- •Overcoming Your Workplace Stress

- •Overcoming Your Workplace Stress

- •Martin r. Bamber

- •About the author

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •The ‘fight or flight’ response

- •Harmful stress

- •The consequences of harmful stress on the individual

- •The consequences of harmful stress for the organization

- •Conceptualizing stress

- •The ‘camera analogy’

- •The emergency response

- •Changes in thinking

- •Changes in motivation

- •Changes in emotion

- •Changes in behaviour

- •The development of stress syndromes

- •Dispelling some myths about stress

- •Answers for the stress quiz (Table 1.1) Statement 1

- •Statement 2

- •Statement 3

- •Statement 4

- •Statement 5

- •Statement 6

- •Statement 7

- •Statement 8

- •Statement 9

- •Statement 10

- •Statement 11

- •Statement 12

- •Statement 13

- •Statement 14

- •Statement 15

- •Statement 16

- •How well did you do in the quiz?

- •How stressed are you?

- •A stress checklist

- •Scoring and interpreting the checklist (Table 1.2)

- •Summary

- •Chapter 2

- •Identifying the causes of your occupational stress

- •Introduction

- •An overview of the causes of occupational stress

- •Individual factors

- •Genetic/inherited factors

- •Acquired/learned factors

- •Personality/trait factors

- •Factors in the work environment

- •Job demands

- •Physical working conditions

- •Control

- •Supports

- •Relationships

- •Pay and career prospects

- •The home–work interface

- •The employer’s ‘duty of care’ to provide a healthy working environment Case study: Schmidt

- •The impact of employment legislation

- •Demands

- •Control

- •Support

- •Relationships

- •Further developments in management standards

- •Identifying the main causes of stress in your own working environment

- •Interpreting the results of your questionnaire (Table 2.1)

- •Interpreting individual items

- •Interpretation of subscales

- •Summary and main learning points from Part I

- •About Part II of this book

- •Primary level interventions

- •Secondary level interventions

- •Tertiary level interventions

- •Doing a job analysis

- •Case study: Tony

- •The benefits of doing a job analysis

- •Interventions aimed at reducing the demands of your job Reducing the volume of work

- •Enlarging your job

- •Enriching your job

- •Improving your physical working environment

- •Interventions aimed at increasing the control you have over your job

- •Interventions aimed at increasing the supports you have at work

- •Interventions aimed at improving working relationships

- •Gather evidence

- •Find allies to support you

- •Stand up to the bully

- •Present the bully with the evidence

- •Be prepared for the backlash

- •Take things further if necessary

- •Interventions aimed at clarifying your role at work

- •Interventions aimed at improving the way that change is managed in your workplace

- •Interventions aimed at improving the home–work interface

- •Some tips for negotiating with your employer

- •What to do if your line manager is not receptive to your plight

- •What to do if you do not get the problem resolved within your workplace organization

- •Chapter 4 Living a healthy lifestyle

- •Introduction

- •Living a healthy lifestyle

- •Regular exercise

- •Some tips for doing more exercise

- •A healthy diet

- •Some tips for eating more healthily

- •Monitoring food intake

- •Medication and other drugs

- •Alcohol

- •Some tips for reducing your alcohol intake

- •Caffeine

- •Nicotine

- •Some tips for stopping smoking

- •Sleep and rest

- •Some tips to help you sleep better

- •Summary

- •An exercise

- •Developing your own ‘Healthy Lifestyle Plan’

- •Chapter 5 Developing effective time management skills

- •Introduction

- •Case study: John

- •Case study: Peter

- •What can we learn from the case studies of John and Peter?

- •Developing effective time management skills Plan ahead

- •Be clear about what your goals are

- •Manage your diary effectively

- •Create some ‘prime time’ for yourself

- •Prepare for meetings

- •Choose the best time to tackle difficult tasks

- •Overcome procrastination

- •Case study: Jenny

- •What can we learn from the case study of Jenny?

- •Learn to delegate

- •Stay focused

- •Prioritize tasks

- •Be organized

- •Developing an action plan to manage your time more effectively

- •Chapter 6 Developing assertiveness skills What is assertiveness?

- •Why are some people unassertive?

- •What are the consequences of being unassertive?

- •Case study: Caroline

- •Case study: Rosie

- •How can you become more assertive?

- •Education

- •Aggressive behaviour

- •Submissive behaviour

- •Manipulative behaviour

- •Assertive behaviour

- •Knowing your rights

- •A ‘Bill of Rights’

- •What can we learn from the case study of Caroline?

- •Developing assertive attitudes

- •Developing assertive behaviours

- •Other useful assertiveness techniques to help you

- •Use the ‘broken record’ technique

- •Use fogging

- •Be concise

- •Be specific

- •Clarify

- •Use ‘I’ statements

- •Active listening

- •Aim for a workable compromise

- •Negative assertion

- •Empathic confrontation

- •Self-disclosure

- •How assertive are you?

- •Table 6.1 scores and interpretation Scoring of individual items

- •Interpreting the total scores for the questionnaire

- •Developing an action plan to become more assertive

- •Chapter 7 Developing effective interpersonal skills

- •Introduction

- •What are interpersonal communication skills?

