Product Life Cycle

The Product Life Cycle (PLC) is used to map the lifespan of a product. There are generally four stages in the life of a product. These four stages are the Introduction stage, the Growth stage, the Maturity stage and the Decline stage. The following graph illustrates the four stages of the PLC:

There is no set time period for the PLC and the length of each stage may vary. One product's entire life cycle could be over in a few months. Another product could last for years. Also, the Introduction stage may last much longer than the Growth stage and vice versa.

The Four Stages of the Product Life Cycle

1. Introduction: The Introduction stage is probably the most important stage in the PLC. In fact, most products that fail do so in the Introduction stage. This is the stage in which the product is initially promoted. Public awareness is very important to the success of a product. If people don't know about the product they won't go out and buy it. There are two different strategies you can use to introduce your product to consumers. You can use either a penetration strategy or a skimming strategy. If a penetration strategy is used then prices are set very high initially and then gradually lowered over time. This is a good stategy to use if there are few competitors for your product. Profits are high with this strategy but there is also a great deal of risk. If people don't want to pay high prices you may lose out. The second pricing strategy is a skimming strategy. In this case you set your prices very low at the beginning and then gradually increase them. This is a good strategy to use if there are alot of competitors who control a large portion of the market. Profits are not a concern under this strategy. The most important thing is to get you product known and worry about making money at a later time.

2. Growth: If you are lucky enough to get your product out of the Introduction stage you then enter this stage. The Growth stage is where your product starts to grow. In this stage a very large amount of money is spent on advertising. You want to concentrate of telling the consumer how much better your product is than your competitors' products. There are several ways to advertise your product. You can use TV and radio commercials, magazine and newspaper ads, or you could get lucky and customers who have bought your product will give good word-of-mouth to their friends/family. If you are successful with your advertising strategy then you will see an increase in sales. Once your sales begin to increase you share of the market will stabilize. Once you get to this point you will probably not be able to take anymore of the market from your competitors.

3. Maturity: The third stage in the Product Life Cycle is the maturity stage. If your product completes the Introduction and Growth stages then it will then spend a great deal of time in the Maturity stage. During this stage sales grow at a very fast rate and then gradually begin to stabilize. The key to surviving this stage is differentiating your product from the similar products offered by your competitors. Due to the fact that sales are beginning to stabilize you must make your produc stand out among the rest.

4. Decline: This is the stage in which sales of your product begin to fall. Either everyone that wants to has bought your product or new, more innovative products have been created that replace yours. Many companies decide to withdrawal their products from the market due to the downturn. The only way to increase sales during this period is to cut your costs reduce your spending. Very few products follow the same cycle. Many products don't even make it through all four stages. Some stages even bypass stages. For example, one product may go straight from the Introduction stage to the Maturity stage. This is the problem with the PLC. There is no set way for a product to go. Therefore, every product requires a great deal of research and close supervision throughout its life. Without proper research and supervision your product will probably never get out of the first stage. Supply and demand

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

![]()

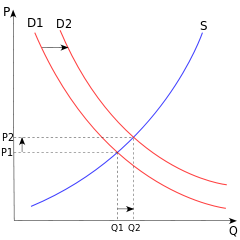

The price P of a product is determined by a balance between production at each price (supply S) and the desires of those withpurchasing power at each price (demand D). The diagram shows a positive shift in demand from D1 to D2, resulting in an increase in price (P) and quantity sold (Q) of the product.

In microeconomics, supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a market. It concludes that in a competitive market, the unit price for a particular good will vary until it settles at a point where the quantity demanded by consumers (at current price) will equal the quantity supplied by producers (at current price), resulting in an economic equilibrium for price and quantity.

The four basic laws of supply and demand are:[1]

If demand increases and supply remains unchanged, a shortage occurs, leading to a higher equilibrium price.

If demand decreases and supply remains unchanged, a surplus occurs, leading to a lower equilibrium price.

If demand remains unchanged and supply increases, a surplus occurs, leading to a lower equilibrium price.

If demand remains unchanged and supply decreases, a shortage occurs, leading to a higher equilibrium price.

|

|

Graphical representation of supply and demand

Although it is normal to regard the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied as functions of the price of the good, the standard graphical representation, usually attributed to Alfred Marshall, has price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis, the opposite of the standard convention for the representation of a mathematical function.

Since determinants of supply and demand other than the price of the good in question are not explicitly represented in the supply-demand diagram, changes in the values of these variables are represented by moving the supply and demand curves (often described as "shifts" in the curves). By contrast, responses to changes in the price of the good are represented as movements along unchanged supply and demand curves.

Supply schedule

A supply schedule is a table that shows the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity supplied. A supply curve is a graph that illustrates that relationship between the price of a good and the quantity supplied .

Under the assumption of perfect competition, supply is determined by marginal cost. Firms will produce additional output while the cost of producing an extra unit of output is less than the price they would receive.

