- •Overcoming social anxiety and shyness

- •Gillian butler

- •Important Note

- •Isbn 978-1-85487-703-1

- •Introduction

- •Part one Understanding Social Anxiety

- •Varieties of social anxiety

- •Is shyness a form of social anxiety, or is it something different?

- •Implications

- •Is social anxiety all in the mind? The central role of thinking in social anxiety

- •Images in social anxiety

- •Figure 4.1 Summarizing the causes of social anxiety

- •Figure 5.1 The Clark and Wells model of social anxiety

- •Illustrating the main processes that keep social anxiety going

- •Figure 5.2 Practical example of the model

- •Part two Overcoming Social Anxiety

- •What is the worst thing that could happen to you?

- •Is self-confidence different from this?

- •Part three Some Optional Extras

- •Identify your internal critical voice

- •Identify your triggers

- •Institute for Behavior Therapy

Figure 4.1 Summarizing the causes of social anxiety

Vulnerability factors are long-standing characteristics that make someone susceptible to bouts of social anxiety, and they are both biological and psychological. Psychological vulnerability factors can be summarized as the messages that have been gleaned from the things that happened earlier in life – from experience. Stresses include the demands of a person’s particular stage of life and any specific stressful factors or circumstances that are affecting them at the present time. These may be internal pressures, such as the desire to succeed, the need to be liked, or the fear of being alone, as well as external ones, so what counts as a stress varies from person to person.

The diagram shows that for people with social anxiety, the problem will occur when they encounter situations that provoke the fear of doing something that will be humiliating or embarrassing. Once they feel anxious then a vicious cycle comes into play, and perpetuates the problem. Reactions to anxiety, such as looking for a way out, worrying about what others might notice, feeling self-conscious or finding it difficult to speak fluently, feed back to make the anxiety worse. So whatever caused the anxiety in the first place may be different from the reactions that keep it going. The cycle that perpetuates the anxiety is one of the most important factors to be considered when it comes to overcoming anxiety. Breaking the cycle allows the anxiety to subside, and then it is easier to see how to deal with the stresses and personal vulnerabilities that may otherwise bring it back again.

Some concluding comments

People depend on each other; they always have. In primitive times, for example, being excluded from the group could have threatened a person’s chances of survival. So the need to make oneself acceptable is likely to be deeply ingrained – and the ability to do so could even increase the chances of successfully reproducing and raising a new generation of children. People need a social life, for protection and for division of labour as well as for procreation. Being alone and isolated, without companions, is threatening, and hard to tolerate for long. It makes us feel vulnerable, so it is no wonder that isolation is used as a form of punishment, or that hostility and rejection are alarming experiences to deal with. It takes a huge amount of discipline and self-denial to live as a hermit, partly because having social support available provides a degree of protection. When bad things happen, those people who have support from others around them fare better than those who do not – which is not to say that social life does not have its own difficulties and dangers too.

These difficulties and dangers were all too apparent to Jim, whose inability to answer the question he was asked introduced this chapter (see here). He became tongue-tied and anxious when asked how the new arrangements for taking holidays from work were going to affect him. If other people were not the cause of the problem for Jim, then what was? We know nothing about the vulnerability factors in Jim’s case, nor about any stresses, demands or pressures on him that there may have been. All that we know is the reflection of these things in his mind (or the ‘surface’ problem), and this is a common state of affairs. The surface problem dominates Jim’s experience, leaving him as well as us asking the question ‘Why?’ First his mind went blank, as he could not think of anything to say. Then he thought that everyone was looking at him, and became aware of the interminable silence that followed. After speaking he was so preoccupied with his feelings – mortified, embarrassed, angry – that he could no longer follow the conversation, and he ended up berating himself, certain in his mind that he had, yet again, made a bad impression, and that everyone there thought of him as inadequate. The way Jim’s mind works when he is anxious provides the clues for understanding what to do about the problem, and it is immediately clear that we do not have to know everything about all the factors that could have caused it in this case in order to think about how to reduce his anxiety. Jim’s thoughts are central, and they reflect the many processes that are set in motion when someone else’s actions trigger his symptoms of anxiety.

