- •I.1 Preliminary Remarks

- •I.2 Cases of Consciousness (or Its Absence)

- •I.3 Kinds of Consciousness

- •I.4 Kinds of Unity

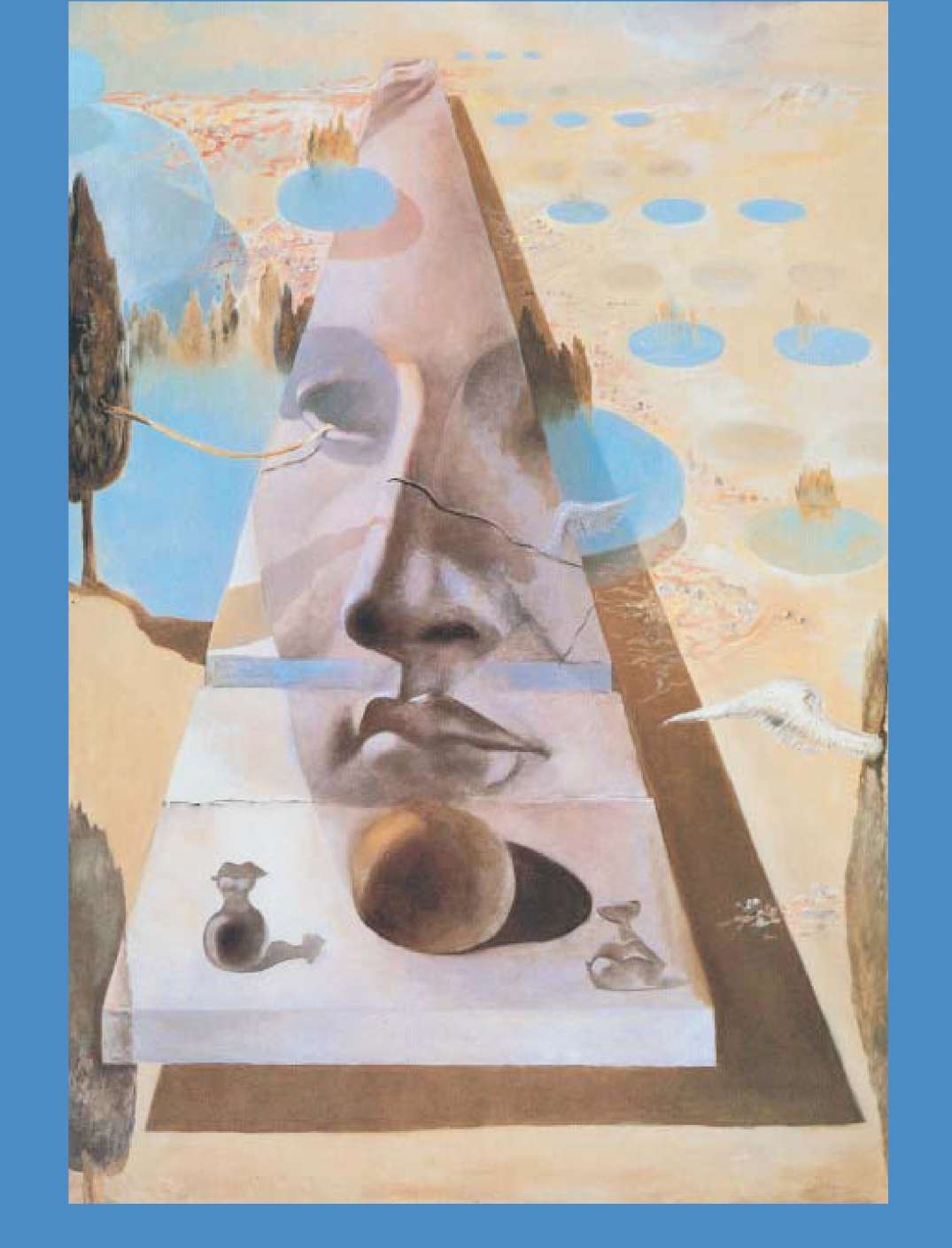

- •Figure I.2

- •1.1 Multiple Experiences and the Problem of Unity

- •1.2 Undermining the Problem as Standardly Conceived

- •1.3 The One Experience View

- •1.4 An Account of Synchronic Phenomenal Unity

- •Figure 1.1

- •2.1 The Body Image

- •2.2 A Theory of Bodily Sensations

- •2.3 The Problem of Bodily Unity

- •3.1 Opening Remarks

- •3.2 Perceptual Consciousness and Experience of the Body

- •3.3 Unity and Conscious Thoughts

- •3.4 Unity and Felt Moods

- •4.1 Examples of Unity through Time

- •4.2 The Specious Present and the Problem of Diachronic Unity

- •4.3 An Account of Unity through Time

- •4.4 Some Mistakes, Historical and Contemporary

- •4.5 Carnap and the Stream of Consciousness

- •5.1 Results of Splitting the Brain

- •Figure 5.1

- •5.2 Multiple Personality Disorder, Split Brains, and Unconscious Automata

- •5.3 Indeterminacy in the Number of Persons

- •5.4 Disunified Access Consciousness

- •5.5 Disunified Phenomenal Consciousness: Two Alternatives

- •5.6 The Nontransitivity of Phenomenal Unity

- •6.1 The Ego Theory and the Bundle Theory Quickly Summarized

- •6.2 Objections to the Ego Theory

- •6.3 Objections to the Bundle Theory

- •6.4 A New Proposal

- •6.5 Problem cases

- •6.6 Vagueness in Personal Identity

- •Introduction

Consciousness and Persons

Unity and Identity Michael Tye

Representation and Mind

Hilary Putnam and Ned Block, editors

Representation and Reality Hilary Putnam

Explaining Behavior: Reasons in a World of Causes Fred Dretske

