Prosody

The sound system enables us to express meaning in speech in both verbal and non-verbal ways. Verbal meaning ('what we say') relies on vowels and consonants to construct words, phrases, and sentences. Nonverbal meaning ('the way that we say it') makes use of such factors as intonation, rhythm, and tone of voice to provide speech with much of its structure and expressiveness. As the old song wisely says, 'it ain't what you say, it's the way that you say it'. So often, it is the nonverbal meaning which is the critical element in a communication.

Prosodic features

How many 'ways' are there to say things? The chief possibilities are dictated by the main auditory properties of sound: pitch, loudness, and speed. These properties, used singly or in combination (in the form of rhythm), and accompanied by the distinctive use of silence (in the form of pause), make up the prosody or prosodic features of the language.

The most important prosodic effects are those conveyed by the linguistic use of pitch movement, or melody — the intonation system. Different pitch levels (tones) are used in particular sequences (contours) to express a wide range of meanings. Some of these meanings can be shown in writing, such as the opposition between statement (They're ready) and question (They're ready?), but most intonational effects have no equivalents in punctuation, and can be written down only through a special transcription.

Loudness is used in a variety of ways. Major differences of meaning (such as anger, menace, excitement) can be conveyed by using an overall loudness level. More intricately, English uses variations in loudness to define the difference between strong and weak (stressed and unstressed) syllables. The stress pattern of a word is an important feature of the word's spoken identity: thus we find nation, not nation; nationality, not nationality. There may even be contrasts of meaning partly conveyed by stress pattern, as with record (the noun) and record (the verb). Stress patterns make an important contribution to spoken intelligibility, and foreigners who unwittingly alter word stress can have great difficulty in making themselves understood.

• Varying the speed (or tempo) of speech is an important but less systematic communicative feature. By speeding up or slowing down the rate at which we say syllables, words, phrases, and sentences, we can convey several kinds of meaning, such as (speeding up) excitement and impatience, or (slowing down) emphasis and thoughtfulness. There is a great deal of difference between No said in a clipped, definite tone ('Nope') and No said in a drawled, meditative tone ('No-o-o'). And grammatical boundaries can often be signalled by tempo variation, as when a whole phrase is speeded up to show that it is functioning as a single word (a take-it-or-leave-it situation).

THE FUNCTIONS OF INTONATION

Emotional Intonation's most obvious role is to express attitudinal meaning — sarcasm, surprise, reserve, impatience, delight, shock, anger, interest, and thousands of other semantic nuances.

Grammatical Intonation helps to identify grammatical structure in speech, performing a role similar to punctuation. Units such as clause and sentence often depend on intonation for their spoken identity, and several specific contrasts, such as question/statement, make systematic use of it.

Informational Intonation helps draw attention to what meaning is given and what is new in an utterance. The word carrying the most prominent tone in a contour signals the part of an utterance that the speaker is treating as new information: I've got a new pen, I bought three books.

Textual Intonation helps larger units of meaning than the sentence to contrast and cohere. In radio news-reading, paragraphs of information can be shaped through the use of pitch. In sports commentary, changes in prosody reflect the progress of the action.

Psychological Intonation helps us to organize speech into units that are easier to perceive and memorize. Most people would find a sequence often numbers (4,7, 3, 8, 2, 6,4,8, 1, 5) difficult to recall; the task is made easier by using intonation to chunk the sequence into two units (4,7,3,8,2/6,4,8,1,5).

Indexical Intonation, along with other prosodic features, is an important marker of personal or social identity. Lawyers, preachers, newscasters, sports commentators, army sergeants, and several other occupations are readily identified through their distinctive prosody.

RHYTHM

Features of pitch, loudness, speed, and silence combine to produce the effect known as speech rhythm. Our sense of rhythm is a perception that there are prominent units occurring at regular intervals as we speak. In the main tradition of English poetry, this regularity is very clear, in the form of the metrical patterns used in lines of verse. The iambic pentameter, in particular, with its familiar five-fold te-tum pattern (The curfew tolls the knell of parting day), has given the language its poetic heartbeat for centuries.

All forms of spoken English have their rhythm, though in spontaneous speech it is often difficult to hear, because hesitations interfere with the smooth flow of the words. In fluent speech, however, there is a clear underlying rhythm. This is often called a stress-timed (or isochronous) rhythm — one based on the use of stressed syllables which occur at roughly regular intervals in the stream of speech. It contrasts with the syllable-timed rhythm of a language such as French, where the syllables have equal force, giving a marked rat-a-tat-a-tat effect.

