Consonant Locations

This table gives a brief description of how each English consonant is articulated, using Received Pronunciation (RP) as the reference model.

PLOSIVES

Articulation:

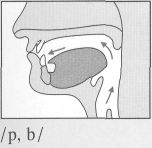

Bilabial

plosives: soft palate raised; complete

closure made by the upper and lower lip; /p/ voiceless,

/b/ voiced (and devoiced in word-final position);

/p/ fortis, /b/ lenis.

Articulation:

Bilabial

plosives: soft palate raised; complete

closure made by the upper and lower lip; /p/ voiceless,

/b/ voiced (and devoiced in word-final position);

/p/ fortis, /b/ lenis.

Articulation:

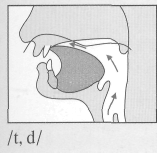

Alveolar

plosives: soft palate raised; complete

closure made by the tongue tip and rims against

the alveolar ridge and side teeth; /t/ voiceless, /d/

voiced (and devoiced in word-final position); /t/ fortis,

/d/ lenis; lip position influenced by adjacent vowel (spread for tee,

meat;

rounded

for too,

foot);

tongue position influenced by a following consonant, becoming

further back (post-alveolar) in try,

dental

in eighth;

when

in final position in a syllable or word, they

readily assimilate to /p, k/ or /b, g/ if followed

by bilabial or velar consonants.

Articulation:

Alveolar

plosives: soft palate raised; complete

closure made by the tongue tip and rims against

the alveolar ridge and side teeth; /t/ voiceless, /d/

voiced (and devoiced in word-final position); /t/ fortis,

/d/ lenis; lip position influenced by adjacent vowel (spread for tee,

meat;

rounded

for too,

foot);

tongue position influenced by a following consonant, becoming

further back (post-alveolar) in try,

dental

in eighth;

when

in final position in a syllable or word, they

readily assimilate to /p, k/ or /b, g/ if followed

by bilabial or velar consonants.

Articulation:

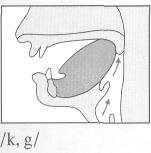

Velar

plosives: soft palate raised; complete

closure made by the back of the tongue against

the soft palate; /k/ voiceless, /g/ voiced (and devoiced

in word-final position); /k/ fortis, /g/ lenis; lip position

influenced by adjacent vowel (spread for keen,

meek, rounded

for cool,

book; also,

quality varies

depending on the following vowel (/k/ in keen

is

much further forward, approaching the hard palate, than

/k/ in car).

Articulation:

Velar

plosives: soft palate raised; complete

closure made by the back of the tongue against

the soft palate; /k/ voiceless, /g/ voiced (and devoiced

in word-final position); /k/ fortis, /g/ lenis; lip position

influenced by adjacent vowel (spread for keen,

meek, rounded

for cool,

book; also,

quality varies

depending on the following vowel (/k/ in keen

is

much further forward, approaching the hard palate, than

/k/ in car).

FRICATIVES

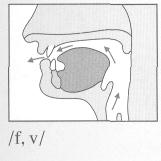

Articulation: Labio-dental fricatives: soft palate raised; light contact made by lower lip against upper teeth; /f/ voiceless, /v/ voiced (and devoiced in word-final position); /f/ fortis, /v/ lenis.

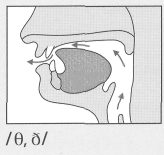

Articulation:

Dental

fricatives: soft palate raised; tongue

tip and rims make light contact with edge and inner surface of upper

incisors, and a firmer contact with

upper side teeth; tip protrudes between teeth for some

speakers; /θ/ voiceless, /ð/ voiced (and devoiced in

word-final position); /θ/

fortis, /ð/ lenis; lip position depends

on adjacent vowel (spread in thief,

heath, rounded

in though,

oath).

Articulation:

Dental

fricatives: soft palate raised; tongue

tip and rims make light contact with edge and inner surface of upper

incisors, and a firmer contact with

upper side teeth; tip protrudes between teeth for some

speakers; /θ/ voiceless, /ð/ voiced (and devoiced in

word-final position); /θ/

fortis, /ð/ lenis; lip position depends

on adjacent vowel (spread in thief,

heath, rounded

in though,

oath).

