- •Foreword

- •Preface the purpose of this book

- •Intended audience

- •Book organization

- •About b2t training

- •Chapter 1: Possess a Clear Understanding of Business Analysis overview

- •What is business analysis?

- •Business Analysis vs. Software Development

- •The Role of the Business Analyst

- •Business Analyst Traits

- •History of Business Analysis

- •Where Do Business Analysts Come From?

- •From it

- •Case in Point

- •From Business

- •Case in Point

- •Where Do Business Analysts Report?

- •Who makes a great business analyst?

- •Case in Point

- •Business Analyst Suitability (- відповідність) Questionnaire

- •Suitability Questionnaire

- •Answers

- •Business Analyst Career Progression

- •Key business analysis terms/concepts

- •What Is a Requirement?

- •Iiba Business Analysis Body of Knowledge® (babok®) definition of requirement:

- •Core Requirements Components

- •Why Document Requirements?

- •Why Do Requirements Need to Be Detailed?

- •High-Level Requirements Are Interpreted Differently

- •Many Analysts Only Use Text to Document Requirements

- •Complex Business Rules Must Be Found

- •Requirements Must Be Translated

- •Case in Point

- •What Is a Project?

- •What Is a Product?

- •What Is a Solution?

- •Case in Point

- •What Is a Deliverable?

- •System vs. Software

- •It Depends

- •Business analysis certification

- •Iiba babok®

- •Summary of key points

- •Bibliography

- •Chapter 2: Know Your Audience overview

- •Establish trust with your stakeholders

- •With whom does the business analyst work?

- •Executive or Project Sponsor

- •Case in Point: Giving the Sponsor Bad News

- •Project Manager

- •Why Does a Project Need a Project Manager and a Business Analyst?

- •Project Manager and Business Analyst Skills Comparison

- •Tips for Those Performing Both Roles

- •Other Business Analysis Professionals

- •Subject Matter Experts and Users

- •Getting to Know Your Subject Matter Experts

- •A Manager Who Does Not Understand His or Her Employees’ Work

- •When the Expert Is Not Really an Expert

- •When the Expert Is Truly an Expert

- •The Expert Who Is Reluctant to Talk

- •The Expert Who Is Angry about Previous Project Failures

- •The Expert Who Hates His or Her Job

- •Quality Assurance Analyst

- •When “qa” Is a Bad Word in Your Organization

- •Usability Professional

- •It Architect

- •Case in Point

- •It Developer

- •Case in Point

- •The Developer Who Is Very Creative

- •The Developer Who Codes Exactly to Specs

- •The Developer’s Industry Knowledge

- •Data Administrator/Architect/Analyst

- •Database Designer/Administrator

- •Stakeholder Analysis

- •Balancing stakeholder needs

- •Case in Point

- •Understanding the Political Environment

- •Working with dispersed teams

- •Physical Distance

- •Time Zone Differences

- •Nationality/Cultural Differences

- •Language Differences

- •Using Team Collaboration Tools

- •Using a Shared Presentation

- •Sharing a Document

- •Summary of key points

- •Bibliography

- •Chapter 3: Know Your Project

- •Why has the organization decided to fund this project?

- •Business Case Development

- •Case in Point

- •Project Initiated Because of a Problem

- •Case in Point

- •Project Initiated to Eliminate Costs (Jobs)

- •Project Initiated by Outside Regulation

- •Project Initiated by an Opportunity

- •Projects for Marketing or Advertising

- •Case in Point

- •Projects to Align Business Processes

- •Strategic planning

- •Portfolio and Program Management

- •How Does Your Project Relate to Others?

- •Enterprise Architecture

- •Business Architecture

- •The Organizational Chart

- •Locations

- •Swot (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats)

- •Products

- •Information Architecture

- •Application Architecture

- •Technology Architecture

- •Case in Point

- •Security Architecture

- •Communicating Strategic Plans

- •Project Identification

- •Project initiation

- •Naming the Project

- •Initiation

- •Approach or Methodology

- •Statement of Purpose

- •Objectives

- •Problems/Opportunities

- •Stakeholders

- •Business Risks

- •Items Out of Scope

- •Assumptions

- •Scope of the Business Area

- •Scoping the Analysis Area Using a Context-Level Data Flow Diagram

- •Area of Study

- •High-Level Business Processes

- •Scoping the Analysis Area Using a Use Case Diagram

- •Project Initiation Summary Revisit Scope Frequently

- •Scope Creep

- •Summary of key points

- •Bibliography

- •Chapter 4: Know Your Business Environment overview

- •Case in Point

- •How does a business analyst learn about the enterprise?

