- •Overcoming Your Workplace Stress

- •Overcoming Your Workplace Stress

- •Martin r. Bamber

- •About the author

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •The ‘fight or flight’ response

- •Harmful stress

- •The consequences of harmful stress on the individual

- •The consequences of harmful stress for the organization

- •Conceptualizing stress

- •The ‘camera analogy’

- •The emergency response

- •Changes in thinking

- •Changes in motivation

- •Changes in emotion

- •Changes in behaviour

- •The development of stress syndromes

- •Dispelling some myths about stress

- •Answers for the stress quiz (Table 1.1) Statement 1

- •Statement 2

- •Statement 3

- •Statement 4

- •Statement 5

- •Statement 6

- •Statement 7

- •Statement 8

- •Statement 9

- •Statement 10

- •Statement 11

- •Statement 12

- •Statement 13

- •Statement 14

- •Statement 15

- •Statement 16

- •How well did you do in the quiz?

- •How stressed are you?

- •A stress checklist

- •Scoring and interpreting the checklist (Table 1.2)

- •Summary

- •Chapter 2

- •Identifying the causes of your occupational stress

- •Introduction

- •An overview of the causes of occupational stress

- •Individual factors

- •Genetic/inherited factors

- •Acquired/learned factors

- •Personality/trait factors

- •Factors in the work environment

- •Job demands

- •Physical working conditions

- •Control

- •Supports

- •Relationships

- •Pay and career prospects

- •The home–work interface

- •The employer’s ‘duty of care’ to provide a healthy working environment Case study: Schmidt

- •The impact of employment legislation

- •Demands

- •Control

- •Support

- •Relationships

- •Further developments in management standards

- •Identifying the main causes of stress in your own working environment

- •Interpreting the results of your questionnaire (Table 2.1)

- •Interpreting individual items

- •Interpretation of subscales

- •Summary and main learning points from Part I

- •About Part II of this book

- •Primary level interventions

- •Secondary level interventions

- •Tertiary level interventions

- •Doing a job analysis

- •Case study: Tony

- •The benefits of doing a job analysis

- •Interventions aimed at reducing the demands of your job Reducing the volume of work

- •Enlarging your job

- •Enriching your job

- •Improving your physical working environment

- •Interventions aimed at increasing the control you have over your job

- •Interventions aimed at increasing the supports you have at work

- •Interventions aimed at improving working relationships

- •Gather evidence

- •Find allies to support you

- •Stand up to the bully

- •Present the bully with the evidence

- •Be prepared for the backlash

- •Take things further if necessary

- •Interventions aimed at clarifying your role at work

- •Interventions aimed at improving the way that change is managed in your workplace

- •Interventions aimed at improving the home–work interface

- •Some tips for negotiating with your employer

- •What to do if your line manager is not receptive to your plight

- •What to do if you do not get the problem resolved within your workplace organization

- •Chapter 4 Living a healthy lifestyle

- •Introduction

- •Living a healthy lifestyle

- •Regular exercise

- •Some tips for doing more exercise

- •A healthy diet

- •Some tips for eating more healthily

- •Monitoring food intake

- •Medication and other drugs

- •Alcohol

- •Some tips for reducing your alcohol intake

- •Caffeine

- •Nicotine

- •Some tips for stopping smoking

- •Sleep and rest

- •Some tips to help you sleep better

- •Summary

- •An exercise

- •Developing your own ‘Healthy Lifestyle Plan’

- •Chapter 5 Developing effective time management skills

- •Introduction

- •Case study: John

- •Case study: Peter

- •What can we learn from the case studies of John and Peter?

- •Developing effective time management skills Plan ahead

- •Be clear about what your goals are

- •Manage your diary effectively

- •Create some ‘prime time’ for yourself

- •Prepare for meetings

- •Choose the best time to tackle difficult tasks

- •Overcome procrastination

- •Case study: Jenny

- •What can we learn from the case study of Jenny?