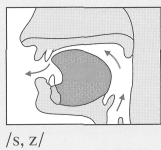

Articulation:

Alveolar

fricatives: soft palate raised; tongue

tip and blade make light contact with alveolar ridge,

and rims make close contact with upper side teeth;

air escapes along a narrow groove in the centre of the tongue; /s/

voiceless, /z/ voiced (and devoiced in word-final

position); /s/ fortis, /z/ lenis; lip position depends

on adjacent vowel (spread in see,

ease,

rounded

in soup,

ooze).

Articulation:

Alveolar

fricatives: soft palate raised; tongue

tip and blade make light contact with alveolar ridge,

and rims make close contact with upper side teeth;

air escapes along a narrow groove in the centre of the tongue; /s/

voiceless, /z/ voiced (and devoiced in word-final

position); /s/ fortis, /z/ lenis; lip position depends

on adjacent vowel (spread in see,

ease,

rounded

in soup,

ooze).

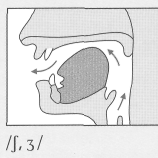

Articulation:

Palato-alveolar

fricatives: soft palate raised;

tongue tip and blade make light contact with alveolar

ridge, while front of tongue raised towards hard

palate, and rims put in contact with upper side teeth; /∫/

voiceless, /z/ voiced (and devoiced in word-final

position); /∫/ fortis, /z/ lenis, but both sounds laxer than

/s/ and /z/; lip rounding influenced by adjacent vowel

(spread in she,

beige,

rounded

in shoe,

rouge),

but

some speakers always round their lips for these sounds.

Articulation:

Palato-alveolar

fricatives: soft palate raised;

tongue tip and blade make light contact with alveolar

ridge, while front of tongue raised towards hard

palate, and rims put in contact with upper side teeth; /∫/

voiceless, /z/ voiced (and devoiced in word-final

position); /∫/ fortis, /z/ lenis, but both sounds laxer than

/s/ and /z/; lip rounding influenced by adjacent vowel

(spread in she,

beige,

rounded

in shoe,

rouge),

but

some speakers always round their lips for these sounds.

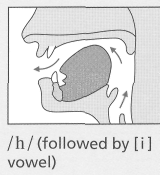

Articulation: Glottal fricative: soft palate raised; air from lungs causes audible friction as it passes through the open glottis, and resonates through the vocal tract with a quality determined chiefly by the position of the tongue taken up for the following vowel; voiceless with some voicing when surrounded by vowels (aha).

AFFRICATES

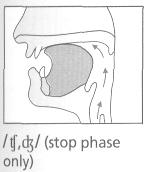

Articulation:

Palato-alveolar

affricates: soft palate raised;

for the first element, closure made by the tongue

tip, blade, and rims against the alveolar ridge and

side teeth; at the same time, front of the tongue is raised

towards the hard palate, so that when the closure

is released the air escapes to give a palato-alveolar

quality; //

voiceless, //

voiced; //

fortis, //

lenis; lip position influenced by following vowel (spread

for cheap,

rounded

for choose),

though some speakers

always round their lips for these sounds.

Articulation:

Palato-alveolar

affricates: soft palate raised;

for the first element, closure made by the tongue

tip, blade, and rims against the alveolar ridge and

side teeth; at the same time, front of the tongue is raised

towards the hard palate, so that when the closure

is released the air escapes to give a palato-alveolar

quality; //

voiceless, //

voiced; //

fortis, //

lenis; lip position influenced by following vowel (spread

for cheap,

rounded

for choose),

though some speakers

always round their lips for these sounds.

NASALS

Articulation:

Bilabial

nasal: soft palate lowered; a total

closure made by the upper and lower lip; voiced, with only occasional

devoicing (notably, after [s], as in smile);

labio-dental

closure when followed by /f/ or /v/,

as in comfort;

vowel-like

nature allows /m/ to be used

with a syllabic function, in such words as bottom

/btṃ/.

Articulation:

Bilabial

nasal: soft palate lowered; a total

closure made by the upper and lower lip; voiced, with only occasional

devoicing (notably, after [s], as in smile);

labio-dental

closure when followed by /f/ or /v/,

as in comfort;

vowel-like

nature allows /m/ to be used

with a syllabic function, in such words as bottom

/btṃ/.

