- •Chapter 13 the global economy

- •13.1. The Benefits of Trade

- •13.2. The Barriers to International Trade

- •13.3. Why Nations Restrict International Trade

- •13.4. The Argument in Favor of Free Trade

- •13.5. Promoting Economic Cooperation

- •13.6. Financing International Trade

- •13.7. The u.S. Balance of Payments

- •13.8. Balance of Payments Problems

Chapter 13 the global economy

The American standard of living has never been higher than it is today. Credit for this abundance must be given to the political, social, and economic systems that allow us to enjoy many goods and services from here and abroad.

The preceding 12 chapters have emphasized how the U.S. economy provides for the production and distribution of the goods and services produced in the United States. But the truth is the United States is part of a global economy. Many of the things you use and enjoy every day were made in other countries. In the global economy, goods and services are exchanged across national boundaries in a process described as "international trade." Goods and services purchased from other countries are imports. Goods and services U.S companies sell to other countries are exports.

"It's amazing! We had an assignment the other day to write a four- or five-line description of what we did before we got to school. The teacher called it The World in My House/ The idea was for us to discover how much we depend on foreign trade."

"Listen. Here's what I wrote: 'I woke up to the music on the clock radio. I jumped out of bed, took a shower, got dressed, and ate breakfast. After glancing at the newspaper's headlines, I left for school."

"What's so amazing about that?"

"Well, almost everything in my story came from another country. I even wrote it all down:

• "My clock radio was made in Japan, my slippers

came from Taiwan, and my robe is from India.

• "My comb was made in Mexico, my sweater in

Scotland, my shoes in Italy.

• "The hot chocolate I drank was made by a Swiss

company with cocoa beans from Ghana.

• "The newspaper I read is owned by an Australian

company, and it was printed on paper manufactured in Canada."