By its very nature, conceptualizing a supply curve requires the firm to be a perfect competitor, namely requires the firm to have no influence over the market price. This is true because each point on the supply curve is the answer to the question "If this firm is faced with this potential price, how much output will it be able to and willing to sell?" If a firm has market power, its decision of how much output to provide to the market influences the market price, then the firm is not "faced with" any price, and the question is meaningless.

Economists distinguish between the supply curve of an individual firm and between the market supply curve. The market supply curve is obtained by summing the quantities supplied by all suppliers at each potential price. Thus, in the graph of the supply curve, individual firms' supply curves are added horizontally to obtain the market supply curve.

Economists also distinguish the short-run market supply curve from the long-run market supply curve. In this context, two things are assumed constant by definition of the short run: the availability of one or more fixed inputs (typically physical capital), and the number of firms in the industry. In the long run, firms have a chance to adjust their holdings of physical capital, enabling them to better adjust their quantity supplied at any given price. Furthermore, in the long run potential competitors can enter or exit the industry in response to market conditions. For both of these reasons, long-run market supply curves are flatter than their short-run counterparts.

The determinants of supply are:

Production costs, how much a good costs to be produced

The technology used in production, and/or technological advances

Firms' expectations about future prices

Number of supplie

editDemand schedule

A demand schedule, depicted graphically as the demand curve, represents the amount of some good that buyers are willing and able to purchase at various prices, assuming all determinants of demand other than the price of the good in question, such as income, tastes and preferences, the price of substitute goods, and the price of complementary goods, remain the same. Following the law of demand, the demand curve is almost always represented as downward-sloping, meaning that as price decreases, consumers will buy more of the good.[2]

Just like the supply curves reflect marginal cost curves, demand curves are determined by marginal utility curves.[3] Consumers will be willing to buy a given quantity of a good, at a given price, if the marginal utility of additional consumption is equal to the opportunity cost determined by the price, that is, the marginal utility of alternative consumption choices. The demand schedule is defined as the willingness and ability of a consumer to purchase a given product in a given frame of time.

It is aforementioned, that the demand curve is generally downward-sloping, there may be rare examples of goods that have upward-sloping demand curves. Two different hypothetical types of goods with upward-sloping demand curves are Giffen goods (an inferior but staple good) and Veblen goods (goods made more fashionable by a higher price).

By its very nature, conceptualizing a demand curve requires that the purchaser be a perfect competitor—that is, that the purchaser has no influence over the market price. This is true because each point on the demand curve is the answer to the question "If this buyer is faced with this potential price, how much of the product will it purchase?" If a buyer has market power, so its decision of how much to buy influences the market price, then the buyer is not "faced with" any price, and the question is meaningless.

Like with supply curves, economists distinguish between the demand curve of an individual and the market demand curve. The market demand curve is obtained by summing the quantities demanded by all consumers at each potential price. Thus, in the graph of the demand curve, individuals' demand curves are added horizontally to obtain the market demand curve.

The determinants of demand are:

Income

Tastes and preferences

Prices of related goods and services

Consumers' expectations about future prices and incomes that can be checked

Number of potential consumers

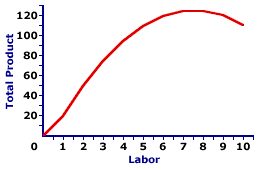

TOTAL PRODUCT CURVE:

A curve that graphically represents the relation between total production by a firm in the short run and the quantity of a variable input added to a fixed input. When constructing this curve, it is assumed that total product changes from changes in the quantity of a variable input (like labor), while other inputs (like capital) are fixed. This is one of three key product curves used in the analysis of short-run production. The other two are marginal product curve and average product curve.

The total product curve illustrates how total product is related to a variable input. While the standard analysis of short-run production relates total product to the variable use of labor, a total product curve can be constructed for any variable input. A more general mathematical concept capturing the relation between total product and its assorted inputs, both variable and fixed, can be found in the production function.

Total Product Curve |

|

The most distinctive feature is the shape of this total product curve. The curve emerges steeply from the origin (no workers produce no tacos), then begins to flatten, and eventually drops off. The curve reaches its peak of 125 Gargantuan Tacos at both 7 and 8 workers.

To the left of this peak, extra workers increase the production of tacos and to the right extra workers reduce total taco production.

While it might not be totally obvious from the diagram, the slope of this curve becomes increasingly steeper for the first two workers, then gradually flattens for the next five workers before finally turning negative. The changing slope of this curve is the direct result of increasing marginal returns that gives way to decreasing marginal returns and the law of diminishing marginal returns.

One reason to take note of the shape of this curve is that other "natural" relations, both within economics and beyond, follow a similar pattern. A graph of the total utility derived from the consumption of several Hot Momma Fudge Bananarama Ice Cream Sundaes has a similar shape. So too does the plot of a person's life cycle of total income by age. In fact, this curve can be used to represent the life cycle of many natural phenomena, such as the growth of a tree, the public's adoption of a new product innovation, or the number of weeds in Duncan Thurly's backyard as spring days turn to summer.