- •1.1. Morphemes. Structural classification (free and bound), semantic classification (roots and affixes). Morphological classification of words.

- •1.2. Morphemic and word-formation analysis.

- •1.3. Word formation

- •1. Verbs converted from nouns (denominal verbs)

- •2. Nouns converted from verbs (deverbal substantives)

- •Semasiology

- •Valency as the basic principle of word-grouping

- •Etymology

- •Classification of borrowings according to the degree of assimilation

- •Italian borrowings.

Semasiology

What is 'meaning'? This question is not easy to answer. The linguistic science at present cannot give a definition of meaning which is conclusive.

However, we know for sure that the function of the word as a unit of communication is possible because it possesses a meaning. Therefore, among the word's various characteristics, meaning is the most important.

The linguistic discipline which specializes in the study of meaning is called semantics. As with many terms, the term "semantics" is ambiguous because it can stand for the expressive aspect of language in general and for the meaning of one particular word. Semantics has two branches: semasiology and onomasiology. The term semasiology is also ambiguous: in its general meaning it is synonymous to semantics and in its narrow meaning is contrasted to onomasiology, as semasiology? studies meaning of language units in the direction 'from name/sign to concept', while onomasiology studies in the direction 'from thing to name'.

Referential approach to Meaning

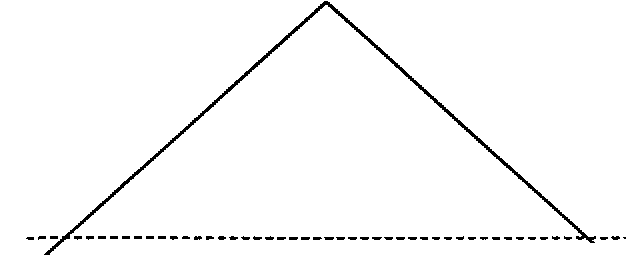

Generally speaking, meaning can be described as a component of the word through which a concept is communicated, in this way endowing the word with the ability of denoting real objects, qualities, actions and abstract notions. The complex and somewhat mysterious relationships between referent (object, thing, etc. denoted by the word), concept (thought, reference) and word (symbol, name, sign) are traditionally represented by the following triangle

Thought or Reference

The dotted line suggests that there is no immediate relation between word and referent: it is established only through concept.

The mechanism by which concepts (i.e. mental phenomena) are converted into words (i.e. linguistic phenomena) and the reverse process are not yet understood or described.

Functional approach to Meaning

The functional approach, popular with structural linguistics, maintains that the word's meaning may be studied only through its relation to other words and not through its relation to either concept or referent. This view may be illustrated by the following: the meaning of the two words sun and sunbathe is different because they function in speech differently, which is clear comparing the contexts they are used.

When comparing two approaches we see that the functional approach is not the alternative, but a complement to the referential theory. It is natural that linguistic investigation must start by collecting a number of samples of contexts.

Methods of studying meaning can be divided into two groups: (1) linguistic and (2) psycholinguistic methods.

(1) Linguistic methods include paradigmatic and syntagmatic methods. In syntagmatically oriented methods different words are studied in one and the same context and one and the same word is observed in different contexts. These are distributional analysis, study of words' combinability, contextual analysis.

Paradigmatically oriented methods are: componential analysis, method of substitution of words.

Types of meaning

The word meaning is not homogeneous but is made of components, which are described as types. Two main types of meaning are the grammatical and the lexical meaning.

The definition of lexical meaning has been given differently in different linguistic schools. In Russia various authors agree that lexical meaning is the realization of concept or emotion by means of a definite language system. This meaning is identical in all forms of the words: love, loves, loving, loved.

Grammatical meaning is the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words, as, e.g. the tense meaning the word-forms of verbs (told, booked, sang) or the meaning of plurality in the word-forms of nouns ( tales, smiles, shoes).

These types of meaning are both abstract, though grammatical is more abstract and generalized. Lexical and grammatical meanings are different in the way the concept is conveyed by them. One concept can be expressed by the lexical meaning and the grammatical meaning. The concept of 'plurality' can be expressed lexically by the word plurality, and grammatically in word-forms - computers, singles, demos.

The lexico-grammatical meaning is the common denominator of all the meanings of words belonging to a lexico-grammatical class of words (parts-of-speech), it is a feature according to which they are grouped together. They are grouped into major word-classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs) and minor word-classes (articles, prepositions, conjunctions, etc.).

All members of major word-classes possess very abstract lexical meaning, e.g., 'thingness or substance' is found in nouns, which have the grammatical meanings of number, case, etc.