- •Read the Company’s Marketing Materials

- •Read the Company’s Financial Reports

- •Review the Corporate Strategic Plan

- •Seeing things from the business perspective

- •Case in Point

- •Prioritizing Requests

- •Case in Point

- •How a business analyst learns the business: elicitation techniques

- •Review Existing Documentation

- •Case in Point

- •Observation

- •Case in Point

- •Case in Point

- •Interviews

- •Surveys and Questionnaires

- •Facilitated Sessions

- •Why Use a Facilitated Session?

- •Challenges for the Business Analyst as the Facilitator

- •Focus Groups

- •Competitive Analysis

- •Interface Analysis

- •Learn the current (as is) system

- •Case in Point

- •What is a business process?

- •Essential Analysis

- •Perfect Technology

- •No Storage Limitations or Constraints

- •Case in Point

- •Completely Error-Free Processing

- •Case in Point

- •No Performance Limitations

- •Technology Is Available at No Cost

- •Case in Point

- •Summary of Perfect Technology

- •Essential Business Processes

- •Case in Point

- •What Is the Difference between a Process and a Use Case?

- •Describing a Process

- •Seeing Things from the Top and from the Bottom

- •Implementation Planning

- •Training

- •Rollout Plan

- •Schedule

- •Metrics

- •Procedures/Organizational Changes

- •Summary of tips for learning your business

- •Summary of key points

- •Bibliography

- •Chapter 5: Know Your Technical Environment overview

- •Case in Point

- •Why does a business analyst need to understand the technical environment?

- •Understand Technology, But Don’t Talk Like a Technologist

- •Case in Point

- •What does a business analyst need to know about technology?

- •Software Development/Programming Terminology

- •Does a Business Analyst Need to Know How to Develop Software?

- •Software Development Methodologies

- •Methodology/Software Development Life Cycle

- •Waterfall

- •Planning Phase

- •Analysis Phase

- •Design Phase

- •Construction Phase

- •Testing Phase

- •Information Engineering

- •Joint Application Development/Design

- •Rapid Application Development

- •Iterative/Incremental Development Approaches

- •Object-Oriented Analysis and Design

- •Rational Unified Process

- •Agile Development Approaches

- •An Organization’s Formal Methodology

- •Why Don’t Most Methodologies Detail the Business Analysis Approach?

- •An Organization’s Informal Standards

- •Technical Architecture

- •Operating Systems

- •Case in Point

- •Computer Networking

- •Data Management

- •Relational Database

- •Structured Query Language

- •Software Usability/Human Interface Design

- •Software Testing

- •Case in Point

- •Software Testing Phases

- •Unit Testing

- •Integration Testing

- •System Testing

- •Regression Testing

- •Case in Point

- •User Acceptance Testing

- •Post-Implementation User Assessment

- •Working with it Communicating with Developers

- •When to Get it Involved in a Project

- •It Corporate Culture

- •Summary of key points

- •Bibliography

- •Chapter 6: Know Your Analysis Techniques overview

- •Case in Point

- •Categorizing and presenting requirements Collecting and Managing Requirements

- •What Is a Requirement?

- •Categorizing Requirements

- •Case in Point

- •Why Categorize Requirements?

- •Developing a System for Organizing Requirements

- •Iiba babok Categories

- •A Recommended Categorization System

- •Business Requirements

- •Functional Requirements

- •Technical Requirements

- •Core requirements components

- •Overview of Core Requirements Components Data (Entities and Attributes)

- •Processes (Use Cases)

- •External Agents (Actors)

- •Business Rules

- •Case in Point

- •Core Requirements Component: Entities (Data)

- •Core Requirements Component: Attributes (Data)

- •Attribute Uniqueness

- •Mandatory or Optional

- •Attribute Repetitions

- •Core Requirements Component: Processes (Use Cases)

- •Core Requirements Component: External Agents (Actors)

- •Internal vs. External

- •Core Requirements Component: Business Rules

- •Finding Business Rules

- •Analysis techniques and presentation formats

- •Glossary

- •Workflow Diagrams

- •Why Use Workflow Diagrams?

