- •1. Lexicology as a branch of linguistics. Subject matter. Links with other branches. Problems.

- •3. Word as a language unit.

- •4. Meaning. Different approaches to the problem.

- •5. Types of Meaning. The semantic structure.

- •7, Notion and meaning.

- •8, Semantic change. Causes of Semantic Change.

- •10. Polysemy in synchronic approach. Types of meaning.

- •11. Diachronic approach to polysemy.

- •12. Homonymy- Classification of homonyms.

- •16. Synonym. Problem of definition.

- •17. Synonymy in synchronic and diachronic approaches.

- •22. Structural Types of Words, Morphemic structure vs Derivational structure.

- •24. Compounding,

- •26, Minor ways of word-formation.

- •27. Etymological survey of the English vocabulary. Native words vs borrowings.

- •29. Ways of replenishment of the vocabulary.

- •30. Stylistic characteristics of the vocabulary.

- •31. Territorial variants of English in the lexicological aspect.

- •32. Lexicography as a science. Historical background.

11. Diachronic approach to polysemy.

If polysemy is viewed diachronicaily, it is understood as the growth and development of or, in general, as a change in the semantic structure of the word.

Polysemy in diachronic terms implies that a word may retain its previous meaning or meanings and at the same time acquire one or several new ones. Then the problem of the interrelation and interdependence of individual meanings of a polysemantic word may be roughly formulated as follows: did the word always possess alf its meanings or did some of them appear earlier than the others? are the new meanings dependent on the meanings already existing? and if so what is the nature of this dependence? can we observe any changes in the arrangement of the meanings? and so on.

n the course of a diachronic semantic analysis of the polysemantic word table we

5

find that of all the meanings it has in Modern English, the primary meaning is 'a flat slab of stone or wood', which is proper to the word in the Old English period (OE. tabule from L tabula); all other meanings are secondary as they are derived from the primary meaning of the word and appeared later than the primary meaning,

The terms secondary and derived meaning are to a certain extent synonymous. When we describe the meaning of the word as "secondary" we imply that it could not have appeared before the primary meaning was in existence. When we refer to the meaning as "derived'1 we imply not only that, but also that it is dependent on the primary meaning and somehow subordinate to it. In the case of the word table, e.g., we may say that the meaning 'the food put on the table' is a secondary meaning as it is derived from the meaning 'a piece of furniture (on which meals are laid out)\

It follows that the main source of polysemy is a change in the semantic structure of the word.

Polysemy may also arise from homonymy. When two words become identical in sound-form, the meanings of the two words are felt as making up one semantic structure. Thus, the human ear and the ear of corn are from the diachronic point of view two homonyms. One is etymologically related to L aurisP the other to L acus, aceris. Synchronically, however, they are perceived as two meanings of one and the same word. The ear of corn is felt to be a metaphor of the usual type (cf the eye of the needle, the foot of the mountain) and consequently as one of the derived ort synchronical!yr minor meanings of the polysemantic word ear1 Cases of this type are comparatively rare and, as a rule, illustrative of the vagueness of the border-line between polysemy and homonymy.

Semantic changes result as a rule in new meanings being added to the ones already existing in the semantic structure of the word. Some of the old meanings may become obsolete or even disappear, but the bulk of English words tend to an increase in number of meanings.

12. Homonymy- Classification of homonyms.

Homonyms - words identical in their spelling or/and sound form but different in their meaning. When analyzing homonymy, we see that some words are homonyms in all their forms, i.e. we observe full homonymy of the paradigms of two or more different words, e.g., in seali — 'a sea animal1 and seal2 — 'a design printed on paper by means of a stamp: The paradigm "seal, seal's, seals, seals' " is identical for both of them and gives no indication of whether it is seah or seal2, that we are analysing. In other cases, e.g. seah — 'a sea animal' and (to) seal, — 'to close tightly', we see that although some individual word - forms are homonymous, the whole of the paradigm is not identical. It is easily observed that only some of the word-forms (eg, seal, seals, etc.) are homonymous, whereas others (e.g. sealed, sealing) are not. In such cases we cannot speak of homonymous words but only of homonymy of individual word-forms or of partial homonymy This is true of a number of other cases, e.g. compare find [faind], found [faund], found [faund], and found [faund], founded [faundid], founded [faundidj; know [nou], knows [nouz]s knew [nju:], and no [nou]; nose [nouz], noses ['nouzis]; new [nju:] in which partial homonymy is observed. Walter Skeat classified homonyms into: 1) perfect homonyms (they have different meaning, but the same sound form & spelling: school - school); 2) homographs (they have the same spelling: bow /Bay/- bow /боу/}; 3) homophones (same sound form: night- knight),

Smirnitsky classified perfect homonyms into: 1) full homonyms {identical in spelling, sound form, grammatical meaning but different in lexical meaning: spring - spring, springs - springs); 2) homoforms (the same sound form & spelling but different lexical and grammatical meaning: "readings-gerund, particle 1, verbal noun).

