англійській мові

- •5. Сучасні підходи до вивчення речення та тексту: лінгвістика тексту, прагмалінгвістика, дискурсиний аналіз

- •V. Стилістика

- •1. Основні поняття стилістки англійської мови та інтерпретація художнього тексту

- •2. Стилістичне значення та його види. Силістична диференціація словникового складу сучасної англійської мови

- •3. Зображально-виражальні засоби та стилістичні прийоми сучасної англійської мови

- •4. Поняття функціонального стилю. Класифікація функціональних стилів в англійській мові.

- •5. Текст як категорія лінгвостилістики. Основні антропоцентри художнього тексту (образ автора, образ персонажа, образ читача)

3. Розвиток іменних граматичних категорій в англійській мові.

Inflected parts of speech possessed certain grammatical categories, which are usually subdivided into nominal categories, found in nominal parts of speech (the noun, the adjective, the pronoun, the numeral) and verbal categories found mainly in the finite verb.

There were 5 nominal grammatical categories in OE: number, case, gender, degrees of comparison, and the category of definiteness/indefiniteness.

Gender

in Old English the divergence between the grammar gender and the sex, occurred in some cases . For example: the noun – woman (OE wifman) was masculine gender; maiden (OE mеgden) – neutral gender. Proceeding from the point that the grammar gender not often corresponds to natural gender(sex), a great number of scientists confess that the form, but not the meaning is a decisive factor of the considering problem that however is not relevant to Modern English. By the 11th century, the role of grammatical gender in Old English was beginning to decline.

The Middle English of the 13th century was in transition to the loss of a gender system, as indicated by the increasing use of the gender-neutral identifier þe (the).The loss of gender classes was part of a general decay of inflectional endings and declensional classes by the end of the 14th century.Gender loss began in the north of England; the south-east and the south-west Midlands were the most linguistically conservative regions, and Kent retained traces of gender in the 1340s.Late 14th-century London English had almost completed the shift away from grammatical gender, and Modern English retains no morphological agreement of words with grammatical gender.

But in Modern English morphological markers of the category of gender appeared to be mostly lost, that is why the meaning of gender in English is transferred by: a) lexical meanings of the word: masculine gender – man, boy ; feminine gender – woman, girl ; neutral gender – table, house ; b) personal pronouns – he, she, it ; c) in the word’s structure with the help of suffixes – ess, - ine, -er : an actress , a heroine, a widower, a tigress ; d) compound nouns: a woman-doctor; a he-wolf; a she-wolf . As in many other languages the category of gender in English is strongly tied with the category of “ animate – inanimate ” and the category of inanimate practically corresponds with the neutral gender. From this naturally comes the conclusion that in Modern English words are classified according to “gender” through the things with which they correlate.

In OE The category of number consisted of two members: singular and plural. they were well distinguished formally in all the declensions.

In ME Number proved to be the most stable of the nominal categories. The noun preserved the formal distinction of two numbers through all the historical periods. In Late ME the ending –es was the prevalent marker of nouns in the pl. It underwent several phonetic changes: the voicing of fricatives and the loss of unstressed vowels in final syllables:

1) after a voiced consonant or a vowel, e.g. ME stones [΄sto:nəs] > [΄stounəz] > [΄stounz], NE stones;

2) after a voiceless consonant, e.g. ME bookes [΄bo:kəs] > [bu:ks] > [buks], NE books;

3) after sibilants and affricates [s, z, ∫, t∫, dз] ME dishes [΄di∫əs] > [΄di∫iz], NE dishes.

The ME pl ending –en, used as a variant marker with some nouns lost its former productivity, so that in Standard Mod E it is found only in oxen, brethren, and children. The small group of ME nouns with homonymous forms of number has been further reduced to three exceptions in Mod E: deer, sheep, and swine. The group of former root-stems has survived also only as exceptions: man, tooth and the like.

In OE the noun had four cases: Nominative, Genitive, Dative and Accusative (sometimes instrumental).

The Nominative case indicated the subject of the sentence, for example: se cyning means 'the king'. It was also used for direct address. Adjectives in the predicate (qualifying a noun on the other side of 'to be') were also in the nominative.