The history of English is one of stress-timing, though there are signs of the alternative rhythm emerging in parts of the world where English has been in contact with syllable-timed languages, such as India and South Africa. Syllable-timed English, however, is difficult for outsiders to follow, because it reduces the pattern of stress contrast which adds so much to a word's spoken identity. If it is increasing, as some observers suggest, there will be extra problems for the growth of an internationally intelligible standard spoken English.

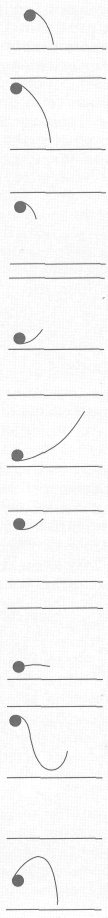

NINE WAYS OF SAYING YES (The direction of pitch movement is shown between two parallel lines, which represent the upper and lower limits of the speaker's pitch range.)

low

fall

low

fall

The most neutral tone; a detached, unemotional statement of fact.

full fall

Emotionally involved; the higher the onset of the tone, the more involved the speaker; choice of emotion (surprise, excitement, irritation) depends on the speaker's facial expression.

mid fall

Routine, uncommitted comment; detached and unexcited.

low rise

Facial expression important; with a 'happy' face, the tone is sympathetic and friendly; with a 'grim' face, it is guarded and ominous.

full rise

Emotionally involved, often disbelief or shock, the extent of the emotion depending on the width of the tone.

high rise

Mild query or puzzlement; often used in echoing what has just been said.

level

Bored, sarcastic, ironic.

fall-rise

A strongly emotional tone; a straight or 'negative' face conveys uncertainty, doubt, or tentativeness; a positive face conveys encouragement or urgency.

rise-fall Strong emotional involvement; the attitude might be delighted, challenging, or complacent.

FUNCTIONAL STYLISTICS AND DIALECTOLOGY.

In the case of Eng. there exists a great diversity in the spoken realization of the lge and particularly in the terms of pronunciation. The varieties of the lge are conditioned by lge communities ranging from small groups to nations. Speaking about nations we refer to the national variants of the lge. Acc. to A.D. Shweizer national lge is a historical category evolving from conditions of economic and political concentration, which ch – zes the formation of a nation. In other words national lge is the lge of a nation, the standard of its form, the lge of a nation’s literature.

It is common to knowledge that lge exists in two forms: written and spoken. Any manifestation of lge by mean of speech is the result of a highly complicated series of events. The literal spoken form has its national pronunciation standard. A “standard” may be defined as “ a social accepted variety of lge established by a codified norm of correctness.

Today all Eng.-speaking nations have their own national variants of pronunciation and each of them has peculiar features that distinguish it from other varieties of Eng. it is generally accepted that for the “Eng. Eng.” it is “Received Pronunciation” (RP); for “the American Eng.” – “General American pronunciation” (GA); for “the Australian Eng” – “Educated Australian”. Standard national pronunciation is sometimes called an “orthoepic norm”. Some phoneticians, however, prefer the term “literary pronunciation”. Though every national variant of Eng. has considerable differences in pronunciation, lexics and grammar, they all have much in common, which gives the ground to speak of one and the same lge – the Eng. lge.

National standards are not fixed and immutable. They undergo constant changes due to various internal and external factors. Pronunciation, above all, is the subject of innovations. Therefore, the national variants of Eng. differ primarily in sound, stress and intonation. There are countries with more than one national lge, the most common case being the existence of 2 national lges on the same territory (Canada). In this case scholars speak about bilingualism in contrast to monolingualism typical of a country with one national lge. Here arises the problem of interference, i.e. “linguistic disturbance, which results from 2 lges (or dialects), coming into contact in a specific situation.”

Every national variety of the lge falls into territorial or regional dialects. Dialects are distinguished from each other by differences in pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary. We must clear that, when we refer to varieties in pronunciation only, we use the word “accent”. So local accents may have features of pronunciation in common and consequently are grouped into territorial and areal accents. These terms should be treated differently when related to different aspect of the lge. There is a great deal of overlap between these terms. For certain geographical, economic, political and cultural reasons one of the dialects becomes the standard lge of the nation and its pronunciation or its accents – the received standard pronunciation. This was the case of London dialect, whose accent became the “RP”.

The standard pronunciation of a country is not homogeneous. It changes in relation to other lges, and also geographical, psychological, social and political influence. As a result of certain social factors in the post – war period – the growing urbanization, spread of education and the impact of mass media – Standard Eng. is exerting an increasing powerful influence on the regional dialects of Great Britain. Recent surveys of British Eng. dialects have revealed that the pressure of Standard Eng. is so strong, that many people are bilingual in a sense that they use an imitation of RP with their teachers and lapse into their native local accent when speaking among themselves. It is called diglossia, i.e. a state of linguistic duality in which the standard literary form of a lge and one of its regional dialects are used by the same individual in different social situations.

