Chapter 12 economic stability

Have you ever trudged from place to place looking for a job, only to be told that jobs just aren't available - even though you have the right skills? Or is there a "Help Wanted" sign in half the stores in town?

Have you noticed that CDs, movies, and pizza cost more than they did a few months ago?

Do you hear people muttering about the ups and downs in the stock market?

Does it seem like a good time to buy a car? Are interest rates going up or down? How about the cost of insurance and gasoline?

The answers to these questions provide you with personal economic indicators. They help you determine if times are good, or if people are having difficulty earning a living and making ends meet. Economists, business managers, and government officials study unemployment rates, price indexes, stock market trends, interest rates, and many other statistics to measure economic activity. They rely on these indicators to tell them where the economy has been and where it seems to be heading. Although they know that economics is not a precise science, the indicators enable them to make better decisions and more accurate predictions about the future.

12.1. Measuring Economic Activity

One of the most commonly discussed and useful economic indicators is the gross domestic product (GDP).

The Gross Domestic Product. For many years, gross national product (GNP) was used to measure the total dollar value of all the goods and services the economy produced in a single year. In other words, GNP revealed much about the nation's economic health. If the GNP increased, there was more of everything available for Americans. If the GNP decreased, less was available.

In 1991, however, the U.S. government began measuring the economy's production with gross domestic product (GDP), because it provides a more accurate measure than GNP of production within U.S. borders. Also, since most of the world's countries use GDP, international comparisons using GDP are easier to make.

The major difference between GNP and GDP is in the way each counts goods and services produced in other countries by U.S.-owned firms. GDP only includes production within our borders. GDP does not include goods and services produced overseas, even if the resources used are owned by U.S. citizens or firms. So, a Hewlett-Packard calculator assembled in Mexico is not counted as part of GDP. On the other hand, a Honda produced in Ohio is part of GDP. (GNP would have included the Hewlett-Packard calculator, but not the Honda)

Since GDP is such an important statistic, the government agencies that gather data for their reports take great care to see that they are accurate. Nevertheless, GDP statistics can be misleading if they are not used properly. Here are some ideas to keep in mind when using GDP data.

• GDP includes only final goods. GDP is the total value of the goods and services produced by the economy in a single year. But this is not as simple as it sounds. To avoid overstating the GDP by counting the same item two or more times, only final goods are included. Let's suppose that a bicycle manufacturer pays $300 for the parts and labor used in making a mountain bike. The manufacturer sells the bike to a bicycle shop store for $400. The store sells the bike for $750. How much did the production of a single mountain bike add to the GDP? Since only final goods are counted, $750. The $300 paid to the parts suppliers and the $400 paid to the manufacturer were not added to the final count because the $750 already included them.

• Used goods are not included in the GDP. Two years later, the bike was sold for $250. How much was added to the GDP? Zero. Since used goods add nothing to the nation's wealth, only new goods are counted.

• «Net exports" are included in GDP. This means that GDP increases when more goods and services are exported than are imported from other countries. GDP declines when more goods and services are imported than are exported. In recent years, imports have exceeded exports and the difference between exports and imports has been subtracted from GDP.

• Inflation can distort the significance of growth in the GDP. When prices are rising, as they do during periods of inflation, GDP may increase even though the production of goods is unchanged. This is because GDP is measured in terms of current prices.

Suppose GDP increased from $100 billion to $105 billion one year. That same year the inflation rate was 10 percent. Based on this data, would you say that more goods and services were available for the people that year? The correct answer is "no":

The increase from $100 billion to $105 billion represents a 5-percent increase in the current dollar value of the GDP. But prices increased by TO percent that year. If production were simply to match the previous year's output, the GDP needed to increase by 10 percent to $110 billion. But since the new GDP was only $105 billion, the total output (or real GDP) actually declined.

