- •15.1. Urban Problems

- •15.2. What Can Be Done?

- •15.3. Poverty in America

- •15.4. Who are the Poor?

- •15.5. The Health-Care Crisis: An Overview

- •15.6. How Can America's Health-Care System Be Improved?

- •15.7. Farmers and their Problems

- •15.8. Economic Sources of the Farm Problem

- •15.9. The Global Connection

- •15.10. Federal Farm Aid

- •15.11. The 1990s and Beyond

- •15.12. Economic Growth and the Environment

- •15.13. Protecting the Environment

- •15.14. Air Pollution

- •15.15. Water Pollution

- •15.16. Land Pollution

- •15.17. The Economic Results of Regulation

- •15.18. The Twin Deficits

CHAPTER 15

SOME CURRENT ECONOMIC PROBLEMS

Overview

As you read this chapter, look for answers to the following questions:

• What economic problems are faced by America's cities and urban centers? What efforts have

been made to solve these problems?

• What has been done to reduce or eliminate the problem of poverty?

• What is the "Health-Care Crisis in America," and what are some possible solutions?

• What is meant by "the farm problem"?

• How can we have economic growth and protect the environment?

• How should trade and budget deficits be dealt with?

Now that you have studied the economic principles and the social and political institutions that shape the American economic system and world economy, you can consider some of the important economic problems facing the U.S. today. In Chapter 1 you learned that economics deals with the world that is and the world that ought to be. Chapter 15 gives you the chance to apply your understanding of the principles of economics to the major problems facing the U.S. economy today.

This text and your Study Guide will help you define and describe the problems. Then it will be up to you to apply what you have learned, determine what ought to be, and explore possible solutions. As you read about these issues, see if you can

• state the problem;

• list alternative solutions; and

• discuss the costs and benefits of each solution.

15.1. Urban Problems

If you lived in the United States before World War I (1914-1918), you probably would have lived on a farm or in a rural community. A rural community is defined as one with fewer than 2,500 residents that is not near any urban community.

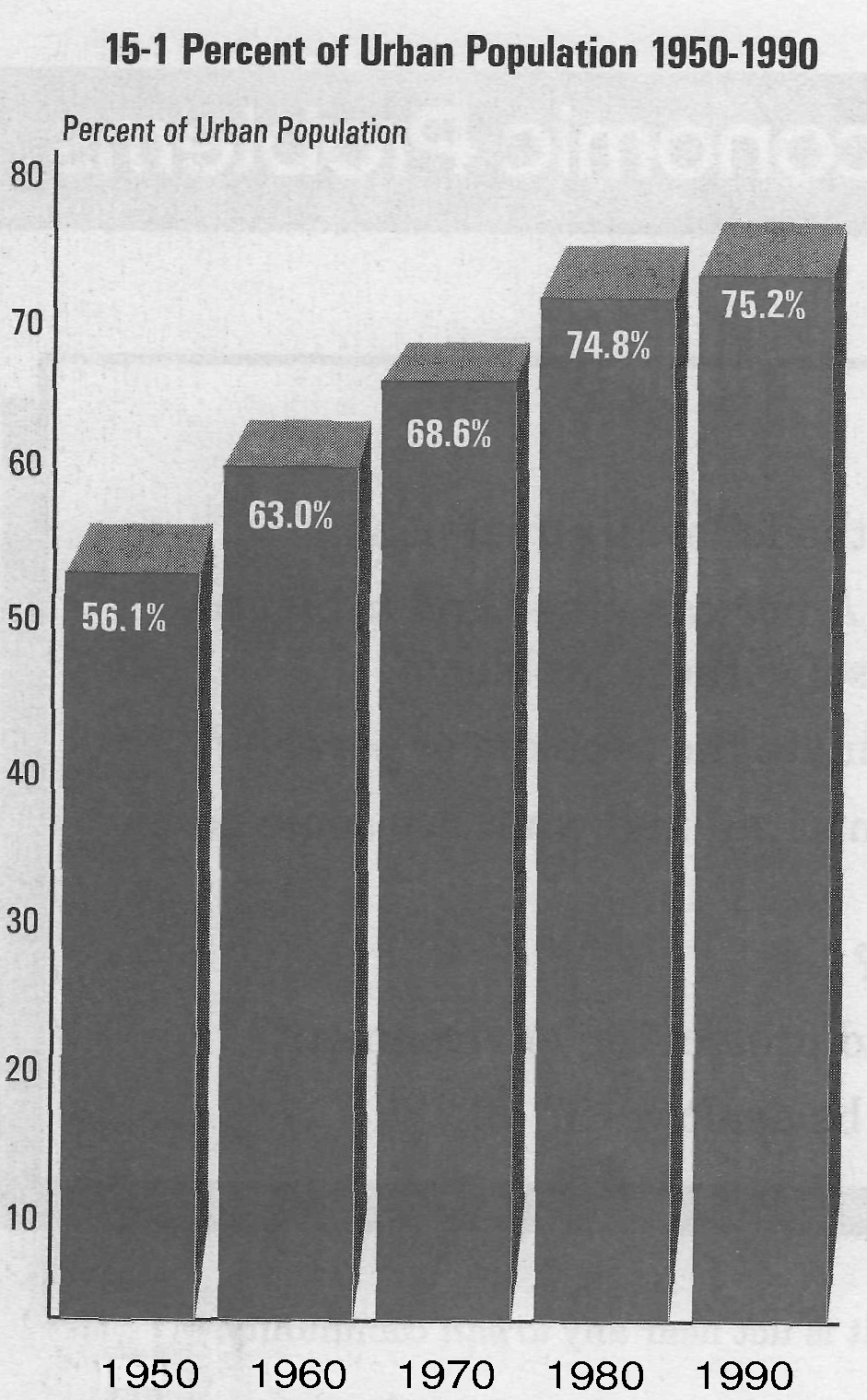

Today about three-quarters of the U.S. population lives in urban communities. The Census Bureau defines an urban community as one with 50,000 or more people living in a central city and its surrounding suburbs.

