- •I.1 Preliminary Remarks

- •I.2 Cases of Consciousness (or Its Absence)

- •I.3 Kinds of Consciousness

- •I.4 Kinds of Unity

- •Figure I.2

- •1.1 Multiple Experiences and the Problem of Unity

- •1.2 Undermining the Problem as Standardly Conceived

- •1.3 The One Experience View

- •1.4 An Account of Synchronic Phenomenal Unity

- •Figure 1.1

- •2.1 The Body Image

- •2.2 A Theory of Bodily Sensations

- •2.3 The Problem of Bodily Unity

- •3.1 Opening Remarks

- •3.2 Perceptual Consciousness and Experience of the Body

- •3.3 Unity and Conscious Thoughts

- •3.4 Unity and Felt Moods

- •4.1 Examples of Unity through Time

- •4.2 The Specious Present and the Problem of Diachronic Unity

- •4.3 An Account of Unity through Time

- •4.4 Some Mistakes, Historical and Contemporary

- •4.5 Carnap and the Stream of Consciousness

- •5.1 Results of Splitting the Brain

- •Figure 5.1

- •5.2 Multiple Personality Disorder, Split Brains, and Unconscious Automata

- •5.3 Indeterminacy in the Number of Persons

- •5.4 Disunified Access Consciousness

- •5.5 Disunified Phenomenal Consciousness: Two Alternatives

- •5.6 The Nontransitivity of Phenomenal Unity

- •6.1 The Ego Theory and the Bundle Theory Quickly Summarized

- •6.2 Objections to the Ego Theory

- •6.3 Objections to the Bundle Theory

- •6.4 A New Proposal

- •6.5 Problem cases

- •6.6 Vagueness in Personal Identity

- •Introduction

3.1 Opening Remarks

So far, I have discussed the unity of perceptual experience and the unity of bodily experience at a time. But I have not addressed their common unity. The experienced qualities of smells, sounds, tastes, and so on are not unified in isolation from what is felt in the body. If, for example, I feel a pain in a finger I am examining, pain is experienced together with the qualities I experience perceptually. The finger is presented to me visually and tactually while I feel pain in it; and all these elements are unified or connected in my consciousness.

There is unity too with occurrent thoughts and moods. The pain in my finger is one that has been there for some time. It is not responding to treatment. As I examine it, I feel mildly depressed. I think to myself that I can't type with that finger, that I have writing I must get done in the next few days, and that I am already way behind. I begin to worry. The pain intensifies. I rub my finger harder.

The train of thinking I undergo here is a conscious one. It involves several occurrent thoughts, the qualities of which are unified with the experienced qualities of the depression I feel and the pain I experience.

I argued in chapter 1 that in normal, everyday cases, people do not undergo five different simultaneous perceptual experiences as they use all five senses. Rather they undergo a single perceptual experience at a given time, an experience with a visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, and tactual phenomenology. In chapter 2, I took a corresponding view for bodily experience. What should we say about perceptual-bodily unity? That is the topic of section 3.2 of this chapter. Section 3.3 addresses the unity of experiences with conscious thoughts. Section 3.4 focuses on moods.

3.2 Perceptual Consciousness and Experience of the Body

In the last chapter, I argued that bodily experience is an experience that represents the body space and boundaries, along with various internal bodily disturbances. The experience of the body is also part and parcel of normal, everyday perceptual consciousness. For we experience things in relation to our bodies. And this involves experience of our bodies.

In the case of touch and taste, this is obvious. We taste things with our tongues, and the experience of them involves contact with our tongues and mouths, which is itself part of the phenomenology. Likewise, we touch things with our hands and we experience the contact with the things touched. One who lacks any feeling in her mouth, tongue, and fingers cannot experience the soft, smoothness of a velvet tunic against her fingers or the taste of gin as it runs over her tongue and down her throat.

This is not to imply that an abnormal subject without any feeling in her fingers could not acquire the knowledge by touch that her fingers are touching the velvet or that the velvet is smooth. Still, such a subject lacking any feeling of where her fingers are would not experience the contact between her fingers and the velvet. Thus, her awareness by touch would be very different from ours.

Recall the case of Madame I in chapter 2, the woman who had lost her body image. She reported that she could not feel arms, leg, head, and hair, adding "I have to touch myself constantly to know how I am" (Rosenfield 1992, p. 39). Touch informed Madame I of where her body was, but she could not feel the location of her body, and so she could not feel the contact between her fingers, as she ran them across her body, and the part of her body she was touching.

I also do not mean to suggest that real fingers are necessary in order for a person to have the experience of touching something with her fingers. If my right hand has been amputated, I may still feel fingers there, and if I do, I may undergo an experience that represents the presence of a surface in contact with my fingers. What is crucial to the experience of contact is that the part be represented in the person's body image.

