- •15.1. Urban Problems

- •15.2. What Can Be Done?

- •15.3. Poverty in America

- •15.4. Who are the Poor?

- •15.5. The Health-Care Crisis: An Overview

- •15.6. How Can America's Health-Care System Be Improved?

- •15.7. Farmers and their Problems

- •15.8. Economic Sources of the Farm Problem

- •15.9. The Global Connection

- •15.10. Federal Farm Aid

- •15.11. The 1990s and Beyond

- •15.12. Economic Growth and the Environment

- •15.13. Protecting the Environment

- •15.14. Air Pollution

- •15.15. Water Pollution

- •15.16. Land Pollution

- •15.17. The Economic Results of Regulation

- •15.18. The Twin Deficits

15.7. Farmers and their Problems

In 1985 about 400,000 farmers went into bankruptcy or quit farming because of financial troubles. This happened despite the fact that American farmers are the most efficient in the world, and despite the more than $20 billion spent that year by the federal government to assist them.

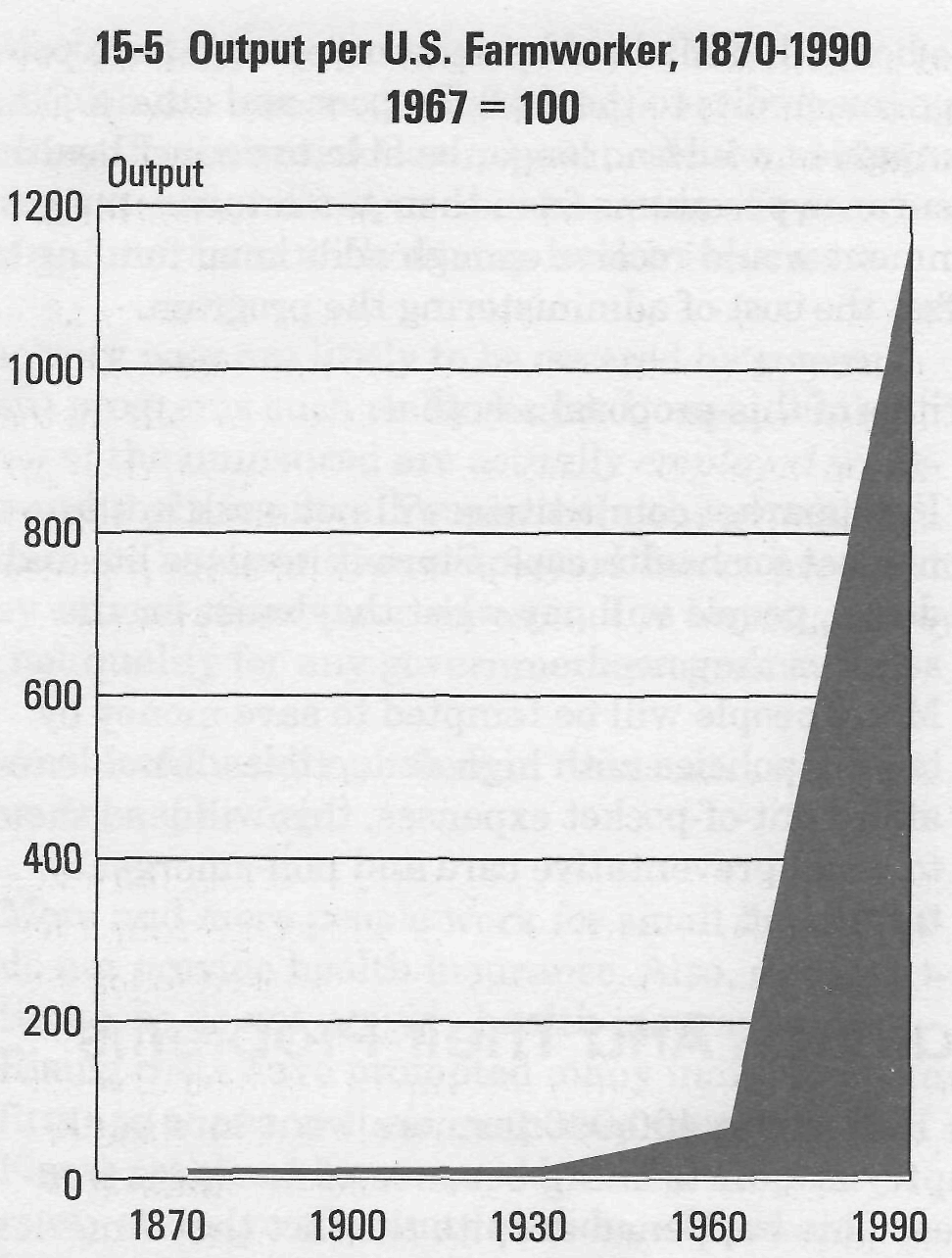

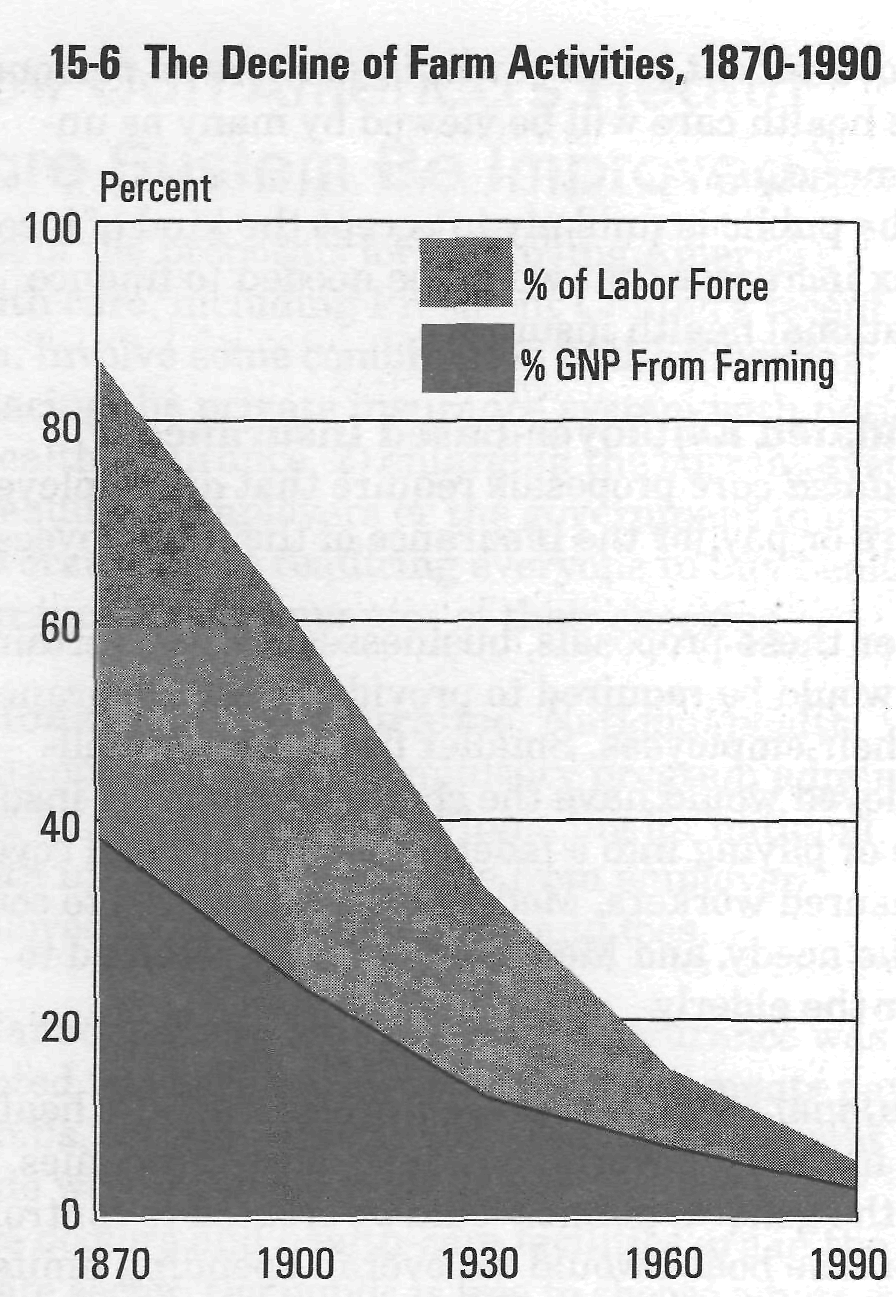

There is nothing new about these problems. Farmers have been leaving the land ever since the end of the World War I. In 1920 about 31 million Americans lived on 6.5 million farms. By 1990 this had shrunk to 4.5 million living on 2 million farms. Despite the shrinkage in the number of farms and farmers, however, the total output of the nation's farms increased! (See Graphs 15-5 and 15-6).

15.8. Economic Sources of the Farm Problem

With the number of farmers decreasing, their output constantly increasing, and federal aid to farmers reaching all-time highs, one might wonder why farmers have been having such difficulty.

