Атлас по рентгенологии травмированных собак и кошек / an-atlas-of-radiology-of-the-traumatized-dog-and-cat

.pdf

262 Radiology of Abdominal Trauma

Case 3.33

3

Noncontrast

Signalment/History: “Blue” was a 3-year-old, female Great Dane with a history of surgical repair of a perianal fistula three months previously.

Physical examination: Drainage from a perianal tract was evident on presentation.

Radiographic procedure: Studies were made of the pelvic region and injection of the draining tract with a positive contrast agent was performed.

Radiographic diagnosis: The rectum was constricted 3 cm from the anus. No evidence of skeletal injury could be seen.

The positive contrast agent injected into the tract filled multiple saccules within the perianal tissue, principally on the right side. Importantly, the contrast agent identified a fistulous tract that entered the rectum (arrows), where it partially surrounded the fecal material.

Treatment/Management: The case was treated medically without good recovery. The owners rejected the offer of surgical correction feeling that the first surgery should have been successful.

Urethral injury 263

3

Contrast

264 Radiology of Abdominal Trauma

Case 3.34

3

Noncontrast

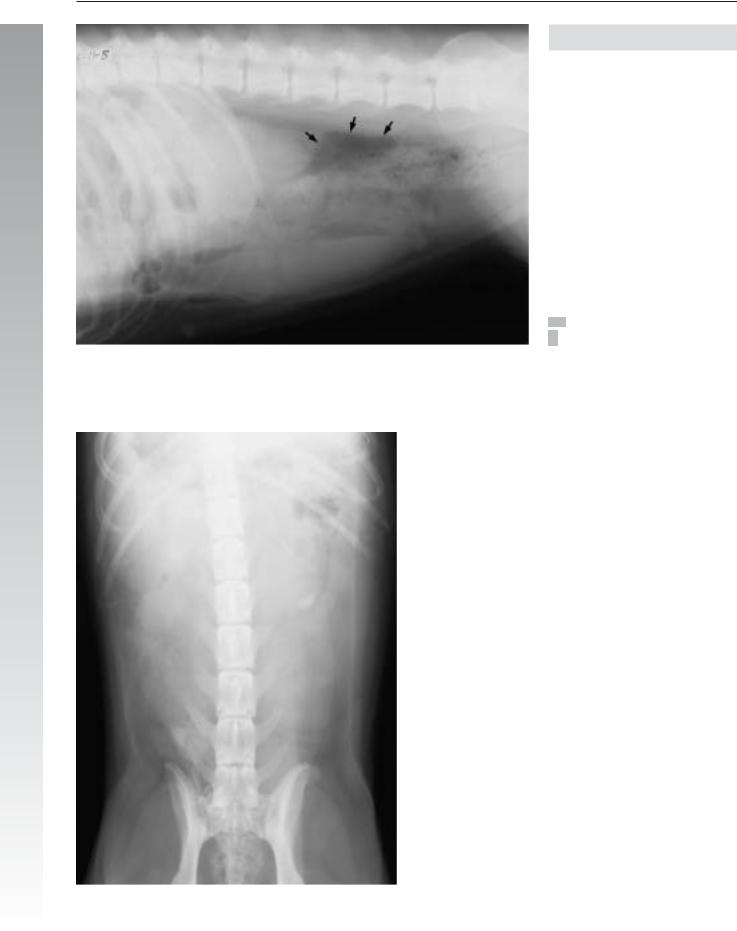

Signalment/History: “Nola” was a 4-year-old, female German Shepherd Dog being examined because of problems related to past pregnancies in which only a small number of puppies had been produced, some of which were nonviable.

Radiographic procedure: Studies of the abdomen were made, followed by contrast studies of the uterus.

Radiographic diagnosis: Intraperitoneal air was noted in large pockets (arrows). An enlarged splenic shadow was seen.