Smells and sounds are experienced as occupying spatial locations and coming from directions. The loud noise of the firecracker is experienced as being on the left; the fragrant smell of the flower is experienced as being where the flower is, a little to the right, say. The directions left and right here are set by the body of the perceiver. Interestingly, it is the torso that seems to be most important. A noise from behind on the left is normally experienced in that location even if one's head is rotated backward to the left, while keeping the torso motionless, so that the sound is in front of the rotated ear. Similarly a smell from the right side in front is still experienced as being on the right, if one turns one's head so that one's nose is aligned with the smell.

I am not claiming that an experience of the body is required in every case for an experience of a sound in a given direction. What an experience of the latter type requires is an experience of here; a sound to the left, for example, just is a sound to the left of here. In the normal case, the experience of here is the experience of a certain bodily location that is the origin for up/down, back/front, and left/right axes whose directions are set by the torso. But arguably, one could still undergo auditory experiences as coming from definite directions even if one's body was completely anaesthetized. I shall return to this point shortly.

Consider vision. Tilt your head from left to right, as you sit viewing a painting on a wall, while keeping your body upright. The painting does not seem to tilt with the head. The bottom of the painting still appears horizontal, and the sides upright.1 Nor does the painting seem to tilt if you keep your head position fixed relative to the torso, while tilting the torso forty-five degrees to the right.2 Now rotate your torso forty-five degrees to the right and rotate your head back to its original position so that the painting is level with the eyes. The painting will be experienced as being off to the side from the direction of straight ahead.

In experiencing things visually, we experience their orientations and directions, and these are set in part by our own bodies. We use our own bodies to assign orientations and directions to things, as manifested in the visual phenomenology. The spatial properties of being horizontal and being upright, for example, are relative to a set of axes, positioned at the viewer. Intuitively, these axes have their origin centered between the viewer's eyes. Their directions, however, are not up/down, left/right, back/front with respect to the head; if they were, the painting would appear to shift its orientation as the head is moved.3 Instead the axes have their back/front and left/right directions set relative to the torso in the usual way, with the up/down direction usually set via the directional pull of gravity on the torso.

Again, I am not supposing that experience of the body is required for visual experience. The point is that in experiencing the direction or orientation of something, we experience it as being in a certain direction or at a certain orientation relative to a certain viewpoint. That viewpoint is one we experience ourselves as occupying; and in normal vision, we experience that viewpoint as being within our bodies—intuitively, somewhere in the middle of our heads behind the eyes. Even so, the torso, not the head, is the most important bodily factor in fixing how the directions of the axes are for that viewpoint.

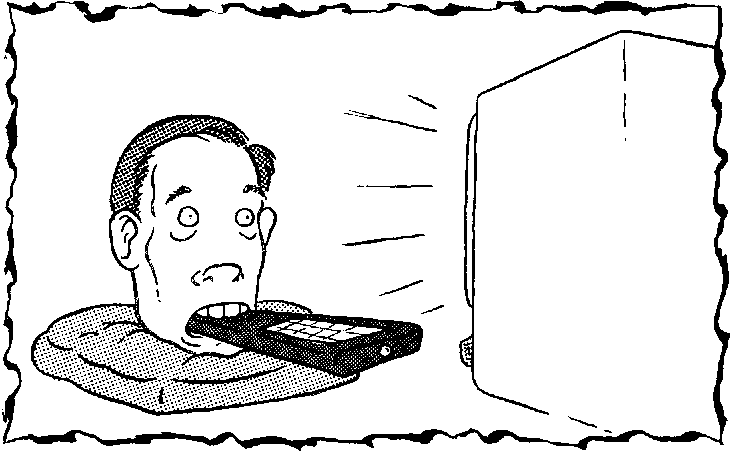

That the relevant viewpoint is in the head behind the eyes is well illustrated by the following story adapted from Dennett (1978). Suppose that neurosurgery has developed to the point at which it is possible to remove brains from bodies, while replacing the severed nerves with two-way radio connections that allow the brains and bodies to communicate just as they did before. The connections are established via tiny radio transceivers attached to the severed nerve endings. One morning I awaken, knowing that this operation was performed on me last night, and I feel just as I did before. Upon looking in a mirror, I see the same face I always did and, looking down, my body appears just the same. I then ask to see my brain and I am taken to a vat, full of fluid, in which my brain is floating, surrounded by electronic gadgetry. As I view the brain, I think to myself, "Here I am, looking at my own brain. The world is certainly a weird and wonderful place." I am a physicalist, however. And I believe that my experiences take place in my brain. Why, then, didn't I think, "Here I am, in a vat of fluid, being stared at by my own eyes"?

