- •Sociolinguistics Class: Lectures, Questions, Handouts and Articles Written and compiled by Todd m. Ferry Starobilsk Department of Lugansk National Pedagogical University

- •Introduction to the topic:

- •Sociolinguistics: syllabus

- •Introduction:

- •Use at least three sources.

- •Footnote all citations.

- •Language and culture

- •Doctrine of linguistic relavtivity

- •Chomsky

- •Sapir_whorf hypothesis

- •The point

- •In summation

- •Sociolinguistics—again

- •Language definition part II.

- •What is a variety? slide#2

- •Slide #3

- •Slide #4 and #5

- •Slide #6

- •Slide #7

- •**Please look at your hand out

- •Regional dialects

- •Isoglosses

- •Variables

- •Bet and better, sometimes pronounced without the “t” like be-h and be-hher

- •He don’t mean no harm to nobody

- •Idiolect: redirect to slide # 5

- •Problems with accent

- •Lecture 3: When Languages Collide

- •Review: code/language

- •Slide 1: code switching

- •Review: speech community

- •Code-mixing

- •Slide 4: surzhyk

- •Borrowing

- •Languages collide

- •Pidgins

- •Slide 5: pidgin

- •Slide 5.5 and slide 6

- •Slide 10: Hawaiian Pidgin-Creole

- •Hawiian Pidgin-Creole

- •Slide 11: hawaiian pidgin-creole history History

- •Slide 13: hawiian pidgin-creole grammar/pro. Pronunciation

- •Grammatical Features

- •Slide: 14 gullah language

- •African origins

- •Lorenzo Turner's research

- •Slide 15: gullah verbal system Gullah verbs

- •Gullah language today

- •Slide 18: language shift language shift

- •Language planning and policy

- •Implicit language policy

- •Language planning in ukraine

- •Ukrainian language (1917-1932) Ukrainianization and tolerance

- •Russian language (1932-1953)

- •Russian language 1970’s-1980’s

- •Independence to the present

- •Slide 23: census data

- •Social interaction

- •Speech acts

- •Or for example ordering food at a restaurant

- •Now, taking it a step farther, what if your speech act fails? What if you do not say, “It is getting cold in here,” so that your friend understands your meaning?

- •Speech as skilled work

- •Norms governing speech

- •1. Norms governing what can be talked about: taboos and euphemism.

- •2. Norms governing non-verbal communication: body language

- •What does eye contact mean?

- •Conversational structure

- •Turn-taking

- •4. Norms governing the number of people who talk at once:

- •5. Norms governing the number of interruptions

- •We can say it more clearly as: I respect your right to…

- •Solidarity and power

- •Greetings and farewells

- •Labov, linguistic variable, middle class

- •English poll

- •Pronunciation and class dropping the g

- •Norwich, england

- •Los angeles

- •Dropping the h

- •Dropping the r or r-lessness—intrusive r—rhoticity

- •Labov’s new york department store

- •British english r-Lessness

- •Other r-variations

- •Various social dialects

- •In britain cockney—london, england (class based social dialect)

- •Characteristics

- •Aspect marking

- •New York English and Southern American English

- •You and me and discrimination

- •Aave in Education

- •Gender discrimination

- •History

- •Affirmative positions

- •Neutral positions

- •Negative positions

- •Articles

- •Sociolinguistics

- •Walt Wolfram

- •Language as Social Behavior

- •Suggested Readings

- •Which comes first, language or thought? Babies think first

- •Americans are Ruining English

- •American English is ‘very corrupting’

- •One way Americans are ruining English is by changing it

- •A language - or anything else that does not change - is dead

- •Both American and British have changed and go on changing

- •Sociolinguistics Basics

- •What is dialect?

- •Vocabulary sometimes varies by region

- •People adjust the way they talk to their social situation

- •State of American

- •Is English falling apart?

- •Sapir–Whorf hypothesis From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- •[Edit] History

- •[Edit] Experimental support

- •[Edit] Criticism

- •[Edit] Linguistic determinism

- •[Edit] Fictional presence

- •[Edit] Quotations

- •[Edit] People

- •[Edit] Further reading

- •[Edit] External links Speech act From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- •[Edit] Examples

- •[Edit] History

- •[Edit] Indirect speech acts

- •[Edit] Illocutionary acts

- •[Edit] John Searle's theory of "indirect speech acts"

- •[Edit] In language development

- •[Edit] In computer science

- •Performative utterance From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- •[Edit] Austin's definition

- •[Edit] Distinguishing performatives from other utterances

- •[Edit] Are performatives truth-evaluable?