Articulation:

Alveolar

nasal: soft palate lowered; closure

made by tongue tip and rims against the alveolar ridge and upper side

teeth; voiced, with only occasional

devoicing (notably, after [s], as in snap);

lip

position

influenced by adjacent vowel (spread in neat rounded in noon); much

affected by the place of articulation

of the following consonant (e.g. often labio-dental

closure when followed by /f/ or /v/ (as in infant),

bilabial

when followed by /p/ or /b/); vowel-like

nature allows /n/ to be used with a syllabic function

in such words as button

/b٨tṇ/.

Articulation:

Alveolar

nasal: soft palate lowered; closure

made by tongue tip and rims against the alveolar ridge and upper side

teeth; voiced, with only occasional

devoicing (notably, after [s], as in snap);

lip

position

influenced by adjacent vowel (spread in neat rounded in noon); much

affected by the place of articulation

of the following consonant (e.g. often labio-dental

closure when followed by /f/ or /v/ (as in infant),

bilabial

when followed by /p/ or /b/); vowel-like

nature allows /n/ to be used with a syllabic function

in such words as button

/b٨tṇ/.

Articulation:

Velar

nasal: soft palate lowered; voiced; closure formed between the back

of the tongue a nd

the

soft palate; further forward if preceded by front vowel

(sing,

compared

with bang);

lip

position depends

on preceding vowel (spread in sing,

rounded

in

song);

this is the normal nasal sound before /k/ or /g/

in such words as

sink and

angry,

despite

having only

an n

in the spelling.

nd

the

soft palate; further forward if preceded by front vowel

(sing,

compared

with bang);

lip

position depends

on preceding vowel (spread in sing,

rounded

in

song);

this is the normal nasal sound before /k/ or /g/

in such words as

sink and

angry,

despite

having only

an n

in the spelling.

ORAL CONTINUANTS

Articulation:

Lateral:

soft palate raised; closure made by

tongue tip against centre of alveolar ridge, and air escapes

round either or both sides; voiced, with devoicing chiefly after

fortis consonants (as in please,

sleep);

front

of tongue simultaneously raised in direction

of hard palate, giving a front-vowel resonance

in such words as RP

leap ('clear

I'); back of tongue

raised in direction of soft palate, giving a back vowel

resonance in such words as RP pool

('dark

I'); lip position

depends on adjacent vowel (spread in leap,

peel,

rounded

in loop,

pool);

vowel-like

nature allows /I/

to be used with a syllabic function in such words as bottle

/botḷ/.

Articulation:

Lateral:

soft palate raised; closure made by

tongue tip against centre of alveolar ridge, and air escapes

round either or both sides; voiced, with devoicing chiefly after

fortis consonants (as in please,

sleep);

front

of tongue simultaneously raised in direction

of hard palate, giving a front-vowel resonance

in such words as RP

leap ('clear

I'); back of tongue

raised in direction of soft palate, giving a back vowel

resonance in such words as RP pool

('dark

I'); lip position

depends on adjacent vowel (spread in leap,

peel,

rounded

in loop,

pool);

vowel-like

nature allows /I/

to be used with a syllabic function in such words as bottle

/botḷ/.

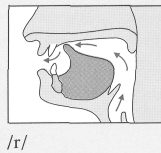

Articulation:

Post-alveolar

approximant (or frictionless

continuant): soft palate raised; tongue tip held

close to (but not touching) the back of the alveolar

ridge; back rims touch the upper molars; central

part of tongue lowered; lip position influenced

by following vowel (spread in reach,

rounded

in room);

becomes

a fricative when preceded by /d/ (as in drive);

becomes

a tap between vowels and after

some consonants (as in very,

sorry, three);

voiced,

with

devoicing after /p/, /t/, /k/ (as in pry);

lip

position influenced

by following vowel (spread in reed,

rounded

in rude),

but some speakers always give /r/ some

rounding.

Articulation:

Post-alveolar

approximant (or frictionless

continuant): soft palate raised; tongue tip held

close to (but not touching) the back of the alveolar

ridge; back rims touch the upper molars; central

part of tongue lowered; lip position influenced

by following vowel (spread in reach,

rounded

in room);

becomes

a fricative when preceded by /d/ (as in drive);

becomes

a tap between vowels and after

some consonants (as in very,

sorry, three);

voiced,

with

devoicing after /p/, /t/, /k/ (as in pry);

lip

position influenced

by following vowel (spread in reed,

rounded

in rude),

but some speakers always give /r/ some

rounding.