(13) The answer surely is that my visual experience of the world is an experience of things in relation to a certain viewpoint, and that viewpoint is one I locate behind where I feel my eyes to be within where I feel my head. My experience in the above case is of my brain in front of me; it is not an experience of my own eyes straight ahead, turned in my direction— as would be the case if I were normally embodied but my eyes had been removed and rotated toward my body while keeping their connections to my head intact (by applying a special chemical stretching agent to those connections, say). I naturally think that my brain is in front of me because I naturally and normally locate my viewpoint behind where my eyes feel to be within my head (quite correctly until this morning).

Still, why is it that my thought that I am here, looking at my own brain, persists even after my physicalist reflections should lead me to locate myself where my brain is? The explanation, I suggest, is that my thought, like all conscious thoughts, comes wrapped in an auditory linguistic image. It is for me as if I am speaking words internally in my natural language in my characteristic pattern of stress and intonation. In consciously thinking, thus, I undergo an associated auditory experience and the sounds represented by that experience are experienced as sounds made by me and

further as sounds I am making within where my head is experienced to be. Accordingly, the phenomenology of my conscious thoughts places me outside my brain, behind my eyes; and that is what makes it so hard for me to think that I am really where my brain is, rather than being in front of it.

(14) My claim that experience of the body is not required for visual experience or for auditory experience is supported by the case of Madame I. She seems to have had roughly normal vision, with some reduction in visual acuity for distance, and normal hearing, but she had no body image.

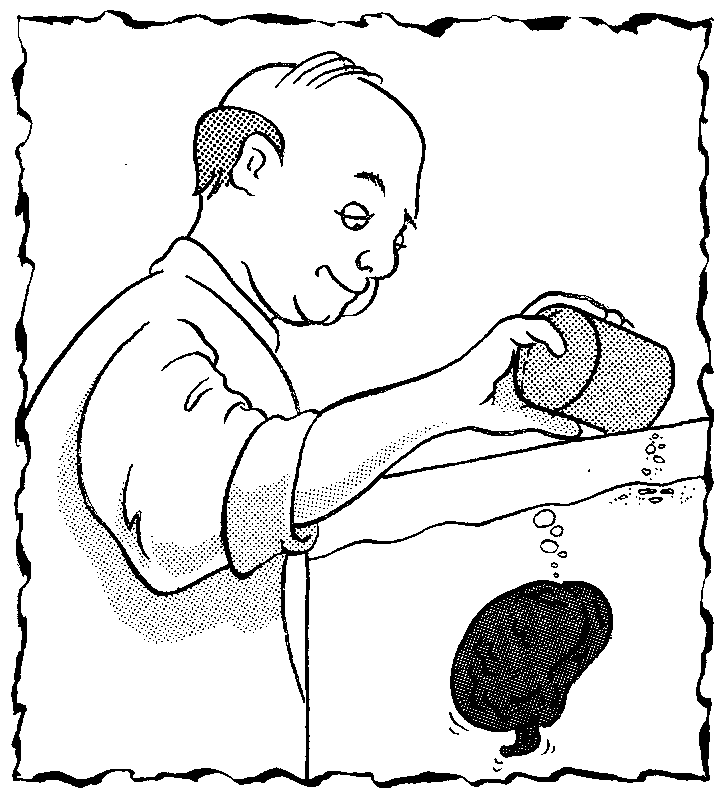

Consider also the following imaginary case.4 Suppose that while you are sleeping one night, a complex and fiendish operation is performed by mad scientists in which your brain is removed from your body, and then, after brain removal, your head is severed and the rest of your body destroyed. The severed head is supplied artificially with blood from a machine and its auditory and visual receptors have radio transceivers attached to them. Radio transceivers are also attached to the auditory and visual nerve endings dangling from the disembodied brain. The transceivers connected to your head are tuned so that they will receive radio messages from the corresponding transceivers attached to your brain, as soon as a switch is flipped. Your head is now placed on a chair, right side up, in front of a TV set with your favorite episode of Monty Python playing. The switch is flipped.

Would you suddenly go from experiencing nothing to having visual and auditory experiences of Monty Python? Would you hear the words, "And now for something completely different," as John Cleese speaks them? Would you see and hear Michael Palin, as he performs the Lumberjack Song? It seems to me that you would. All the relevant information is getting passed from your eyes and ears to your brain; the same neural regions in the visual and auditory cortexes are being activated in just the way they would have been activated, had you been sitting and watching Monty Python in the usual way. But you would have no experience of your body; for your body other than your head has been destroyed and the only links between your brain and your head are the auditory/visual ones. Admittedly, you might go mad pretty quickly, or you might develop a strong

aversion to Monty Python. But the case, though fantastic, is surely coherent. And its coherence shows that it is possible for a subject to undergo auditory and visual experiences while having no bodily experience whatsoever.