Radiographic diagnosis (contrast study): A catheter was placed into one uterine horn and an oily contrast agent was injected. The radiographs showed intraperitoneal spread of the contrast agent indicative of a uterine tear.

Radiographs made four days later showed a delay in the absorption of the contrast agent. An iodinated product in a water base such as used in urography would have more resorbed quickly.

Treatment/Management: The patient was treated medically. It is interesting that “Nola” delivered seven viable puppies three months following the detection of the uterine injury.

Urethral injury 265

3

Contrast

266 Radiology of Abdominal Trauma

3.2.8Postsurgical problems

Case 3.35

3

Noncontrast

Signalment/History: “Tilly” was a 7-year-old, female Yorkshire Terrier. A post-dystocia ovariohysterectomy had been performed eight days earlier at the referring hospital. A second operation at the same hospital was performed four days afterwards and had been required to remove both incorrectly placed aortic and ureteral ligations. Normal renal function did not return and “Tilly” was referred for studies to evaluate her renal function.

Radiographic procedure: Radiographic studies of the abdomen were performed, followed by a urogram.

Radiographic diagnosis (noncontrast): An overall loss of serosal detail was thought to be secondary to postsurgical effusion, peritonitis, or urine leakage. Multiple, metallic staples were present along the ventral abdominal wall. ECG pads were noted on the lateral abdominal wall.

Postsurgical problems 267

3

Urogram

Radiographic diagnosis (urogram): A hydronephrosis of the right renal pelvis and hydroureter of the right proximal ureter were probably a consequence of the ligated ureter. Leakage of contrast agent from the right mid-ureter into both the retroperitoneal and peritoneal spaces indicated a ruptured ureter (arrows). The left kidney and ureter appeared to have near-normal function. The persistent loss of serosal detail continued to suggest peritoneal fluid due to postsurgical effusion, peritonitis, or urine leakage. The balloon tip of a Foley catheter lay within the urinary bladder (arrow).

Treatment/Management: Because of the ureteral injury, a right nephrectomy was performed and “Tilly” was eventually discharged to her owners.

268 Radiology of Abdominal Trauma

Case 3.36

3

Day 1

Signalment/History: “Smokey” was a 12-year-old, female

German Shepherd with abdominal pain.

Physical examination: A mid-abdominal mass was palpated.

Radiographic procedure: Abdominal radiographs were made.

Radiographic diagnosis (day 1): A 4-cm, right-sided, fluid-dense mass situated in the caudal abdomen had flecks of calcification scattered throughout it, suggesting a granuloma or tumor. The loss of contrast between the abdominal organs indicated a minimal fluid accumulation that might have been due to an effusion, hemorrhage, or peritonitis. No bowel distention was evident. The right renal shadow appeared smaller than expected.

Postsurgical problems 269

3

Day 6

Radiographic diagnosis (day 6): The radiographic features were the same as on day 1. The mass lesion had stayed in the same location within the abdomen.

Treatment/Management: The mass lesion was removed surgically and was a retained surgery sponge incorporated within multiple adhesions.

Comments: Abdominal tumors in general do not contain mineralized tissue, which are more suggestive of a chronic inflammatory lesion.

270 Radiology of Musculoskeletal Trauma and Emergency Cases

Chapter 4

Radiology of Musculoskeletal Trauma and Emergency Cases

4.1Introduction

Trauma is defined as a suddenly applied physical force that results in anatomic and physiologic alterations. The injury varies with the amount of force applied, the means by which it is applied, and the musculoskeletal organs affected. The event can be focal or generalized affecting a single bone or joint, or multiple sites. The effect of the injury to the musculoskeletal system can vary and result in a patient with apparently minimal

4 injury characterized by lameness or inability to bear weight, a patient who is paralyzed, or a patient who is in severe shock. The patient may be presented immediately following the trauma or presentation may be delayed because of the absence of the animal from home or because of the hesitancy or inability of the owners to recognize the injury.