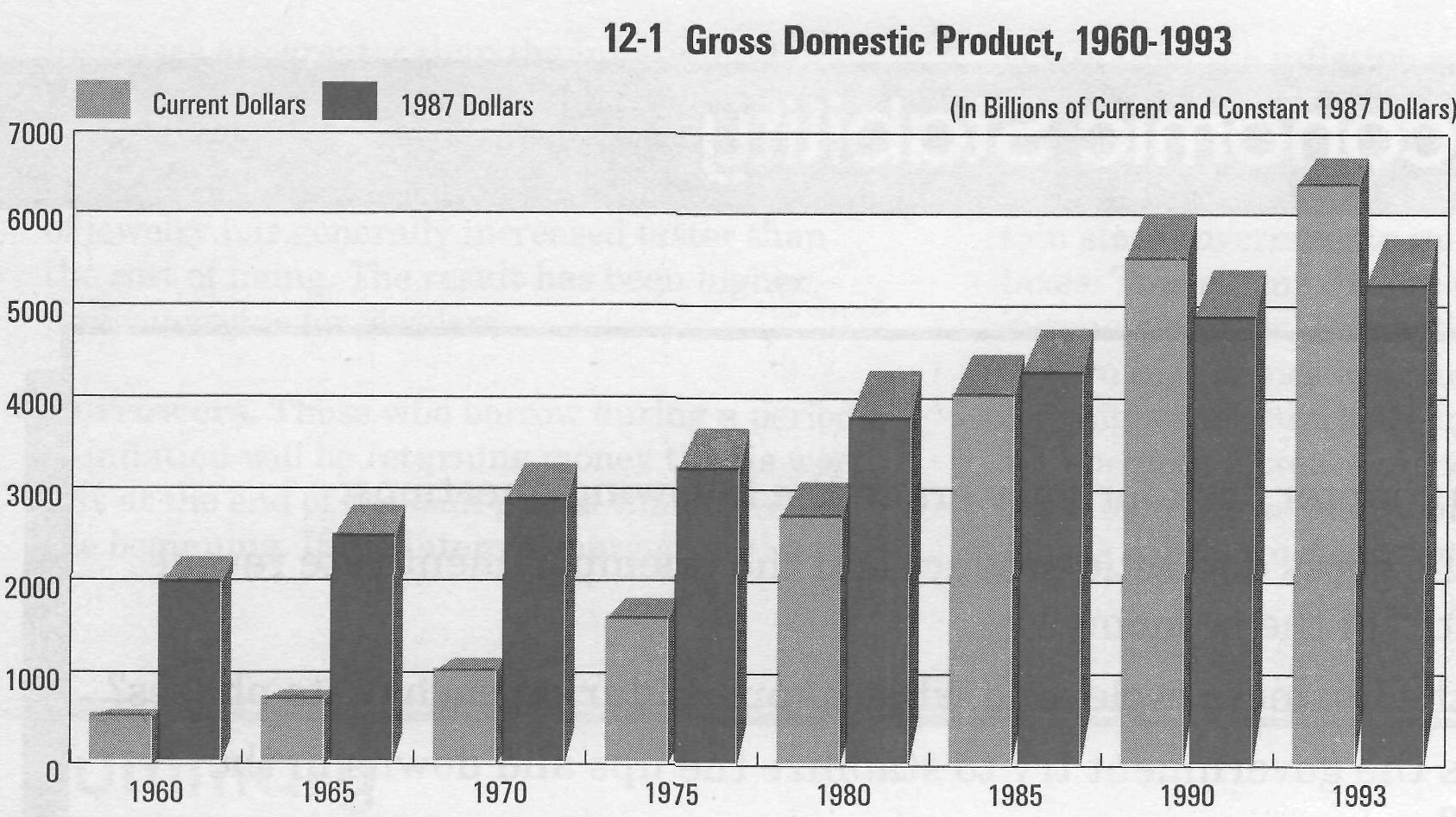

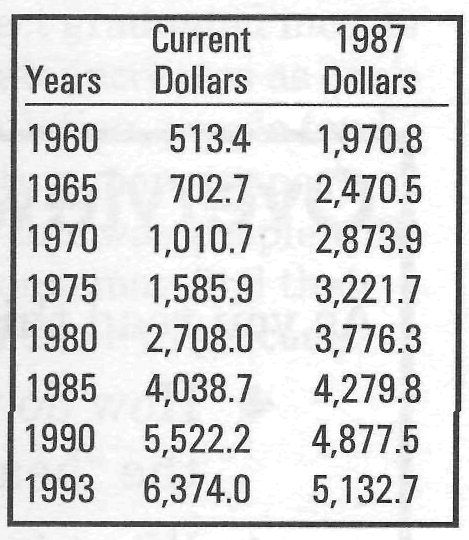

To avoid these problems, economists can adjust the GDP for changes in the price level (see Figure 12-1). When this adjustment is made, the result is called the real GDP or the GDP expressed in constant dollars. Constant dollars are similar to an index number because they reflect changes in the purchasing power of the dollar from a base year. Economists refer to GDP in constant, rather than current, dollars when comparing the nation's gross domestic product between years.

