- •Introduction: Feminist Therapy—Not for Women Only

- •Women and Madness: Exposing Patriarchy in the Consulting Room

- •Kinder, Kuche, Kirche as Scientific Law: Misogyny in the Science of Psychology

- •Sex Role Stereotyping and Clinical Judgments of Mental Health: Science Supporting Politics

- •Difference Feminism and Feminist Therapy

- •Difference/Equal Value Feminism and Feminist Therapy

- •Multicultural, Global, and Postmodern Feminisms and Feminist Therapy

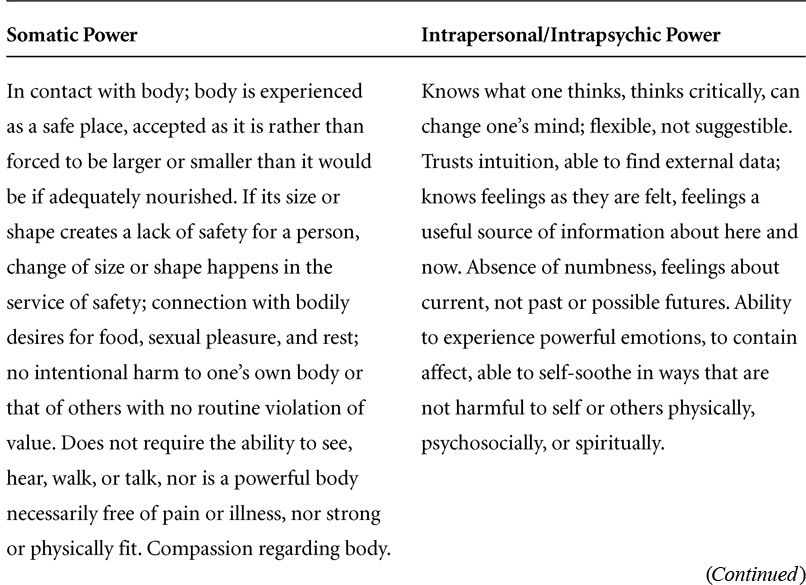

- •Power in the Intrapersonal/intrapsychic Realm

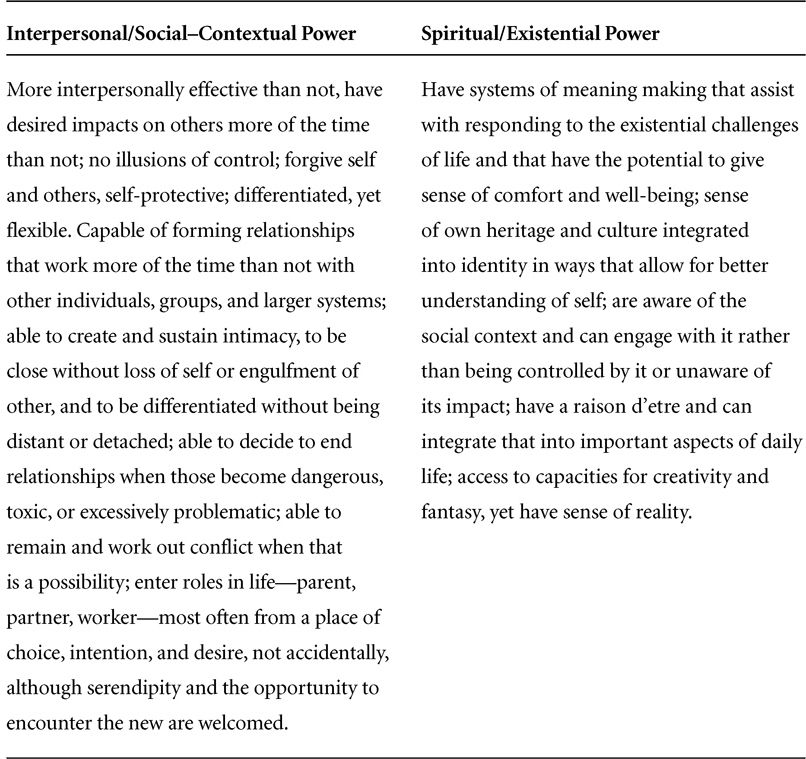

- •Interpersonal/Social–Contextual Power

- •Power in the Spiritual Realm

- •The Egalitarian Relationship

- •Power Dynamics in Therapy: Symbolic Relationship

- •Diagnosis?