- •Learn to delegate

- •Stay focused

- •Prioritize tasks

- •Be organized

- •Developing an action plan to manage your time more effectively

- •Chapter 6 Developing assertiveness skills What is assertiveness?

- •Why are some people unassertive?

- •What are the consequences of being unassertive?

- •Case study: Caroline

- •Case study: Rosie

- •How can you become more assertive?

- •Education

- •Aggressive behaviour

- •Submissive behaviour

- •Manipulative behaviour

- •Assertive behaviour

- •Knowing your rights

- •A ‘Bill of Rights’

- •What can we learn from the case study of Caroline?

- •Developing assertive attitudes

- •Developing assertive behaviours

- •Other useful assertiveness techniques to help you

- •Use the ‘broken record’ technique

- •Use fogging

- •Be concise

- •Be specific

- •Clarify

- •Use ‘I’ statements

- •Active listening

- •Aim for a workable compromise

- •Negative assertion

- •Empathic confrontation

- •Self-disclosure

- •How assertive are you?

- •Table 6.1 scores and interpretation Scoring of individual items

- •Interpreting the total scores for the questionnaire

- •Developing an action plan to become more assertive

- •Chapter 7 Developing effective interpersonal skills

- •Introduction

- •What are interpersonal communication skills?

- •Why are some people interpersonally less skilled than others?

- •What are the consequences of being interpersonally unskilled?

- •Developing your own interpersonal skills

- •Body posture and gestures

- •Facial expressions

- •Eye contact

- •Voice projection

- •Personal space

- •Personal appearance and presentation

- •Verbal skills

- •Paraphrasing

- •Reflecting feelings

- •Summarizing

- •Minimal encouragers

- •Asking open questions

- •Immediacy

- •Concreteness

- •The use of small talk

- •Higher level interpersonal skills

- •Developing cognitive skills

- •How interpersonally skilled are you?

- •Developing an action plan aimed at becoming more interpersonally skilled

- •Chapter 8 Developing relaxation skills

- •Introduction

- •Informal relaxation techniques

- •Semi-formal relaxation techniques

- •Massage

- •Releasing your shoulder tension

- •Soothing your scalp

- •Relaxing your eyes

- •Formal relaxation techniques

- •Deep breathing exercises

- •A deep breathing exercise

- •Progressive muscular relaxation

- •A progressive muscular relaxation exercise

- •A brief relaxation exercise for the neck and shoulders

- •Mental relaxation techniques

- •Meditation

- •Mindfulness

- •Mental refocusing

- •Visual imagery

- •Summary and main learning points

- •Chapter 9 Changing the way you relate to your work

- •Introduction

- •Understanding the links between thoughts, feelings, behaviours and bodily reactions

- •The cat vignette exercise

- •Identifying unhelpful patterns of thinking

- •Labelling dysfunctional thinking styles

- •Catastrophic thinking

- •Jumping to conclusions and mind reading

- •Overgeneralization

- •Magnification

- •Minimization

- •Personalization

- •Black and white thinking

- •‘Should’ and ‘must’ statements

- •Challenging dysfunctional patterns of thinking

- •Examining the evidence

- •Exploring the alternatives

- •Identifying advantages and disadvantages

- •The friend technique

- •Checking it out

- •Estimating probabilities

- •Reattributing meaning

- •Conducting behavioural experiments

- •Case study: Sarah

- •Challenging work dysfunctions

- •Challenging patterns of over-commitment Modifying perfectionism

- •Modifying workaholism

- •Challenging patterns of under-commitment Modifying underachievement

- •Modifying procrastination

- •Summary

- •Chapter 10 Overcoming stress syndromes

- •Introduction

- •Treating anxiety syndromes

- •Performance anxiety

- •Case study: Philip

- •Treating Philip’s performance anxiety

- •What can we learn from the case study of Philip?