- •Entity Relationship Diagramming

- •Why Build a Logical Data Model?

- •Business Process Modeling with the Decomposition Diagram

- •Why Build a Decomposition Diagram?

- •Use Case Diagram

- •Use Case Descriptions

- •Why Use Use Cases?

- •Case in Point

- •Prototypes/Simulations

- •Why Use Prototypes/Simulations?

- •Other Techniques Event Modeling

- •Entity State Transition/uml State Machine Diagrams

- •Object Modeling/Class Modeling

- •User Stories

- •Traceability Matrices

- •Gap Analysis

- •Data Flow Diagramming

- •Choosing the Appropriate Techniques

- •Using Text to Present Requirements

- •Using Graphics to Present Requirements

- •Using a Combination of Text and Graphics

- •Choosing an Approach

- •Case in Point

- •Business Analyst Preferences

- •Case in Point

- •Subject Matter Expert Preferences

- •Case in Point

- •Developer Preferences

- •Project Manager Preferences

- •Standards

- •Case in Point

- •As is vs. To be analysis

- •Packaging requirements How Formally Should Requirements Be Documented?

- •What Is a Requirements Package?

- •Case in Point

- •Request for Proposal Requirements Package

- •Characteristics of Excellent Requirements

- •Getting Sign-Off

- •Requirements Tools, Repositories, and Management

- •Summary of key points

- •Bibliography

- •Chapter 7: Increase Your Value overview

- •Build your foundation Skill: Get Started

- •Skill: Think Analytically

- •Skill: Note Taking

- •Technique: Brainstorming

- •Skill: Work with Complex Details

- •Case in Point

- •How Much Detail? Just Enough!

- •Case in Point

- •Time management Skill: Understand the Nature of Project Work

- •Skill: Work on the Most Important Work First (Prioritize)

- •Case in Point

- •Technique: Understand the 80-20 Rule

- •Technique: Timeboxing

- •Build your relationships and communication skills Skill: Build Strong Relationships

- •Skill: Ask the Right Questions

- •Case in Point

- •Skill: Listen Actively

- •Barriers to Listening

- •Listening for Requirements

- •Skill: Write Effectively

- •Case in Point

- •Skill: Make Excellent Presentations

- •Skill: Facilitate and Build Consensus

- •Skill: Conduct Effective Meetings

- •Prepare for the Meeting/Select Appropriate Attendees

- •Meeting Agenda

- •Conducting the Meeting

- •Tips for Conducting Successful Meetings

- •Follow-Up/Meeting Minutes

- •Skill: Conduct Requirements Reviews

- •How to Conduct a Review

- •Step 1. Decide on the Purpose of the Review

- •Step 2. Schedule Time with Participants

- •Steps 3 and 4. Distribute Review Materials and Have Participants Review Materials Prior to the Session

- •Case in Point

- •Step 5. Conduct the Review Session

- •Steps 6 and 7. Record Review Notes and Update Material

- •Step 8. Conduct a Second Review If Necessary

- •Typical Requirements Feedback Corrections

- •Missing Requirements

- •Unclear Sentences

- •Scope Creep

- •Keep learning new analysis techniques Technique: Avoid Analysis Paralysis!

- •Technique: Root Cause Analysis

- •The Five Whys

- •Case in Point

- •Skill: Intelligent Disobedience

- •Continually improve your skills

- •Skill: Make Recommendations for Solutions

- •Understand the Problem

- •Imagine Possible Solutions

- •Case in Point

- •Evaluate Solutions to Select the Best

- •Skill: Be Able to Accept Constructive Criticism

- •Case in Point

- •Skill: Recognize and Act on Your Weaknesses

- •Technique: Lessons Learned

- •Business analysis planning

- •Technique: Map the Project

- •Examples of Mapped Projects

- •Skill: Plan Your Work

- •Technique: Assess Business Impact

- •Case in Point

- •Factors That Determine Business Impact

- •Case in Point

- •Technique: Conduct Stakeholder Analysis

- •Technique: Plan Your Communications

- •Skill: Choose Appropriate Requirements Deliverables

- •Skill: Develop a Business Analysis Task List

- •Skill: Estimate Your Time

- •Summary of key points

- •Bibliography

Case in Point

I recently met a man who is a business process analyst. I spoke with him about a new job opportunity that he was considering. He said that he didn’t know what software application the company uses, but that it doesn’t matter. He has specialized in the distribution business and enjoys coming into new organizations, observing their current procedures, and making recommendations. He said to me: “You get an order, you pack it, and you ship it. How difficult can it be?” He had just named the essential processes in his business area. This was not meant to minimize the complexity of the distribution process. After working at many different companies, selling many different products, using different inventory and shipping software systems, he recognized that the core business processes are the same.