Most trauma cases are accidents in which the patient is struck by a moving object such as a car, bus, truck, or bicycle. The nature of the injury varies depending on whether the patient is thrown free, crushed by a part of the vehicle passing over it, or is dragged by the vehicle. Other types of trauma result from the patient falling with the injury depending on the distance of the fall and the nature of the landing. A unique injury occurs when dogs jumping from the back of a moving vehicle fall only a short distance, because the trauma results from the animal hitting the road at a high speed. This type of injury is severely complicated when the animal has been restrained by a rather long rope or leash in the back of the truck, which causes the patient to be dragged behind the vehicle and a form of “degloving” or “sheering” injury results. Other possibilities of trauma occur when the patient has been hit by a falling object, or is kicked or struck by something. Bite wounds constitute a frequent cause of injury in both small and large patients and can be complicated by a secondary osteomyelitis that develops later. Penetrating injuries are a separate classification of injury and can be due to many types of projectiles. Gunshots are a most common cause of trauma in certain societies (see Chap. 6). Abuse is a specific classification of trauma and should be suspected in certain type of injuries (see Chap. 7).

Emergency cases, i.e. those that are life threatening, are not frequently seen as the result of musculoskeletal injury. A special group consists of those patients with spinal injuries, where emergency treatment may be required and a specific method of movement of the patient is necessary in order to avoid additional injury to the spinal cord. Patients with head injuries are uncommon, though such traumas often result in the death of the animal. If the trauma only affects the more rostral portion of the head, it results in injury to the nasal or frontal portions and the injury, while obviously deforming, is not usually life threatening.

Musculoskeletal radiology can be performed relatively cheaply, quickly, and safely, thus providing rapid results on which to base the next set of decisions. Radiographic studies can usually be made on the non-sedated or non-anesthetized patient. When and how to use these techniques is often rather obvious (see Table 4.1).

Table 4.1: Use of radiographic examination in a traumatized or emergency patient suspected of having musculoskeletal injury

1.Radiograph permits selection of the area to study

a.possible to survey the entire body:

I.when a complete clinical history of the trauma is not available

II.when a thorough physical examination cannot be conducted

III.more accurately than is possible by physical examination alone

b.possible to limit study to the area of suspected injury only

c.use of comparison studies is helpful in skeletally immature patients

d.nature of injury may limit the study to a single projection

2.Radiography can be performed

a.in a non-traumatic manner

b.within a few minutes

c.with minimal cost to the client

d.with relative ease in many patients

3.Radiographic diagnosis permits the detection of

a.more than one lesion

b.which lesions are of greatest clinical importance

4.Radiographic diagnosis enables decisions to be made about:

a.the sequence of treatment

b.the prognosis

c.the expected time and cost of treatment

5.Radiography identifies complicating factors such as

a.pre-existing

I.non-traumatic lesions

II. traumatic lesions

III.arthrosis in the injured limb

b.soft tissue injury

6.Radiography provides a permanent clinical record to enable:

a.an owner to better understand

I.the lesions

II.the proposed treatment

b.the clinician

I.to evaluate the treatment

II.to review the radiographs

III.to seek further assistance by referral of the radiographs to an expert

7.Radiography permits

a.assessment of the effectiveness of therapy in the event that clinical improvement is delayed

b.determination of the time for removal of fixation devices

c.determination of the time of discharge from the clinic

d.determination of the time for a return to full physical activity

Introduction 271

Radiology is the most commonly used method of examination of a traumatized patient with a suspected injury to either bone or joint. The use of radiology varies with the nature of the injury and ranges from a single survey radiograph to the use of a contrast study such as myelography in a suspected spinal injury. Radiology used in the evaluation of suspected injury to the appendicular skeleton is common and those patients constitute the major portion of this section.

