Middle English Grammar: the Noun

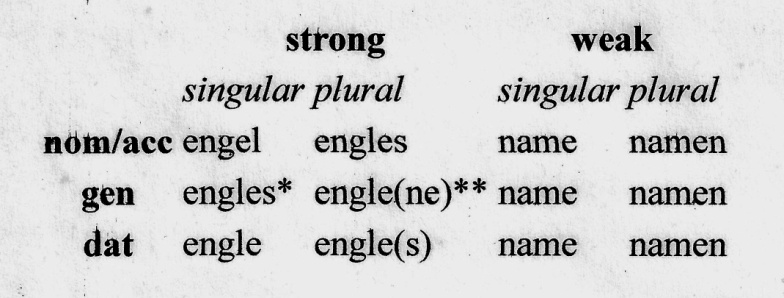

Middle English retains only two distinct noun-ending patterns from the more complex system of inflection in Old English. The early Modern English words engel (angel) and name (name) demonstrate the two patterns:

Some nouns of the engel type have an -e in the nominative/accusative singular, like the weak declension, but otherwise strong endings, Often these are the same nouns that had an -e in the nominative/accusative singular of Old English.

The strong -(e)s plural form has survived into Modern English. The weak -(e)n form is now rare in the standard language, used only in oxen, children, brethren; and it is slightly less rare in some dialects, used in eyen for eyes, shoon for shoes, hosen for hose(s), kine for cows, and been for bees.

Middle English Grammar: the Verb

As a general rule, the first person singular of verbs in the present tense ends in -e ("ich here" — "I hear"), the second person in -(e)st ("J)ou spekest" — "thou speakest"), and the third person in -ej) ("he ^omej)" — "he cometh/he comes"), (p is pronounced like the unvoiced th in "think").

Plural forms vary strongly by dialect, with southern dialects preserving the Old English -ef), Midland dialects showing -en from about 1200 onward and northern forms using -es in the third person singular as well as the plural.

In the past tense, weak verbs are formed by adding an -ed(e), -d(e) or -t(e) ending. These, without their personal endings, also form past participles, together with past-participle prefixes derived from Old English: i-, y- and sometimes bi-.

Strong verbs, by contrast, form their past tense by changing their stem vowel (binden -> bound), as in Modem English.

English was also influenced by the Celtic languages it was displacing, most notably with the introduction of the continuous aspect (to be doing or to have been doing), which is a feature found in many modern languages but developed earlier and more thoroughly in English.

6. Middle English Grammar, the Pronoun

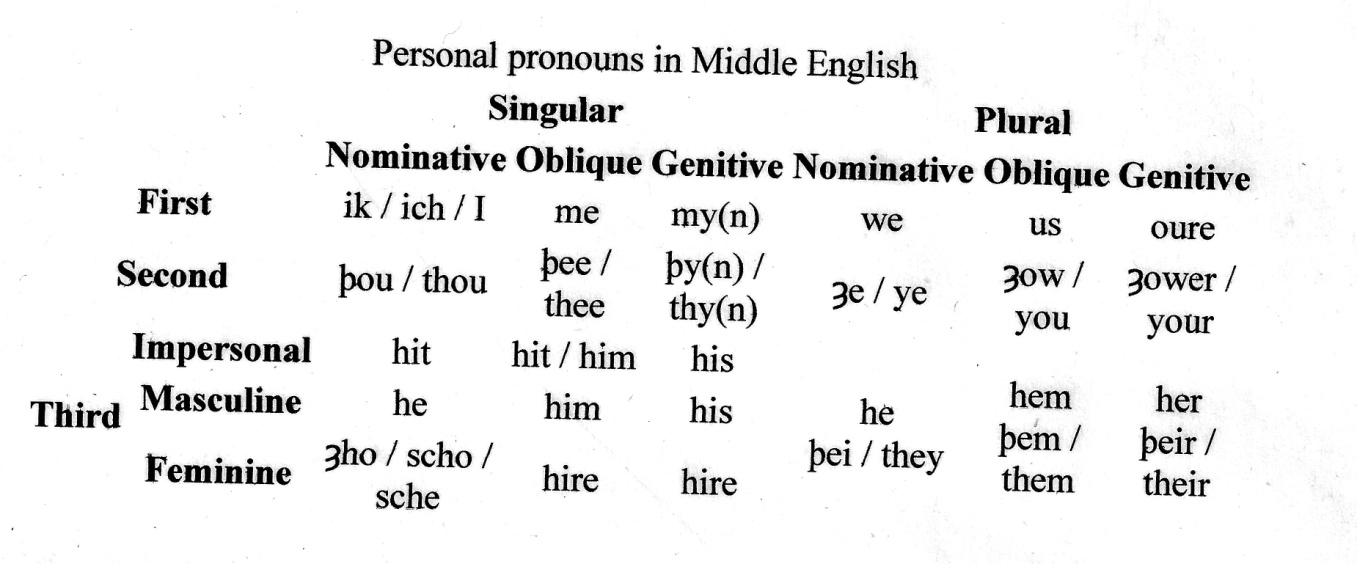

After the Conquest, English retained Old English pronouns, with the exception of the third person plural, a borrowing from Old Norse (the original Old English form clashed with the third person singular and was eventually dropped):

The first and second person pronouns in Old English survived into Middle English largely unchanged, with only minor spelling variations. In the third person, the masculine accusative singular became fhirn\ The feminine form was replaced by a form of the demonstrative that developed into fsche'9 but unsteadily—fheyrf remained in some areas for a long time. The lack of a strong standard written form between the 13th and the 15th centuries makes these changes hard to map. Still, the overall trend was the gradual reduction in the number of different case endings.