- •[Edit] Sedgwick's account of performatives

- •[Edit] Naming

- •[Edit] Descriptives and promises

- •[Edit] Examples

- •[Edit] Performative writing

- •[Edit] Sources

- •Intas Project: Language policy in Ukraine

- •Resolution On The Oakland "Ebonics" Issue Unanimously Adopted at the Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America Chicago, Illinois January 3, l997

- •Selected references (books only)

- •From “Ukrainian language” in Wikipedia Ukrainianization and tolerance

- •[Edit] Persecution and russification

- •[Edit] The Khrushchev thaw

- •[Edit] The Shelest period

- •[Edit] The Shcherbytsky period

- •[Edit] Gorbachev and perestroika

- •[Edit] Independence in the modern era

- •Dialects of Ukrainian

- •[Edit] Ukrainophone population

- •Questions from articles for seminars

- •Sociolinguistics Discussion Questions for Seminar Two:

- •Sociolinguistics Discussion Questions for Seminar Three:

- •Handouts Lecture 1. Definitions, Chomsky and Sapir-Whorf

- •Social interaction

- •The norms governing speech

- •We can say it more clearly as: I respect your right to…

- •Aave aspectual system

- •Additional materials Dialect Map of American English

- •Southeastern dialects:

[Edit] The Shelest period

The Communist Party leader Petro Shelest pursued a policy of defending Ukraine's interests within the Soviet Union. He proudly promoted the beauty of the Ukrainian language and developed plans to expand the role of Ukrainian in higher education. He was removed, however, after only a brief reign, for being too lenient on Ukrainian nationalism.

[Edit] The Shcherbytsky period

The new party boss, Shcherbytsky, purged the local party, was fierce in suppressing dissent, and used the Russian language at official functions even at local levels. His policy of Russification was lessened only slightly after 1985.

[Edit] Gorbachev and perestroika

The management of dissent by the local Ukrainian Communist Party was more fierce and thorough than in other parts of the Soviet Union. As a result, at the start of the Gorbachev reforms, Ukraine under Shcherbytsky was slower to liberalize than Russia itself.

Although Ukrainian still remained the native language for the majority in the nation on the eve of Ukrainian independence, a significant share of ethnic Ukrainians were Russified. The Russian language was the dominant vehicle, not just of government function, but of the media, commerce, and modernity itself. This was substantially less the case for western Ukraine, which escaped the artificial famine, Great Purge, and most of Stalinism. And this region became the piedmont of a hearty, if only partial renaissance of the Ukrainian language during independence

[Edit] Independence in the modern era

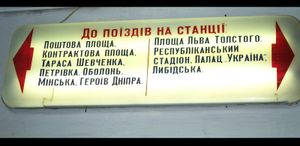

Modern signs in the Kiev Metro are in Ukrainian. The evolution in their language followed the changes in the language policies in post-war Ukraine. Originally, all signs and voice announcements in the metro were in Ukrainian, but their language was changed to Russian in the early 1980s, at the height of Shcherbytsky's gradual Russification. In the perestroika liberalization of the late 1980s, the signs were changed to bilingual. This was accompanied by bilingual voice announcements in the trains. In the early 1990s, both signs and voice announcements were changed again from bilingual to Ukrainian-only during the Ukrainianization campaign that followed Ukraine's independence.

Since 1991, independent Ukraine has made Ukrainian the only official state language and implemented government policies to broaden the use of Ukrainian. The educational system in Ukraine has been transformed over the first decade of independence from a system that is partly Ukrainian to one that is overwhelmingly so. The government has also mandated a progressively increased role for Ukrainian in the media and commerce. In some cases, the abrupt changing of the language of instruction in institutions of secondary and higher education, led to the charges of Ukrainianization, raised mostly by the Russian-speaking population. However, the transition lacked most of the controversies that surrounded the de-russification in several of the other former Soviet Republics.

With time, most residents, including ethnic Russians, people of mixed origin, and Russian-speaking Ukrainians started to self-identify as Ukrainian nationals, even though remaining largely Russophone. The state became truly bilingual as most of its population had already been. The Russian language still dominates the print media in most of Ukraine and private radio and TV broadcasting in the eastern, southern, and to a lesser degree central regions. The state-controlled broadcast media became exclusively Ukrainian but that had little influence on the audience because of their programs' low ratings. There are few obstacles to the usage of Russian in commerce and it is de facto still occasionally used in the government affairs.

In the 2001 census, 67.5% of the country population named Ukrainian as their native language (a 2.8% increase from 1989), while 29.6% named Russian (a 3.2% decrease). It should be noted, though, that for many Ukrainians (of various ethnic descent), the term native language may not necessarily associate with the language they use more frequently. The overwhelming majority of ethnic Ukrainians consider the Ukrainian language native, including those who often speak Russian and Surzhyk (a blend of Russian vocabulary with Ukrainian grammar and pronunciation). For example, according to the official 2001 census data [5] approximately 75% of Kiev's population responded "Ukrainian" to the native language (ridna mova) census question, and roughly 25% responded "Russian". On the other hand, when the question "What language do you use in everyday life?" was asked in the sociological survey, the Kievans' answers were distributed as follows [6]: "mostly Russian": 52%, "both Russian and Ukrainian in equal measure": 32%, "mostly Ukrainian": 14%, "exclusively Ukrainian": 4.3%. Ethnic minorities, such as Romanians, Tatars and Jews usually use Russian as their lingua franca. But there are tendencies within minority groups to prefer Ukrainian in many situations. The Jewish writer Aleksandr Abramovic Bejderman from the mainly Russian speaking city of Odessa is now writing most of his dramas in Ukrainian language. Emotional relationship towards Ukrainian is partly changing in Southern and Eastern areas, too.