The Metaphysics of Meaning Jerrold J. Katz

A Theory of Content and Other Essays Jerry A. Fodor

The Realistic Spirit: Wittgenstein, Philosophy, and the Mind Cora Diamond

The Unity of the Self Stephen L. White

The Imagery Debate Michael Tye

A Study of Concepts Christopher Peacocke

The Rediscovery of the Mind John R. Searle

Past, Space, and Self John Campbell

Mental Reality Galen Strawson

Ten Problems of Consciousness: A Representational Theory of the Phenomenal Mind Michael Tye

Representations, Targets, and Attitudes Robert Cummins

Starmaking: Realism, Anti-Realism, and Irrealism Peter J. McCormick (ed.)

A Logical Journey: From Godel to Philosophy Hao Wang

Brainchildren: Essays on Designing Minds Daniel C. Dennett

Realistic Rationalism Jerrold J. Katz

The Paradox of Self-Consciousness Jose Luis Bermudez

In Critical Condition: Polemical Essays on Cognitive Science and the Philosophy of Mind Jerry Fodor

Mind in a Physical World: An Essay on the Mind-Body Problem and Mental Causation Jaegwon Kim

Oratio Obliqua, Oratio Recta: An Essay on Metarepresentation Frangois Recanati

The Mind Doesn't Work That Way Jerry Fodor Consciousness, Color, and Content Michael Tye

New Essays on Semantic Externalism and Self-Knowledge Susana Nuccetelli Consciousness and Persons: Unity and Identity Michael Ty

eUnity and Identity

Michael Tye

A Bradford Book The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, Englan

d© 2003 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Sabon by UG / GGS Information Services, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tye, Michael.

Consciousness and persons: unity and identity / Michael Tye. p. cm.—(Representation and mind) "A Bradford book."