|

|

Table 4.2: Differences Between a Process and a Use Case |

|

Process |

Use Case |

Business activity |

Goal of the system needed by a particular actor |

Named with a verb describing the work performed by the business (validate order) |

Named with a verb describing the action taken by the actor (place order) |

Defined without reference to who performs it |

Tied to a specific role (the actor) |

Defined so that it could be performed by any business worker and/or an external customer/ supplier/vendor |

Designed to be executed by the actor (often specified as a conversation between the actor and the software) |

Always defined as independent of specific procedures or technologies |

Business use cases may be independent of tech-nology; system use cases describe how the soft-ware will support the activity |

What Is the Difference between a Process and a Use Case?

Use cases have become very popular and are used by some project teams instead of processes or even in lieu of any other requirements components (see Chapter 6). Be sure to understand how your organization uses these requirements components. Because processes are defined independent of the who and how, they are more easily reused and allow for more design flexibility. Table 4.2 lists the differences between processes and use cases. Both should be defined independent of any current organizational structure or title.

Describing a Process

As each business process is identified and named, detailed questions should be answered about why it is done, what information it uses, and what business rules constrain or guide it. The successful analyst will delve deeply into each essential business process to make sure that its purpose and fundamental value to the organization are captured. Many of these questions may be difficult for subject matter experts to answer. The analyst must work with the business stakeholders to talk through the whys and whats of the process because only a deep, thorough understanding will give rise to improvements. By discussing each process in detail, the business subject matter expert thinks about the work in a new way. Often during analysis work, the subject matter expert comes up with a process improvement idea. This occurs because the process is being examined from a different perspective. Figure 4.1 is a template for describing a business process.

Naming processes is important yet is often done carelessly. Names should be chosen to accurately communicate the activity of the business (verb-noun), so that when the process is shown on diagrams, it is immediately recognizable. Process names should describe the what, not the how. Analysts can use the assumptions of perfect technology and the business glossary to help determine good business names.

Strong verbs to use in process names include:

Accept

Add

Calculate

Capture

Communicate

Delete

Dispatch

Generate

Place

Prepare

Provide

Receive

Record

Remit

Request

Send

Submit

Tabulate

Update

Validate

Verify

Figure

4.1: Business

Process Template

Figure

4.1: Business

Process Template

In addition to a strong, clear name, a description of the process must also be written. A name can only convey the basic information about what type of activity (the verb) is being performed on what type of data (the noun). A few sentences will elaborate on this name, providing all stakeholders with a clear, consistent understanding of the process. This description should explain why the process is important.

Analyzing a process includes understanding which, if any, external agents (organizations, people, and systems) interact with it. Most processes are performed in a business because an external agent has requested something. Understanding which externals are involved with each process provides additional information about why a process is performed.

During process analysis, it is important for the analyst to ask questions about sequence. What happens before this process (i.e., what triggers it)? What other processes are triggered by the completion of this one? And most importantly, why are processes performed in this order? One of the common mistakes made by new analysts is assuming that the current order of work is a requirement and must be maintained. This assumption locks the business into its current procedures and leaves little room for creative new solutions.

Each process must be examined for business rules. There will not always be a rule for every process, but most processes are guided by some type of a constraint (e.g., invoices are paid on the 15th and the last day of each month). As you are identifying business rules that are used during a process, think about whether each rule may also be used by another process. These shared rules should be defined consistently and their descriptions reused to save analysis time. Business rules will be discussed further in Chapter 6.

For each process, the analyst should think about the individual data elements needed to successfully perform it. These data elements may (1) come into the process from an outside source, (2) be created by the process, or (3) be retrieved from a storage facility (filing cabinet, database) inside the business. Businesses store a lot of data so that processes can use them whenever needed (e.g., customer addresses are stored in a database so that customers are not asked for their address every time they place an order). Process analysis includes verification that all of the data elements needed by a process are available to it. The importance of data requirements will also be discussed in Chapter 6.