Types of semantic components

The modern approach to semantics is based on the assumption that the inner form of the word (i.e. its meaning) presents a structure which is called the semantic structure of the word.

The leading semantic component in the semantic structure of a word is termed denotative component or denotation. It expresses the conceptual (notional) content of a word. E.g.:

denotative component

lonely, adj. - alone, without company

notorious, adj. - widely known

celebrated, adj. - widely known

to glance, v. - to look

to glare, v. - to look.

It is obvious that that the definitions given are incomplete. To give a more or less full picture of the meaning of a word, it is necessary to include additional semantic components which are termed connotations or connotative components. The connotative component is optional, while the denotational is obligatory, because it makes the communication possible. Sometimes it is difficult to draw the demarcation line between them.

There are four types of connotations. They are stylistic, emotional, evaluative and expressive or intensifying.

The stylistic connotation is associations concerning the situation in which the word is uttered, the social circumstances (formal, familiar, etc.), the social relationships between the interlocutors (polite, rough), the type and purpose of communication (learned, poetic, official, etc.).

The effective method of revealing connotations is the analysis of synonymic groups, where the identity of denotational meanings makes it possible to separate the connotational overtones. A classical example for showing stylistic connotations is the noun horse and its synonyms. The word horse is stylistically neutral, its synonym steed is poetic, nag is slangish and gee-gee is baby language.

An emotional or effective connotation is acquired by the word as a result of its frequent use in contexts corresponding to emotional situations or because the referent in the denotative meaning is associated with emotions. E.g. girl (neutral) and girlie (emotive connotation). The word lonely has emotive connotations (melancholy, sad), the word to glare (in anger, rage, etc.).

Evaluative connotation expresses approval or disapproval. E.g. the word notorious possesses negative evaluative connotation, while its synonym celebrated has positive evaluative connotation.

Intensifying connotation expresses exaggeration. E.g. love - adore.

Very often the word has two or three types of connotation. If the word has connotation it is actualized in every context. It differs in this sense from the implicational meaning of the word, which is the implied information associated with the word. It remains a potential until it is realized in some figurative meaning or in a derivative. E.g. a wolf is known to be greedy and cruel but these features are not included in its denotational meaning. But the figurative meaning of this word is -'a cruel greedy person', and the adjective wolfish means 'greedy'.

Phonetic, morphological and semantic motivation of words

The term motivation is used to denote the relationship existing between the phonemic or morphemic composition and structural pattern of the word on the one hand, and its meaning on the other. There are three main types of motivation:

phonetical, morphological, and semantic.

When there is a certain similarity between the sounds that make up the word and those referred to by the sense, the motivation is phonetical. Examples are: hiss, clang, bang, cuckoo. Here belong words imitating the sounds of nature, e.g., noises produces by animals.

A direct connection between the structural pattern of the word and its meaning is called morphological motivation. All one-morpheme words (cry, cloud, go) are non-motivated morphologically. The words ex-wife, rewrite, doer are morphologically motivated.

The degree of motivation may be different. Between complete motivation and lack of motivation there are various grades of partial motivation. Thus, cranberry is partially motivated because of the absence of the lexical meaning in the morpheme cran-.

Semantic motivation is based on the co-existence of direct and figurative meanings of the same word within the same synchronous system. E.g. the word 'cat' denotes a domestic animal, but the figurative meaning of this word or its metaphorical extension is 'a spiteful woman'. Metaphorical extension can be viewed as generalization of the denotational meaning of a word permitting it to include new referents which are in some way are like the original class ofreferents.

Meaning and context

It is common knowledge that context is a powerful preventative against misunderstanding of meanings. E.g., the adjective dull, if used out of context, would mean different things to different people. Only in combination with other words it reveals its actual meaning: a dull student, a dull stare, a dull play, a dull razor-blade, dull weather. Sometimes the minimum context is not enough to reveal the meaning of the word, and it can be interpreted only in a larger context (a second-degree context - Amosova). E.g., The man was large, but his wife was even fatter. The word fatter here serves as a kind of indicator pointing that large describes a stout man and not a big one.

Several types of contexts are distinguished by linguists. One of them is verbal (linguistic), which originally meant what immediately precedes and follows the word. Now verbal context may cover the whole passage, and sometimes the whole book. Linguists also must pay attention to the so-called 'context of situation' (extra-linguistic). It means not only the actual situation in which the utterance occurs, but the entire cultural background against which a speech event has to be set.

Polysemy. Semantic Structure of the word.