The Accusative case indicated the direct object of the sentence, for example: Æþelbald lufode þone cyning means "Æþelbald loved the king", where Æþelbald is the subject and the king is the object. Already the accusative had begun to merge with the nominative; it was never distinguished in the plural, or in a neuter noun.

The Genitive case indicated possession, for example: the þæs cyninges scip is "the ship of the king" or "the king's ship". It also indicated partitive nouns.

The Dative case indicated the indirect object of the sentence; To/for whom the object was meant. For example: hringas þæm cyninge means "rings for the king" or "rings to the king". Here, the word cyning is its Dative form: cyninge. There were also several verbs that took direct objects in the dative.

The Instrumental case indicated an instrument used to achieve something, for example: lifde sweorde, "he lived by the sword", where sweorde is the instrumental form of sweord. During the Old English period, the instrumental was falling out of use, having largely merged with the Dative. Only pronouns and strong adjectives retained separate forms for the instrumental

In ME The grammatical category of Case was preserved but underwent profound changes. The number of cases in the noun paradigm was reduced from four to two in Late ME. In the strong declension the Dat. was sometimes marked by -e in the Southern dialects; the form without the ending soon prevailed in all areas, and three OE cases, Nom., Acc. and Dat. fell together. Henceforth they are called the Common case in present-day English. The Gen. case was kept separate from the other forms, with more explicit formal distinctions in the singular than in the plural. In the 14th c. the ending -es of the Gen. sg had become almost universal, there being only several exceptions – nouns which were preferably used in the uninflected form (some proper names, names of relationship). In the pl the Gen. case had no special marker – it was not distinguished from the Comm. case pl or from the Gen. sg. Several nouns with a weak plural form in -en or with a vowel interchange, such as oxen or men, added the marker of the Gen. case -es to these forms: oxenes, mennes. In the 17th and 18th c. a new graphic marker of the Gen. case came into use: the apostrophe.

In Modern ENGLISH This category is expressed by the opposition of the form -’s, usually called the possessive case, or more traditionally, the genitive case, to the unfeatured form of the noun, usually called the common case. The apostrophized -s serves to distinguish in writing the singular noun in the possessive case from the plural noun in the common case: the man s duty, the President s decision. The possessive of the bulk of plural nouns remains phonetically unexpressed: the few exceptions concern only some of the irregular plurals: the actresses ‘dresses, the mates ‘help, the children s room.

Degrees of comparison

Most OE adjectives distinguished between three degrees of comparison: positive, comparative and superlative. The regular means used to form the comparative and the superlative from the positive were the suffixes –ra and –est/-ost. (earm (poor) - earmra - earmost ; blæc (black) - blæcra - blacost ). Many adjectives changed the root vowel - another example of the Germanic ablaut:

eald (old) - ieldra - ieldest strong - strengra - strengest long - lengra - lengest geong (young) - gingra - gingest

The most widespread and widely used adjectives always had their degrees formed from another stem, which is called "suppletive" in linguistics. Many of them are still seen in today's English:

gód (good) - betera - betst (or sélra - sélest) yfel (bad) - wiersa - wierest micel (much) - mára - máést

Double comparison was common in Middle English and Early Modern English and occurs in Shakespeare’s dramas as well as in King James Bible. Today it has disappeared from written English, but can still beheard in spoken English. The same is true for hybrid forms such as worser and bestest.

The periphrastic forms steadily became more frequent after the fourteenth century until, by the end of the sixteenth century, they were as frequent as they are today. In Early Modern English the choice of comparison was freer than today and forms like beautifuller and more near were rather frequent. There is evidence that the endings were considered colloquial and more and most formal, but, in general, any adjective could be compared either way: Shakespeare writes sweetest as well as most sweet.

Inflected forms of polysyllabic adjectives such as notorious, perfect, learned, shameful and careful also occurred.

Modern English. The basic principle is that most monosyllabic adjectives are compared with endings. When it comes to disyllabic adjectives, especially the ones with certain endings, they are compared synthetically.

Сategory of definiteness/indefiniteness.