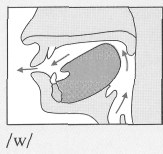

Articulation:

Labio-velar

semi-vowel: soft palate raised;

tongue in the position of a close back vowel; lips

rounded, with greater tension than for [u:] (compare

woos

and ooze);

voiced, with some devoicing

after fortis consonants (twice,

sweet).

Articulation:

Labio-velar

semi-vowel: soft palate raised;

tongue in the position of a close back vowel; lips

rounded, with greater tension than for [u:] (compare

woos

and ooze);

voiced, with some devoicing

after fortis consonants (twice,

sweet).

Articulation:

Palatal

semi-vowel; soft palate raised; tongue in the position of a front

close vowel; lip position influenced by following vowel (spread in

year,

rounded in you);

greater tension than for [i:] (compare

yeast

and east);

voiced, with some devoicing after

fortis consonants (pure,

huge).

Articulation:

Palatal

semi-vowel; soft palate raised; tongue in the position of a front

close vowel; lip position influenced by following vowel (spread in

year,

rounded in you);

greater tension than for [i:] (compare

yeast

and east);

voiced, with some devoicing after

fortis consonants (pure,

huge).

ARTICULATORY TRANSITIONS OF VOWELS AND CONSONANT PHONEMES.

In the process of speech, i.e. in the process of transition from the articulatory work of one sound to the articulatory work of the neighbouring one, sounds are modified. The adaptation of the articulatory work of the two neighbouring sounds may result in assimilation. Assimilation may be not only contact, but also distant, when distant sounds are affected. On the phonetical level the sounds modified in the process of assimilation are analyzed as positional variants of vowel and consonant phonemes.

Assimilation may be:

living historical

(occurs in everyday speech) (the results of it can be traced on the

diachronical level:

e.g.:

permission [p∂r’misj∂n]; measure

e.g.:

permission [p∂r’misj∂n]; measure

partial complete [‘mezjur]. In the course of time [sj, zj]

(is ch – zed by partial (is ch – zed by complete turned into [∫ - z]

similarity of one sound similarity of the 2 sounds

to the other. It is sub - e.g.: cupboard [‘kΛb∂d]

divided into:

progressive regressive reciprocal

(when the 1st sound (when the assimilated (when both sounds

affected by assimilation sound precedes the are equally affected

makes the 2nd sound conditioning sound: by assimilation:

similar to itself: e.g.: in the e.g.: twice

e.g.: desks, pens

Cases of assimilation:

the assimilation of a consonant to the following round vowel and the sonorant [w]:

nasalization – all Eng. vowels are oral (they are produced with the raised soft palate). But if the soft palate is lowered at the medial stage of the nasal sonorants followed by a vowel, the air escapes through the nasal cavity, making the vowel nasal:

nasal position (a plosive + a nasal sonorant) affects the manner of noise production:

acc. to the active organ of speech:

sounds [t – d, s – z, n, l] become interdental before interdental [θ, δ]:

e.g.: eighth, breadth, pass the salt, fill the gap, runs the theatre, in the;

bilabial [m] and apical alveolar [n] become labio – dental before [f – v]:

e.g.: comfort, infant, in vain, give them violets;

sounds [t – d] before post – alveolar [r] become post - alveolar:

e.g.: try, dry;

acc. to the work of the vocal cords:

- sonorants [m, n, l, w, j, r, ή] are partially devoiced when preceded by a voiceless consonant:

e.g.: drink milk, snake, at last, sweep stupid, try;

- verbs “is, has” in contracted forms after a voiceless consonant are partly devoiced:

e.g.: it’s, Pete’s;

the pronunciation of the possessive case and the plural ending of the nouns, the ending of the past tense and past participles:

e.g.: Kate’s cat, picked, cats;

- there is a nasal plosion (a plosive + a nasal) or a lateral plosion (a plosive + a lateral):

e.g.: mutton, garden, little, model;

- lose of plosion when 2 plosives meet each other:

e.g.: ask Dick;

acc. to the position of the lips all sounds become labialised before labial [w]:

e.g.: twinkle

acc. to the position of the soft palate:

e.g.: handsome [‘hænds∂m, hænns∂m, hæns∂m].