(15) At the current time, sitting on a patio by a swimming pool with my computer while sipping some tea, I have a single perceptual experience with a rich and multimodal phenomenology. My experience represents to me visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, and tactual features in relation to myself. I experience the red flowers to the left of here, the diamond shape of the tiles on the patio relative to me and my viewing position, the sounds of a bird straight ahead, the smell of the chlorine from the pool off to my right, the smoothness of the computer keys against my fingers, the taste of the tea as it comes into contact with my tongue. The world, as I perceptually experience it, thus, is a world in relationship to here. And here, in the normal case, is where my body or certain parts of my body feel to be.

At the current time, I also feel an itch from a mosquito bite on my ankle and a pain in my left knee from too much running. The pain is unified with the itch and they are both experienced together with the various things I experience perceptually. This is so, I now want to suggest, because I am undergoing but one experience at the current time, an experience of a perceptual-bodily sort. There is indeed a single perceptual experience; and there is a single bodily experience. But there is just one experience here, described in two different ways. This experience represents the sounds, smells, tastes, surfaces, and so on in the world around me in relation to my body, its parts and their boundaries, together with various bodily disturbances. My current experience is closed under conjunction across the board.5 And with such closure goes perceptual-bodily unity.

Without an experience of the body, there can be no experience of pain, no itches, no tickles. But perceptual experience can still remain; for, as we have seen, such experience can occur in the absence of bodily feeling. Even so, without the experience of the body, there is certainly no question of uniting bodily and perceptual experience and thus no problem to be considered concerning their unity.

Can there be cases in which both perceptual and bodily experience are present, but there is perceptual-bodily disunity? Here is one possible, imaginary candidate. Suppose that while you are sleeping one night you are given a drug to prevent you from waking and your eyes and your ears are removed from your head, while keeping their neural connections intact. This is accomplished via the application of a special neuron-stretching chemical agent that is applied to the relevant neurons as the eyes and ears are detached from your head. An anesthetic is injected into your head so that when you awaken you will have little or no bodily feeling in the head except for the mouth region. Next, your nose is sealed, and a mouthpiece, which is attached to an oxygen supply, is placed in your mouth. You are then placed, lying in a horizontal position, inside a large chamber of sand, with the exception of your eyes and ears, which are positioned above the sand in roughly their usual relative positions so that they can detect the sights and sounds you would have been able to detect had you been above the sand in your usual embodiment.

The sand in which you are buried is within an IMAX movie theater. There is no one else around. When you come to, you experience just the sights and sounds you would experience were you on a wild roller-coaster ride; for that is what is presented to you via the screen and the sound system in the theater. As far as your audiovisual experience goes, it is for you as if you are on a roller coaster. But that is not how it seems to you, as far as your bodily and tactual experiences are concerned. You feel the mouthpiece in your mouth, your body lying in the horizontal position, your rthyhmic but labored breathing, the pressure of the sand on your chest and legs—a pressure that keeps you motionless with the exception of your fingers as you straighten and close them in the sand. You have the bodily and tactual experiences of someone buried alive!

On the one hand, then, it seems to you that you are moving fast through space, up and down, round and round. On the other, it seems to you that you are trapped, motionless, underground. Is not this a case of perceptual-bodily disunity?

It seems to me unclear. To be sure, your overall experience is likely to seem incredible to you. Your auditory and visual experiences are completely at odds with the ones provided you by your sense of touch and the associated bodily sensations. With your introspective attention directed one way, you are aware that you are having an experience as of yourself on a roller coaster. With your attention directed differently, you are aware that you are having experiences that go with lying horizontally, surrounded by sand or loose dirt. It is, then, as if you are in two radically different worlds.6

Even so, it seems to me, one reaction you may well have to your situation is that of asking yourself: How could I be experiencing both these things? How could I possibly be experiencing these things together? And this presupposes, of course, that there is unity or experienced togetherness, even though its existence seems incoherent to you. Moreover, it may be that you can attend to both of your experienced situations all in one glance, as it were. Obviously, you will find your situation as you do so unintelligible, at least until you are able to reason out what must have happened. But this does not establish disunity. For, as we saw in chapter 1, some experiences within a single sense modality have inconsistent or impossible contents.

For clear cases of perceptual-bodily disunity, we must turn, I believe, to actual or possible split-brain scenarios. These are discussed further in chapter 5.