KEY POINTS

Other people are not the main cause of social anxiety. Many other factors contribute to it.

These include both biological factors and environmental ones.

Experience of relationships as we grow up provides the framework for our thinking about how we relate to others, and bad experiences can leave long-lasting impressions.

Social life presents different demands at different stages.

Vulnerability factors and stresses combine to make someone susceptible to social anxiety, and a vicious cycle operates to keep the anxiety going.

It is not necessary to know everything about what caused the problem in order to work out what to do to alleviate it.

5

Explaining social anxiety: Understanding what happens when someone is socially anxious

In 1995 two clinical psychologists who are researchers as well as clinicians, David Clark and Adrian Wells, published a new model of social anxiety. This model helps us to understand what happens when someone suffering from social anxiety encounters one of the situations that makes them feel anxious. It explains the vicious cycles that keep the problem going and it also suggests how social anxiety can be treated. Many of the suggestions about how to solve the problem in Part Two of this book are based on this model.

Of course, other people before Clark and Wells have had many ideas about how to understand social anxiety, and not everyone working in the field will explain the problem in exactly the same way, even now. However, this new model has many advantages: it is being backed up by careful research that so far has corroborated the ideas behind it; it is consistent with some of the earlier models but more specific than them, and therefore explains more clearly what should be done to overcome the problem; and it recognizes the central part played by thinking, or cognition, in social anxiety. The model can, and no doubt will, be modified as more research is done and more information becomes available.

These are important points, because it is a mistake to assume in any scientific field that theories are fixed. This means that there is no one who has the one and only right and complete answer. The model will stand or fall according to how useful it is – and this one is proving to be exceptionally useful. The assumption behind it is that social anxiety can be understood and explained. It is not a mysterious entity that will always be confusing and puzzling, and the way in which we understand it plays an essential part in understanding what to do about it. Another assumption is that models like this one, that are based on research by experienced clinicians and have been developed out of earlier models and theories, are highly likely to have got much of the story right. There will be enough truth in them for everyone who suffers from the problem to gain something from learning about them. If this particular model does not fit, or fits only partially, then it may be less useful than it otherwise would be, and it may be better to explore other ways of understanding the problem as well, and to search for other suggestions for overcoming it. But there is also highly likely to be a great deal to be gained from thinking about the ways in which this way of understanding the problem makes sense of particular difficulties, as it is a highly versatile model and provides a good way of making sense in most cases.

The current cognitive model of social anxiety

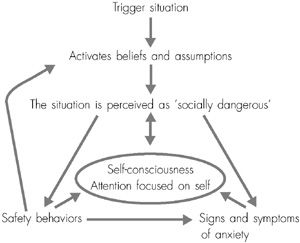

A diagram of the model is provided in Figure 5.1, and the diagram is explained here first before detailed examples are given of how it works out in practice. Although it is rather complicated, it is worth looking at the diagram and seeing how the different parts of it link together to keep social anxiety going.

We already know that the type of situation that triggers a bout of social anxiety varies from person to person. Starting at the top, the diagram shows that when one of these situations occurs it activates particular beliefs and assumptions, for example that other people are being critical or making negative social judgments. As a consequence, the situation is perceived as threatening and interpreted as socially dangerous, giving rise to thoughts such as ‘I’m going to do something wrong here’, ‘I can’t come over well, in the way that other people can’ – thoughts that provoke distress and anxiety. These patterns of thinking are, therefore, at the hub of the whole process.

When this happens, socially anxious people focus in on themselves. They become increasingly self-aware or self-conscious (the central circle in the diagram). As they shift their attention inwards, onto the signs of social anxiety and social ineptitude of which they are painfully aware, and which they think that other people notice, this makes them increasingly conscious of themselves and of the way in which they think they are coming over to others. In technical terms this is described as processing themselves as social objects, almost as if they were able to see themselves from the outside, as an observer would.