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-20147-X (hc.: alk. paper)

1. Consciousness. 2. Whole and parts (Philosophy). I. Title. II. Series.

B808.9.T935 2003 126—dc21

2002040999

10 98765432

1For Lauretta, Cecily, and Claudia

Contents

Preface xi

Introduction: Kinds of Unity and Kinds of Consciousness 1

Preliminary Remarks 1

Cases of Consciousness (or Its Absence) 2

Kinds of Consciousness 5

Kinds of Unity 11

The Unity of Perceptual Experience at a Time 17

Multiple Experiences and the Problem of Unity 17

Undermining the Problem as Standardly Conceived 21

The One Experience View 25

An Account of Synchronic Phenomenal Unity 36

The Body Image and the Unity of Bodily Experience 43

The Body Image 43

A Theory of Bodily Sensations 49

The Problem of Bodily Unity 62

The Unity of Perceptual and Bodily Experiences, Occurrent Thoughts, and Moods 67

Opening Remarks 67

Perceptual Consciousness and Experience of the Body 68

Unity and Conscious Thoughts 78

Unity and Felt Moods 81

The Unity of Experience through Time 85

Examples of Unity through Time 85

The Specious Present and the Problem of Diachronic Unity 86

An Account of Unity through Time 95

Some Mistakes, Historical and Contemporary 102

Carnap and the Stream of Consciousness 106

Split Brains 109

Results of Splitting the Brain 109

Multiple Personality Disorder, Split Brains, and Unconscious Automata 113

Indeterminacy in the Number of Persons 117

Disunified Access Consciousness 121

Disunified Phenomenal Consciousness: Two Alternatives 126

The Nontransitivity of Phenomenal Unity 129

Persons and Personal Identity 133

The Ego Theory and the Bundle Theory Quickly Summarized 133

Objections to the Ego Theory 134

Objections to the Bundle Theory 138

A New Proposal 140

Problem Cases 143

Vagueness in Personal Identity 15

4Appendix: Representationalism 165 Notes 177 References 187 Index 195

Preface

Some philosophers like to publish large, dense books. I do not. The simple fact is that large philosophy books are rarely read carefully. This is especially true if the books are hard going, as more often than not they are. Philosophers usually take great care in stating their positions; but, in my experience, they have less patience when they read others. I am no different in this regard. My attention span is limited. I don't like having to work hard at trying to understand what the book or article I am reading is saying. I want clarity and, where possible, brevity.

The present book is written for those who share my preferences. Its chapters are divided into numbered sections, typically only a paragraph or two long. The book is clear, I hope, both in structure and content. And it is relatively short. There are even a few cartoons and illustrations to provide some light relief. The issues the book addresses, however, are not light or easy. They have taxed some of the greatest philosophers of the past, and they are slippery and confusing.

This is the third book I have written at least partly on consciousness and it may well be asked how many is enough. I concede that three seems excessive, especially given the veritable explosion of books on consciousness in the last ten years. But excess is not always a bad thing, even if we agree that Oscar Wilde and William Blake went a little over the top when they commented (respectively), "Nothing succeeds like excess" and "The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom." Still, it was an epiphany, rather than a qualified respect for excess, that led to the present work.

The epiphany occurred a couple of years ago, as I was sitting in my garden, having a drink late in the afternoon. (The drink, as I recall, was not alcoholic, as some have supposed.) The air was heavy, there were sounds of birds calling to one another, bees buzzing around nearby flowers, the smell of damp grass, a profusion of colors. What struck me with great intensity was the unity in my experience, the way in which my experience presented all these things to me together. What also struck me was that remarkably this unity hadn't really struck me before, that it was as if I had failed to notice it!

Unity is a fundamental part of our experience, something that is crucial to its phenomenology. It is so fundamental, so much a part of our everyday consciousness, that it is easy to overlook. And this, I speculate, is why more has not been written about it in the recent vigorous debate about phenomenal consciousness. Be that as it may, unity is an important topic that connects both with empirical studies in psychology of people with split brains and with the theoretical, philosophical issue of personal identity.

