- •I.1 Preliminary Remarks

- •I.2 Cases of Consciousness (or Its Absence)

- •I.3 Kinds of Consciousness

- •I.4 Kinds of Unity

- •Figure I.2

- •1.1 Multiple Experiences and the Problem of Unity

- •1.2 Undermining the Problem as Standardly Conceived

- •1.3 The One Experience View

- •1.4 An Account of Synchronic Phenomenal Unity

- •Figure 1.1

- •2.1 The Body Image

- •2.2 A Theory of Bodily Sensations

- •2.3 The Problem of Bodily Unity

- •3.1 Opening Remarks

- •3.2 Perceptual Consciousness and Experience of the Body

- •3.3 Unity and Conscious Thoughts

- •3.4 Unity and Felt Moods

- •4.1 Examples of Unity through Time

- •4.2 The Specious Present and the Problem of Diachronic Unity

- •4.3 An Account of Unity through Time

- •4.4 Some Mistakes, Historical and Contemporary

- •4.5 Carnap and the Stream of Consciousness

- •5.1 Results of Splitting the Brain

- •Figure 5.1

- •5.2 Multiple Personality Disorder, Split Brains, and Unconscious Automata

- •5.3 Indeterminacy in the Number of Persons

- •5.4 Disunified Access Consciousness

- •5.5 Disunified Phenomenal Consciousness: Two Alternatives

- •5.6 The Nontransitivity of Phenomenal Unity

- •6.1 The Ego Theory and the Bundle Theory Quickly Summarized

- •6.2 Objections to the Ego Theory

- •6.3 Objections to the Bundle Theory

- •6.4 A New Proposal

- •6.5 Problem cases

- •6.6 Vagueness in Personal Identity

- •Introduction

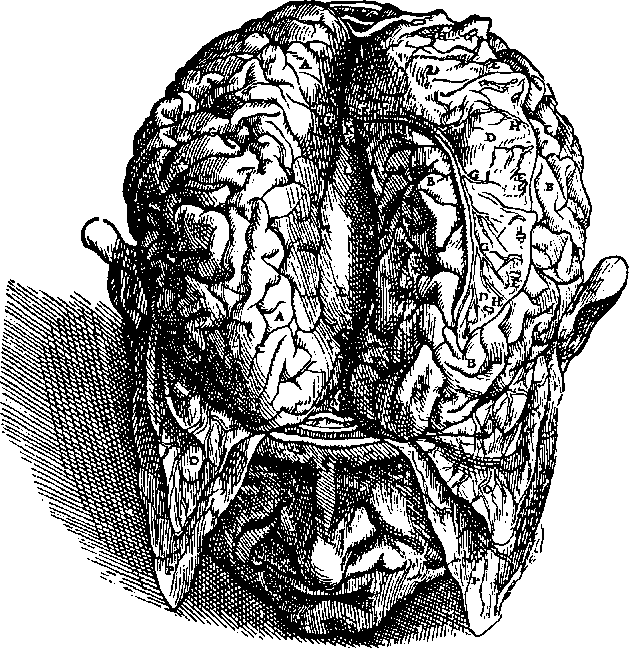

5.1 Results of Splitting the Brain

The human brain is divided into two more or less symmetrical hemispheres. The surgical removal of one of these hemispheres does not eliminate consciousness, and neither does cutting the many connections of the corpus callosum between the hemispheres. The latter operation, originally performed by Roger Sperry in the 1960s on some epileptic patients with the aim of controlling epileptic seizures, has a remarkable consequence. In addition to reducing greatly the number and intensity of the seizures themselves, it also produces a kind of mental bifurcation in the epileptic patients.

5

Here is an illustration. A subject, S, is told to stare fixedly at the center of a translucent screen that fills his visual field. Two words are flashed onto the screen by means of a projector located behind, one to the left of the fixation point and one to the right, for example, the words 'pen' and 'knife'. The words are flashed very quickly (for just 1/10 of second) so that eye movements from one word to the other are not possible. This arrangement is one that ensures that the word on the left provides input only to the

The

two hemispheres divided.

Figure 5.1

right hemisphere of the brain and the word on the right provides input only to the left.

S is then asked what he saw. S shows no awareness, in his verbal responses, of 'pen'. However, if S is asked to retrieve the object corresponding to the word he saw from a group of objects concealed from sight, using his left hand alone, he will pick out a pen while rejecting knives. Alternatively, if S is asked to point with his left hand to the object corresponding to the word he saw, he will point to a pen. Moreover, if S is asked to sort through the group of objects using both hands, he will pick out a pen with his left and a knife with his right. In this case, the two hands work independently with the left rejecting the knives in the group and the right rejecting the pens.

Interestingly, split-brain subjects, when first asked to use the left hand to identify objects out of sight by touch from among a group of such objects, commonly say that they "cannot work with that hand" or that it "is numb." After they successfully identify a series of objects and are asked how they could have done this if they are unable to feel the objects, they say things like "Well, I was just guessing" or "Well, I must have done it unconsciously" (Sperry 1968).

There is much more data, some of it fascinating. For example, a smell presented to the right nostril will lead the split-brain subject to deny verbally that there is any smell; but if asked to point with his left hand at the object with the smell, he will pick out a clove of garlic, while continuing to deny that there is a smell and insisting verbally that he thus cannot point to what smells. In another experiment (noted in Nagel 1971), the subject is told to hold an object in his left hand, a pipe, say, out of sight and to write down afterward with his left hand what he was holding. The subject slowly starts to write 'P' followed by 'I'. Then the writing speed increases, with the subject changing the 'I' to an 'E' and the word being completed as 'PENCIL'. Here, it seems, the verbal left hemisphere has taken control and made a guess as to the appropriate word, based on the appearance of the first two letters. Then the right hemisphere regains control, with the word 'pencil' being deleted and a picture of a pipe being crudely drawn in its place.

What are we to make of these results? It has been variously suggested (a) that split-brain subjects are really two

persons with two separate minds; (b) that the responses produced by the right hemisphere are those of an unconscious automaton; (c) that it is indeterminate how many persons split-brain subjects are and that the concept of a person is thrown into jeopardy by the experimental results; (d) that split-brain subjects have a unified phenomenal consciousness but a disunified access consciousness; (e) that split- brain subjects are single persons who undergo two separate streams of consciousness that remain two from the time of the commissurotomy; (f) that split-brain subjects are single persons whose phenomenal consciousness is briefly split into two under certain special experimental conditions, but whose consciousness at other times is unified.

The most plausible view, I shall argue, is (f). I shall also argue that the best explanation of certain experimental results for split-brain subjects requires that the phenomenal unity relation be nontransitive. This, as we shall see, offers further support for the account of unity I have been defending.