6

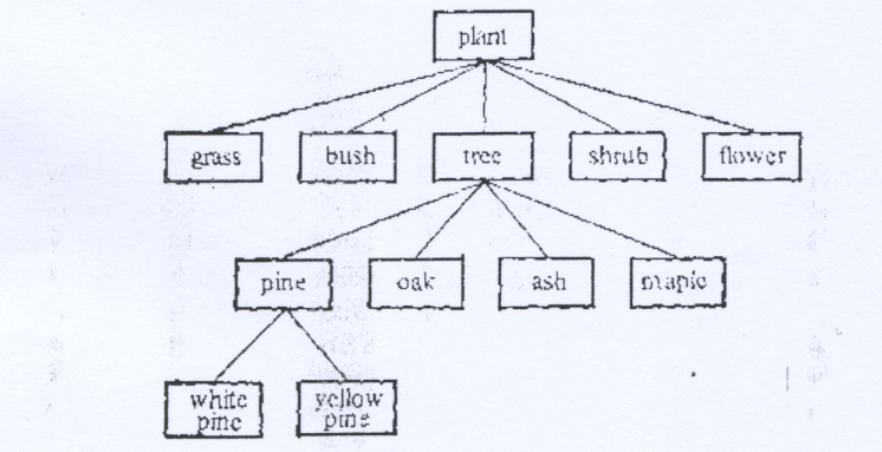

members of which have some features in common, thus distinguishing them from the members of other lexical sub-systems. Words can be classified in various ways. Here, however, we are concerned only with the semantic classification of words. Classification into monosemantic and polysemantic words is based on the number of meanings the word possesses. More detailed semantic classifications are generally based on the semantic similarity (or polarity) of words or their component morphemes. The scope and the degree of similarity (polarity) may be different. Byhyponymy is meant a semantic relationship of inclusion. Thus, e.g., vehicle includes car, bus, taxi and so on; oak implies tree;

horse entails animal; table entails furniture. Thus the hyponymic relationship may be viewed as the hierarchical relationship between the meaning of the general and the individual terms.

The general term (vehicle, tree, animal, etc.) is sometimes referred to as the classifier and serves to describe the lexico-semantic groups, e,g. Lexico-semantic groups (LSG) of vehicles, movement, emotions, etc.

The individual terms can be said to contain (or entail) the meaning of the general term in addition to their individual meanings which distinguish them from each other (cf the classifier move and the members of the group walk, run, saunter, etc.).

It is of importance to note that in such hierarchical structures certain words may be both classifiers and members of the groups. This may be illustrated by the hyponymic structure represented below.

Another way to describe hyponymy is in terms of genus and differentia.

The more specific term is called the h у р о п у т of the more general, and the more general is called the hype го пут or the classifier.

It is noteworthy that the principle of such hierarchical classification is widely used by scientists in various fields of research: botany, geology, etc. Hyponymic classification may be viewed as objectively reflecting the structure of vocabulary and is considered by many linguists as one of the most important principles for the description of meaning.

A general problem with this principle of classification (just as with lexico-semantic group criterion) is that there often exist overlapping classifications. For example, persons may be divided into adults (man, woman, husband, etc.) and children (boy, girl, !adr etc.) but also into national groups (American, Russian, Chinese, etc.)T professional groups (teacher, butcher, baker, etc.), social and economic groups, and so on.

Another problem of great importance for linguists is the dependence of the hierarchical structures cf lexical units not only on the structure of the corresponding group of referents in real world but also on the structure of vocabulary in this or that

8

language.

This can be easily observed when we compare analogous groups in different languages. Thus, e.g., in English we may speak of the lexico-semantic group of meals which includes: breakfast, lunch, dinner, supper,

snack, etc. The word meal is the classifier whereas in Russian we have no word for rneals in general and consequently no classifier though we have several words for different kinds of meals.

Synonyms are words only similar but not identical in meaning. This definition is correct but vague. E, g. horse and animal are also semantically similar but not synonymous. A more precise linguistic definition should be based on a workable notion of the semantic structure of the word and of the complex nature of every separate meaning in a polysemantic word. Each separate lexical meaning of a word has been described in Chapter 3 as consisting of a denotational component identifying the notion or the object and reflecting the essential features of the notion named, shades of meaning reflecting its secondary features, additional connotations resulting from typical contexts in which the word is used, its emotional component and stylistic colouring. Connotations are not necessarily present in every word. The basis of a synonymic opposition is formed by the first of the above named components, i.e. the denotational component. It will be remembered that the term opposition means the relationship of partial difference between two partially similar elements of a language. A common denotational component forms the basis of the opposition in synonymic group. All the other components can vary and thus form the distinctive features of the synonymic oppositions.

Synonyms can therefore be defined in terms of linguistics as two or more words of the same language, belonging to the same part of speech and possessing one or more identical or nearly identical denotational meanings, interchangeable, at least in some contexts without any considerable alteration in denotational meaning, but differing in morphemic composition, phonemic shape, shades of meaning, connotations, style, valency and idiomatic use. Additional characteristics of style, emotional colouring and valency peculiar to one of the elements in a synonymic group may be absent in one or all of the others

Antonyms may be defined as two or mor& words of the same language belonging to the same part of speech and to the same semantic field, identical in style and nearly identical in distribution, associated and often used together so that their denotative meanings render contradictory or contrary notions.