- •Chapter 11 money & financial institutions

- •11.1. Money

- •11.2. Money Today

- •11.3. The Development of Banking

- •11.4. Banking Today

- •11.5. How the Banking System "Creates" Money

- •11.6. The Federal Reserve System

- •11.7. The Value of Money Can Change

- •11.8. What are the Causes of Inflation?

- •11.9. Who Suffers or Benefits from Inflation?

11.9. Who Suffers or Benefits from Inflation?

Inflation affects people differently: some suffer, while others benefit.

Those most likely to suffer from inflation are

people living on relatively fixed incomes, savers, lenders and business.

• People living on relatively fixed incomes.

During periods of inflation the cost of living increases. Therefore, it is necessary to earn more just to maintain your present living standard. How much of an increase is necessary? At least as much as the rate of inflation - the increase in the cost of living. In other words, if the cost of living increased by 10 percent in 1991, a person with a $20,000-a-year income in 1990 would have to earn $22,000 ($20,000 + 10 percent) in 1991 just to stay even. Certain groups, such as those living on fixed retirement pensions, cannot increase their incomes enough to offset the effects of inflation. When this happens, their standard of living will decline. To protect people on fixed incomes, Social Security benefits are adjusted for inflation.

• Savers. Some people put their money into savings accounts or bonds that guarantee a fixed rate of return (usually called "interest"). Unless the rate of return is at least as high as the inflation rate, the money returned to a saver will purchase less than the sum he or she set aside.

• Lenders. Those who lend money are in the same position as those who save. If inflation increases during the term of a loan, then the money paid when the loan comes due will be worth less than the original loan, unless the interest rate on the loan was greater than the inflation rate.

• Business. Business is hurt by inflation because it causes uncertainty and makes it hard for managers to predict future costs. It also raises production costs.

Those who benefit from inflation are those who can easily increase their incomes, borrowers, and government can benefit from inflation. Here are some reasons why.

• Those who can increase their incomes.

Certain professions, industries, and labor groups find it easier to increase prices and wages during periods of inflation than at other times. If the increases are greater than the inflation rate, those people will be better off than before the run-up in prices. A case in point is the retail jewelry trade. During periods of inflation, the price of jewelry has generally increased faster than the cost of living. The result has been higher profit margins for jewelers.

• Borrowers. Those who borrow during a period of inflation will be returning money that is worth less at the end of the loan period than it was at the beginning. If the interest charged on the loan is less than the inflation rate, those who borrowed will benefit from the difference.

• Government. The federal government and certain state governments collect graduated income taxes. This means the tax rate increases as one's income increases. During inflation, people tend to earn higher incomes, putting more taxpayers into higher tax brackets. In this way people with a 10-percent increase in income may find their taxes increase an additional 12 or 15 percent. This is called bracket creep.

Summary

Money can be anything that is generally accepted in payment for goods or services. It provides a medium of exchange, a measure of value, and a store of value. Principal forms of money are currency, demand deposits (checking accounts), and other checkable deposits.

Financial institutions such as commercial banks, savings and loan associations, and savings banks are essential to the smooth operation of the U.S. economic system because demand deposits and other checkable deposits held by banks and thrifts make up the largest part of the money supply. These institutions also provide a safe place for the deposit of funds and to serve as a source of loans and other financial services.

Because loans are typically added to demand deposits, one can say that the lending ability of the banks serves to "create money." How much money the commercial banks can create is limited by the reserve ratio, which directly affects the amount of money that a bank can lend at any particular point in time.

The Federal Reserve System is the nation's central bank. It provides banking services for financial institutions and supervises their activities. It also acts as a bank for the federal government.

The "value of money" is really its purchasing power-the amount of goods and services it can buy. The purchasing power of money can increase, as it would during periods of deflation, and it can decrease, as it does during periods of inflation.

The causes of inflation are generally described as either demand-pull or cost-push. Demand-pull inflation is caused by an excess of purchasing power that serves to drive up prices ("too much money chasing too few goods"). Cost-push inflation is brought about by rising production costs that feed upon one another. Although certain groups within the economy may benefit from the increasing prices associated with inflation, more individuals and the economy as a whole are likely to suffer.

Reading for Enrichment

How Much Money Is In Circulation?

That depends on how you count it.

Money, as defined here, is anything generally accepted in payment for goods and services. Clearly, then, your bankbook is not money; you could not walk up to a box office and buy a ticket to the movies with it. But you could withdraw money from the bank that same day, then buy your ticket.

Economists describe assets that are easily turned into cash as "near monies." Economists use the labels Ml, M2, M3, and L to refer to different categories of money.

Ml consists of the components listed in Table 11-1: currency, demand deposits, other checkable deposits, and travelers' checks.

M2 consists of Ml plus money-market

a ccounts,

savings accounts, money-market mutual fund accounts, and other

easily liquidated (converted to cash) kinds of savings.

ccounts,

savings accounts, money-market mutual fund accounts, and other

easily liquidated (converted to cash) kinds of savings.

M3 consists of M2 plus large-denomination certificates of deposit

($100,000 and above) held by private institutions.