Increasing industrialization of the United States in the years following World War I favored the growth of cities. Some of the more important advantages cities offered include the following:

• Low transportation costs. Until the 1950s the

major form of U.S. transportation was the railroad. Business developed close to railroad terminals to reduce transportation costs and speed shipments. Meanwhile, the concentration of firms within the relatively small area of a city further reduced travel time among firms and made it convenient for those living in cities to commute to work.

• Better communication facilities. For many years the telegraph and then the telephone were the principal means of communication over long distances. These services were always better in cities than elsewhere. Locally, cities offered ease of communication between firms and their suppliers, banking services, and customers.

• Better services. Hospitals, theaters, schools, department stores, and parks are costly to build and maintain. Consequently, the best will be found where there are large numbers of customers for these services-cities.

But the following technological changes have reduced the importance of such advantages.

• The automobile and truck. By replacing the railroad as the principal form of transportation, the automobile and truck eliminated a major advantage of the central city over the outlying suburbs. Business firms were no longer locked into fixed tracks and railroad timetables. In fact, trucking could operate more efficiently outside the cities where traffic was lighter and parking was not a problem. This change, coupled with the completion of the interstate highway system in the 1960s, removed most of the advantages of being located near a railroad terminal.

• New production methods. Modern technology favors production and assembly of goods on a single floor. Because of the high cost of land, city factories and offices are typically located in multi-storied buildings. Suburban land is far less expensive than land in the central cities. This has made it feasible to build more efficient one-story factories in the suburbs.

• Improvements in communications. Improved telephone service, along with developments in computer technology, eliminated the advantages that cities once offered in electronic communications.

• Personal services. Once found exclusively in

cities, hospitals, theaters, shopping centers, and recreational facilities have followed the movement of the people to the suburbs. Automobiles and high-speed freeways allow people from distant communities to use these services.

Suburban Flight and Urban Blight. When businesses moved to the suburbs, so did large numbers of middle- and upper-income families. The old cities attracted, as they always had, the newest immigrants to America. They also attracted farm workers who lost their jobs in the technological revolution that increased farm productivity.

One result of these population changes was that those groups best able to pay city taxes (the business community and the middle class) were leaving, while those least able (former farm workers and immigrants) were moving in.

The cities were facing a two-fold problem:

• The value of their tax base (the property and people from whom they could collect taxes) was shrinking; while

• Those who were moving in often needed help with

housing, health care, human services, and financial support.

Many of those who moved to the suburbs continue to earn their living in the city. Each morning, roads, trains, and buses are filled to capacity as millions of commuters make their way from the suburbs to the city. There they earn their livelihoods until evening, when in mass exodus they leave for home.

Commuters put additional burdens on the cities, which must provide a variety of services, such as police, fire, sanitation, and hospitals. The commuters, however, pay little or nothing toward the support of the cities because their taxes go to the suburban communities where they live.

The Problems of Urban Finance. City funds come from local taxes and state and federal government grants. So mayors of many large cities frequent their state capitals or Washington in search of funds.

The revenue most cities can raise through taxes is limited. Those families best able to afford taxes can avoid paying them to the cities by moving to the suburbs, and businesses can also relocate.

Cities often adjust their taxes to attract new businesses. For example, a city may offer tax exemptions to firms that move to its area. These exemptions often extend for five or more years. Meanwhile, older, established businesses are expected to continue to pay the prevailing tax rates. In addition, cities set high tax rates on those businesses that cannot easily relocate and low tax rates on those that can.

The Problem of Housing in the Cities. Since the end of World War II, city housing for the poor has deteriorated. Although most reasons for this deterioration are beyond the scope of this book, several of them are directly related to economics.

• Supply, demand and the housing shortage.

Movement of the rural poor into the cities increased the need for housing but did nothing to increase the housing supply. Consequently, the price of low-income housing increased. But many of these "immigrants" could not afford the higher rents. Landlords subdivided apartments, increasing the occupancy rate and profits. As a result, in many instances, low-income people were paying higher rents (per square foot) than the middle class.

• Externalities, housing and other urban problems. Some economic activities may be beneficial (a new office building includes an atrium or plaza that can be enjoyed by the public), others may be harmful (the loss of apartments torn down to build the office). The costs of harmful externalities, such as finding new places to live, must often be paid by those who did not create the problem and are least able to afford them.

Externalities have contributed to the deterioration of the central cities. For example, many landlords have found it more profitable to abandon their buildings and use the loss as a tax write-off than to maintain them. But the presence of abandoned buildings in the middle of the poorest neighborhoods becomes an attraction to drug addicts, criminals, and vandals.

As the number of abandoned and often burned-out buildings increases, people leave the area if they can. Additional landlords abandon their buildings, the crime rate increases, and the harmful effects of externalities multiply.