- •Chapter 13 the global economy

- •13.1. The Benefits of Trade

- •13.2. The Barriers to International Trade

- •13.3. Why Nations Restrict International Trade

- •13.4. The Argument in Favor of Free Trade

- •13.5. Promoting Economic Cooperation

- •13.6. Financing International Trade

- •13.7. The u.S. Balance of Payments

- •13.8. Balance of Payments Problems

13.7. The u.S. Balance of Payments

The flow of trade between the United States and the rest of the world affects everyone. For that reason economists keep close tabs on international trade, and they have developed several accounting tools to track the global economy. You will frequently hear or see stories in the news about two of these tools-the balance of trade and the balance of payments.

The balance of trade is the difference between the value of a nation's imports and exports. When a nation exports more goods than it imports, it has a positive balance of trade. In recent years the United States has imported more goods than it exported and has a negative balance of trade. The balance of trade is part of a much more complicated accounting tool called the balance of payments. It includes exchanges of merchandise plus transactions involving services, international loans, interest, dividends, and gold reserves. Just as business firms summarize the results oftheir operations in profitt-and-loss statements, economists summarize the flow of international transactions in the balance of payments. International transactions result in the flow of U.S.-held foreign currencies or dollars in and out of the country. Importing goods, investment in a foreign corporation, or a cash gift to a relative in Liberia are examples of transactions that would result in a flow of funds out of the U.S. Exporting goods, investment by foreigners in American corporations, or a cash gift to you from a relative in Morocco would result in a flow of funds into the country.

At the end of each year more funds will have flowed into this country from other countries than flowed out, or vice versa. It is at this point that the "balance" is put into the balance of payments. If foreigners have spent more dollars in the U.S. than Americans have spent overseas, the Federal Reserve can make up the difference by exchanging its dollars for foreign currencies. In this way, the Fed is able to help stabilize the value of the dollar.

If, on the other hand, Americans have spent more dollars in other countries than the United States received, the Fed will make up the difference by exchanging foreign currencies in its accounts for the excess dollars in foreign bank accounts.