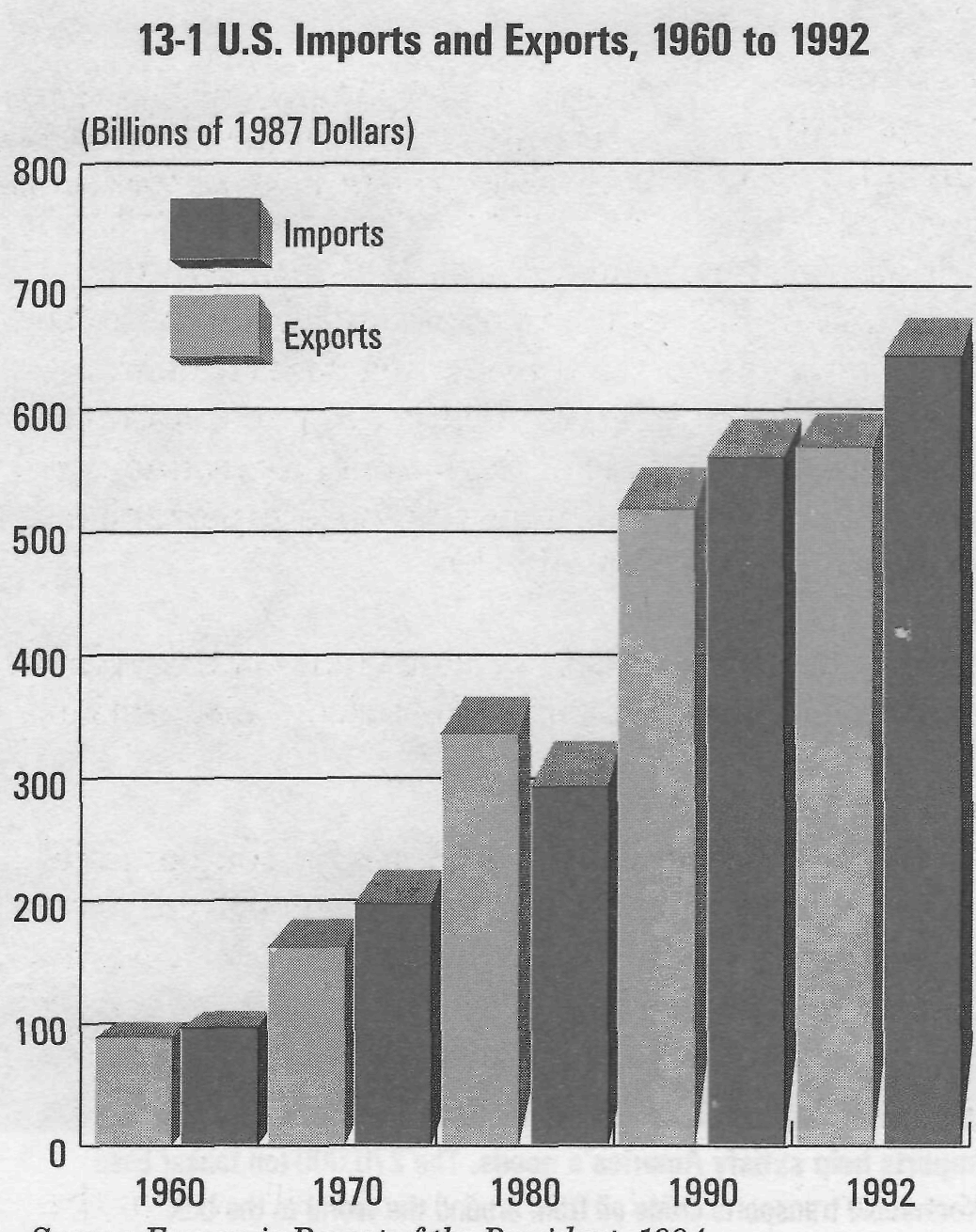

We all depend on goods and services from other countries. As Graph 13-1 shows, imports have risen steadily almost every year in the past 30 years. U.S. exports are about 10 percent of G.D.P.

13.1. The Benefits of Trade

Businesses in different countries trade with one another for the same reason individuals and business firms trade within a country - both sides expect to benefit. They benefit because trade enables them to exchange things they don't need (surplus goods and services) for the things they do need and want.

Absolute advantage. Some areas produce goods others cannot. For example, because of Florida's warm climate and soil, farmers there grow oranges but not wheat. Kansas farmers grow no oranges, but they do grow wheat. Since people in Florida and Kansas like to have both wheat and oranges, farmers in each state specialize in their crops and trade the surplus.

Kansas farmers could build special greenhouses for growing oranges, and Florida farmers might find a way to grow wheat, but the costs of doing so are probably very high. So by trading in their specialties, both areas benefit.

Manufacturing can also be performed more efficiently in some parts of a country than in others. Natural resources, an adequate labor supply, and transportation facilities have promoted the development of certain industries in particular regions of the country. For example, the computer industry is concentrated in Northern California, the steel industry in Western Pennsylvania, and large automobile factories in Southern Michigan.

What is true for regions of the United States is also true for the world. Nations have natural advantages because of differences in climate, natural resources, labor supply, capital, and technology. These differences make it sensible for them to specialize in the production of some products and to buy the other things they need from other countries.

Some countries, like Zaire and South Africa, are rich in certain mineral resources. Table 13-3 lists examples of minerals American businesses must purchase from abroad. Other countries, like Honduras and Guatemala, have a climate and soil that supports tropical crops. Still others, like Switzerland and Japan, have a high concentration of capital resources and a skilled labor force. In each of these instances, special conditions give one country an advantage over others in the production of certain goods or services.

When businesses in a nation can produce an item more efficiently than another, they are said to have an absolute advantage. Because of its climate and geography, Costa Rica can produce bananas far less expensively than it can produce computers. The United States, because of its technology, has the equipment and trained workers to produce computers. The United States has an absolute advantage in the production of computers; Costa Rica has an absolute advantage in growing bananas.

By specializing in those items for which they have an absolute advantage and trading their surpluses with

one another, Costa Rica and the United States will each wind up with more bananas and more computers than if they tried to produce both on their own.

Comparative Advantage. Not all nations have absolute advantages. Still, they engage in foreign trade because of the principle of comparative advantage. A nation has a comparative advantage in the production of a particular item when the opportunity costs of producing that item are lower than the opportunity costs of producing another.

This sounds complicated, but the following example should help you understand.

While she was in law school, Dorothy Dixon worked as a part-time hair stylist. Even today this highly successful trial lawyer could, if she wanted, cut hair as well as any professional. But Dorothy's three children have their hair styled at a local salon. She pays someone else to cut her children's hair because she can use the same time to earn much more money practicing law. In other words, her opportunity cost-what she would have to give up to cut her children's hair-is very high. It's to Dorothy's advantage to practice law and let someone else cut her children's hair.