It is generally known that most words convey several concepts and thus possess the corresponding number of meanings. A word having several meanings is called polysemantic, and the ability of words to have more than one meaning is described by the term polysemy.

Polysemy is characteristic of the English vocabulary due to the monosyllabic character of English words and the predominance of root words. All word meanings (lexico-semantic variants) taken together form semantic structure of a polysemantic word. There may be no single semantic component common to all the lexico-semantic variants of the word, but every variant has something in common with at least on of the others.

Polysemy is the phenomenon of language not of speech. Polysemy does not interfere with the communicative. function of language because the situation and context cancel all the unwanted meanings.

The main source of polysemy is a change in the semantic structure of the word. Polysemy may also arise from homonymy.

No general or complete scheme of types of lexical meanings as elements of a word's semantic structure has so far been accepted by linguists. This scheme can represented as the system of oppositions:

direct:: figurative

concrete :: abstract

main / primary :: secondary

From the historical point of view we may speak about the following types of meanings: etymological (the earliest known), obsolete (gone out of use), present-day (the most frequent in the present-day language), original (serving as basis for the derived meanings).

The semantic structure of correlated polysemantic words of different languages can never be identical. Words from different languages are felt correlated if their central meaning coincide.

The semantic structure of a word is never static. Its change is a source of the development of the vocabulary.

Causes of Development of new meanings

Two groups of causes: linguistic and extra-linguistic (historical).

(1) Extra-linguistic. Different kinds of changes in a nation's social life, in its culture, knowledge, technology, arts lead to gaps in the vocabulary which should be filled. Newly created objects, new notions, phenomena must be named. We already know of two ways for providing new names: making new words (word-building) and borrowing foreign ones. One more way is to apply old word to a new object or notion.

E.g., when the first textile factories appeared in England, the old word mill was applied to these industrial enterprises. In this way, mill added a new meaning "textile factory".

(2) Linguistic. The development of meaning and a complete change of meaning may be caused through the influence of the other words, mostly synonyms an also ellipses, linguistic analogy.

The Old English verb steorfan meant "to perish". When the verb to die had been borrowed from the Scandinavian, these two synonyms collided, and, as a result, to starve gradually changed into "to die from hunger". This process is called discrimination of synonyms.

Process or nature of development and change of meaning

A necessary condition of any semantic change is some association between the old meaning and the new. There are two kinds of psychological association involved in semantic change: (1) similarity of meaning; (2) contiguity of meaning.

Similarity of meanings or metaphor may be described as a semantic process of associating two referents, one of which in some way resembles the other. This similarity is outward.

E.g., the word star in the basic meaning "heavenly body" developed the meaning "famous actor, singer, etc.". In the same way appeared the meanings the eye of a needle, the neck of a bottle.

Contiguity of meaning or metonymy may be described as the semantic process of associating two referents one of which makes part of the other or is closely connected with it. This connection is real, unlike metaphoric transfer where the resemblance is only in our imagination. The examples of metonymy are: a mink ("mink coat"), ajersy ("knitted shirt or sweater"), silver ("silver medal"). The name of painter is frequently transferred onto one of his pictures: a Matisse = a painting by Matisse.

Results of semantic change

Results of semantic change can be observed in denotational meaning (generalization and specialization of meaning) and in its connotational component (elevation and pejoration of meaning).

The process due to which the word becomes applicable to fewer things but tells more about them is called specialization. E.g., the word deer meant "any beast" but now its meaning is "a certain kind of beast", meat "any food" > "a certain kind of food".

Generalization is the process when the scope of the new notion is wider than that of the original one, whereas the content of the notion is poorer. The word bird changed its meaning from "the young of a bird" to its modem meaning through transference based on contiguity. The second meaning is broader and more general. The word girl in Middle English had the meaning of "a small child of either sex". Then the word underwent the process of transference based on contiguity and developed into the meaning of "a small child of the female sex", so that the meaning was narrowed. But further it gradually broadened its range of meaning to "a young unmarried woman".

Elevation (amelioration) of meaning is the improvement of the connotational component of meaning. E.g., lord: "master of the house, head of the family" > " baronet", lady "mistress of the house, married woman" > "wife or daughter of baronet", knight "manservant" > "noble, courageous man".

Degradation (pejoration) of meaning is the acquisition by the word of some derogatory emotive charge. E.g.. knave "boy" > "swindler, scoundrel", villain "farm-servant" > "vile person", silly " happy" > "foolish".

Causes, nature and result of semantic changes should be regarded as three different but closely connected aspects of the same linguistic phenomenon.

THE PROBLEMS OF COLLOCABILITY AND PHRASEOLOGY