Articles are actually just a special kind of adjective. They are adjectives which show the definiteness of the noun being referred to. In Modern English, we have several articles:

The definite article (in Modern English "the") shows that a substantive is a particular noun that the listener should recognize

The indefinite (in Modern English "a","an", or "some" for plural) shows that a substantive is not a specific noun that the listener shoulder recognize

The negative article (in Modern English "no") shows that there is none of the substantive

In Old English, their definite article was also used as a demonstrative adjective and as a demonstrative pronoun, equivalent to Modern English "that" or "that one".

Also, in Old English they generally had no indefinite article (although occasionally their word for "one" - ān could be translated into Modern English as "a" or "an"). So in speaking Old English, a noun with no article at all would often be the equivalent to a noun with an indefinite article in Modern English, for example hūs - "a house", and dēor - "an animal".

There were several words that could be used to translate the negative article "no" in Old English:

nān - "not (even) one"

nǣniġ - "not any (at all)"

They both followed the normal strong adjectival declension and agreed with the nouns they modified.

Because articles are a kind of adjective, they were declined in agreement with whatever noun they modified.

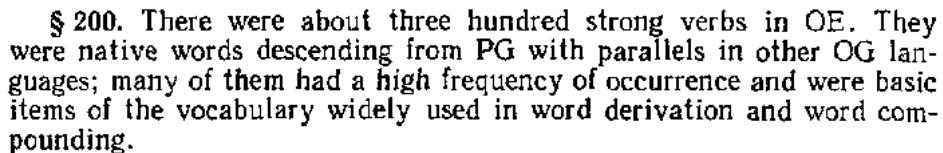

4. Сильні, слабкі, претерито-презентні та аномальні дієслова у давньо-англійській мові та їх співвідношення з правильними, неправильними та модальними дієсловами сучасної англійської мови. Історичний розвиток аналітичних форм дієслова в англійській мові. Історичний розвиток неособових форм дієслова в англійській мові.

The

modern notions of irregular/regular verbs correspond to notions of

strong/weak verbs (differentiated by the form-building features of

past tesne and participle two) in historical linguistics

respectively. The verbal system already in OE period had such

categories: number (sg/pl), person (1st,

2nd,

3d Sg, no person distinctions in Pl), mood (indicative, subjunctive,

imperative ), tense (present, past and the future tense only begins

to develop in this period), the category of voice was not yet

established, however Passive voice meaning was rendered by free word

combinations. (Also:

3 impersonal verb forms if infinitive, participle 1, participle. The

OE verbs had 4 main forms: infinitive, past singular, past plural and

participle 2.

Let

me dwell upon the strong verbs first. Their means of form-building –

ablaut/gradation (root vowel variation) is very old phenomenon shared

by all the IE languages (стелю/стол).

However only in the Germanic languages it turned out to be a regular

morphological mean/tool. Once having been dominating form-building

means, more productive than suffixation (which was presented in the

weak verbs) the influence of it (and therefore the entire

strong-verbs system) had been depleting trough the pace of time,

forced out by weak-verbs form-building means, that probably allows

one to affirm that this tool is more of the archaic nature. The core

of ablaut is the vowel gradation that could be described with a

formula e – o – zero (grade), that for non-Germanic languages

(for instance in Greek leipo - leloipa – elipon: to leave). In the

Germanic lang-s because of the Germanic fracture (IE e corresponds to

> Germanic i) and general correspondence of IE short o to short PG

(Proto-Germanic/Common Germanic ) a, this formula changes into i –

a – zero. However in terms of the English lang, this ablaut system

became vague and unstable already in OE period. One can just compare

first class (7 classes of strong verbs, differentiated due to the

type of vowel gradation) verb reisan – rais –risu, risans (in

Gothic, in this lang in the Bible of IV this verb system is

well-presented) and OE verb risan – ras – rison – risen and see

that this PF ablaut formula is ambiguous (due to the correspondence

of OE long a to PG diphthong ai). The same goes with the second verb

class, for instance (Gt iu – OE eo, Gt au – ea: Gt kiusan –

kaus OE ceosan – ceas) and with the whole verb system (with all the

classes) that is more complex that that of the Gothic lang. In OE

verb the quantitative ablaut preserves in the VI class of strong

verbs (faran – for – foron – faren). The strong verbs VII class

complicates: form-building either with reduplication (that was used

in Gt), which bears a sort of vestigial (that was used in Gt) for

(hātan – heht – hehton – hāten) or without it (rædan –

reord – reordon – ræden).

