12.7. Monetary vs. Fiscal Policy

During the 1960s and 1970s, a debate raged between economists over the question, "Which is more effective in controlling the business cycle, monetary or fiscal policy?" Those favoring the monetary side of the argument were known as monetarists; those arguing the fiscal case described themselves as Keynesians (See "The History of Economic Thought" page 157).

Using a variety of statistical studies, monetarists attempted to show that past recessions and the Great Depression were the result of an imbalance in the money supply. They concluded that those hard times could have been avoided if only the Federal Reserve System had acted more wisely.

Keynesians disagreed with the monetarists' statistical methods and their conclusions. Fiscal policies, they claimed, in the form of appropriate changes in the level of government spending and taxation, were by far the most powerful economic tools for stabilizing the economy. This was seconded by President Nixon who, in the 1970s, asserted that "... we are all Keynesians."

More recently, economists have begun to agree that both fiscal and monetary policies can be used effectively to stimulate the growth of the economy or reduce the effects of inflation. In general, fiscal policies are more difficult to implement because of the time it takes for them to travel through the political process. However, once agreed upon, the impact of a new fiscal policy can be felt quite quickly.

Unfortunately, as indicated earlier, in the time required to develop a new tax law or spending strategy, economic conditions may change, and the new policy may be ineffective or even harmful.

Monetary policies, on the other hand, can be changed or adjusted quickly. The effects of higher or lower interest rates or changes in the money supply, however, are more subtle and often take longer to have an impact.

With fiscal and monetary policies, as in life, balance is probably important. Just as you must decide how much time to spend working an after-school j ob, studying, listening to music, or playing ball to achieve your personal goals, it is probably unwise to rely on either fiscal or monetary policy alone. Both can be useful.

Summary

Economic activity is measured by a variety of statistical measurements or economic indicators. One of these is the gross domestic product (GDP). It is the money value of the final goods produced in the country during the current year. When the GDP is adjusted for changes in the price level, it is called the "real GDP." The unemployment rate, which measures the number of people unable to find work, is another frequently cited indicator of economic health.

The business cycle is the pattern of periodic ups and downs of business activity. Economists often describe the cycle in terms of its four phases :peak, recession, trough, and expansion.

In its efforts to stabilize the economy and achieve the goals set forth in the Employment Act of 1946, the federal government relies on the tools of fiscal and monetary policy.

Fiscal policies seek to adjust total demand through the appropriate use of the government's powers to tax and to spend. Fiscal policy is in the hands of the president and Congress.

Monetary policies seek to achieve similar goals by regulating the money supply. Monetary policies are determined by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

In times of recession, fiscal policies call for some combination of tax reductions and increases in government spending. Monetary policies in those times seek to increase the money supply by increasing purchases of government securities by the Open Market Committee, lowering the discount rate, and reducing the reserve ratio.

In times of inflation fiscal and monetary policies follow an opposite course.

Reading for Enrichment

Measuring GDP: Expenditure vs. Income Method

Chapter 2 described how the Gross Domestic Product could be calculated by totaling the consumer, business, and government spending and net exports within a single year (C + I + G + X). In 1992 for example, the GDP of $6,038.5 billion consisted of the following expenditures:

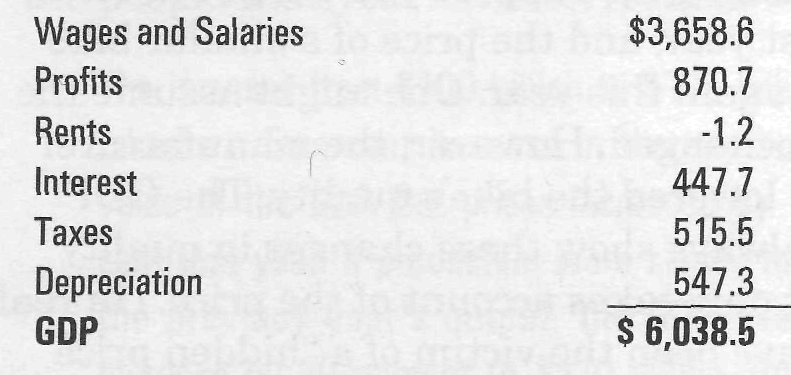

Totaling expenditures—the expenditure approach to GDP—is one method of calculating the GDP. But if you remember the "Circular Flow of Money, Goods, and Services," you will understand that the money spent by consumers, governments, and businesses became someone else's income. Consequently, you can also calculate GDP by adding different types of income-the income approach to GDP. Others receive the expenditures to purchase the GDP as wages, profits, rent, interest, taxes, and depreciation. (National income figures typically exclude depreciation; however, they are included in the income approach to GDP. Depreciation is the value of capital goods consumed during the production of the GDP.) In 1992 the $6,038.5 billion consisted of the following:

Explaining Economic Fluctuations:

Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand

Chapter 2 took an out-in-space look at the American economy. From that vantage point you compared the production of goods and services and the payments generated by the process to a series of circular flows. You noted that the flows are constantly expanding and contracting. During periods of recession the flows diminish, and during periods of expansion they grow. Most economists agree that these fluctuations are related to changes in aggregate supply and aggregate demand.

Aggregate supply refers to all the goods and services provided by the economy. Aggregate demand, on the other hand, is the total planned spending by consumers, businesses, and governments for the purchase of the aggregate supply. Under an ideal situation "total spending" would be exactly equal to the dollar value of the total value of the goods and services produced by the economy.

In other words, aggregate supply would equal aggregate demand. However, not everything produced by the economy is always sold in a year. When that happens economists say that business firms "purchase" the surplus they produce and add it to their inventories.