- •Bem’s Gender Schema Model

- •Chodorow and the Reproduction of Gender

- •Kaschak’s Self-In-Context

- •Root’s Ecological Model of Identity Development

- •Gender as an Artifact of Power

- •The Question of Formal Assessment in Feminist Practice

- •Micro-Aggression and Insidious Trauma

- •Interpersonal Betrayal as Disempowerment

- •Hays’s addressing Model

- •Root’s Model of Multiple Identities

- •Integrating the Somatic, Intrapsychic, Social, Contextual, and Meaning-Making Dimensions: The Case of Heidi

- •Effectiveness of a Feminist Empowerment Model

- •Feminist Therapy’s Integration With Other Models

- •With Whom Do Feminist Therapists Work?

- •Difficult Contexts

- •Difficult Client Characteristics

- •Feminist Practice in the Absence of the Capacity for Empathy

Multicultural, Global, and Postmodern Feminisms and Feminist Therapy

Today, feminist therapy’s growing edges continue to reflect transformations in the larger feminist political sphere. As feminists from the formerly colonized nations of the Global South begin to have impact on the practice and theory of U.S. and other North American feminist therapists working in collaboration with their colleagues from those parts of the world (Enns, 2004; Kaschak, 2007; Khuankaew & Norsworthy, 2005; Norsworthy, 2007), feminist therapy is also transforming to become more multicultural and global in its analyses. The concept of psychological colonization as a means of understanding the effects of patriarchies on experience has deepened feminist therapists’ comprehension of how and why some patterns of problematic behaviors, thoughts, and feelings may persist in clients, especially those whose experiences resemble that of a colonized nation. The importance of including the spiritual dimension as a component of understanding human experience, asserted initially by feminists of color self-described as womanists (Comas-Díaz, 2008), has begun to gain wide acceptance and visibility in the work of feminist therapy theorists (Brown, 2007). The notion of a man as feminist therapist has become more fully accepted (Brown, 2005; Levant & Silverstein, 2005), and men are seeking training in feminist therapy. Many of the problems addressed by feminist therapists remain familiar from previous eras, such as violence against nondominant group people, discrimination in the form of aversive bias, and denigration of women in the larger social sphere. However, the specific intervention strategies utilized by feminist therapists have continued to transform, partially in response to new information about ways of supporting healing and partly as the understanding of how patriarchy manifests itself become more sophisticated.

Because feminist therapy is primarily theory driven and technically integrative, the next chapter, which addresses theory, constitutes the major focus of this volume. A therapist practices feminist therapy because of her or his epistemology of therapy, not because of what specific behaviors that theoretical model elicits with a given individual sitting across the room. Consequently, everything done by a feminist therapist should reflect and embody that theory and epistemology of power and empowerment within the larger social and political milieu. How those goals are expressed will, however, vary from therapist to therapist, client to client, and even within the course of work with a given individual. This apparently protean character of feminist therapy is, in fact, evidence of the centrality of theory over specific application and the notion that one can harness many different applications in service of theory when the ultimate goal of the process is designed to respect the unique capacities and needs of the person seeking psychotherapy.

![]()

Theory

GOALS OF FEMINIST THERAPY

Feminist therapy has as its superordinate goal the empowerment of clients and the creation of feminist consciousness. Much of what is written in this field has to do with developing methodologies for achieving that goal in a diverse set of circumstances. The therapy relationship is construed as a setting in which, because of the norms and boundaries established by the therapist and her or his adherence to certain principles, people can experience the social environment of an egalitarian relationship. Consequently, development of egalitarian and empowering strategies that are tailored to the particular individual seeking assistance is central to feminist therapy practice. Such empowerment is seen as having the important function of subverting patriarchal influences in the lives and psyches of all of those involved in the therapy process, including the therapist. Because both parties, therapist and client alike, are immersed in patriarchal cultures, the process of uncovering disempowerment and developing strategies toward empowerment is ongoing, with each feminist therapist discovering the deep and subtle ways in which patriarchal assumptions of hierarchy and privilege inform her or his work and the experience of the people who come into the office.