L consists of M3 plus most securities that are within 18 months of

maturity (such as U.S. savings bonds, treasury bills, and other gov

Ernment-issued credit instruments). L, which stands for "liquidity" or

the

overall ability to spend, is the broadest definition of the money supply.

The Financial Crisis of the 1980s

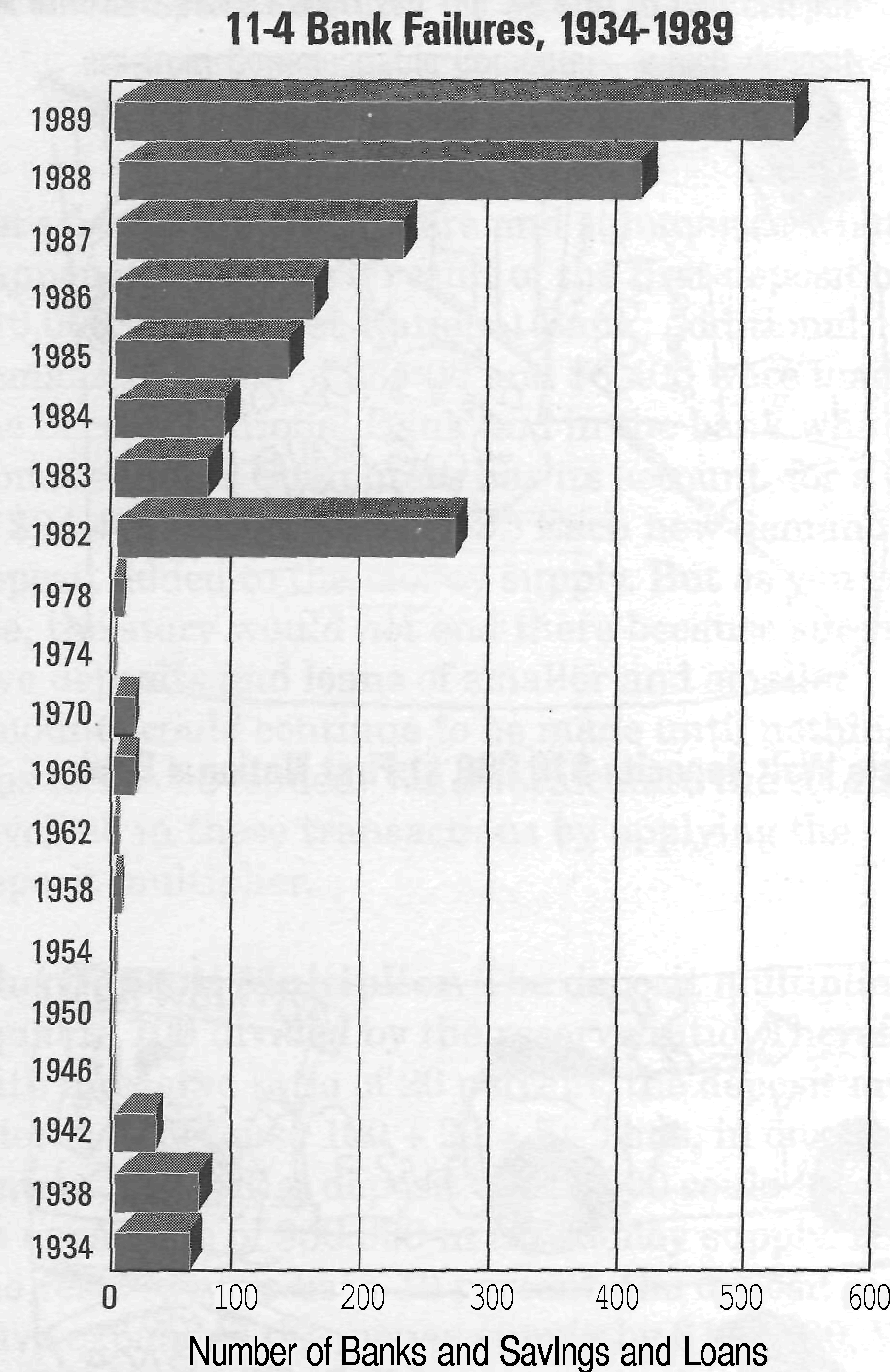

The graph to the right is a picture of failure-banking failure. The graph

shows that while banking failures were numerous in the 1930s and the

1980s, they were rare during the 35 years between.

The banking crisis of the 1930s caused great hardships for many depositors. In those days bank failure usually meant that a depositor's savings were wiped out. Consequently, rumors of financial trouble often led to a "run on the bank." Depositors would descend on the bank to demand their savings. The sudden demand was often a self-fulfilling prophecy as even healthy banks were brought to their knees by the sudden and unexpected large demands for cash.

To protect banks against runs and to restore public confidence in the banking system, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was created in 1933. The FDIC insured savings accounts in commercial banks and some savings banks against losses up to $2,500. Later, the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation was created and coverage expanded, so that now virtually all bank and thrift deposits are guaranteed up to $100,000.