The physical examination in fracture/luxation cases is informative and helps direct the radiographic examination. Bite and gunshot wounds have associated soft tissue lesions that are suggestive of those types of trauma. In certain patients unable to bear weight on a limb, attention is obviously directed toward that limb. In those patients with a less severe injury or chronic lameness, the role of trauma is not as obvious and many types of bone or joint disease could be the cause of a lameness incorrectly thought to be the result of trauma. Often, the physical examination in a trauma patient is compromised because of pain or non-cooperation, and errors in interpretation are frequent. The greatest error made in the examination of trauma patients is the tendency to direct all attention to the site of the most obvious injury and limit the examination of the remainder of the animal. For example, this can lead to the diagnosis of a pelvic fracture while ignoring a ruptured urinary bladder, or the treatment of a femoral fracture while ignoring a diaphragmatic hernia. The nature of the trauma can indicate the requirement for whole body radiographs. This need depends on the questionable nature of the clinical history and your failure to obtain adequate information from your physical examination. The positive value of whole body radiographs cannot be overstressed.

The most informative radiographic technique in the evaluation of suspected musculoskeletal injury includes two views and includes the joints both proximal and distal to the site of the suspected injury. In an examination performed on a skeletally immature patient, comparison radiographs of the opposite limb make the evaluation of the growth regions in a bone more accurate. Because of the trauma, positioning of a limb in the usual manner for radiography may be painful or damaging to the surrounding tissues and compromises are often required. It may be better medicine to rely on the radiograph of a malpositioned limb rather than having to fight with the patient in an effort to achieve a more acceptable radiographic positioning. Positioning errors are especially frequent with pelvic and femoral injuries, where the perfect VD view with the pelvic limbs extended is too painful and it has therefore often to be done with the limbs held in flexion with both in a similar position.

Radiographic diagnoses result from studying skeletal radiographs that present information in a single plane, and which includes only a descriptive gross image of the complex threedimensional cortical and cancellous structures found in a bone.

The radiographic image does not record the exact trabecular and cortical anatomic details, but instead depicts photographic patterns that are produced by overlay, groupings, and accumulations of large numbers of the fine and coarse trabeculae, as well as the enclosing cortical bone. In a bone with a complicated morphology, the radiographic interpretation of a lesion becomes more difficult.

In contrast to thoracic and abdominal trauma, radiographic diagnosis is more specific in trauma patients with musculoskeletal damage and may include a detailed description of the fracture and its location in a bone. In comparison, for example, the presence of fluid can be revealed in the thorax study of a patient, however, the type of fluid can only be speculated upon until further tests are undertaken.

Differential diagnosis is not often necessary in musculoskeletal |

4 |

trauma. However, it does become important when trauma is superimposed over previous bone or joint disease, or when the clinical history is incorrect and the bone lesions have not been induced by trauma. In certain patients when indicated, this section will include a full discussion of the differential diagnosis.

The treatment/management is often predictable in a trauma patient and has usually been kept brief in the text, consisting of a comment concerning the reduction and stabilization of a fracture. This part of the case discussion is not explored to any great depth in this book since it belongs more appropriately in an orthopedic text. In other patients, the handling of the patient includes specific comments that are thought to be of interest to the reader.

The outcome of the case is often known and a comment relative to this is made for the reader. When appropriate, the results of surgical biopsy or necropsy are included. In certain cases, additional clinical history is known and presented for the reader’s interest. However, the specific time required for fracture healing is dependent on the particular injury, the status of the patient, and the type of the fracture and method of stabilization. Therefore, it is impossible to make specific statements about the expected time for fracture healing. Generally, if a time is offered, it only suggests the time expected for a fracture of a particular type.

Discussion of the case presented might include comments on specific changes in protocol that were of assistance in diagnosis, or it might include errors that were made in the manner in which the case was handled. Apparent errors in clinical judgment as seen in retrospect are actually often determined by the lack of freedom offered by an owner as treatment of the case progresses. Also included in the discussion are suggestions that might have provided additional information of value in diagnosis or treatment.