While analyzing, naming, and documenting essential business processes are important work of the BA, understanding how a process is currently performed can sometimes be just as important. Often, when you are asking stakeholders questions about the core business activity and working to understand it independent of current technology limitations, they want to talk about the how. They feel that it is important for you to know, step by step, how they perform this business process. Listen carefully and make the notes that you need. Listen for gaps in the process or between processes. If you know that the technology currently supporting the process will be changing, understanding details about the current how may not be critical. Listen for problems and complaints to make sure that the new design will address the issues.

In addition, make notes about metrics. How long does the process take? How many times is it performed? Make sure you also understand who currently performs the process and who benefits from it. All of these things may change as your team brainstorms about alternative solutions. Understanding how the work is currently done prevents you from redesigning the same system. Finally, when talking with stakeholders about a process, listen to their suggestions for changes. They may have some great ideas about how the process could be made more efficient.

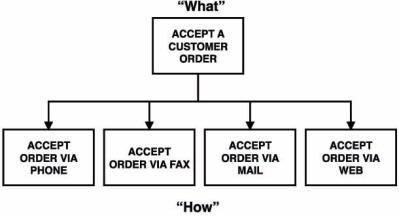

When the reason for a process is understood, as well as its constraints and data components, different creative approaches to accomplishing it can be imagined. In what ways could the business receive an order ? Via a text message? In an e-mail message? On a handwritten note? Suppose the products being sold are car parts. Could the car itself send an electronic message when one of its parts is wearing out and place an order for a new one? Figure 4.2 shows an example of an essential process: accept a customer order. This core business activity may be performed successfully in many different ways (different hows). When business requirements and processes are documented independent of current technology, they can be reused on future projects in the same business area. This can save the BA a significant amount of time.

Figure

4.2: Business

Process: Accept Customer Order

Figure

4.2: Business

Process: Accept Customer Order

This is where an analyst’s creativity can really shine. True innovation occurs when the innovator strips away the current procedures and looks at the base requirements. Then he or she can be creative in meeting those requirements. When you see a new product or service offered, think about how the inventor might have come up with the idea. Was it in response to a problem? Was it designed with the goal of increasing productivity or quality? Was it created to increase sales? Remember the primary business drivers (i.e., increase revenue, decrease costs). Any improvements made to an individual process roll up to help the entire organization.

In consumer product development, a brainstorming technique is used for package design. Think of an everyday common consumer product like soup. Now think of different types of packaging used for other items and imagine selling soup in that packaging. Soup in a box? Soup in a tube? Soup in a cylinder? Soup in a plastic jug? This technique illustrates the importance of finding the core business component and imagining it being presented in different ways. Once an essential process is understood, the analyst, business stakeholders, and solution team can imagine different procedures and systems that would support it.

Excellent BAs balance creativity with facts or metrics. Each process should be measured for its resource use, time to complete, efficiency, and number of times performed.

Process improvements are evaluated by their improved metrics. Can the improved system get the process done faster? How much faster? Can the improved process allow the organization to handle larger volumes of transactions? How many? Will the improved process result in higher quality products or services? By how much? Excellent business analysis professionals ask these questions because they understand that measuring process improvement quantifies the success of a project.

Six Sigma® is an approach to business process improvement that relies heavily on metrics. Sigma is a Greek letter assigned to represent the amount of variation or inconsistency exhibited by a measurable outcome. The name Six Sigma refers to the mathematical boundary within which errors are allowed. A Six Sigma capable process has a targeted quality performance goal of no more than 3.4 defects per million opportunities. The objective is to eliminate defects and variations in processes. When processes and their results are consistently measured, an organization can monitor improvements in efficiency and quality. It can also recognize decreases in productivity and respond more quickly. More and more organizations are using metrics to monitor performance. They are also building and buying complex business process monitoring systems and assigning process owners inside business units to monitor process effectiveness. To learn more about Six Sigma, read The Six Sigma Way: How GE, Motorola, and Other Top Companies Are Honing Their Performance (Pande et al., 2000).

When an essential business process is analyzed and described, this business requirement can be reused again and again. A business requirement is reusable when it is described independent of current procedures and technology. To help describe processes without embedding current technology, use the concept of perfect technology.