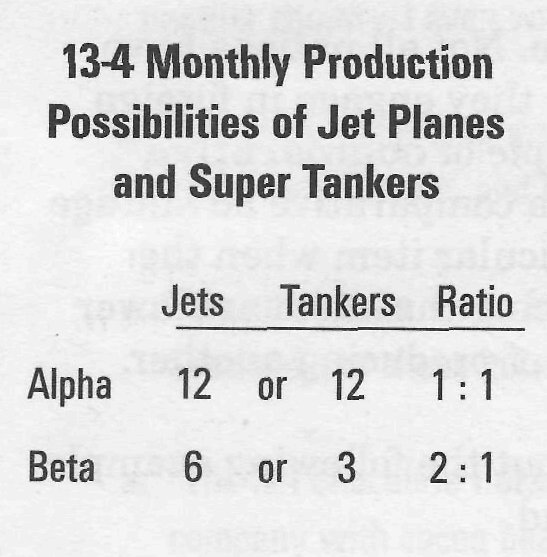

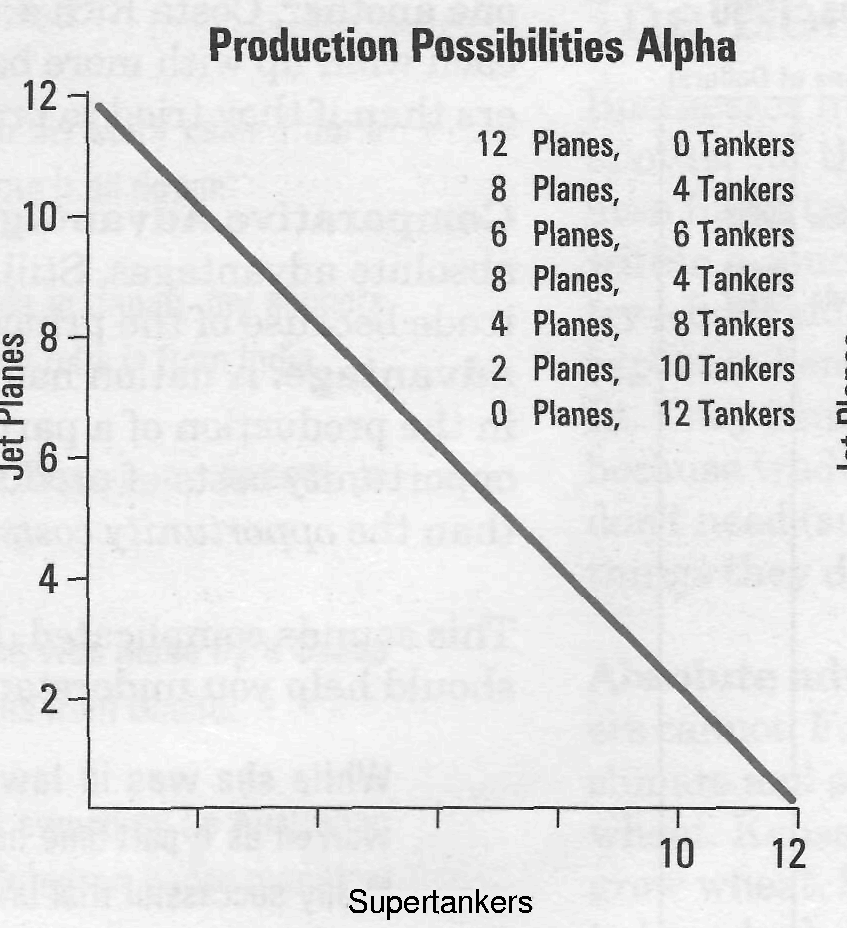

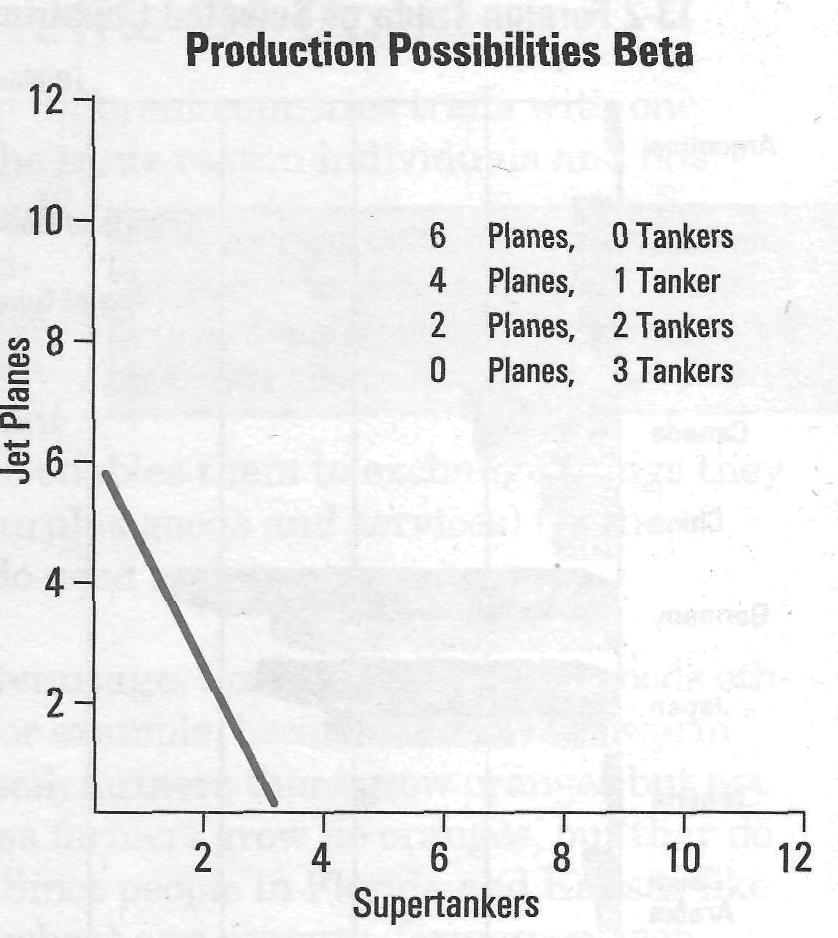

To illustrate comparative advantage working on an international scale, consider the case of the mythical nation of Alpha, which in one month could produce 12 jet airplanes or 12 ocean-going supertankers. Beta, another nation, is identical in population size to Alpha, but because of the state of its technology it can make only six jet planes or three supertankers in a month. (See Table 13-4.)

Clearly, Alpha is able to produce more of both planes and ships than Beta. But take a closer look at this situation.

As the production volume and production possibilities curves in Table 13-4 show, the opportunity cost for a single jet plane in Alpha is one tanker. So, if Alpha chose to produce both jets and tankers, it could turn out six of each in a month, or four of one and eight of the other, and so forth.

Beta, on the other hand, is twice as efficient in the production of jets as in the production of tankers. If Beta wanted to produce a tanker, it would have to give up two jets. Its production possibilities would also include four jet planes and one tanker, or two jets and two tankers.

Alpha is able to produce more planes and ships than Beta. Within its own economy, Beta is more efficient in the manufacture of planes because it can turn out two in the time that it takes it to produce one ship. Because of these differences in efficiency, if Alpha were to specialize in the production of ships while Beta produced only planes, the two nations could work out a trade that would benefit both. Here is why.