Federal deposit insurance has done all that was expected of it. Bank customers no longer fear for the safety of their deposits. But, as demonstrated by the graph, deposit insurance has not eliminated bank failures. The rate of failure, particularly among savings and loan associations in the Western and Southwestern states, reached catastrophic proportions in the 1980s. Ironically, many experts now point to deposit insurance as one of the principal causes of the disaster.

As they see it, the confidence created by deposit insurance made so much money available that banks and thrifts were encouraged to make risky loans. As one critic put it: "A system in which all losses are guaranteed by the government, while all profits go to the owners, invites corruption and dishonesty." When the economy slowed, many borrowers were unable to repay their loans, and the banks and thrifts, unable to repay their depositors, were forced into bankruptcy.

The hardest hit deposit insurance agency was the FSLIC. By 1989 it was out of funds. Meantime, estimates showed that it would take another $100 billion to repay depositors in the bankrupt savings and loans.

The deposit insurance disaster led to the enactment of the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989. The legislation provided the funds needed to guarantee the deposits in the insolvent (bankrupt) banks and thrifts. It also eliminated many of the sloppy banking practices that caused the crisis. Although President Bush praised the new law, billions of tax dollars were needed to meet its objectives. Meanwhile (to the sorrow of those who view insurance as the source of the banking problem), the public remained confident that their savings would continue to be guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

Although the crisis is not over, bank failures have slowed in the 1990s. In 1990, 482 banks and thrifts closed, and just 181 in 1991.

Where Does Paper Money And Coin Come From?

Nearly all of the nation's currency is in the form of coins or Federal Reserve notes. Coins make up about 9 percent. They are produced by the U.S. Mint in Denver. Federal Reserve notes that range in value from $1 to $100 are printed by the Treasury's Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington, D.C. Bills of larger denominations are no longer issued.

The only other form of paper currency are U.S. Treasury notes which are issued in $100 denominations. Unlike Federal Reserve notes, which bear a green seal on the right side of the face of the bills, these carry a red seal. U.S. Treasury notes account for 1 percent of all paper currency.

But how does currency find its way from the printing presses and the mints into your pocket?

The 12 Federal Reserve banks order currency and coins from the Treasury, just as a supermarket orders different breakfast cereals to meet customers' needs. If your neighborhood bank doesn't have enough cash on hand, or is short of certain denominations, it orders what it needs from its account at the Reserve bank.

Hyperinflation In Argentina

They changed the menu every day at the Estrella de Oro restaurant in downtown Buenos Aires. But not for the reason you may be thinking: the dishes were usually the same. The reason the menu had to be changed was to allow management to raise the prices. You see, Argentina was experiencing hyperinflation. The value of its currency was falling at an astonishingly rapid rate.

How rapid? In January 1989, 17 australes (the austral is the Argentine unit of currency) were equal to one U.S. dollar. By May it took 175 australes to buy $ 1, and by September the austral had fallen to 615 to $1! Or, to put it another way, a bottle of soda that sold for 7 australes in January sold for 253 australes in September!

Inflation such as the kind that struck Argentina destroys the lives of many people. Those who set money aside for a college education, retirement, etc. find that their savings are all but worthless.

With prices rising daily, the incentive to save is replaced with the urge to spend. Paychecks are cashed immediately and converted to dishwashers, TVs, and refrigerators. Since no one will give credit in the midst of runaway inflation, consumers must pay cash for all their purchases.

When Americans read about the Argentine inflation, one of the first questions that comes to mind is, "Can it happen here?" Fortunately, for reasons that will be explained in the next chapter, we may answer with a confident "probably not."

The History of Economic Thought

Irving Fisher (1867-1947): Pioneer In Monetary Theory

Irving Fisher was a professor of economics at Yale University. An accomplished mathematician, he used his skills to explain many of his theories. In his best-known formulation, the equation of exchange, Professor Fisher showed the relationship between the quantity of money in circulation and the level of prices.

The equation of exchange is stated as follows: MV = PQ, where:

M = money supply

V = velocity of circulation

P = average price of goods and services

Q = quantity of units sold

Simply stated, the equation of exchange shows that total spending is equal to the total value of the goods and services produced by the economy. Here's why. M is the total amount of money in circulation, and V is its velocity. Velocity is simply the number of times that money turns over in a year. In other words, the amount of money in circulation, multiplied by the number of times it is spent (MV), is equal to the total amount of money spent by the economy in a year.

To illustrate, suppose that each student in your class produced a product to sell for $1. Your teacher buys the product from the student sitting in the first row, first seat. That student uses the dollar to buy the product from the student in the second seat.

The process continues around the room as each student uses the dollar from the preceding student to buy the product of the next student. Assuming that there are 30 in the class (including the teacher), 30 items will be sold. One dollar bill will be exchanged 30 times. Applying the equation of exchange, the total amount of money in circulation will be $30 because:

M = $1; V = 30; and MV = $1 x 30 = $30.

The equation of exchange helps to explain why prices (and therefore the value of money) fluctuate. Since MV = PQ, it follows that when V and Q are constant, any change in the money supply will directly affect prices. In other words, when the money supply increases, so will prices, and vice versa. We can also see that increases in the money supply will not result in price increases if the output of goods and services is increased at the same or a faster rate.