- •Why are some people interpersonally less skilled than others?

- •What are the consequences of being interpersonally unskilled?

- •Developing your own interpersonal skills

- •Body posture and gestures

- •Facial expressions

- •Eye contact

- •Voice projection

- •Personal space

- •Personal appearance and presentation

- •Verbal skills

- •Paraphrasing

- •Reflecting feelings

- •Summarizing

- •Minimal encouragers

- •Asking open questions

- •Immediacy

- •Concreteness

- •The use of small talk

- •Higher level interpersonal skills

- •Developing cognitive skills

- •How interpersonally skilled are you?

- •Developing an action plan aimed at becoming more interpersonally skilled

- •Chapter 8 Developing relaxation skills

- •Introduction

- •Informal relaxation techniques

- •Semi-formal relaxation techniques

- •Massage

- •Releasing your shoulder tension

- •Soothing your scalp

- •Relaxing your eyes

- •Formal relaxation techniques

- •Deep breathing exercises

- •A deep breathing exercise

- •Progressive muscular relaxation

- •A progressive muscular relaxation exercise

- •A brief relaxation exercise for the neck and shoulders

- •Mental relaxation techniques

- •Meditation

- •Mindfulness

- •Mental refocusing

- •Visual imagery

- •Summary and main learning points

- •Chapter 9 Changing the way you relate to your work

- •Introduction

- •Understanding the links between thoughts, feelings, behaviours and bodily reactions

- •The cat vignette exercise

- •Identifying unhelpful patterns of thinking

- •Labelling dysfunctional thinking styles

- •Catastrophic thinking

- •Jumping to conclusions and mind reading

- •Overgeneralization

- •Magnification

- •Minimization

- •Personalization

- •Black and white thinking

- •‘Should’ and ‘must’ statements

- •Challenging dysfunctional patterns of thinking

- •Examining the evidence

- •Exploring the alternatives

- •Identifying advantages and disadvantages

- •The friend technique

- •Checking it out

- •Estimating probabilities

- •Reattributing meaning

- •Conducting behavioural experiments

- •Case study: Sarah

- •Challenging work dysfunctions

- •Challenging patterns of over-commitment Modifying perfectionism

- •Modifying workaholism

- •Challenging patterns of under-commitment Modifying underachievement

- •Modifying procrastination

- •Summary

- •Chapter 10 Overcoming stress syndromes

- •Introduction

- •Treating anxiety syndromes

- •Performance anxiety

- •Case study: Philip

- •Treating Philip’s performance anxiety

- •What can we learn from the case study of Philip?

- •Panic attacks

- •Case study: Andrew

- •Treating Andrew’s panic attacks

- •Phobic avoidance

- •Treating phobic avoidance

- •Case study: Maxine

- •Treating the depression syndrome

- •Challenging depressive thinking

- •Challenging unhelpful behaviours

- •Activity scheduling

- •Conducting behavioural experiments

- •A note on the burnout syndrome

- •Treating burnout syndrome

- •Treating the hostility syndrome

- •Summary

- •The eight stages of a self-help plan

- •Make a problem list

- •Prioritize your problems

- •Set your goals

- •Establish the criteria of success

- •Plan your interventions

- •Develop a self-help treatment plan

- •Monitor and review your progress

- •Prevent relapse

- •Case study: Helen

- •Making a problem list and prioritizing the problems

- •Setting the goals and establishing the criteria of success

- •Comfort eating and weight gain

- •Avoidance

- •Procrastination

- •Unassertiveness

- •Anxiety

- •Poor self-image

- •Planning the interventions

- •Interventions for comfort eating and weight gain

- •Interventions for avoidance

- •Interventions for procrastination

- •Interventions for unassertiveness

- •Interventions for anxiety

- •Interventions for poor self-image

- •Developing a self-help treatment plan

- •Monitoring and reviewing progress

- •Summary

- •Chapter 12 Summary and conclusions

- •Appendix Useful books and contacts

Checking it out

The checking it out technique is particularly useful when an individual is uncertain about what another person is thinking. This can done by simply asking people what they are thinking rather than jumping to conclusions about their motivations or mind reading. Checking things out can provide an immediate and very effective way of challenging negative assumptions.

Estimating probabilities

Estimating the probability of both negative and positive interpretations of an event is a particularly powerful technique for challenging anxious predictions. By assessing both interpretations it does not reject the original negative interpretation, unlikely as it might be, but contrasts it with more likely interpretations. This approach trains the individual to consider thoughts as interpretations of reality rather than reality itself and helps them reach more rational conclusions, the outcomes of which can then be subsequently evaluated. For example, if someone is anxious about flying, it is possible to compare the probability of having an accident while flying, to the probability of having an accident in a car, and get a sense of proportion about the risk involved.

Reattributing meaning

The technique of reattributing meaning is particularly helpful for challenging beliefs about guilt and blame. Rather than blaming oneself, the reattribution technique encourages the individual to consider external environmental factors as causes for negative outcomes rather than just internal personal factors. Also, even if the individual was responsible to some extent, they are encouraged to ask the question ‘Are the consequences of this really as bad as they seem?’ and consider how might they feel about these events in one day, one week, one month or six months’ time.