Lge and its oral aspect varies with respect to the social context in which it is used. The social differentiation of lge is closely connected with the social differentiation of society. Acc. to A.D. Shweizer “the impact of social factors on lge is not confined to linguistic reflexes of class structure and should be examined with due regard for the meditating role of all class – derived elements – social groups, strata, occupational, cultural and other groups including primary units.” Western sociolinguists such as A.D. Grimshaw, J.Z. Fisher, B. Bernstein, M. Gregory, S. Carrol, A. Hughes, P. Trudgill are oriented towards small groups, viewing them as “microcosmos” of the entire society. Soviet sociolinguists recognize the influence of society upon lge by means of both micro- and macro – sociological factors. Every lge community, ranging from a small group to a nation, has its own social dialect, and consequently its own social accent. British sociolinguists divide the society into following classes: upper class, upper middle class, middle middle class, lower middle class, upper working class, middle working class, lower working class. The validity of this class – n is being debated in sociolinguistics. It is worth to understand that classes are split into different major and minor social groups. Correspondently every social community has its own social dialect and social accent. D.A. Shakhbadova defines social dialects as “varieties spoken by a socially limited number of people.”

So in the light of social criteria lges are characterized by 2 plans of socially conditioned variability – stratificational, linked with social structure, and situational, linked with the social context of lge use. So now we may speak of the “lge situation” in terms of the horizontal and vertical differentiations of the lge, the 1st in accordance with the spheres of social activity, the 2nd – with its situational variability. The lge means are chosen consciously or subconsciously by a speaker acc. to the perception of the situation, in which he finds himself. Hence situational varieties of the lge are called functional dialects or functional styles and situational pronunciation varieties – situational accents or phonostylistics. The lge of its users varies acc. to their individualities, range of intelligibility, cultural habits, sex and age differences. Individual speech of members of the same lge community is known as idiolect.

So lge in serving personal and social needs becomes part of the ceaseless flux of human life and activity. Human communication can’t be comprehended without recognizing mutual dependence of lge and context. The mystery of lge lies in its endless ability to adapt both to the strategies of the individual and to the needs of the community, serving each without imprisoning either. This is what makes sociolinguistics as a science important.

BRITISH ENGLISH.

BEPS (British English Pronunciation Standard and Accents) comprise Eng. Eng. (EE), Welsh Eng. (WE), Scottish Eng. (SE) and Northern Ireland Eng. (NIE).

English English |

Welsh English |

Scottish English |

Northern Ireland English |

||

Southern |

Northern |

Educated Sc. Eng. |

Regional Variants |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

SOUTHERN ENGLISH ACCENTS.

Educated Southern speech is very much near RP accent whereas non – standard accents are very much near Cockney, uneducated London accent. It has been long established that Cockney is a social accent – the speech of working – class areas of the Greater London. There are some pronunciation peculiarities:

VOWELS.

[Λ] is realized as [æ]: blood [blΛd] – [blæid];

[æ] is realized as [e] or [ei]: bag [beg] – [beig];

[i] in word final position sounds as [i:]: city [‘siti] – [‘siti:];

when [o:] is non – final, its realization is much closer, it sounds like [o:]: pause [po:z] – [po:z]; when it is final, it is pronounced as [o:∂]: paw [po:] – [po:∂];

the diphthong [ei] is realized as [æi] or [ai]: lady [l’eidi] – [‘læidi, ‘laidi];

RP [ou] sounds as [ æu]: soaked [‘soukt] – [‘sæukt];

RP [au] may be [æ∂]: now [nau] – [næ∂].

CONSONANTS.

[h] in unstressed position is almost invariably absent;

the contrast between [Θ] and [f] is completely lost: thin [fin];

the contrast between [δ] and [v] is occasionally lost: weather [‘wev];

when [] occurs initially it is either dropped or replaced by [d]: them [(d)∂m];

[l] is realized as a vowel when it precedes a consonant and follows a vowel, or when it is syllabic: milk [mivk], table [teibv]; when the preceding vowel is [o:], [l] may disappears completely;

[ή] is replaced by [n] in word final position: dancing [da:nsin];

[p, t, k] are heavily aspirated, more so than in RP;

[t] is affricated, [s] is heard before the vowel: top [tsop].

NORTHERN AND MIDLAND ACCENTS.

Midland accents (Yorkshire), West Midland and North – West accents have very much in common with Northern ones. Therefore they are combined into one group.

The counties of Northern England are not far from the Scottish border, so the influence of Scottish accent is noticeable, though there are of course many features of pronunciation ch – tic only of northern Eng. regions. The most typical representative of the speech of this area is Newcastle accent.