7. Middle English Phoinology

Generally, all letters in Middle English words were pronounced. (Silent letters in Modern English generally come from pronunciation shifts, which means that pronunciation is no longer closely reflected by the written form because of fixed spelling constraints imposed by the invention of dictionaries and printing.) Therefore 'knight' was pronounced [Dknift] (with a pronounced <k> and the <gh> as the <ch>

in German fKnechtf), not [Onait] as in Modern English.

In earlier Middle English all written vowels were pronounced. By Chaucer's time, however, the final <e> had become silent in normal speech, but could optionally be pronounced in verse as the meter required (but was normally silent when the next word began with a vowel). Chaucer followed these conventions: - e is silent in 'kowthe*and fThanne\ but is pronounced in 'straunge\ fferne\ fende\ etc. (Presumably, the final <y> is partly or completely dropped in fCaunterbury\ so as to make the meter flow.)

a) ME Consonants were characterized by the following features:

voiceless fricative /hJ had velar (ME thurh) and alveo-palatal (ME niht) allophones;

loss of long consonants (OE mann ) ;

h lost in clusters, OE hlcefdige>ME ladi, OE hnecca>ME necke, OE hrcefn>ME raven;

voiced velar fricative allophone of g (normally a voiced velar stop in OE) became w after 1 and r: OE morgeri>ME morwen, OE sorg>ME sorrow;

OE prefix ge- lost initial consonant and was reduced to y or i: OE genog>ME inough, OE genumen>ME inomen;

unstressed final consonants tended to be lost after a vowel: OE ic>ME i, OE -lic>ME ly;

final -n in many verbal forms (infinitive, plural subjunctive, plural preterite) was lost (remains in some past participles of strong verbs: seen, gone, taken); final -n also lost in possessive adjectives m and thy and indefinite article fanf before words beginning with consonant (-n remained in the possessive pronouns);

w dropped after s or t: OE sweostor> sister, OE swilc>such (sometimes retained in spelling: sword, two; sometimes still pronounced: swallow, twin, swim);

1 was lost in the vicinity of palatal c in adjectival pronouns OE celc, swilc, hwilc, micel> each, such which, much (sometimes remained: /?/c/z, milch);

fricative v tended to drop out before consonant+consonant or vowel+consonant: OE hlaford, hlcefdigi heqfod, hcefde>ME lord, ladi, hed, hadde (sometimes retained; OE heofon, hrcefn, dreflian>heaven, raven, drivel);

final b lost after m but retained in spelling: lamb, comb, climb (remained in medial position: timber, amble); intrusive b after m and before consonant: OE bremel, ncemel, cemerge>ME bremble, nimble, ember;

intrusive d after n in final position or before resonant: OE dwinan, punor > ME dwindle, thunder ; intrusive t after s in final position or before resonant: OE hlysnan, behces > ME listnen, beheste;

initial stops in clusters gn- and kn- still pronounced: ME gnat, gnaw en, knowen, knave;

h often lost in unstressed positions: OE hit>ME it.

b) Characteristic features of ME voxels:

loss of OE y and ae: y unrounded to i; ae raised toward e or lowered toward a;

all OE diphthongs became pure vowels; French loanwords added several new diphthongs (e.g. OF point, bouillir, noyse > ME point, boille, noise) and contributed to vowel lengthening; diphthongs resulted from vocalization of w, y, and v between vowels;

already in OE short vowels tended to lengthen before certain consonant clusters OE climban, feld> ME climbe, feld;

lengthening of short vowels in open syllables (OE gatu, hopa > ME gate, hope) ;

shortening of long vowels in stressed closed syllables, OEsofte, godsibb, sceaphirde> ME softe, godsib, scepherde, exceptions (before -st): OE last, gast, crist>ME last, gost, Christ; if two or more unstressed syllables followed the stressed one, the vowel of the stressed syllable was shortened (Christ/Christmas [ME Christesmesse], break/breakfast [ME brekefast]); some remnants of distinctions caused by lengthening or shortening in open and closed syllables: five/fifteen, wise/wisdom; in weak verbs, the dental ending closed syllables: hide/hid, keep/kept, sleep/slept, hear/heard;

loss of unstressed vowels: unstressed final -e was gradually dropped, though it was probably often pronounced; -e of inflectional endings also being lost, even when followed by consonant (as in -es, eth, ed) (e.g. breath/breathedexceptions: wishes, judges, wanted, raided; loss of -e in adverbs made them

identical to adjective, hence ambiguity of plain advertee.g. hard, fast, final -e in French loanwords not lost because of French final stress, hence cite>city, pitrete>purity.