The book begins with an introduction to the topics of unity and consciousness. Different kinds of unity and consciousness are distinguished, largely to help avoid misunderstanding as to the scope of the theory that follows

.Chapter 1 is concerned to undercut one standard way of thinking about unity for the case of perceptual experience at a single time and to offer an alternative account. Chapter 2 extends this account to the case of bodily sensations at a single time; in the course of so doing, it provides a theory of these sensations. This theory is compatible with my past proposals on bodily sensations (e.g., in Tye 1995a) but it goes beyond them in important ways. Chapter 3 extends the account of unity still further to cover unity for perceptual experiences, bodily sensations, conscious thoughts, and felt moods, again at a single time.

Chapter 4 takes up the knotty issue of the unity of experience through time. Some historical proposals are considered here and a new theory developed. Chapter 5 turns to the case of people whose corpus callosum has been severed, thereby splitting the two hemispheres of the brain. On the basis of the anomalous behavior such individuals exhibit in special experimental settings, they are usually taken to have a divided or disunified consciousness. Sometimes, it is suggested that they are really two persons. An account is proposed and defended of the consciousness of split-brain patients, and it is argued that certain facts about these patients supply further support for the theory of unity on offer.

Finally, in chapter 6, the nature of persons and personal identity is discussed. Some connections are drawn between the issue of identity and that of unity; the discussion also provides further theoretical underpinning for some of the claims about persons in chapter 5. The two great historical theories of the nature of persons—the ego theory and the bundle theory—are found lacking for various reasons, and a new proposal is made. The last part of the chapter takes up the difficult question of whether there can be indeterminacy in personal identity. Here it proves necessary to dangle a toe or two into the quicksand of vagueness; but, given the focus of the book, I resist the temptation to go any deeper.

In my last two books, I laid out and defended the repre- sentationalist view of phenomenal character. That view is directly relevant to the proposals made in this book. However, it is not necessary to endorse the specific theory I take of the phenomenal character of experience in order to find my ideas on unity agreeable. Representationalism is a very general theory. For example, it involves no direct commitment to physicalism and it takes no direct stand on the nature of content. Those who finds themselves attracted to the representationalist view of phenomenal consciousness, even if they are unpersuaded by the specific form of the view I endorse, should still find the current proposals about unity of value. Those who are disinclined to accept even a nonreductive form of representationalism may nonetheless find food for thought in the book; for the simple and appealing way in which representationalism comes to grips with unity provides further reason to take the theory seriously.

Since it may not be fully clear just what the commitments of representationalism are, I have included an appendix on representationalism. This appendix locates my version of representationalism within the space of alternative possible accounts of the theory and it reminds the reader that repre- sentationalism comes in many varieties.

I have given talks on chapters from the book at many places in the United States and the U.K., and I am indebted to a large number of people for helpful comments. I recall in particular remarks by Bob Adams, Kati Balog, Alex Byrne, David Chalmers, Jim Dye, Bob Hale, Shelley Kagan, Sean Kelly, Bob Kuehns, Fiona Macpherson, David Pitt, Joseph Raz, Stephen Read, Mark Sainsbury, Sydney Shoemaker, Susanna Siegel, Charles Spence, Leslie Stevens, Daniel Stoljar, Scott Sturgeon, Jerry Vision, and Crispin Wright. I am also indebted to Jim Gibbs for drawing the cartoons.

The material in the book is new with the exception of part of the introduction, which incorporates (with revisions) some of my "The Burning House," in Conscious Experience (1996), edited by T. Metzinger, and most of section 5 in chapter 6, which draws on my "Vagueness and Reality," Philosophical Topics 28 (2001)

.Introduction: Kinds of Unity and Kinds of Consciousness

I.1 Preliminary Remarks

The thesis that consciousness is necessarily or essentially unified plays a central role in Descartes's writings and also in those of Kant. Descartes took this to have significant implications for whether the mind is a material thing; for, according to Descartes, consciousness is the essence of the mind and any material entity is separable into distinct parts. Kant wisely resisted any such inference. In his view, it is no less puzzling how an immaterial entity without parts could have a unified consciousness than a material entity with parts or components acting together.