Conducting behavioural experiments

Challenging cognitive distortions need not take place only at a cognitive level. The process can be greatly enhanced by the use of some more empirical behavioural strategies such as conducting behavioural experiments for example. This involves the setting up of ‘mini experiments’, whereby the patient’s original negative thoughts and the new alternative positive ones are treated as two possible alternative hypotheses predicting an outcome. The patient is then encouraged to test these out in a real life situation and to establish which of the two alternatives is more accurately predictive of the outcome.

Case study: Sarah

This case study has been included to illustrate the use of the cognitive techniques described above to identify, label and challenge dysfunctional thinking patterns.

Sarah was a 32-year-old nurse who had just been promoted to a post as a nurse in charge of an intensive care unit. It was the week before she was due to start in her new job and she was feeling particularly anxious about it. As a result of her early life experiences and upbringing, Sarah was not a very confident individual and was prone to experiencing quite a lot of self-doubt and worry about her own capabilities, even though she was in reality quite a high achiever. As the start date got nearer, she became increasingly anxious, verging on panicky. Sarah was encouraged to commence a thoughts diary in order to identify the unhelpful thinking patterns which were leading to her feeling anxious and panicky. A copy of one of the entries in her thoughts dairy is provided in Table 9.4.

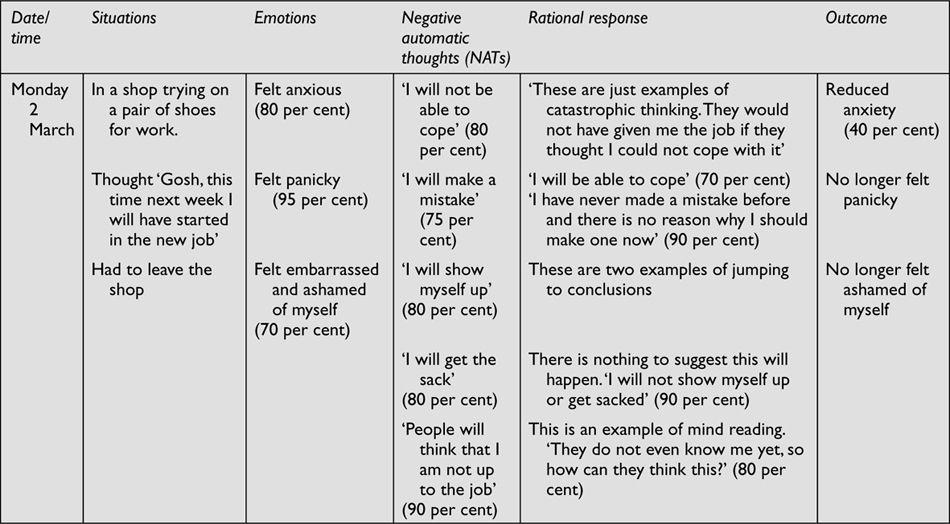

Table 9.4 An example of Sarah’s thoughts diary

The example in the thoughts diary reported that Sarah had experienced an anxiety attack in a shoe shop and had to leave the shop because of it. The triggering event was identified as attempting to buy a pair of shoes for starting her new job the following week. The triggering thought which led to her anxiety was ‘Gosh, this time next week I will have started in the new job’. Through the process of self-monitoring her thoughts using a thoughts diary, Sarah was able to identify and rate a number of dysfunctional thoughts associated with her anxiety. These included ‘I will not be able to cope’ (80 per cent), ‘I will make a mistake’ (75 per cent), ‘I will show myself up’ (80 per cent), ‘I will get the sack’ (80 per cent) and ‘People will think that I am not up to the job’ (90 per cent). She labelled these distortions as examples of catastrophic thinking, jumping to conclusions and mind reading. By looking at the evidence for and against each of the NATs listed, Sarah was able to identify alternative more positive and rational beliefs to challenge them. As a consequence of successfully challenging her anxious thinking patterns Sarah’s overall level of anxiety reduced considerably and she felt more able to cope.

In addition, Sarah set up a behavioural experiment to test her positive and negative predictions about her new job. Her positive predictions were those beliefs she had reached through the process of challenging her NATs that she would be able to cope, would not get sacked, would not make a mistake or show herself up, and that people would think that she was capable of doing the job. Her negative predictions were that she would not cope, that she would get the sack, make a mistake or show herself up, and people would think she was not up to the job. She tested out the accuracy of these predictions two months after commencing her new job and the outcome was that the evidence completely supported her positive predictions and invalidated the negative ones. Not only had she settled well in her new job, but also she had not made any significant mistakes and had received lots of positive comments about her performance at work from her manager, colleagues and patients. For Sarah, the behavioural experiment had provided evidence that she was more capable than she had initially believed and it disconfirmed her original negative beliefs about herself and others. As a result of the positive outcome of the experiment, she began to feel more confident and relaxed at work.