• What are the causes of the farm problem?

• How has the global economy affected farmers?

• What has the government done to help farmers?

• Why is government aid to farmers a controversial issue?

Farmers Sell in Competitive Markets But Buy in Administered Markets. Much American industry is concentrated in the hands of a few large producers. Aircraft, motor vehicles, and farm machinery, for example, are produced by only a few industrial giants. There are so few producers that it is possible for supply and prices in those industries to be controlled and stabilized.

By contrast, farmers, numbering in the millions, work in conditions of nearly perfect competition. As a result, they are unable to control supply or prices. When crop yields are high, farm prices are bound to fall. So the prices farmers receive decline while the prices they pay for their needs go up, remain steady, or drop very little.

Farmers Have Difficulty Controlling Production. Many factors place farmers at a disadvantage, compared with industry, in planning and controlling output. Suppose, for example, that the demand for cotton clothing drops. Textile manufacturers can lay off workers, shut down plants, or shift to the manufacture of cloth made of artificial fiber. In this way the supply of cotton cloth will be reduced and its price maintained. For cotton farmers, however, it is a quite different story. With thousands of farmers scattered throughout 10 states, it would be impossible for them to agree to limit production.

Farmers are at the mercy of nature. Once the crop has been planted, there is not much they can do except harvest it when it matures, and take whatever price they can get for it. Weather also poses problems. Sun and rain may have little or nothing to do with the operations of a manufacturing establishment, but they can mean life or death to farmers.

Farmers' Costs Are Mostly Fixed. In many industries variable costs are a large percentage of the total. Such costs can be eliminated when things are slow. Factory output can be reduced and workers laid off to cut operating expenses. For the farmer, however, it is not unusual to find that nearly all costs are fixed, at least in the short run. Most farm labor is supplied by farmers and their families, so they can save little by laying off workers. Nor can they lay off their cows, hogs, or sheep.

The Demand For Farm Products Is Relatively Inelastic. The demand for farm products does not change as readily as the demand for many other types of products. Your need for food changes little, whatever your income. If your income doubles, you may buy better or more expensive food, and perhaps you will eat a little more, but you will not double your total intake. The reverse is also true. If farm prices should fall, the inelasticity of demand would result in less-than-comparable increases in the demand for farm products. This means that farmers do not share in our increasing national prosperity to the same extent as producers of other goods. In fact, per capita food consumption in America today is about the same as it was in 1925 (about three-fourths of a ton annually).

Farmers Often Must Borrow. Few farmers have enough money of their own to buy a farm; purchase equipment, seeds, and fertilizer; hire farmhands; and plant a crop. Farmers typically borrow for these things, hoping to pay off the mortgage on the farm in two or more decades and repay the loan for seeds and fertilizer when the crop is harvested and sold.

Crop failure, for whatever reason, can be a source of ruin because those who lend money expect to be repaid, regardless of the size of the farmer's crop. In addition, bumper crops can bring on unexpectedly low prices, once again making it difficult for farmers to repay their loans.

When prices are high and demand is strong, the farmer may decide to go into debt still further-duy more land, construct new buildings, and purchase more machinery. Then, if prices should fall, the burden of debt becomes heavier still as new loans must be repaid in addition to old ones.

This is exactly what happened to many Midwestern farmers in the late 1970s. A worldwide grain shortage induced many farmers to borrow in order to expand their productive capacity. Then, in the mid-1980s, the shortage disappeared and grain prices fell. Unable to meet their mortgage payments, thousands of farmers were forced into bankruptcy and out of farming.

Events in rural Iowa have been typical. In 1980 the average Iowa farm was valued at $523,000. By 1985 this had shrunk by nearly $200,000 to $325,000 per farm. Meanwhile, Iowa farm debt had risen to $16 bil-lion-a figure larger than the national debt of Peru!

Overproduction at Home and Abroad. It is

almost inevitable that farmers will produce too much. If the price of a certain crop is high, many thousands of farmers will try to increase their output of that commodity, and farmers who had been producing something else will switch to that item. Since farmers are generally scattered, poorly organized, and producing on an individual rather than a group basis, each will be thinking of his or her own gain and will pay little attention to the fact that great numbers of competitors are doing the same thing.

In time, the market will be flooded as farmers strive to increase their income by producing more. The results, of course, will be that prices will fall. Instead of discouraging production, however, quite the opposite can happen. Since most of their costs are fixed, many farmers will try to make up for falling prices and cover their costs by producing even greater quantities.