C onsider

this example: the softball-loving nation of Hittenrun produces three

products-pitching machines, balls, and bats. Government spends no

money at all in Hittenrun. Everything is purchased by either

consumers or business.

onsider

this example: the softball-loving nation of Hittenrun produces three

products-pitching machines, balls, and bats. Government spends no

money at all in Hittenrun. Everything is purchased by either

consumers or business.

Now suppose aggregate demand was $12,000 less than aggregate supply. In order to sell their surplus merchandise, the following year Hittenrun's business firms will need to reduce their output, lower their prices, or do a little of both. Whatever they do, it will reduce the volume of money, goods, and services flowing through the economy.

But what if the opposite had occurred? If aggregate demand had been greater than the aggregate supply, Hittenrun could increase its output, raise its prices, or do a little of each. Whatever it chose, it would increase the volume of the circular flows.

When aggregate demand is less than aggregate supply, economists describe the difference as a deflationary gap. When aggregate demand is greater than supply, the difference is called an inflationary gap. By understanding how changes in the level of aggregate demand and aggregate supply can create these "gaps," governments can attempt to use fiscal and monetary policies to stimulate or reduce business activity to control the harmful effects of fluctuations in the business cycle.

The Automatic Stabilizers

The fiscal policies we have described so far are discretionary - they are applied when the policy makers decide to use them. One of the principal drawbacks of discretionary fiscal policies is that unless they are properly timed, they may arrive too late to do any good. This is not true, however, of the fiscal tools called automatic stabilizers.

Automatic stabilizers are "automatic" because they go into effect when needed, without action by the president, Congress, or their representatives. They are "stabilizers" because during recessions they increase government spending, reduce taxes, or some combination of the two. And in times of expansion, when personal income and prices are rising, the automatic stabilizers follow an opposite course; they reduce government spending and increase taxes.

One such automatic stabilizer is the personal income tax. During times of recession, people earn

less and are, therefore, taxed at a lower rate. In this way the personal income tax provides the public with exactly what is called for during recessions tax cut. In boom times inflation pushes wages and salaries to higher and higher levels. As this happens people are pushed into higher tax brackets. Once again, tax policy automatically keeps with fiscal goals by increasing taxes during inflationary times.

Another set of automatic stabilizers increases and reduces government spending, when needed, to combat recession or inflation. These are the nation's unemployment and welfare benefits. In times of recession government spending automatically increases as the number of those eligible to receive unemployment insurance and welfare benefits increases. When the economy improves, unemployment declines, and government spending for these programs is automatically reduced.

During periods of prosperity and high employment, taxes automatically rise, putting money into the unemployment insurance fund. This helps to reduce spending at a time when inflation is a threat and makes funds available when a recession appears.

Wesley Clair Mitchell (1874-1948) Pioneer in the Scientific Study of Economics

Wesley Clair Mitchell is remembered because he worked to make economics as precise as the physical sciences. This was hard, for unlike chemistry and physics whose natural laws help predict events with some certainty, economics is a social science subject to the whims of individual and group behavior.

At the heart of Mitchell's work lay his effort to gather statistical data to describe and explain economic events. While statistics are an everyday tool for today's economists, they were not before World War I when Mitchell began. His challenge was to suggest what data ought to be gathered, then describe how it might be used to study the economy.

Mitchell's theories were published in 1913 in Business Cycles, a landmark book in the history of economic thought because of its use of statistics and statistical models as economic tools. The book suggests that in free enterprise systems, like the United States, the ups and downs of certain kinds of economic activities reflect trends in the economy as a whole. In other words, Mitchell explained that by studying fluctuations in things like profits, investment, and employment, economists could understand and predict changes in economic activity more accurately.

In 1920 he and other economists created the National Bureau of Economic Research with Mitchell as its director. Under his leadership, the organization pioneered in the study of national income and the business cycle. Their methods of collecting and using statistical data set a standard by which economic research is still measured.

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) Theorist Who Brought Economics Into the 20th Century

John Maynard Keynes (rhymes with "brains") stands with Adam Smith and Karl Marx as one of history's most influential economists. The son of a British economist, Keynes earned a fortune through trading stocks and commodities. He served the British government as a financial adviser and treasury official, and he was a key participant in the negotiations following both World Wars I and II.

Although Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations in 1776, mainstream economists' thinking had changed little by the 1930s. Most agreed with Smith: that the best thing government could do to help the economy was to keep its hands off. They reasoned that as long as the economy operated without interference, the forces of supply and demand would balance. Then, with total supply and demand in equilibrium, everyone looking for work could find a job at the prevailing wage, and every firm could sell its products at the market price. But the 1930s introduced the Great Depression. Despite the assurances of classical economists, the fact was that unemployment and business failure had reached record proportions in the United States and the rest of the industrialized world. It was at this time (1936) that Keynes' General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money was published. His book transformed economic thinking in the 20th century, much the way that The Wealth of Nations had in the 18th. Keynes demonstrated that it was possible for total supply and demand to be at equilibrium at a point well under full employment. What is more, Keynes demonstrated that unemployment could persist indefinitely, unless someone stepped in to increase total demand. The "someone" Keynes had in mind was government. He reasoned that if government spent money on public works, the income received by formerly idle workers would lead to increased demand, a resurgence of business activity, and the restoration of full employment. The suggestion that government abandon laissez faire in favor of an active role in economic stabilization was regarded as revolutionary in the1930s. Since then the ideas advanced by the "Keynesian Revolution" have become part of conventional wisdom. Now, whenever a nation appears to be entering into a period of recession or inflation, economists and others who support Keynes' ideas-"Keysesians" -immediately think of steps the government might take to reverse the trend.