-

советую запомнить ,

кому еще это не въелось от И.П.

-

советую запомнить ,

кому еще это не въелось от И.П.

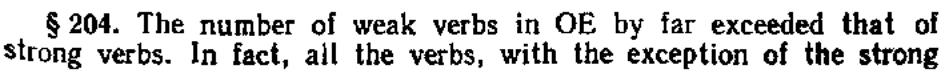

The

one must elaborate the weak class verbs (4 classes). Their forms were

built not with the Ablaut usage, but with the help of suffixation

(the dental suffix –t, -d). In contrast with strong verbs this

class verbs is exclusively Germanic phenomenon, with no analogies in

other IE lang-s. However, one of the theory of dental suffix origin

compares the past participle with it namely with Part. 2 in other

lang-s (amatus, битый).

And the other theory that explains the past form of weak verbs

proposes to connect it with the past form of the verb ‘to do”.

For instance the Gt Past. Pl. hausidedum mirrors in terms of its 2nd

part the German verb of the same form taten. Anyway, one can

confidently affirm that the weak verbs are relatively verbs not so

old verb system (in comparison to strong).

So, one could say that whereas the strong verbs were still widely-used and resented in OE period, the expansion of weak verbs began occurring already in OE period.

To talk about modern modal verbs, one can trace them to the so called preterit-present verbs, those that used both weak and strong verbs means to build their conjugational forms. Their present tense forms are similar in terms of building with past tense form of strong verbs, and preterit-present past tense forms are alike to weak verbs’ past tense forms. In terms of modern modal verbs, one must single out such preterit-present verbs among others:cunnan (can), sculan (should) and magan (may).g

ME

Due to the general changes in the English lang., changes in the verb occurred too. The infinitive form’s and past tense plural form’s ending –an, -on reduced to –en. And past plural forms of IV and V class strong verbs begin to infiltrate the singular forms. Classes began influencing classes. For instance, some verbs of the V class change into the IV one. (sp(r)eken, trenden). In the ME period some strong verbs begin to conjugate alike to weak verbs. The influence of the latter ones rises. One can also mention some verbs of French and Scandinavian origin that appeared in English. Scandinavian taken (from Sc. taka) as well as thriven is conjugated as a VI and I class strong verbs respectively. However the conjugation similar to weak verb’s one prevailed both in French (striven, punishen, catchen, etc) and in Scandinavian borrowings. In ME the Participle I was eventually built only with the ending –inge, that crowded out other endings. The preterit-present verbs changed their changed their forms in accordance with the general changes in the verb system.

NE

New English period is marked with profound changes in the general lag’s system and in the verb’s one. The main forms of strong verbs reduced to three (infinitive, the sole past form and part. 2) I many verbs the past form forced out the past participle form (strike – struck – struck)/ In some cases everything happened vice versa: part. 2 influenced the past form: bite – bit – bit(ten). Very deep changed occurred in the inflectional system. A lot of personal endings disappeared quicker or more gradually: 1st p. sg present, pl form, infinitive, 2p. sg present. –eth 3p. sg present > -s. However archic forms were used for poetic aims. The forms (and even not all of the) stabilized in the XVII-XVIII cent. Actually even the class differentiation of both strong and weak verbs about XVIII lost its sense. In weak verbs –d suffix for past tense eventually became the dominating one.

The most important feature of NE period in terms of verbs s the soaring importance of weak verbs. A lot of verbs changed he class form strong to weak (grip, climb, leap, etc). Some of them preserved theire strong forms alongside with the weak ones (cleave – cleft/clove – cleft/cloven). But the reverse process took place too. The verb hide – hid – hidden became a strong verb of the 1st class.

Anyway the process of change of irregualar/strong verbs into regular/weak is not finished yet. It occurs now.

A lot of preterit-present verbs went out of usage (thurven, mon, etc), but those that not, acquired the modal verb’s features (they didn’t bear any personal endings, even for 3d p. sg present). Those are: can, may/might, should/shall.