1schaffner_christina_editor_analysing_political_speeches

.pdf

Page 9

Ohne dies scheinen normale Beziehungen zu der Regierung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland unmöglich zu sein. 8

There is representativeness on both sides. Interestingly, there is asymmetry here. Insulting Gorbachev has been generalised to the 'honour and dignity of a state, of a people'. Should Kohl refuse to set things straight, this will have consequences for the German government (not: the state, or the people).

This example shows that an incumbent of a political function is not in a position to speak casually, at least not in any public situation. The words of the incumbent of the function are not perceived as those of a private person, but in relation to the function and what this function represents.

Footing

The very fact that a speaker represents something means that the speaker fulfils more than one role within his own person. This calls for an analysis of the notion of 'speaker' itself. Erving Goffman, notably in his 1979 paper Footing,9 establishes a framework for the analysis of the different and complicated roles speakers and hearers have within situations of (verbal) communication. For Goffman, the 'speaker' has three roles:

The term 'speaker' is central to any discussion of word production, and yet the term is used in several senses, often simultaneously and (when so) in varying combinations, with no consistency from use to use. One meaning, perhaps the dominant, is that of animator,that is, the sounding box from which utterances come. A second is author,the agent who puts together, composes, or scripts the lines that are uttered. A third is that of principal,the party to whose position, stand, and belief the words attest (Goffman, 1981: 226).10

Levinson (1988: 169) considers Goffman's analysis 'a notable advance on earlier schemes', but not sufficient in three respects:

·even more distinctions are needed for empirical description;

·the definition of the categories is not fully clear;

·it is unclear whether the categories should be related to a single speech act or to an overarching speech-event; Goffman's failure to clarify this relation has as a drawback that different speech events would require different categorisations.11

In order to overcome these insufficiencies, Levinson (1988: 170-4) proposes a more elaborate framework for the analysis of the roles of speaker and hearer in situations of verbal communication. Speaker-related roles ('production roles') may be analysed by asking the four questions as formulated in Table 1.

Each of these four questions may be answered either affirmatively or negatively. Different combinations of affirmative or negative answers yield different roles as related to speech production. For example, an affirmative answer to P4, and negative answers to P1-P3, would yield the role of an absent ghost writer. In normal, spontaneous, dyadic conversation all four questions are answered affirmatively.

In a similar fashion, Levinson offers a framework for the analysis of

Page 10

Table 1 Questions defining production roles (Levinson, 1988: 172)

P1Is the person a direct participant in the situation?

P2Is the person directly involved in the physical transmission of the message?

P3Has the person a motive or desire to communicate the message?

P4Is the person responsible for or involved in devising the form or format of themessage?

Table 2 Questions defining reception roles (Levinson, 1988: 173)

R1Is the person a direct participant in the situation, having a ratified role? R2Is the person directly addressed by the speaker and/or his message? R3Is the person intended to be a/the receiver of the information of the

message?

R4Does the person have immediate access to the channel so as to be able to receive the message directly?

hearer-related roles ('reception roles'). These roles may be characterised by answering the four questions shown in Table 2.

Again, for the hearer in a normal everyday dyadic conversation, all four questions are to be answered affirmatively. In a situation in which Person A asks B to tell Person C something, questions R1, R2 and R4 are affirmative for Person B, whereas question R3 is affirmative for Person C. As Levinson shows, this framework is fruitful for a cross-linguistic and ethnographic analysis of many participant-related phenomena. 12

The questions in Tables 1 and 2 will be the guidelines for the following analysis of representative political speech.

Representative Political Speech

Although some critical linguists might claim that practically any use of language may be considered political in the sense that ideology or world view is involved, I will restrict the term political speech to language use by politicians, i.e. those people who are professionally involved in the management of public affairs. Taken in this sense, the term political speech covers both an enormous quantity and a great multitude of forms, ranging from negotiations and formal meetings, to briefings, press conferences, press interviews, and speeches.

Regardless of whether political language use can be accessed by the public or not, politicians always have to be aware thatas politiciansthey cannot speak casually, as a private person.13 They have to take into account that their utterances must be authorised by their party, that their utterances must be acceptable to their coalition partners, andlast but not leastthat their words must win the favour of the public.14 Any form of political speech is thus geared to being representative of something, and so may be liable to be sanctioned by a higher authority.

However, cases in which this higher authority is the nation itself are rare.15 Political speech that is representative of the nation is rather restricted, in two

Page 11

respects. Firstly, nationally representative speech is restricted to specific persons, or rather, to persons who are the incumbent of specific functions. Representative speeches may be made by a head of state, a prime minister, and the speaker of the parliament, or by persons immediately replacing them. In sum, incumbents of those functions that I have put at the 'fully representative' end of the scale. Other politicians, such as ordinary members of parliament, do not qualify. Secondly, representative speeches are made on specific occasions which must warrant the speech. Examples are memorial services on anniversaries of events of national interest, or state visits in which the relationship between two nations is symbolised in the head of one state paying a visit to the other.

