- •Chapter 13 the global economy

- •13.1. The Benefits of Trade

- •13.2. The Barriers to International Trade

- •13.3. Why Nations Restrict International Trade

- •13.4. The Argument in Favor of Free Trade

- •13.5. Promoting Economic Cooperation

- •13.6. Financing International Trade

- •13.7. The u.S. Balance of Payments

- •13.8. Balance of Payments Problems

13.6. Financing International Trade

Have you ever traveled to another country? If so, you have probably noticed that some hotels, stores, and restaurants don't want your dollars, quarters, dimes, or nickels. Just about every nation has its own form of money. Sellers in each country expect to be paid in their own currency for the goods they sell to other countries. As a result, exporters and importers must be able to exchange currencies easily and efficiently.

Exchange rates and the foreign exchange market. Foreign currencies (or foreign exchange) are bought and sold by currency dealers and banks around the country. These bankers and currency dealers make up the foreign exchange market.

Exchange rates were not always determined in this manner. From 1944 until the 1970s most nations operated under a system of fixed exchange rates. That is, they agreed to exchange their currency for any other foreign currency at an established rate. In most instances, the fixed rate of exchange was expressed in dollars. In other words, the French would exchange their francs at the rate of five to the dollar; the Swiss at the rate of four, and so on. Likewise, the U.S. government agreed to exchange dollars for foreign currencies or gold at a fixed rate of exchange.

By 1971 so many dollars were held by foreigners that it was impossible for the United States to guarantee to trade them for gold. At that point President Nixon announced that the dollar was no longer "convertible" into gold, and that its value would be determined by the laws of supply and demand.

President Nixon was saying that dollars, francs, pesos, and any other currency were really commodities like soybeans and hog bellies that could be traded in foreign exchange markets. Exchange rates would be determined by the laws of supply and demand.

Following the United States' lead, most nations around the globe abandoned the old system in favor of what came to be called "flexible exchange rates." That is, they allowed the value of their currencies to be determined by the laws of supply and demand in foreign exchange markets rather than government agencies.

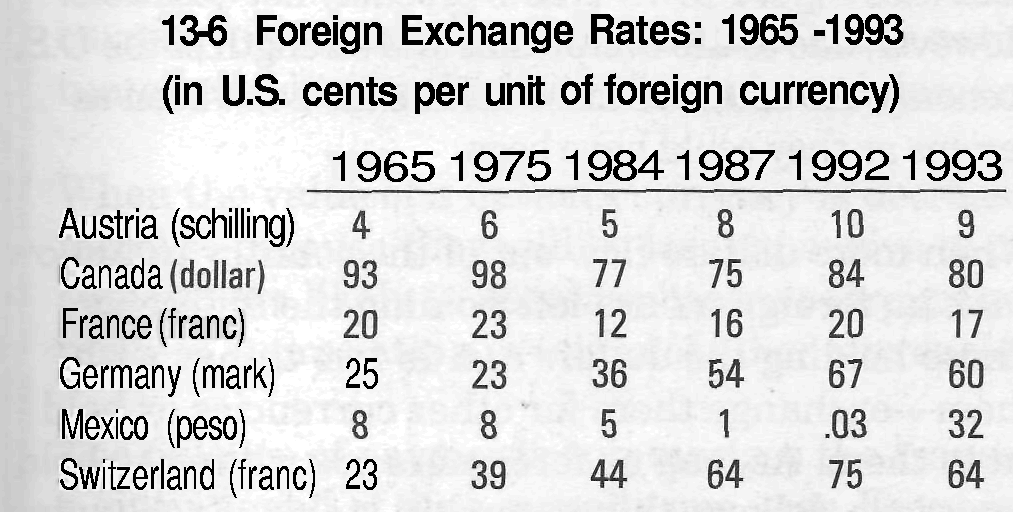

Why Do Exchange Rates Change? As Table 13-6 shows, exchange rates are flexible over time. The Mexican peso has depreciated-fallen in value-against the dollar. In 1975 a peso was worth 8 cents; in 1992 it was worth .03 cents. To put it another way, in 1975 one dollar would buy 12.5 pesos; in 1992 one dollar bought 3,333 pesos. In fact, pesos depreciated so much that the Mexican government decided to revalue them. In January 1993 pesos were reissued so that one dollar bought 3.1 pesos. By contrast, the Swiss franc appreciated-rose in value-against the dollar, rising from a value of 23 cents in 1965 to a high of 75 cents in 1992.

Currencies fluctuate in value because of the laws of supply and demand. The demand for a nation's currency is usually a result of the demand for its goods and services. If people in the United States are buying more goods and services from Canada, they will need additional Canadian dollars. This increased demand will raise the price of Canadian currency. Similarly, if Americans want fewer Austrian goods and services, the decreasing demand for the Austrian schilling will reduce the price of that currency.

The supply of foreign exchange increases and decreases as one country's citizens use their currency to purchase currency from another whose goods they want to buy. For example, French importers seeking to buy U.S. goods will have to trade their francs in the foreign exchange markets for the dollars needed for the U.S. goods.

If, as a result of France's increased imports, the supply of francs in the foreign exchange markets is increased, the franc will tend to depreciate in value. When the opposite happens and the supply of French money in the markets declines, the franc will appreciate in value.

Exchange Rates Affect Us All. When the dollar appreciates against foreign currencies, U.S. importers, tourists, and anyone else in need of foreign currency will be able to buy more of it with their dollars. Consumers in this country will find that foreign-made goods are less expensive than they once were. U.S. exports, however, are likely to fall because the appreciation of the dollar against other currencies will make American goods more expensive to foreigners.

The opposite also can take place. When the dollar depreciates against foreign currencies, exports of U.S. goods will increase because foreigners will be able to buy more dollars with their currencies. At the same time, foreign-made imports will become more costly, and Americans will buy fewer of them.