MODIFICATION OF CONSONANTS AND VOWELS IN CONNECTED SPEECH.

Lge in everyday use is not conducted in terms of isolated, separate units; it is performed in connected sequences or larger units, in words, phrases and longer utterances. There are some differences in pronunciation of a word in isolation and of the same word in a block of connected speech. These changes are mostly quite regular and predictable. Still the problem of defining the phonemic status of sounds in connected speech is by far too complicated because of the numerous modifications of sounds in speech. These modifications are observed both within words and at word boundaries. Speech sounds influence each other in the flow of speech. As a result of the intercourse between consonants and vowels and within each class there appear such processes of connected speech as assimilation, accommodation, vowel reduction and elision (sometimes defined as deletion).

The adaptive modification of a consonant by a neighbouring consonant in the speech chain is known as assimilation.

Consonants are modified acc. to the place of articulation. Assimilation takes place when a sound changes its character in order to become more like a neighbouring sound. The characteristic, which can vary in this way is nearly always the place of articulation, and the sounds concerned are commonly those, which involve a complete closure at some point in the mouth, i.e. plosives and nasals may be illustrated as follows:

the dental [t, d], followed by the interdental [θ, δ] sounds (partial regressive assimilation when the influence goes backwards from a “latter” sound to an “earlier” one);

the apical alveolar [t, d] under the influence of the post – alveolar [r] (partial regressive assimilation);

the apical alveolar [s, z] before [∫] (complete regressive assimilation: horse – shoe [‘ho:∫∫u:]);

the affricative [t+j, d=j] combinations (incomplete regressive assimilation: did you [‘didzju:], could you [kudzju:]).

The place of articulation of nasals also varies acc. to the place of articulation:

the bilabial [m] becomes labio – dental followed by the labio – dental [f, v] (e.g.: symphony);

the apical alveolar [n] becomes interdental before [θ, δ];

the apical alveolar [n] becomes palato – alveolar corresponding to the following affricate (e.g.: pinch);

[n] assimilated to the velar consonant [k] becomes velar [ή] (e.g.: thank). The same occurs across syllable boundaries, across morpheme boundaries, in prefixes in-, un-.

The manner of articulation is also changes as a result of assimilation:

loss of plosion: in sequences of 2 plosives the former loses its plosion (partial regressive assimilation);

nasal plosion: in the sequence of a plosive followed by a nasal sonorant the manner of articulation of the plosive sound and the work of the soft palate are involved, which results in the nasal ch – er of plosion released (partial regressive assimilation);

lateral plosion: in the sequence of a plosive followed by a lateral sonorant the noise production of the plosive is changed in to the lateral stop (partial regressive assimilation).

The voicing value of a consonant may also change through assimilation. This type of assimilation affects the work of the vocal cords and the force of articulation. In particular voiced lenis sounds become voiced fortis when followed by another voiceless sound:

fortis voiceless/ lenis voiced type of assimilation is best manifested by the regressive assimilation in such words as “newspaper (news [z] + paper); gooseberry (goose [s] + berry). In casual informal speech voicing assimilation is often met (e.g.: have to do it [‘hæf t∂ ‘du: it], five past two [‘faif pa:st ‘tu:]. The sounds, which assimilate their voicing, are usually voiced lenis fricatives assimilated to the initial voiceless fortis consonants of the following words. Grammatical items are also affected (e.g.: [z] in “has, is, does” changes to [s], and [v] of “have, of” becomes [f]);

the weak forms of the verbs “is” and “has” are also assimilated to the final voiceless fortis consonants of the preceding word thus the assimilation is functioning in the progressive direction (e.g.: your aunt’s coming);

Eng. sonorants [m, n, r, l, j, w] preceded by the fortis voiceless consonants [p, t, k, s] are partially devoiced (partial progressive assimilation).

The term accommodation is used to denote the interchange of “vowel + consonant type” or “consonant + vowel type” (e.g.: some slight degree of nasalization of vowels preceded or followed by nasal sonorants: ball, pull).

Lip position may be affected by accommodation, the interchange of consonant + vowel type. Labialisation of consonants is traced under the influence of the neighbouring back vowels (e.g.: pool, moon, soon, cool, who). It is possible to speak about the spread lip position of consonants followed or preceded by front vowels [I:, I] (e.g.: tea – beat, meet – team; feat – leaf).