Utterances made on such occasions are interesting because they inevitably show traces of the speaker's search for a representative point of view, acceptable to the nation. 16 Thus, in a speech made at a commemorative event the speaker has to look for the 'national meaning' of such an occasion. The speech counts as a way of establishing that meaning, or reinforcing the sense of that meaning. A comparative analysis of two commemorative speeches made by representatives of the German state (Kopperschmidt, 1989; Ensink, 1995; Sauer, forthcoming) reveals a dramatic difference in the acceptability of the points of view, chosen to be representative. On May 8, 1985, the then German President, Richard von Weizsäcker, commemorated the 40th anniversary of the German capitulation. In his speech he coined the phrase 'May 8 is a day of liberation'. As both Kopperschmidt and Sauer argue, this point of view was as such not novel. The novelty is the declaration of that point of view in a speech by the official representative of Germany, thus ratifying it. This point of view was acceptable to the greater part of the spectrum of German political opinion. It rejects the point of view, according to which Germany was defeated.17 But, at the same time, it presupposes that Germany was a victim of the war rather than an active perpetrator. It thus de-emphasises German guilt and responsibility. On the other hand, Philipp Jenninger, Speaker of the German Parliament, did exactly the opposite in his address on November 9,1988, the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Kristallnacht.Jenninger emphasised German guilt and responsibility. In fact, he chose the question 'what did we Germans do?' as the leading question of his address:

Today we have gathered in the Bundestag in order to commemorate the pogroms of November 9 and 10, 1938. Because we, in the midst of whom the crimes were committed, have to remember and account for them. It is not just for the victims to do so. We Germans should have a clear understanding about our past, and learn from it for the political formation of our present and future. The victims, the Jews all over the world, know only too well what November 1938 was to mean for their future suffering. Do we know as well? (My translation.)

The audience, however, refused to follow Jenninger in his open confrontation with the past. Instead, Jenninger was seen to show too much understanding hence also approvalof what happened during the Third Reich. As a result, his position as Speaker became untenable. Disregarding the question of what is right or wrong about his speech, it appears that Jenninger failed to establish a

Page 12

perspective that was acceptable to his audience. His audience did not feel represented by his words. Most German politicians and political parties distanced themselves from his speech (Ensink, 1992).

In comparison with such commemorative speeches that are essentially addressing one's own nation (both von Weizsäcker and Jenninger spoke at an extraordinary meeting of the national parliament), speeches made in the context of state visits are even more complex. Both the visiting and the hosting nation have perspectives of their own. Apart from these, the relationship between both nations calls for the adoption of a perspective, in which both will feel represented. In our analysis of German President Roman Herzog's address to his Polish hosts (Ensink & Sauer, 1995), we have shown that Herzog primarily takes care of the needs and expectations of his host. He makes an interactional move (asking forgiveness from the Poles) at the culminating point of his speech. Nonetheless, he takes care to represent a broad spectrum of German interests as well, by balancing these needs against those of his hosts.

I will now focus on a speech that was made by a visiting head of state to a parliament of the hosting nation, on the occasion of an official state visit. I will focus on questions of (multiple) representation using an analysis of linguistic phenomena related to footing.

Footing in the Address of Queen Beatrix to the Knesset

On March 27, 28 and 29, 1995, the Dutch Queen Beatrix made a state visit to Israel. This was the very first visit of a Dutch head of state to Israel since its establishment in 1948. In 1993, the Israeli head of state, President Chaim Herzog, had made a state visit to the Netherlands. In general, the relationship between Israel and the Netherlands is considered to be friendly. As part of her state visit, Queen Beatrix was to address the Israeli Parliament, the Knesset. In this paper, I will focus on this address (see Appendix).

According to the Dutch Constitution, the King 18 can do no wrong. The Government ministers are liable for the King's actions. The Netherlands thus has a curtailed kingdom. Beatrix became Queen of the Netherlands in 1980. She is considered a highly professional and serious head of state, supported by both politicians and the Dutch population. Any official action of hers, representative of the Netherlands, must be approved by the government.19

In the weeks before the state visit, a number of Jews, who had previously been resident in the Netherlands and who are now living in Israel, started a campaign in order to correct the favourable image of the Netherlands in Israel, where the Netherlands are considered a friendly and tolerant nation. In accordance with this image, the Dutch were very helpful to the Jews during World War II. In reality, however, 80% of Dutch Jews were transported and killed during the war. Only 20% survived. These figures suggest that many Dutch people collaborated. Hence they demanded that the myth of a people that acted heroically in defence of their Jewish fellow countrymen should be questioned. Members of the Dutch community in Israel wrote letters to President Weizman and Speaker Weiss, in order to plead for such a demystification. On March

27, President Ezer Weizman addressed his Dutch guests at a banquet, drawing attention to the statistics

Page 13

mentioned above. One day later, on March 28, Queen Beatrix gave her address to the Knesset.