In Alpha the opportunity cost of a single plane is a single ship. In Beta a single ship costs two planes. Suppose the two nations worked out a deal in which Alpha traded two tankers for three Beta jets. Both nations would come out ahead. Alpha would save the cost of one ship by obtaining three jets for two of its tankers. Beta would save the cost of one plane by obtaining two tankers for three of its jets.

The law of comparative advantage explains why it pays nations to specialize in the production of those goods and services in which they have the greatest comparative advantage. When every country does what it can do best, all countries can benefit because more of every good or service can be produced without wasting labor, capital, and natural resources.

Unfortunately, the real global economy is more complex than the two-product, two-nation models found in most textbooks. Certainly, a nation as large as the United States cannot specialize in one product, or even a dozen; but it still must compete in a global market. And the global market, like any other competitive market, is constantly adjusting to consumer demands, changing technologies, and other forces that affect supply and demand.

The United States has the workers, technology, and natural resources to manufacture cars, airplanes, computers, televisions, and many other products. The U.S. automobile industry once dominated both the U.S. market and much of the world's. Today it is competing with car manufacturers from around the world for its share of the automobile market. Boeing has dominated the passenger airplane industry, but today it is facing growing competition from the European Airbus consortium. The production of televisions, on the other hand, has shifted from the U.S. almost entirely to Asian countries. When businesses in one country are threatened by competition from another, governments and politicians often put aside economic theory and create barriers to trade.