The position of the soft palate is also involved in the accommodation. Slight nasalization as the result of prolonged lowering of the soft palate is sometimes traced under the influence of the neighbouring sonorants [m, n] (e.g.: and, morning, men, come in).

Elision or complete loss of sounds, both vowels and consonants, is often observed in Eng. Elision is likely to be minimal in slow careful speech and maximal in rapid relaxed colloquial forms of speech. it is typical of rapid colloquial speech and marks the following sounds;

loss of [h] in personal and possessive pronouns and in the forms of the auxiliary verb “have”;

[l] tends to be lost when preceded by [o:] (e.g.: always [‘o:wiz]);

alveolar plosives are often elided in case the cluster is followed by another consonant (e.g.: next day [‘neks ‘dei]). If a vowel follows, the consonant remains (e.g.: first of all).

Examples of historical elision are also known. They are initial consonants in “write, know, knight”, the medial consonant [t] in “fasten, listen, whistle, castle”.

While the elision is a very common process in connected speech, we also occasionally find sounds being inserted. When a word which ends in a vowel is followed by another word beginning with a vowel, the so – called intrusive [r] is sometimes pronounced between the vowels (e.g.: Asia [r] and Africa, the idea [r] of it, ma [r] and pa). The so – called linking “r” is a common example of insertion (e.g.: clearer, a teacher of Eng.). When the word final vowel is a diphthong, which glides to [I] such as [ai, ei] the palatal sonorant [j] tends to be inserted (e.g.: saying [‘seijiή]). In case of the [u] – gliding diphthongs [ou, au] the bilabial sonorant [w] is inserted (e.g.: going [‘goiwiή]).

One of the wide – spread sound changes is vowel reduction. Reduction is quantitative or qualitative weakness of vowels in unstressed positions (e.g.: board – black board; man – postman). Reduction is one of the factors that condition the defining of the phonemic status of vowel sounds in a flow of speech. the modification of vowels in a speech chain are traced in the following directions: they are either quantitative or qualitative or both. These changes of vowels in a speech continuum are determined by a number of factors such as the position of the vowel in the word, accentual structure, tempo of speech, rhythm.

The decrease of the vowel quantity or in other words the shortening of the vowel length is known as a quantitative modification of vowels, which may be illustrated as following:

the shortening of the vowel length occurs in unstressed positions (e.g.: blackboard [o:], sorrow [ou] = reduction). In these cases reduction affects both length of the unstressed vowel and its quality.;

the length of a vowel depends on its position in a word. It varies in different phonetic environments. Eng. vowels are said to have positional length (e.g.: knee – need – neat (accomodation)). The vowel [I:] is the longest in the final position, it is shorter before the lenis voiced consonant [d], and it is the shortest before the fortis voiceless consonant [t]. Qualitative modification of most vowels occurs in unstressed positions.

Unstressed vowels lose their quality:

in unstressed syllables vowels of full value are usually subjected to qualitative changes (e.g.: man [mæn] – sportsman [‘spo:tsm∂n). in such cases the quality of the vowel is reduced to the neutral sound [∂] = the neutralization. The neutral sound [∂] is the most frequent sound of Eng. a high frequency of [∂] is the result of the rhythmic pattern: if unstressed syllables are given only a short duration, the vowel in them, which might be otherwise full, is reduced. It is common knowledge that Eng. rhythm prefers a pattern, in which stressed syllables alternate with unstressed ones. The effect can be seen even in single words, where a shift of stress is often accompanied by a change of vowel quality; a full vowel becomes [∂] and [∂] becomes a full vowel (e.g.: analyze ‘æn∂laiz] – analysis [∂’nælisis]); in both words full vowels appear in the stressed positions, alternating with [∂] in a stressed syllable, and almost as impossible to have a full vowel in every unstressed syllable.

Slight degree of nasalization marks vowels preceded or followed by the nasal consonants [n, m] (e.g.: never, no, then, men). The realization.

The realization of reduction is connected with the style of speech. in rapid colloquial speech it may result in vowel elision, the complete omission of the unstressed vowel, which is also known as zero reduction. Zero reduction is likely to occur in a sequence of unstressed syllables (e.g.: history, factory, literature). It often occurs in initial unstressed syllables preceding the stressed one (e.g.: correct, believe, suppose).