In Table 1 and Table 2 I summarised two sets of questions which may serve as a guideline for the analysis. It seems that some of these questions can be answered in a straightforward way. Questions P1 and P2 both pertain to the Queen herself. She isonce she has taken the floorthe one and only speaker. Nevertheless, question P2 is more complex. The Queen's speech is not spontaneous. She is reading an address that has been written. 20 Indeed, the text of what she is saying is already available to journalists under an embargo that may be lifted once the Queen has delivered her address. Hence, there is in fact more than one physical transmission of the message. The official, ratified medium is the Queen speaking, the practical one, in view of the way the media operates, is the written document issued by the Netherlands Information Service.21(I will return to questions P3 and P4 later on.)

This duplication of the transmission of the message has, of course, its complement in the answers to questions R1-R4. (R1) The official audience is the Knesset itself, its members, in the first place its Speaker, who become the persons officially addressed (R2). Furthermore, present among the audience are members of the Israeli government, and guests of honour. Present in a non-official capacity are journalists and media representatives. Although unofficial in terms of the state, these media intermediaries nonetheless play an important role. The officially ratified group is much smaller than all the intended receivers of the Queen's message (R3). Because the state of Israel is a parliamentary democracy, the Knesset is representative of the Israeli nation. Hence, in principle each citizen of Israel belongs, 'through the Knesset', to the intended receivers group. Furthermore, since the Queen speaks in the name of the Netherlands, each citizen of the Netherlands may be considered to have knowledge of the message in which s/he is represented (R4). These groups may only be reached when media intermediaries of press and television will report on and quote from the Queen's message. Their presence allows them to do this job. Or maybe even their presence is wanted in order for them to do this job.

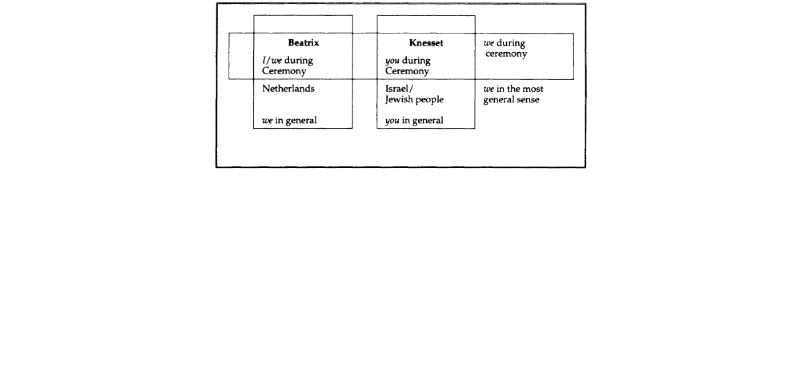

We may represent this state of affairs schematically as in Figure 1, in which one horizontal box intersects two vertical boxes. The horizontal box contains the two ratified parties involved in the communicative event of the delivering of the address, namely, Queen Beatrix as the speaker and members of the Knesset as the audience. The two vertical boxes contain the nations or peoples represented by the two ratified parties, respectively. Thus, the speaker represents the Netherlands, whereas the audience representsin the context of the state visitIsrael. As we will see, Queen Beatrix also considers the Knesset representative of the Jews in general.

As Wortham (1996) has argued, personal pronouns and other deictics are particularly useful for the analysis of footing. Hence, I have indicated the way in which personal pronouns may be used in Queen Beatrix' address in order to refer to any of the three boxes, or combinations thereof.

Let us now turn to the text of the address itself. The address opens with the following paragraph22 which consists of six sentences. In this paragraph, we

Page 14

Figure 1

Reference of personal pronouns

notice several indications of footing according to the analysis summarised in Figure 1 (these are underlined).

Mr. Speaker, Members of the Knesset,

(1) The very name of your parliament, Knesset, takes us back to a distant past. (2) As early as three thousand years ago your forefathers congregated in national assemblies. (3) Though Israel may be relatively young as a state, the Jewish people can look back on a very old history. (4) The traces of those early times are present here in many places and in many forms. (5) Travelling through these biblical lands is therefore like travelling through time. (6) Jerusalem and Jericho, the river Jordanthese old names are in the news even today, but also revive for everyone memories of that long and rich past.

Queen Beatrix starts her address by formally addressing the chairman and the members of the Knesset, thus indicating that they are the ratified audience she is talking to. In (1), she uses both your and us.Both on anaphoric and deictic grounds, your refers to the chairman and members of the Knesset who have just been addressed. It is plausible to consider us an inclusive usage of the pronoun (see Levinson, 1983: 69;although a very general interpretation, including all three boxes of Figure 1, cannot be ruled out). 23 This interpretation fits the horizontal box: the ratified present parties involved in the situation are the point of departure. The formulation distant past also fits in a 'normal' deictic analysis. The past is 'distant' with the 'now' of the Origo as point of reference.

In (2) and (3), the address moves away from the participants in the present ceremony, to what they represent. Your forefathers is still directly linked to the audience. In (3), only descriptive formulations are used: Israel (as a state) and the Jewish people.This sentence is not explicitly coherent with the preceding sentences. Hence, coherence is established implicitly, by invoking inferences.24 One such inference might be, that the 'very old history' the Jewish people can look back on, is symbolised in the forefathers congregating in national assemblies. Another inference is that the Knesset, formally representative of the state of Israel, stands in the tradition of these assemblies, whereas it follows from the juxtaposition of