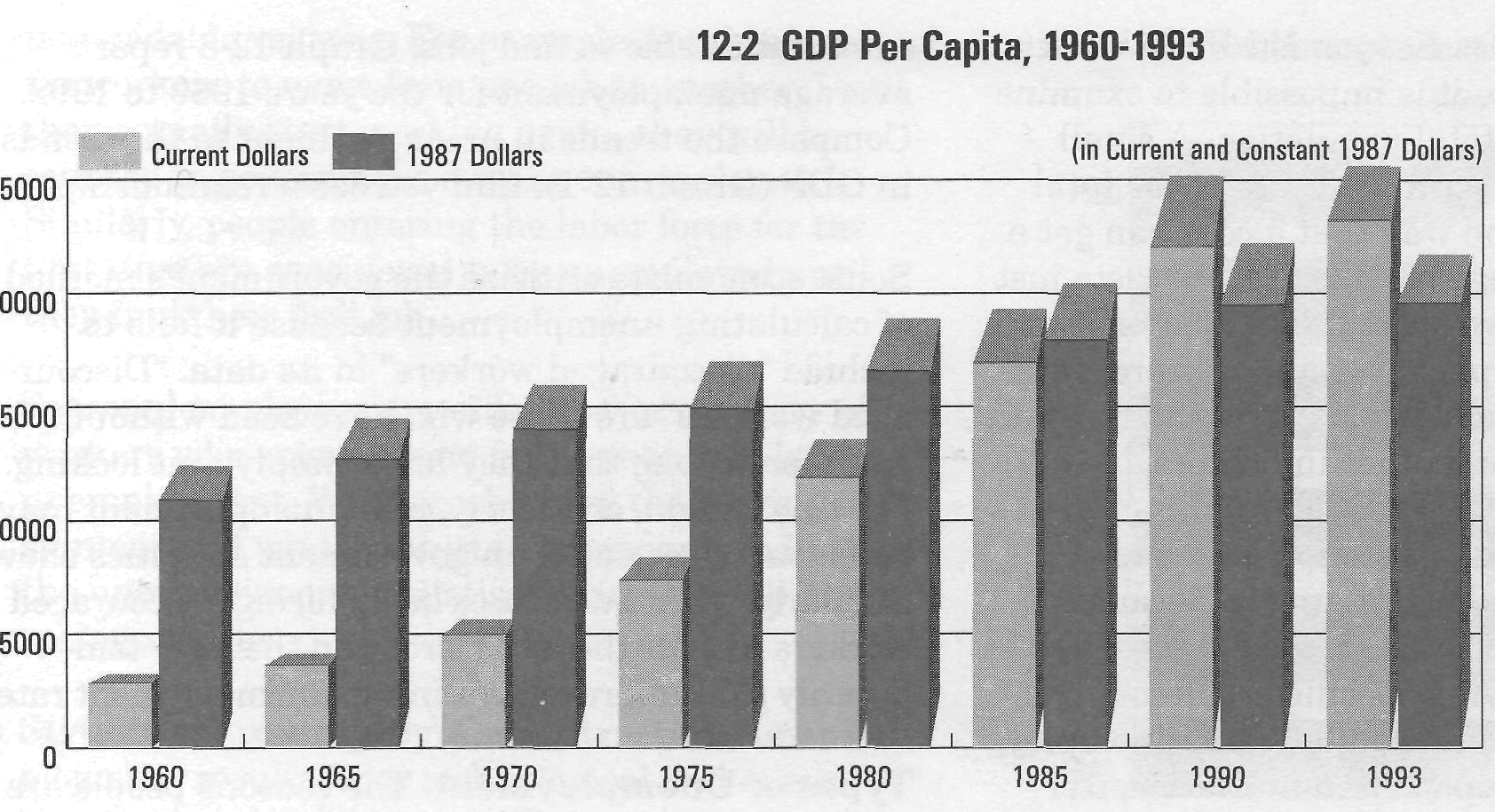

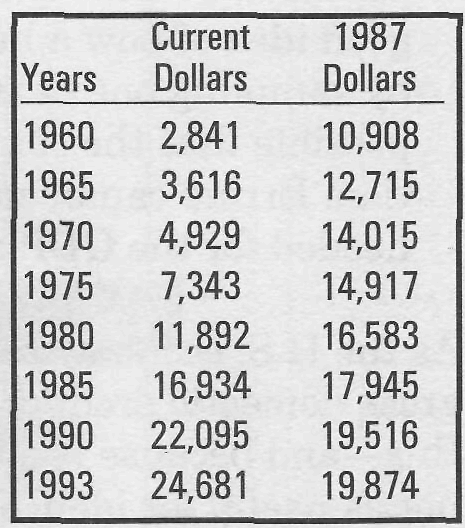

• Population changes. The GDP is like a huge pie that contains everything produced in a year. But everyone shares that pie. If the GDP rose by 5 percent, but population rose by 10 percent, everyone would get a smaller piece of the pie (assuming equal shares), because the growth in population was greater than the growth in output of goods and services. Economists adjust for this by dividing the GDP by the size of the population to get GDP per capita (see Figure 12-2).

• Quality changes. Suppose you paid $500 for a bicycle last year, and the price of a similar bike was $500 again this year. One might assume the price is unchanged. However, the manufacturer may have lowered the bike's quality. The GDP does not always show these changes in quality because it only takes account of the price. (In reality, you have been the victim of a "hidden price increase." Can you explain why?)

The opposite can also be true, especially in high technology. A computer you buy for $2,000 may have more power and be of higher quality than a computer you could have purchased last year for $2,500.

• Harmful goods and services. Don't assume that the GDP is a measure of the nation's well-being. Some of the goods and services included are useless or harmful. For example, cigarettes probably cause lung cancer and other serious ailments, but they are added to the GDP along with food, medicine, and other beneficial items. Also, in producing GDP, Americans create air, water, and solid waste pollution. The costs of these harmful externalities (see Chapter 2) are not subtracted from GDP.

• Nonmarket production. Suppose you earn extra money by baking cakes. You bake 10 cakes, sell nine, and eat one. GDP will include only the cakes you sold. If you mow someone's lawn and receive payment for it, your payment is included in the GDP and your service is recognized as being part of total U.S. output. If you mow your own lawn, however, your work is not recognized by the GDP figures.

Goods and services illegally produced and sold are also omitted from GDP figures. For example, the millions of dollars spent on illegal drugs are not counted as a part of GDP.

• Measurement errors. Economists often work with samples, because it is impossible to examine every member of the total population. A small sample can give an accurate picture of the total population in the same way that a cook can get a good idea of how a huge pot of soup will taste just by sampling one or two spoonfuls. But it is always possible that the sample is not a true representation. Errors can be made when gathering the data needed for the GDP and other indicators.

As the U.S. economy and population have grown, gross domestic product also has grown. Because of this-and because the U.S. GDP is so large-GDP is not as useful for identifying specific problem areas in the economy as some other indicators. Unemployment statistics, for example, often indicate better how well Americans are using their resources.