A feminist therapist continuously asks, “What are the power dynamics in this situation? Where am I taking patriarchal assumptions for granted as true?” The answer to these questions might be something as deceptively simple as including a commentary about gender and social class in an assessment report about learning disabilities to unpack the effects of those variables on the problems being evaluated. Or it might be something as complex and subtle as unpacking the minutiae of power dynamics in the arrangement of office furniture to enhance feelings of equality among those participating in therapy or questioning whether the word client is itself inherently disempowering (Brown, 2006).

Feminist therapy as a model does not have specific treatment goals as do many other psychotherapies. Instead, the outcomes of treatment, which represent empowerment for the individual client, are determined collaboratively and assessed via client satisfaction and self-report. Feminist therapists ask clients about their goals and propose ways of meeting those goals; therapist and client discuss, negotiate, and renegotiate these agreements, formally and informally, throughout the course of psychotherapy. When clients do not know their goals, the goal of therapy becomes uncovering the client’s wishes; feminist therapists do not use the absence of client knowledge of needs and desires as a cue to impose their own sense of what the goals of therapy ought to be.

This client-focused model of determining the defining characteristics of good outcomes and the effectiveness of therapy places feminist therapy in close relationship with other paradigms such as person-centered, narrative, and multicultural, which place power to define outcome in clients’ hands as one piece of a larger strategy of client empowerment within the therapy relationship itself. This stance challenges the social construction of outcome as something measured by therapists or predetermined by the treatment approach. It makes clients the authorities. Rather than measuring outcome with an instrument whose scales are determined by an expert’s decision as to what is an important change in therapy, feminist therapists ask their clients to say what has changed for them and how those changes matter to them, a qualitative, phenomenological, and client driven, rather than quantitative and expert driven, methodology for assessing outcome.

Because feminist therapy conceptualizes human experience as taking place in four realms of power—somatic, intrapersonal/intrapsychic, intrapersonal/social-contextual, and spiritual/existential, all in constant exchange and interaction (see Table 3.1)—disempowerment and empowerment are seen as potentially occurring in any and all of these axes. Feminist therapy consequently defines power, not simply in the usual sense of control of other humans and/or resources, but in a manner identifying the locations, behavioral and intrapsychic, where patriarchal cultures lead people to experience powerlessness and power. Bias, stereotype, and oppression all constitute social forces that create disempowerment; they can be enacted in the large context of society or culture, the smaller context of family and community, and intrapsychically, internalized and felt as a part of self. Disempowerment and the consequences of powerlessness are construed as central sources of emotional distress and behavioral dysfunction. Feminist therapy asks, in general and in specific, what might constitute a move toward power for a given person in the domains where powerlessness has been experienced. The feminist therapist is tasked with the cocreation, with her or his client, of strategies that will invite and support empowerment for each person.

Table 3.1

The Biopsychosocial/Spiritual–Existential Axes of Personal Power

Table 3.1

The Biopsychosocial/Spiritual–Existential Axes of Personal Power (Continued)

POWER AND ITS MANY FACES

Power in the Somatic/Biological Realm

Power can be categorized into the four axes of the biopsychosocial/spiritual–existential model. Thus, in the biological realm, power means being in contact with one’s body. Power in the bodily realm means that the body is experienced as a safe place and accepted as it is rather than forced to be larger or smaller than it would be if adequately nourished. If its size or shape creates a lack of safety for a person, change of size or shape happens in the service of safety, which is a form of power, or other paths to safety that do not require modification of the body are considered. Power in the body means connection with bodily desires for food, comfort, sexual pleasure, and rest. It also entails access to means of meeting those needs that do not lead to intentional harm to one’s own body or that of others and that do not routinely violate a person’s values. Note that power in the body does not require the ability to see, hear, walk, or talk, nor is a powerful body necessarily free of pain or illness, nor strong or physically fit. Rather, empowerment at the biological level has to do with the psychosocial/spiritual relationship of self to embodiment and with the creation of a stance of compassion, acceptance, and advocacy, as needed, for one’s embodied experiences.