SYLLABLE.

A syllable is a speech unit higher than a sound, because sounds are not pronounced separately but are usually formed into syllables, which, in their turn, are joined into words, phrases and sentences. A syllable is the minimal unit of sounding speech.

The syllable can be analyzed from acoustic, articulatory and functional points of view. It can also be viewed in connection with its graphic representation:

acoustically a syllable is characterized by the force of utterance, or accent, pitch of the voice, sonority and length (“ˉ “, “˘ “), that is by prosodic features.

articulatory characteristics of a syllable are connected with sound juncture and with the theories of syllable formation and syllable division;

functional, or phonemic, characteristics of a syllable are connected with the constitutive, recognitive and distinctive properties of a syllable;

syllables in writing are called syllabographs and are closely connected with the morphemic structure of a word.

A syllable can be formed by a vowel (V), by a vowel and a consonant (VC), by a consonant and a sonorant (CS) (such structures characterizes only the English syllabic system). There are 4 types of syllables in English:

V type : fully open;

CVC type: fully closed;

CV type: initially covered;

VC: finally covered.

Type |

example |

type |

example |

V CVC CVCC CVCCC CCVC CCCVC CCVCC CCVCCC |

err pit fact lapsed plan spleen twiddle stamps |

CCCVCC CVCCCC VCVCCCC CV CCV CCCV VC VCC VCCC |

spleens texts attempts dew spy straw eat act asks |

The English sonorants can form syllables with consonants preceding them. The structural patterns of syllables formed by sonorants with a preceding consonant in English are similar to V+C pattern:

CS written [‘ritn]

CVCS license [‘lais∂ns]

CCVCS sanctions [‘sæŋk∫∂nz]

CVSCC scaffolds [‘skæf∂ldz]

CSVSCC entrants [‘entr∂nts]

THEORIES OF SYLLABLE FORMATION AND SYLLABLE DIVISION.

There are different points of view on syllable formation, which are the following:

the most ancient theory states that there are as many syllables in a word as there are vowels. This theory is primitive and insufficient, since it doesn’t take in consideration consonants, which also can form syllables in some lges, neither does it explain the boundary of syllables;

the expiratory theory states that there are as many syllables in a word as there are expiration pulses. According to it the borderline between the syllables is the moment of the weakest expiration. But it is inconsistent because it’s quite possible to pronounce several syllables in one expiration;

the sonority theory states that there are as many syllables in a word as there are peaks of prominence according to the scale of sonority:

v

owels

owels

s onorants

onorants

v oiced constrictive

voiced plosive

v oiceless

constr.

oiceless

constr.

voiceless plosive

sudden star

the “arc of loudness” theory is based on Shcherba’s statement that the centre of a syllable is the syllable forming phoneme. Sounds, which precede or follow it constitute a chain or an arc, which is weak in the beginning and in the end and strong in the middle. If a syllable consists of one vowel, then its strength increases in the beginning, reaches the maximum of loudness and then gradually decreases.

a

a

a a

According to it consonants in the structural patter can be viewed as 1) initially weak, 2) finally weak, 3) initially strong, 4) finally strong, 5) double peaked (combination of two similar sounds)

I ei

m

s t k

m

s t k

GRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF SYLLABLES.

The auditory image of a syllable can be shown in transcription. But parts of orthography and phonetic system do not always coincide:

e.g.: ta – ble [‘tei – bl], po – et [‘pзu – it]

It’ s very important to observe correct syllable division when necessity arises to divide a word in writing. Division of words into syllables in writing is based on morphological principles, which demand that the part of word separated should be either a prefix, or a suffix, or a root:

e.g.: un – divided, smil – ing

However, there are some cases to follow in syllable division:

if there are 2 or 3 consonants before –ing, they may be separated: grasp – ing, puz – zling.

the suffix –ed can be separated only if it is preceded by “t/d”: divid – ed, decid – ed.

polygraphs are not separated: dial, ancient.

2 or more consonants before a suffix that begins with a vowel may be separated: big – ger, gras – ping.

The single intervocal consonant between 2 phonetic syllables belongs to the next vowel: cosy [‘kзu – zi], muddy [‘m۸ – di]