Recent work in neuropsychology on subjects whose brains have been bisected seems to undercut the thesis that Descartes and Kant shared. These subjects behave in ways that are often taken to show that their consciousness is disunified. Some contemporary philosophers (Dennett, for example) even hold that consciousness is frequently disunified. What makes the evaluation of claims such as these difficult is that there is no one kind of consciousness and there is no one kind of unity.

I shall not attempt here to draw up an exhaustive list of kinds of consciousness or unity. But it will be useful to distinguish some common kinds, if the main focus of this book is to be properly grasped. I begin by presenting a number of ordinary, everyday cases, in some of which we normally suppose that consciousness is present while in others we deny it. The purpose of these cases is to distinguish between several different kinds of consciousness. The distinctions I draw reflect how we ordinarily think about consciousness. In this way, they are conceptual distinctions.

I.2 Cases of Consciousness (or Its Absence)

Case 1: The Distracted Philosopher

Walking along the road, I find myself lost in thought for several hundred yards, as I make my way home. During this time I manage to keep myself on the sidewalk, but I am not conscious of how things look to me as I walk along. Later on, I "come to" and realize that I have been walking for some time without any real consciousness of my perceptions.1

Case 2: The Bird-watcher

You and I are both bird-watchers. There is a bird singing in a tree nearby. We both hear it, but only you initially are conscious of it by sight. You tell me exactly where to look, and I stare at the right part of the right branch. My retinal image is, let us suppose, just the same as yours when I stand in the spot you are located and look in the same direction. But I report to you that I am not visually conscious of any bird.2

Case 3: The Wine Taster

Apprentice wine tasters are much less discriminating than experts. Through training they come to discriminate flavors that initially seemed to them to be the same. They become conscious of subtle differences in wines of which they were not previously conscious.

Case 4: The Brief Encounter

You are looking at a shelf on which there are eighteen books. Your eyes quickly pass over the entire contents of the shelf. You see more than you consciously notice. Indeed, you see all the books (let us suppose). But you are not conscious of how each of the books looks.

Case 5: The Headache That Won't Go Away

You have a bad headache, which lasts all afternoon. From time to time during the afternoon, there are distractions. You think of other things, you forget for a few moments. In short, you are not always conscious of your headache. When this happens, we do not infer that really you had one headache that ceased at the first distraction, then another quite different headache until the next distraction, so that you were really subject to a sequence of discontinuous headaches.3

Case 6: The Pain in the Night

I am fast asleep. During the night I am awoken by a pain of which, before awakening, I was not conscious.4

Case 7: What It Is Like

I smell a cigar smoldering; I feel a burning pain in my stom- ache; I taste some smoked salmon; I seem to see bright yellow. In each of these cases, I undergo a different feeling or experience. For feelings and perceptual experiences, there is always something it is like to undergo them, some phenomenal or subjective aspects to these mental states. They are inherently conscious mental states.

Case 8: The Boring Shade of Blue

I am staring at a wall that has been painted deep blue. My mind wanders for a few moments, and I am not conscious that I am undergoing a visual experience of blue. But the wall continues to look blue to me even when my mind is wandering.

Case 9: The Party Animal

I am at a party, and I have been drinking all night. Eventually, not long before dawn, I leave. Upon arriving home, I make my weary way to the kitchen and pass out on the kitchen floor. I lose all consciousness.

Case 10: The Dreamer

I am asleep, dreaming that I am being pursued by a pterodactyl that is swooping down on me with evil intent. Even though I am not awake, I am having conscious experiences. These experiences are real to me, so much so that I wake up in a panic.

Case 11: The Sleeping Dog

My dog is asleep. Her eyes are moving rapidly. As they do so, her nose twitches and she growls and shudders. She is having conscious experiences.

Case 12: The "Haunted" Graveyard

One night I take a shortcut home and cross an old graveyard. I suddenly feel very afraid. I seem to smell a strange sweet odor in the air and to see a shape floating over a grave. Although I do not know it, I am hallucinating. I am fully conscious, but the conscious states I am in are delusive.

What are the kinds of consciousness that these cases illustrate?