13.8. Balance of Payments Problems

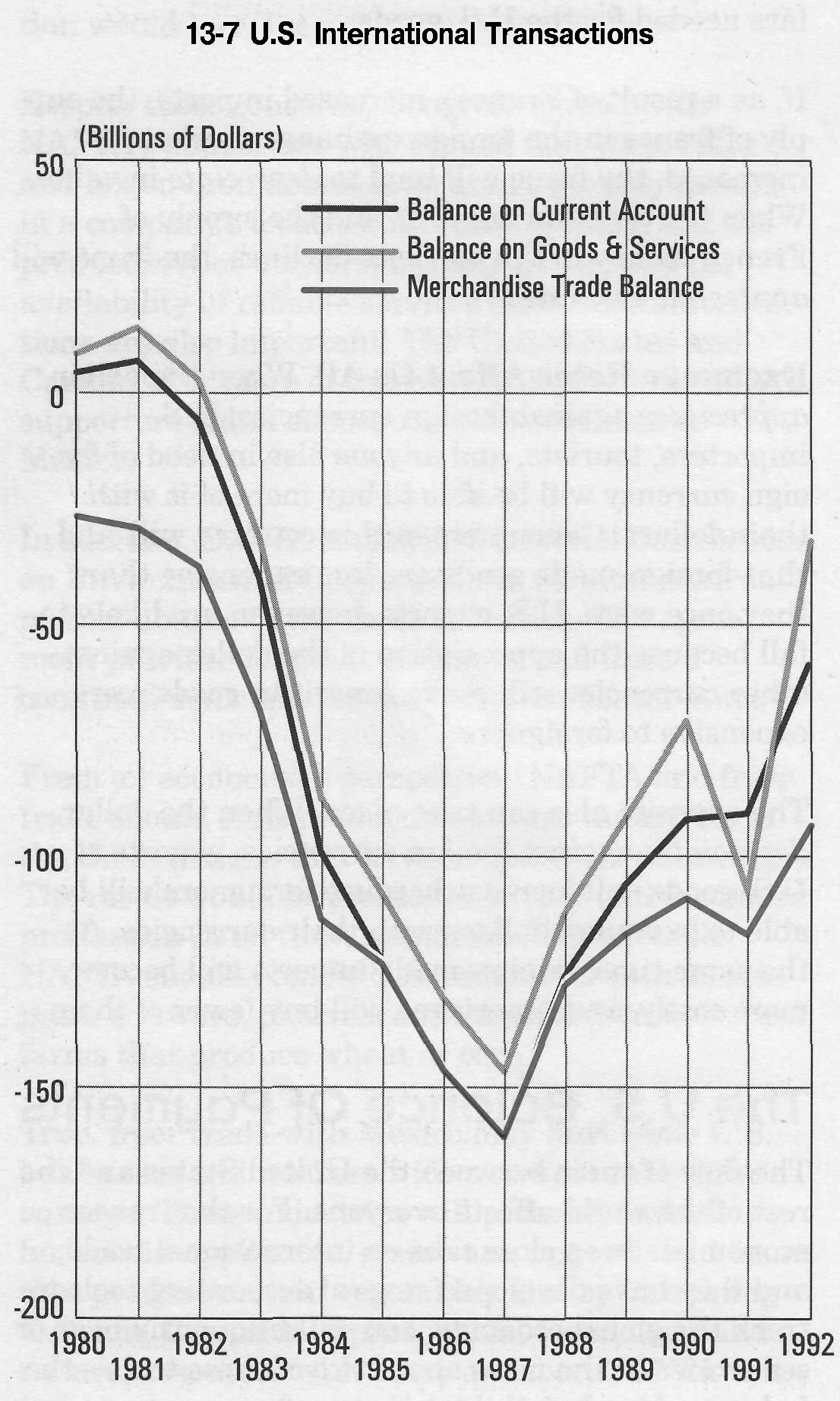

Over the last 10 years the United States has been troubled by a persistent deficit in its merchandise trade balance. This means that more dollars have been spent by Americans to pay for foreign goods than have been spent by foreigners to purchase American products. (See Figure 13-7.) This is probably not desirable. However, due to the overall size and strength of the U.S. economy, the effects of these deficits have not been as serious as they could have been.

When more dollars flow out of the country than flow back in, foreigners are left holding the difference. Those holding the dollars can do two things with them-exchange them for other currencies or hold on to them. As long as foreigners are willing to hold American dollars, things remain stable. Exchanging dollars for other currencies, however, puts pressure on the U.S. economy to make that currency available to them. The effect of such pressure is to depreciate the value of the dollar and increase the cost of foreign goods and services to Americans.

Between 1980 and 1985 the most serious balance of payments problem was caused by the dollar's appreciation. Foreigners were eager to acquire and hold dollars even though Americans imported far more goods and services than they exported. ($12.1 billion more in 1985; see Figure 13-7). There were two main reasons for this.

First, people around the world had confidence in the United States. Many foreigners believed the dollar was a safer currency than their own. So, they exchanged their currencies for dollars.

Second, U.S. interest rates were high compared to rates in other countries. To profit from those high interest rates, foreign investors deposited dollars in American banks and invested in American securities. Thus, owning dollars was doubly attractive to foreigners. The dollar was the world's safest currency, and it paid a handsome return on investments.

Between 1985 and 1987, the U.S. government and other nations, especially Germany and Japan, attempted to stop the appreciation of the dollar. While the techniques used to achieve that goal are complicated, the results of the effort are illustrated in Table 13-6. As you can see, the dollar depreciated substantially with respect to the currencies of Austria, Canada, France, West Germany, and Switzerland between 1984 and 1992. It also depreciated against other currencies. This made U.S. products and services relatively less expensive than they had been. As a result, U.S. exports increased dramatically and the trade deficit declined.

Events affecting the American economy have a direct effect on the behavior of people around the globe. But this ought not to be surprising, for as noted here, all nations today are part of a global economy.

Summary

Trade among nations takes place for the same reasons that it does within a nation-to obtain goods and services a region cannot produce itself, or to obtain them at a lower cost than they could be produced at home. This is explained by the principle of comparative advantage, which states that as long as the opportunity costs to produce items differ between two nations, both will profit by specializing in those things that they produce most efficiently and by exchanging their surpluses.

Despite the advantage of international trade, most nations have erected artificial barriers to that trade to protect "infant" and essential industries from foreign competition. These barriers are usually in the form of tariffs or quotas. In recent years, however, the trend has been toward lowering tariffs and other barriers to trade.

Imports must be paid for in a currency that is acceptable to the seller. In order to make these transactions easier, there is a market for the currencies of all trading nations. The selling price of one nation's currency in terms of the currencies of other nations is known as its "exchange rate." Exchange rates fluctuate according to the laws of supply and demand.

When the value of a nation's currency is decreasing in terms of other currencies, its exports are likely to increase because they will be less expensive to people in foreign countries. Imports, in these circumstances, are likely to decrease because foreign goods will become more expensive. When a nation's currency is appreciating in terms of other currencies, the opposite is likely to occur.

The balance of payments summarizes the transactions that have taken place in international trade over a given period of time, usually one year. Economists look to the balance of payments for clues to future trends in the value of a nation's currency and other consequences of its foreign trade.

Reading for Enrichment

The Tariff Issue In American History

Should the United States impose a tax on imports? If so, at what level? Such questions have been disputed throughout American history. Debate over tariffs emerged at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Representatives from Northern and Middle states supported the idea of a tax on foreign products sold in the U.S. Manufacturers knew that a high tariff would raise the price of imported goods, forcing consumers to buy American goods instead. But the nonindustrial South opposed the tax; it did not want to pay higher prices for goods. The North and South compromised at the Convention, but the issue would be raised again.