- •Panic attacks

- •Case study: Andrew

- •Treating Andrew’s panic attacks

- •Phobic avoidance

- •Treating phobic avoidance

- •Case study: Maxine

- •Treating the depression syndrome

- •Challenging depressive thinking

- •Challenging unhelpful behaviours

- •Activity scheduling

- •Conducting behavioural experiments

- •A note on the burnout syndrome

- •Treating burnout syndrome

- •Treating the hostility syndrome

- •Summary

- •The eight stages of a self-help plan

- •Make a problem list

- •Prioritize your problems

- •Set your goals

- •Establish the criteria of success

- •Plan your interventions

- •Develop a self-help treatment plan

- •Monitor and review your progress

- •Prevent relapse

- •Case study: Helen

- •Making a problem list and prioritizing the problems

- •Setting the goals and establishing the criteria of success

- •Comfort eating and weight gain

- •Avoidance

- •Procrastination

- •Unassertiveness

- •Anxiety

- •Poor self-image

- •Planning the interventions

- •Interventions for comfort eating and weight gain

- •Interventions for avoidance

- •Interventions for procrastination

- •Interventions for unassertiveness

- •Interventions for anxiety

- •Interventions for poor self-image

- •Developing a self-help treatment plan

- •Monitoring and reviewing progress

- •Summary

- •Chapter 12 Summary and conclusions

- •Appendix Useful books and contacts

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank everyone who has either indirectly or directly made a contribution to the writing of this book. This includes work colleagues past and present with whom I have shared my ideas, and also my patients, who have been the source of much of the clinical material contained in this book. I would also like to thank the publishers for giving me the opportunity to write this book and in particular the editorial team for their support and guidance through to its completion.

Part I

Understanding occupational stress

Chapter 1

Occupational stress and its consequences

In order that people may be happy in their work, these three things are needed: They must be fit for it. They must not do too much of it. And they must have a sense of success in it.

(John Ruskin 1819–1900)

Normal stress

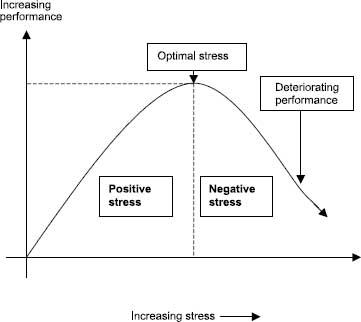

When reading the literature about stress it would be easy to conclude that it has universally negative consequences and that it is something that needs to be eradicated from all areas of our lives. However, it is important to emphasize from the outset of this book that not all stress is bad for us. A certain degree of stress is a natural, normal and unavoidable part of everyday life. For example, most of us can relate to the stress we have experienced when we have been about to take an exam, do our driving test, or give a presentation to managers or colleagues at work. This is known as positive stress, because it motivates us to do well and can actually enhance our performance on the task in hand. With positive stress the individual is motivated to meet the challenge and ultimately experiences a sense of achievement at having successfully mastered it (as acknowledged in the quote by John Ruskin above). This normal type of stress does not have any lasting consequences and if successfully managed, it can result in an increased sense of competence, fulfilment and wellbeing. There is an evolutionary explanation for this kind of stress in that our ancestors’ reactions to perceived threats and dangers had survival value. For example, in primitive society, hunter-gatherers would on occasions risk their lives in the hunt for food or to defend their community. In doing so, they would experience dangers which would have triggered the body’s stress response. This in turn would have prepared the individual for action, either to fight or to escape the threat. In modern societies and cultures, however, the stressors experienced are not usually life threatening in the way that they were for our ancestors, but they still trigger the stress response. The relationship between stress and performance is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The stress–performance curve.

It can be seen on the left hand side of the graph in Figure 1.1 that low to moderate levels of stress actually serve to enhance performance until the optimal level is reached. However, once the level of stress exceeds the optimal level, there is a rather rapid and steep decline in performance and it is this that is described as negative stress.