Indeed, in 1828 when Congress passed a high protective tariff, Southern leaders denounced it as a "Tariff of Abominations." The dispute almost led to civil war when South Carolina declared it would not obey the new law. Some Carolinians spoke of seceding from the Union. President Andrew Jackson was prepared to use troops to enforce federal law in South Carolina. The crisis ended without bloodshed when both sides accepted a new tariff that gradually decreased rates.

Congress approved high tariffs during the Civil War in order to protect American industry. Duties on imports rose even higher in 1890 with the McKinley Tariff, which effectively eliminated foreign competition. Progressives denounced those rates because they forced consumers to pay higher prices for manufactured goods. The Payne-Aldrich Tariff of 1909 helped lower rates, but the tax on most imported goods remained high.

President Woodrow Wilson called for lower tariffs when he was elected in 1912. He believed that by eliminating foreign competition with high tariffs, U.S. monopolies were created. So Congress passed the Underwood Tariff, the first real reduction in rates since the Civil War. But import duties rose again after World War I. In fact, the Hawley-Smoot Act of 1930 issued the highest tariff in American history. Some economists today cite the act as a cause of the Great Depression. If not a root cause, it certainly made the depression worse. For example, the increased duties prevented foreign countries from selling their goods in American markets. With their principal source of dollars cut off, those nations were unable to repay the money they had borrowed from the U.S. to fight the war. Other nations retaliated by raising their tariffs, further hurting American trade.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried to remedy the situation. The Trade Agreement Act (or Reciprocal Trade Act) of 1934 contained a "most-favored nation" clause, which offered any country the opportunity to receive "most-favored" treatment in any tariff agreement if it did the same for the United States. This legislation reduced import duties and greatly increased American trade with specific countries.

In 1947 the United States and 22 other nations signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Since then the number of GATT nations has grown to 132. The main purpose of GATT is to reduce tariffs and other trade restrictions through multilateral negotiations-face-to-face discussions among nations' leaders.

Since its founding, the organization has held nearly 10 "rounds" of negotiations. The Trade Expansion Act of 1962 gave the president power to reduce tariffs. This was accomplished during the Kennedy Round (1963-67) and the Tokyo Round (1973-79). As a result of these negotiations, average U.S. tariffs have been reduced to 4.4 percent. This trend continued in the Uruguay Round, which began in 1986 and was completed in December 1993.

Protectionism, however, remains a sensitive issue. Foreign competition, particularly in the steel and automobile industries, has created some economic hardship in the United States. Manufacturers and workers in affected industries argue that it is necessary to restrict foreign competition. They feel that without such protection, their products will be undersold, and they will be forced out of business.

Those opposed to protectionism argue that because of barriers, consumers must pay more for automobiles and many other products. They also say that with less foreign competition, automobile and steel manufacturers are less inclined to improve productivity and product quality.

The History of Economic Thought

David Ricardo (1772-1823) Classical Champion of Free Trade

Born in England, David Ricardo made a fortune on the London Stock Exchange. This wealth gave him the time to write and to serve in Parliament's House of Commons. His most famous work, Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), marked him as the most influential spokesman for classical economics since Adam Smith.

Ricardo is especially famous in international economics for demonstrating the advantages of free trade. Free trade is a policy in which tariffs and other barriers to trade between nations are removed. To prove his point, Ricardo developed the principle of comparative advantage. It demonstrates how one nation might profitably import goods from another even though the importing country could produce that item for less than the exporter.

Ricardo's explanation of comparative advantage went as follows:

Portugal and England, both of whom produce wine and cloth, are considering the advantages of exchanging those products with one another. Let's assume that:

• x barrels of wine are equal to (and therefore trade evenly for) у yards of cloth.

• In Portugal 80 workers can produce x barrels of wine in a year. It takes 120 English workers to produce that

many barrels.

• 90 Portuguese workers can produce у yards of cloth in a year. It takes 100 English workers to produce у yards of

cloth.

We can see, Ricardo continued, that even though Portugal can produce both wine and cloth more efficiently than England, it pays them to specialize in the production of wine and import English cloth. This is so because by trading with England, Portugal can obtain as much cloth for 80 worker-years as it would take 90 worker-years to produce themselves.

England will also benefit. By specializing in cloth, it will be able to obtain wine in exchange for 100 worker-years of labor rather than 120.

As a member of Parliament, Ricardo pressed the government to abandon its policy of protection. Though he did not live to achieve that goal, his efforts bore fruit in the 1840s when England became the first industrial power to adopt a policy of free trade. Then 70 years of economic growth followed, during which the nation became the world's wealthiest industrial power.